Lumbar Instability: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Liese Bosman (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="noeditbox">Welcome to [[Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project|Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project]]. This space was created by and for the students in the Rehabilitation Sciences and Physiotherapy program of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium. Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!</div> <div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors ''' | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

</div> | |||

== Search Strategy == | |||

add text here related to databases searched, keywords, and search timeline <br> | |||

== Definition/Description == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

add text here | |||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

add text here | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

add text here related to medical diagnostic procedures | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

add links to outcome measures here (also see [[Outcome Measures|Outcome Measures Database]]) | |||

== Examination == | |||

add text here related to physical examination and assessment<br> | |||

== Medical Management <br> == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Physical Therapy Management <br> == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Key Research == | |||

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the [[Template:Case Study|case study template]])<br> | |||

== Resources <br> == | |||

add appropriate resources here <br> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | |||

add text here <br> | |||

== Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | |||

see tutorial on [[Adding PubMed Feed|Adding PubMed Feed]] | |||

<div class="researchbox"> | |||

<rss>Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss> | |||

</div> | |||

== References == | |||

see [[Adding References|adding references tutorial]]. | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project|Template:VUB]] | |||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Anke Jughters|Anke Jughters]] | '''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Anke Jughters|Anke Jughters]] | ||

| Line 8: | Line 82: | ||

• Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed<br>• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ , ‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘ physical mangement lumbar instability’<br> | • Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed<br>• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ , ‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘ physical mangement lumbar instability’<br> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

<u>Segmental instability versus Clinical instability</u><br>Segmental instability is proposed to exist because of failure of the passive restraints (ie, the intervertebral disc, ligaments, and facet joint capsules) that function to limit segment motion <ref name="26">Biely S. et all, Clinical Instability of the Lumbar Spine: Diagnosis and Intervention, Orthopaedic Practice Vol. 18, Level of evidence: 4</ref><br>But the neuromuscular system might also play an important role in controlling segmental motion, a model of a spinal stabilization system was represented by 3 major subsystems. These systems contain the passive subsystem (consisting of vertebrae, facet joints, intervertebral discs, spinal ligaments, joint capsules and passive muscle support), the active subsystem (including the muscles and tendons surrounding the spinal column) and the neural control subsystem (force and motion transducers and the neural control centers). Spinal (lumbar) stability within this model hang on the correct functioning and interaction of all 3 subsystems<ref name="26" />,<ref name="27">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref>. ''(Figure 1)''<br>Segmental instability is defined “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”<ref name="26" />,<ref name="28">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br>The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a neutral zone and an elastic zone ''(Figure 2)''. The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close the neutral position of the segment, a zone in which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic range of motion <ref name="26" />,<ref name="28" />.<br>Segmental instability is considered as an abnormal movement of one vertebra on another secondary due to an increase in the size of the neutral zone.<ref name="26" />,<ref name="28" /><br>Spinal instability is defined as “an abnormal response to applied loads and is characterized by movement of spinal segments beyond the normal constrains” <ref name="1">American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon : A glossary on spinal terminology. Chicage 1985</ref>.<br><br> [[Image:Physiopedia figure 1.png]] [[Image:Physiopedia figure 2.png]] | <u>Segmental instability versus Clinical instability</u><br>Segmental instability is proposed to exist because of failure of the passive restraints (ie, the intervertebral disc, ligaments, and facet joint capsules) that function to limit segment motion <ref name="26">Biely S. et all, Clinical Instability of the Lumbar Spine: Diagnosis and Intervention, Orthopaedic Practice Vol. 18, Level of evidence: 4</ref><br>But the neuromuscular system might also play an important role in controlling segmental motion, a model of a spinal stabilization system was represented by 3 major subsystems. These systems contain the passive subsystem (consisting of vertebrae, facet joints, intervertebral discs, spinal ligaments, joint capsules and passive muscle support), the active subsystem (including the muscles and tendons surrounding the spinal column) and the neural control subsystem (force and motion transducers and the neural control centers). Spinal (lumbar) stability within this model hang on the correct functioning and interaction of all 3 subsystems<ref name="26" />,<ref name="27">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref>. ''(Figure 1)''<br>Segmental instability is defined “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”<ref name="26" />,<ref name="28">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br>The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a neutral zone and an elastic zone ''(Figure 2)''. The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close the neutral position of the segment, a zone in which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic range of motion <ref name="26" />,<ref name="28" />.<br>Segmental instability is considered as an abnormal movement of one vertebra on another secondary due to an increase in the size of the neutral zone.<ref name="26" />,<ref name="28" /><br>Spinal instability is defined as “an abnormal response to applied loads and is characterized by movement of spinal segments beyond the normal constrains” <ref name="1">American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon : A glossary on spinal terminology. Chicage 1985</ref>.<br><br> [[Image:Physiopedia figure 1.png]] [[Image:Physiopedia figure 2.png]] | ||

| Line 88: | Line 162: | ||

== Physical examination == | == Physical examination == | ||

The physical examination may consist of multiple tests :<br>• Low midline sill sign : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the low midline sill sign. The examiner palpates the interspinous space and evaluates the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinosus process.<ref>McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><br>• Interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the interspinous gap change. Then the patient is asked to stand with his or her feet shoulder – width apart , flex their back and place both hands on an examination table. Then the examiner inspects the patient’s back at flexion , focusing on the gaps between interspinous processes. <ref name="34">McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><br>o Flexion : Palpation of the low back at flexion. The examiner palpates individual interspinous spaces of the patient’s back and evaluates the width of individual interspinous spaces and the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinous process. <ref>Kang Ahn et al. New physical examination tests for lumbar spondylolisthesis and instability&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: low midline sill sign and interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion. BMC Muscoluskeletal Disorders, 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B</ref><br>o Extension : Palpation of the low back at extension. The patient is asked to extend his or her upper body and push their buttocks toward the examination table as both hands are on the examination table , which reproduces lumbar extension from the flexion state. The examiner evaluates the interspinous gap change. <ref name="46">Kang Ahn et al. New physical examination tests for lumbar spondylolisthesis and instability : low midline sill sign and interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion. BMC Muscoluskeletal Disorders, 2015. Level of evidence : 2B</ref><br>• Sit – to – stand test : pain immediately on sitting down and relieved by standing up.<ref name="47">Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability : a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence : 2A</ref> | The physical examination may consist of multiple tests :<br>• Low midline sill sign : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the low midline sill sign. The examiner palpates the interspinous space and evaluates the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinosus process.<ref>McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><br>• Interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the interspinous gap change. Then the patient is asked to stand with his or her feet shoulder – width apart , flex their back and place both hands on an examination table. Then the examiner inspects the patient’s back at flexion , focusing on the gaps between interspinous processes. <ref name="34">McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><br>o Flexion : Palpation of the low back at flexion. The examiner palpates individual interspinous spaces of the patient’s back and evaluates the width of individual interspinous spaces and the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinous process. <ref>Kang Ahn et al. New physical examination tests for lumbar spondylolisthesis and instability&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: low midline sill sign and interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion. BMC Muscoluskeletal Disorders, 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B</ref><br>o Extension : Palpation of the low back at extension. The patient is asked to extend his or her upper body and push their buttocks toward the examination table as both hands are on the examination table , which reproduces lumbar extension from the flexion state. The examiner evaluates the interspinous gap change. <ref name="46">Kang Ahn et al. New physical examination tests for lumbar spondylolisthesis and instability : low midline sill sign and interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion. BMC Muscoluskeletal Disorders, 2015. Level of evidence : 2B</ref><br>• Sit – to – stand test : pain immediately on sitting down and relieved by standing up.<ref name="47">Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability : a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence : 2A</ref> | ||

• Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movements ( = PAIVM ) : the intervertebral motion was tested with the patient prone. The examiner contacted the spinous process with the hypothenar eminence and produces a posterior – to – anterior force. Each segment was judged as normal mobility , hypermobility or hypomobility. Pain was writtes as present or absent.<ref name="47" /><br>• Posterior shear test : the patient is standing with his hands across the lower abdomen. The examiner place one hand over the patient’s crossed arms. The other hand was placed on the patient’s pelvis ( stabilisation ). There is a posterior shear force produced by the examiner through the patient’s abdomen. An anteriorly stabilizing force was produced with the other hand. The examiner repeats the test at each lumbar level by changing the point of contact of the posterior hand. The test is positive if familiar symptoms were provoked. <ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_pelvic_pain_provocation_test www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_pelvic_pain_provocation_test]<br>• Prone instability test : The test is performed with the patient prone , with the trunk supported on the table and with the feet on the floor. Then the examiner performed a PAIVM test to each level of the lumbar spine. Any provocation of pain was recorded. Then the examiner repeats the test but now with the patient’s feet off the floor. The test was postive when pain was present in the resting position but subsided in the second position. <ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test]<br>• Beighton hypermobility scale : Ligamentous laxity measured with a 9-point Beighton scale. One point was given for each of the following aspects : knee hyperextension greater than 10° , elbow hyperextension greater than 10° , fifth finger hyperextension greater than 90° , thumb abduction to contact the forearm , and ability to flex the trunk and place hands flat on the floor with knees extended.<ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score]<br>• Passive Physiological Intervertebral Motion ( = PPIVM ) : the patient sidelies. The test consisted of moving the patient’s spine through sagittal forward – bending ( flexion ) and backward – bending ( extension ) , using the lower extremities. Meanwhile the examiner palpates between the spinous process of the adjacent vertebrae to assess the motion taking place at each motion segment. <ref name="47" /><br>• Passive Lumbar Extension ( = PLE test ) : the patient is in prone position. Then both lower extremities were elevated ( passive ) to a height of about 30cm. The knees maintain extended and the examiner gently pulls the legs of the patient. <ref name="47" /><br>• Instability catch sign : the patient bend his or her body forward as much as possible and then return to the neutral position. The test is positive when the patient isn’t able to return to the neutral position. <ref name="47" /> | • Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movements ( = PAIVM ) : the intervertebral motion was tested with the patient prone. The examiner contacted the spinous process with the hypothenar eminence and produces a posterior – to – anterior force. Each segment was judged as normal mobility , hypermobility or hypomobility. Pain was writtes as present or absent.<ref name="47" /><br>• Posterior shear test : the patient is standing with his hands across the lower abdomen. The examiner place one hand over the patient’s crossed arms. The other hand was placed on the patient’s pelvis ( stabilisation ). There is a posterior shear force produced by the examiner through the patient’s abdomen. An anteriorly stabilizing force was produced with the other hand. The examiner repeats the test at each lumbar level by changing the point of contact of the posterior hand. The test is positive if familiar symptoms were provoked. <ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_pelvic_pain_provocation_test www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_pelvic_pain_provocation_test]<br>• Prone instability test : The test is performed with the patient prone , with the trunk supported on the table and with the feet on the floor. Then the examiner performed a PAIVM test to each level of the lumbar spine. Any provocation of pain was recorded. Then the examiner repeats the test but now with the patient’s feet off the floor. The test was postive when pain was present in the resting position but subsided in the second position. <ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test]<br>• Beighton hypermobility scale : Ligamentous laxity measured with a 9-point Beighton scale. One point was given for each of the following aspects : knee hyperextension greater than 10° , elbow hyperextension greater than 10° , fifth finger hyperextension greater than 90° , thumb abduction to contact the forearm , and ability to flex the trunk and place hands flat on the floor with knees extended.<ref name="47" /><br>[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score]<br>• Passive Physiological Intervertebral Motion ( = PPIVM ) : the patient sidelies. The test consisted of moving the patient’s spine through sagittal forward – bending ( flexion ) and backward – bending ( extension ) , using the lower extremities. Meanwhile the examiner palpates between the spinous process of the adjacent vertebrae to assess the motion taking place at each motion segment. <ref name="47" /><br>• Passive Lumbar Extension ( = PLE test ) : the patient is in prone position. Then both lower extremities were elevated ( passive ) to a height of about 30cm. The knees maintain extended and the examiner gently pulls the legs of the patient. <ref name="47" /><br>• Instability catch sign : the patient bend his or her body forward as much as possible and then return to the neutral position. The test is positive when the patient isn’t able to return to the neutral position. <ref name="47" /> | ||

| Line 100: | Line 174: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.<br>In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)<br>The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test ) was found to have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity , as well as the highest LR+. The PLE test has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2. <ref>Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref name="57">Silvano Ferarri et al., A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr Man Therap., April 2015; 23:14. Level of evidene: 2A</ref><sup></sup><br> | In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.<br>In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)<br>The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test ) was found to have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity , as well as the highest LR+. The PLE test has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2. <ref>Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref name="57">Silvano Ferarri et al., A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr Man Therap., April 2015; 23:14. Level of evidene: 2A</ref><sup></sup><br> | ||

== Medical Management <br> == | == Medical Management <br> == | ||

| Line 138: | Line 212: | ||

On Physiopedia : [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School] <br>There moderate evidence suggested that back schools have better short- and intermediate-term effects on the functional status and pain than other treatments for patients with recurrent and chronic low back pain (LBP) Moderate evidence suggests that a back school for chronic LBP in an occupational setting are even more effective than the other treatments. | On Physiopedia : [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School] <br>There moderate evidence suggested that back schools have better short- and intermediate-term effects on the functional status and pain than other treatments for patients with recurrent and chronic low back pain (LBP) Moderate evidence suggests that a back school for chronic LBP in an occupational setting are even more effective than the other treatments. | ||

Acupuncture, back schools, behavioural therapy, and spinal manipulation may reduce pain in the short term, but effects on function are unclear. In this systematic review,they don't know whether back schools are more effective than placebo gel, waiting list, no intervention, or written information at reducing pain ( low-quality evidence ). Compared with other treatments: They don't know whether back schools are more effective than spinal manipulation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physiotherapy, callisthenics, or exercise at reducing pain (low-quality evidence). <sup>[</sup><ref name="59">Roger Chou.Low back pain (chronic). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><sup>, Level of evidence: 1A]</sup><br><br> | Acupuncture, back schools, behavioural therapy, and spinal manipulation may reduce pain in the short term, but effects on function are unclear. In this systematic review,they don't know whether back schools are more effective than placebo gel, waiting list, no intervention, or written information at reducing pain ( low-quality evidence ). Compared with other treatments: They don't know whether back schools are more effective than spinal manipulation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physiotherapy, callisthenics, or exercise at reducing pain (low-quality evidence). <sup>[</sup><ref name="59">Roger Chou.Low back pain (chronic). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010. Level of evidence: 1A</ref><sup>, Level of evidence: 1A]</sup><br><br> | ||

== Key Research == | == Key Research == | ||

Revision as of 17:49, 4 October 2016

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Sam Van de Mosselaer, Tessa de Jongh, Anke Jughters, Andeela Hafeez, Admin, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kai A. Sigel, Rachael Lowe, Elien Clerix, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Tony Varela, Liese Bosman, Vandoorne Ben, Shaimaa Eldib, Tony Lowe, Elaine Lonnemann, Robert Pierce and Mats Vandervelde

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

add text here related to databases searched, keywords, and search timeline

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

add text here

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

add text here

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

add text here

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

add text here

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

add text here related to medical diagnostic procedures

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Examination[edit | edit source]

add text here related to physical examination and assessment

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

add text here

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

Original Editors - Anke Jughters

Top Contributors - Sam Van de Mosselaer, Tessa de Jongh, Anke Jughters, Andeela Hafeez, Admin, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kai A. Sigel, Rachael Lowe, Elien Clerix, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Tony Varela, Liese Bosman, Vandoorne Ben, Shaimaa Eldib, Tony Lowe, Elaine Lonnemann, Robert Pierce and Mats Vandervelde

Search strategy[edit | edit source]

• Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed

• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ , ‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘ physical mangement lumbar instability’

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Segmental instability versus Clinical instability

Segmental instability is proposed to exist because of failure of the passive restraints (ie, the intervertebral disc, ligaments, and facet joint capsules) that function to limit segment motion Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

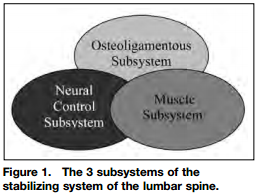

But the neuromuscular system might also play an important role in controlling segmental motion, a model of a spinal stabilization system was represented by 3 major subsystems. These systems contain the passive subsystem (consisting of vertebrae, facet joints, intervertebral discs, spinal ligaments, joint capsules and passive muscle support), the active subsystem (including the muscles and tendons surrounding the spinal column) and the neural control subsystem (force and motion transducers and the neural control centers). Spinal (lumbar) stability within this model hang on the correct functioning and interaction of all 3 subsystemsCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title. (Figure 1)

Segmental instability is defined “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

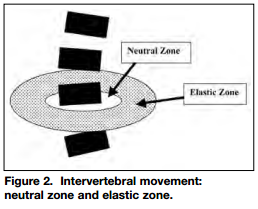

The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a neutral zone and an elastic zone (Figure 2). The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close the neutral position of the segment, a zone in which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic range of motion Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title.

Segmental instability is considered as an abnormal movement of one vertebra on another secondary due to an increase in the size of the neutral zone.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Spinal instability is defined as “an abnormal response to applied loads and is characterized by movement of spinal segments beyond the normal constrains” Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine exists of five moveble vertebrae, called by L1 to L5 (Five moveable vertebrae (L1-L5) realize the lumbar spine.) These strong vertebrae are linked by multiple bony elements connected by joints capsules, flexible ligaments/tendens, large muscles, and high sensitive nerves.

The lumbar spine is intended to be very strong, so it can protect the sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. But, it’s also highly flexible for mobility of the back (flexion, extension, side bending and rotation). Having regard to the form of the joints in the lumbar region, flexion and extension the main motion directions. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

For more detailed anatomy:

[[The lumbar spine exists of five moveble vertebrae, called by L1 to L5 (Five moveable vertebrae (L1-L5) realize the lumbar spine.) These strong vertebrae are linked by multiple bony elements connected by joints capsules, flexible ligaments/tendens, large muscles, and high sensitive nerves. The lumbar spine is intended to be very strong, so it can protect the sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. But, it’s also highly flexible for mobility of the back (flexion, extension, side bending and rotation). Having regard to the form of the joints in the lumbar region, flexion and extension the main motion directions. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

For more detailed anatomy:

www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain_and_Pelvic_Floor_Disorders

Epidemiology /Etiology

[edit | edit source]

The etiology of intervertebral disk degeneration is largely unknown, but it is thought that disk nutrition is involved (49,50). The normal intervertebral disk is avascular and receives its nutrition by passive diffusion from vessels in the endplate and around the annulus. In man, the relative contributions are unknown, but the importance of the vascular channels in the endplate has been stressed.[1][2]

Lumbar spinal instability may be caused by:

• degenerative disease

• postoperative status

• trauma to spine or its surrounding structures

• development disorders, like scoliosis and other congenital spine lesions

• infection

• tumors Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Also poor lifting technique such as forward-bend posture and asymmetric lifting is associated with Low Back Pain. A constant morphological modification of the spine alters the biomechanical loading from back muscles, ligaments, and joints, and can harvest back injuries.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleGranata et all., described that body mass, task asymmetry, and level of experience affected the scale and variability of spinal load during repeated lifting efforts.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title In older people, bending and lifting activities produce loads on the spine that exceed the failure of vertebrae with low bone mineral density, which is linked with spinal degeneration. The degenerative transformation has influence on the intervertebral discs, ligament and bone.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

There is a 50–70% chance of a person having LBP pain during his or her lifetime, with a prevalence of about 18%. Specific causes for most LBP are not known. Although negative social interaction (for example, dissatisfaction at work) has been found to relate to chronic LBP, a significant portion of the prob-lem is of mechanical origin. It is often referred to as clinical spinal instability. There have been several similar studies over the past 50 years, but the results have been unclear. In association with back or neck pain, some investigators found increased motion[3][4], whereas others found decreased motion . Some reasons for the uncertainties have been the varia-bility in the voluntary efforts of the subjects to produce spinal motion, the presence of muscle spasm and pain during the radiographic examination, lack of appropriate control subjects matched in age and gender, and the lim-ited accuracy of in vivo methods for measuring motion.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Commonly a history of lower back pain, which may or may not be accompanied by sciatica (with or without neurological signs).

Lumbar pain is often relived by rest or by waring a support, but may recur with a small amount of movement, such as a twist or sprain.

Pain made worse by maintaining one posture for a long period of time (standing or sitting).

Pain is usually relieved by mobilisation or manipulation, often with complete resolution of leg pain and neurological symptoms. However, relief is temporary, giving way to recurring pain a few days later with no obvious triggers.

In some patients, a steadily increasing lumbosacral ache when extremes of spinal movement are sustained for more then 15 seconds

Some patients may also report a painful arc with lumbar flexion or coming out of flexion.

In some cases, lumbar instability may cause a ‘catch’ in the back or even a ‘locking’ sensation.[5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

• Intervertebral disc prolapse

• Muscle injury Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Muscle_Injuries

• Muscle strain Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Muscle_Strain

• Ligamentous overload

• Postural overstretching

• Spondylosis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spondylosis

• Arthrosis of the spinal joints

• Lumbar spine fracture

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spine_Fracture

• Kidney problem

• Spondylolisthesis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Spondylolisthesis

• Hypermobility syndrome

www.physio-pedia.com/Hypermobility_Syndrome

• Spinal tumor Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Dysfunction

• Osteoporosis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoporosis

• Sciatica Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Sciatica

• Degenerative disc disease Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Degenerative_Disc_Disease

• Rheumatoid arthritis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Rheumatoid_Arthritis

• Urinary tract infection Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Nephrolithiasis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Nephrolithiasis_(Kidney_Stones)

• Abdominal aortic aneurysm

• Referred visceral dysfunctions

• Lumbar degenerative joint disease

• Lumbar compression fracture

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_compression_fracture

• Lumbar facet arthropathy

• Abnormalities of the lumbar nerve roots

• Degenerative synovial cysts

• Extraspinal causes

• Infection

• Inflammatory conditions

• Metastic neoplasms

• Connective tissue disease

• Metabolic disease

• Myelitis Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Seronegative arthritic diseases

Diagnostic Procedure[edit | edit source]

→ neutral radiography:

Shows many indirect signs that are associated with spinal instability:

1. Moderate disc degeneration with mild space narrowing, osteosclerosis and osteophytosis of the vertebral end plates [6]

2. Presence of traction spur, which is a particular type of osteophyte that is located 2-3 mm from the end plate and has a horizontal orientation. [7]

3. Intervertebral vacuum phenomenon is due to rupture of the insertion of Sharpey’s fibres and may be the result of vertebral instability [8]

→ functional radiography

This is the perfect method to show intervertebral instability or abnormal motion between two vertebrae. Dynamic radiographs obtained in both flexion and extension, prove to be a simple and reliable method to determine motion segment instability and can also indicate the lesions located in specific areas based on the ‘‘dominant lesion’’ concept [9]

→ computed tomography

This technique is aimed at demonstrating a gap in the facet joints during rotation of the trunk, which is an indirect sign of spinal instability.

→ magnetic resonance imaging

MRI claimed to be the best method to find lumbar instability. However, symptoms may not always be defined to morphological lesions such as disc herniation, foraminal stenosis or stenosis of the spinal canal but rather to segmental instability [10]. Identifying patients with an increased chance of instability on MR imaging can be clinically relevant and can influence indications for functional radiographs.

Outcome Measures

[edit | edit source]

- Oswestry Disability Index: subjective percentage score of level of function (disability) in activities of daily living in those rehabilitating from low back pain.

Minimal detectable chance is 5-6 points and the minimum clinically important difference is 6 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Scores from 0% to 20% indicate minimal disability

20% to 40%, moderate disability

40% to 60%, severe disability;

60% to 80%, crippled

80% to 100%, bedbound or exaggerating Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Oswestry_Disability_Index

- Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: the Quebec back pain disability scale (QBPDS) is a condition-specific questionnaire developed to measure the level of functional disability for patients with low back pain.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The end score will be between 0 (no limitation) and 100 (totally limited).

The minimum clinically important difference is 15 points when suffering acute low back pain of chronic low back pain.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Quebec_Back_Pain_Disability_Scale

- Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire: This questionnaire is designed to assess self-rated physical disability caused by low back pain.

o When the score at intake is < 9 points; Minimal detectable change (MDC) = 6,7 points and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is 2-3 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

o When the score at intake is between 9-16: MDC = 4-5 points and MCID = 5-9 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

o When the score at intake is > 16 points: MDC = 8,6 points and MCID = 8-13 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

MIC absolute cutoff, minimal important change = 5 points for patients with low back pain. MIC (% imporovement from baseline) = 30%Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Roland%E2%80%90Morris_Disability_Questionnaire

- Patient Specific Functional Scale: This useful questionnaire can be used to quantify activity limitation and measure functional outcome for patients with any orthopaedic condition.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The Minimal detectable change (MDC) is for chronic pain = 2 points, for low back pain = 1,4 points and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID)= 2,0 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Stratford et alCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title found the average of the MCID scores for 3 activities to be 0.8 (“small change”), 3.2 (“medium change”), and 4.3 (“large change”) PSFS points in patients with chronic low back pain.

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination may consist of multiple tests :

• Low midline sill sign : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the low midline sill sign. The examiner palpates the interspinous space and evaluates the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinosus process.[11]

• Interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion : first there is an inspection of the low back to detect the interspinous gap change. Then the patient is asked to stand with his or her feet shoulder – width apart , flex their back and place both hands on an examination table. Then the examiner inspects the patient’s back at flexion , focusing on the gaps between interspinous processes. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

o Flexion : Palpation of the low back at flexion. The examiner palpates individual interspinous spaces of the patient’s back and evaluates the width of individual interspinous spaces and the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinous process. [12]

o Extension : Palpation of the low back at extension. The patient is asked to extend his or her upper body and push their buttocks toward the examination table as both hands are on the examination table , which reproduces lumbar extension from the flexion state. The examiner evaluates the interspinous gap change. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Sit – to – stand test : pain immediately on sitting down and relieved by standing up.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movements ( = PAIVM ) : the intervertebral motion was tested with the patient prone. The examiner contacted the spinous process with the hypothenar eminence and produces a posterior – to – anterior force. Each segment was judged as normal mobility , hypermobility or hypomobility. Pain was writtes as present or absent.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Posterior shear test : the patient is standing with his hands across the lower abdomen. The examiner place one hand over the patient’s crossed arms. The other hand was placed on the patient’s pelvis ( stabilisation ). There is a posterior shear force produced by the examiner through the patient’s abdomen. An anteriorly stabilizing force was produced with the other hand. The examiner repeats the test at each lumbar level by changing the point of contact of the posterior hand. The test is positive if familiar symptoms were provoked. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Posterior_pelvic_pain_provocation_test

• Prone instability test : The test is performed with the patient prone , with the trunk supported on the table and with the feet on the floor. Then the examiner performed a PAIVM test to each level of the lumbar spine. Any provocation of pain was recorded. Then the examiner repeats the test but now with the patient’s feet off the floor. The test was postive when pain was present in the resting position but subsided in the second position. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test

• Beighton hypermobility scale : Ligamentous laxity measured with a 9-point Beighton scale. One point was given for each of the following aspects : knee hyperextension greater than 10° , elbow hyperextension greater than 10° , fifth finger hyperextension greater than 90° , thumb abduction to contact the forearm , and ability to flex the trunk and place hands flat on the floor with knees extended.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score

• Passive Physiological Intervertebral Motion ( = PPIVM ) : the patient sidelies. The test consisted of moving the patient’s spine through sagittal forward – bending ( flexion ) and backward – bending ( extension ) , using the lower extremities. Meanwhile the examiner palpates between the spinous process of the adjacent vertebrae to assess the motion taking place at each motion segment. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Passive Lumbar Extension ( = PLE test ) : the patient is in prone position. Then both lower extremities were elevated ( passive ) to a height of about 30cm. The knees maintain extended and the examiner gently pulls the legs of the patient. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Instability catch sign : the patient bend his or her body forward as much as possible and then return to the neutral position. The test is positive when the patient isn’t able to return to the neutral position. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Painful catch sign : the patient is in supine position and then the examiner asks the patient to lift both lower extremities. The knees must be extended. Then the examiner asks the patient to return slowly to the begin positon. If the lower extremities fell down instantly because of the low back pain , the test was positive. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

• Apprehension sign : The examiner asks the patient if he or she has a sensation of lumbar collapse because of the low back pain while performing ordinary acts like bending back and forward , bending from side to side , sitting down or standig up. The test was positive if the patient had a sensation of lumbar collapse. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleThe condition has a unique clinical presentation that displays its symptoms and movement dysfunction within the neutral zone of the motion segment. The loosening of the motion segment secondary to injury and associated dysfunction of the local muscle system renders it biomechanically vulnerable in the neutral zone. The clinical diagnosis of this chronic low back pain condition is based on the report of pain and the observation of movement dysfunction within the neutral zone and the associated finding of excessive intervertebral motion at the symptomatic level. Four different clinical patterns are described based on the directional nature of the injury and the manifestation of the patient's symptoms and motor dysfunction. A specific stabilizing exercise intervention based on a motor learning model is proposed and evidence for the efficacy of the approach provided.[13],[14]

• The PLE is the most informative clinical test: sensitivity (0.84, 95% CI: 0.69 - 0.91) and high specificity (0.90, 95% CI: 0.85 -0.97).

• The diagnostic accuracy of AMP depends on each singular test.

• The PIT and the PST have a moderate sensitivity and specificity:

o PIT sensitivity = 0.71 (95% CI: 0.51 - 0.83), specificity = 0.57 (95% CI: 039 - 0.78);

o PST sensitivity = 0.50 (95% CI: 0.41 - 0.76), specificity = 0.48 (95% CI: 0.22 - 0.58).

The PLE showed a good reliability (k = 0.76), but needs more invesagation because this is the result of one study.

The inter-rater reliability of the PIT ranged by slight (k = 0.10 and 0.04), to good (k = 0.87).

The inter-rater reliability of the AMP ranged by slight (k = −0.07) to moderate (k = 0.64), whereas the inter-rater reliability of the PST was fair (k = 0.27). [15]

In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.

In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)

The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test ) was found to have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity , as well as the highest LR+. The PLE test has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2. [16],[17],Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Lumbar segmental instability is considered to represent a significant sub-group within the chronic low back pain population. In chronic overt instability and covert instability, medical treatment plays a more prominent role. If not at risk for imminent neurological deterioration, the patients with these forms of instability generally undergo conservative (nonsurgical) treatment first. Fusion is reserved for those in whom conservative treatment fails.

medication:Analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants, tricyclic antidepressants, anti-epileptics.

Surgerical management[edit | edit source]

Once the decision has been made to fuse a particular spine segment, there may be several surgical methods to accomplish this task. After a particular method is selected, the etiology of instability is no longer relevant, as the technical steps would be the same.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Posterior and posterolateral noninstrumented lumbar fusion The lumbar spine is exposed in standard fashion through a posterior midline incision. Bilateral exposure of the laminae is extended further laterally to completely expose of the facet joints and transverse processes of the vertebrae to be fused. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Instrumented lumbar fusion with pedicle screws

The spine is exposed (and decompressed if necessary) as for a noninstrumented fusion. Pedicle screws are inserted into the pedicles above and below the motion segment to be fused. The main concern during pedicle screw insertion is to avoid breach of the pedicle wall and injury to the exiting nerve root. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The indications for spinal fusion in the treatment of degenerative instability are controversial. The basic problem lies, as discussed earlier, in the definition and the diagnosis of the disorder. However, despite the fact that indications for the procedure are uncertain, that costs and complication rates are higher than for other surgical procedures performed on the spine, and that long-term outcomes are uncertain, the rate of lumbar spinal fusion is increasing rapidly in the United States.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title The rate of back surgery and especially of spinal fusion operations is at least 40% higher in the US than in any other country and is five times higher than in the UK.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Although there have been no randomized trials evaluating the effectiveness of lumbar fusion for spinal instability, the feeling remains that the operation should be reserved for patients with severe symptoms and radiographic evidence of excessive motion (greater than 5 mm translation or 10° of rotation) who fail to respond to a trial of non-surgical treatment.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title The latter should consist of a combination of patient education, physical training and sclerosing injections.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Patient education may be important in the treatment of patients with segmental instability. Education should, first of all, focus on preventing loaded flexion movements, as they may create a posterior shift of the disc. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1A] End-range positions of the lumbar spine should also be avoided because these overload the posterior passive stabilizing structures. Physical therapy for segmental instability focuses on exercises designed to improve stability of the spine. As the lumbar erector spinae muscles are the primary source of extension torque for lifting tasks, strengthening of this muscle group has been supported.[Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 1B ]Intensive dynamic exercises for the extensors proved to be significantly superior to a regime of standard treatment of thermotherapy, massage and mild exercises in patients with recurrent LBP.[Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B]The abdominal muscles, particularly the transversus abdominis and oblique abdominals, have also been proposed as having an important role in stabilizing the spine by co-contracting in anticipation of a tested load. However, exercises proposed to address the abdominal muscles in an isolated manner usually involve some type of sit-up manœuvre that imposes dangerously high compressive and shear forces on the lumbar spine [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ] and may provoke a posterior shift of the (unstable) disc (see figure 3). Alternative techniques should therefore be tested when training these muscles. Some authors strongly suggest that the transversus abdominis [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 2A ] and the multifidus muscles make a specific contribution to the stability of the lower spine [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 2B ] [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2A ] and an exercise programme that proposes the retraining of the co-contraction pattern of the transversus abdominis and multifidus muscles has been described. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1C ]The exercise programme is based on training the patient to draw in the abdominal wall while isometrically contracting the multifidus muscle, and consists of three different levels:

• First, specific localized stabilization training is given. Lying prone, sitting and standing upright, the patient performs the isometric abdominal drawing-in manœuvre with co-contraction of the lumbar multifidus muscles. = Segmental control over primary stabilizers (mainly TrA, deep multifidus, pelvic floor and diaphragm) [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 5 ]

• During the phase of general trunk stabilization, the co-contraction of the same muscles is carried out on all fours, and then elevating one arm forwards and/or the contralateral leg backwards, or on standing upright and elevating one arm forwards and/or bringing the contralateral leg backwards. = Exercises in closed chain, with low velocity and low load [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ]

• Third, there is the stabilization training. Once accurate activation of the co-contraction pattern is achieved, training is given in functional movements, such as standing up from a sitting or lying position, bending forwards and backwards and turning. All daily activities are then integrated. A significant result from a randomized trial has recently been reported comparing this exercise programme with one of general exercise (swimming, walking, gymnastic exercises) in a group of patients with chronic LBP.[Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B ]= Exercises in open chain, with high velocity and load [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ]

Despite the positive results with muscular training programmes, it remains difficult to understand how training of the lumbar and abdominal muscles can improve segmental stability. Not only do the muscles (except for multifidus) have multisegmental attachments to the lumbar vertebrae, but also they are not very well oriented to resist displacements. Because they mainly run longitudinally, they can only resist sagittal rotation and are not able to resist anterior or posterior shears. However, whenever the muscles contract, and especially when they do this simultaneously, they exert a compressive load on the whole lumbar spine, as well as on the unstable segment. By compressing the joints, the muscles make it harder for the joints and for the intradiscal content to move. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2B ] The most important contribution of trained muscles to spinal stability may therefore be the creation of a rigid cylinder around the spine and increased stiffness. It is important, however, for exercises to be prescribed as a means of prevention only after the actual problem – usually a discodural interaction – has been solved by manipulation, mobilization, traction or passive postural exercises.[Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2A ]

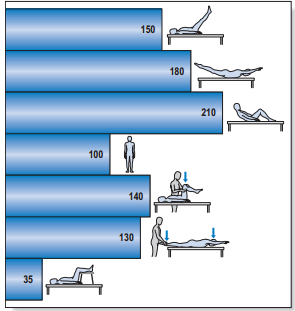

Figure 3: Intradiscal pressure in % of that of the standing position

For excercises : www.physio-pedia.com/Exercises_for_Lumbar_Instability

The effectivity of back school program has been shown and is more effective than any educational intervention in general health status and in decreasing acetaminophen and NSAID intake. It was ineffective in the other quality of life domains, in pain, functional status, anxiety and depression. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B ]

Other RCT of the effectivity of back school: Sahin N, Albayrak I, Durmus B, Ugurlu H.. Effectiveness of back school for treatment of pain and functional disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2011 Feb;43(3):224-9.

In this RCT was the addition of back school more effective than exercise and physical treatment modalities alone in the treatment of patients with chronic low back pain. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence: 1B]

On Physiopedia : http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School

There moderate evidence suggested that back schools have better short- and intermediate-term effects on the functional status and pain than other treatments for patients with recurrent and chronic low back pain (LBP) Moderate evidence suggests that a back school for chronic LBP in an occupational setting are even more effective than the other treatments.

Acupuncture, back schools, behavioural therapy, and spinal manipulation may reduce pain in the short term, but effects on function are unclear. In this systematic review,they don't know whether back schools are more effective than placebo gel, waiting list, no intervention, or written information at reducing pain ( low-quality evidence ). Compared with other treatments: They don't know whether back schools are more effective than spinal manipulation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physiotherapy, callisthenics, or exercise at reducing pain (low-quality evidence). [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, Level of evidence: 1A]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

• McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A

• Callaghan JP, Gunning JL, McGill SM. The relationship between lumbar spine load and muscle activity during extensor exercises. Phys Ther 1998;78:8–18. Level of evidence: 1B

• Manniche C, Hesselsoe G, Bentzen L, et al. Clinical trial of intensive muscle training for chronic low back pain. Lancet 1988;24– 31;2(8626–8627):1473–1476. Level of evidence: 1B

• Manniche C, Lundberg E, Christensen I, et al. Intensive dynamic back exercises for chronic low back pain: a clinical trial. Pain 1991;57:53–63.Level of evidence: 1B

• Hansen FR, Bendix T, Skov P, et al. Intensive dynamic back-muscle exercises, conventional physiotherapy, or placebocontrol treatment of low back pain. Spine 1993;18:98–107. Level of evidence: 1B

• O’Sullivan PB, Twomey LT, Allison GT. Evaluation of specific stabilizing exercise in the treatment of chronic low back pain with radiologic diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis. Spine 1997;22: 2959–67.Level of evidence: 1B

• L.H. Ribeiro, F. Jennings, A. Jones, R. Furtado, J. Natour. Effectiveness of a back school program in low back pain. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 2008; 26: 81-88. Level of evidence: 1B

Resources

[edit | edit source]

http://www.allaboutbackandneckpain.com/understandingconditions/segmentalinstability.asp

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/310353-differential

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Patient education may be important in the treatment of patients with segmental instability. Education should, first of all, focus on preventing loaded flexion movements, as they may create a posterior shift of the disc. Therapy and excercices is usefulll herefor.

The effectivity of back school program has been shown and is more effective than any educational intervention. , level of evidence 1C ]The exercise programme is based on training the patient to draw in the abdominal wall while isometrically contracting the multifidus muscle, and consists.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1X3iPH1T_Q46BOv5FNkJFsK1JFmtizHcll3VxmJrGNBHOLIUs-|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

• A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice.

• An exploratory examination of the association between altered lumbar motor control, joint mobility and low back pain in athletes.

• Comparison of chronic low-back pain patients hip range of motion with lumbar instability.

• Effects of hip exercises for chronic low-back pain patients with lumbar instability.

• Prevalence and individual risk factors associated with clinical lumbar instability in rice farmers with low back pain.

• http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=lumbar+instability

• http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=spine+instability

• http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=lumbar+spine+instability

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Urban JP, Holm S, Maroudas A, Nachemson A. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc: effect of fluid flow on solute transport. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982; 170: 296–302.

- ↑ Brown MF, Hukkanen MV, McCarthy ID, et al. Sensory and sympathetic innervation of the vertebral endplate in patients with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997; 79: 147–153. CrossRef, Medline

- ↑ J. Dvorak, J.A. Antinnes, M. Panjabi, et al. Age and gender related normal motion of the cervical spine, Spine 17 (suppl. 10) (1992) S393–S398

- ↑ J. Dvorak, M.M. Panjabi, D. Grob, et al. Clinical validation of functional flexion/extension radiographs of the cervical spine, Spine 18 (1993) 120–127.

- ↑ https://www.medisavvy.com/lumbar-instability/

- ↑ Kirkaldy-Willis W. Symposium on instability of the lumbar spine : Introduction. Spine 1985; 10: 254-55.

- ↑ Remy S Nizard, Marc Wybier, Jean-Denis Laredo. Radiologic assessment of lumbar intervertebral instability and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Radiol Clin North Am 2001; 39(1): 55-71

- ↑ Alam A., Radiological evaluation of lumbar intervertebral instability. Methods in Aerospace medicine 46(2), 2002

- ↑ Pierre R Dupuis, Ken Yong-Hing, J David Cassidy, William H Kirkaldy Willis. Radiological diagnosis of degenerative lumbar spinal instability. Spine 1985; 10((3): 262-76

- ↑ Alam A., Radiological evaluation of lumbar intervertebral instability. Methods in Aerospace medicine 46(2), 2002

- ↑ McGill SM. Estimation of force and extensor moment contributions of the disc and ligaments at L4–L5. Spine 1988;13:1395–402. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Kang Ahn et al. New physical examination tests for lumbar spondylolisthesis and instability&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: low midline sill sign and interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion. BMC Muscoluskeletal Disorders, 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B

- ↑ P.B. O'Sullivan. Masterclass. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Manual therapy Volume 5, Issue 1, Pages 2–12, February 2000. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ James R Beazell, Melise Mullins and Terry L Grindstaff .Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 Mar; 18(1): 9–14. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ Silvano Ferarri et al., A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr Man Therap., April 2015; 23:14. Level of evidene: 2A

- ↑ Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A

- ↑ Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A