Lumbar Discogenic Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[Image:Physiopedia_pic_2.jpg]] | |||

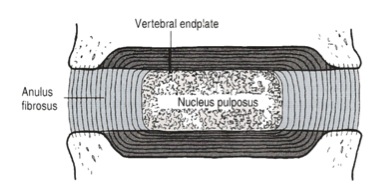

Detailed structure of the intervertebral disc (adapted from Bogduk 2005) | Detailed structure of the intervertebral disc (adapted from Bogduk 2005) | ||

| Line 47: | Line 51: | ||

A primary mechanism behind the diagnosis of discogenic pain is nuclear pulposus migration resulting in a directional preference. Mechanical loading strategies such as repeated movements and sustained positioning have been observed to cause proximal movement and/or abolition of distal symptoms<ref name="McKenzie et al 2003">McKenzie, R. and S. May (2003). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. New Zealand, Orthopedic Physical Therapy Products</ref> <ref name="Aina et al 2004">Aina, A., S. May, et al. (2004). "The centralisation phenomenon of spinal symptoms - a systematic review." Man Ther 9: 134-143</ref>. It has been hypothesised that the mechanism underpinning this response involves a “reduction” or migration of a painful and abnormally displaced nucleus pulposus (within an annular fissure) to a more central and less pain provoking position within the lumbar disc<ref name="McKenzie 1981">McKenzie, R. (1981). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae, Spinal Publication</ref> <ref name="Donelson et al 1997">Donelson, R., C. Aprill, et al. (1997). "A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and anular competence." Spine 22(10): 1115-1122</ref><ref name="Wetzel et al 2003">Wetzel, F. T. and R. Donelson (2003). "The role of repeated end-range/pain response assessment in the management of symptomatic lumbar discs." Spine J 3(2): 146-154</ref>. Associated with centralisation is directional preference, the direction of MLS that result in centralisation <ref name="Wetzel et al 2003" /> <ref name="McKenzie et al 2003" />. Patients with a directional preference due to discogenic pain can be diagnosed as having reducible discogenic pain.<ref name="Ford, Surkitt et al 2011" />. | A primary mechanism behind the diagnosis of discogenic pain is nuclear pulposus migration resulting in a directional preference. Mechanical loading strategies such as repeated movements and sustained positioning have been observed to cause proximal movement and/or abolition of distal symptoms<ref name="McKenzie et al 2003">McKenzie, R. and S. May (2003). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. New Zealand, Orthopedic Physical Therapy Products</ref> <ref name="Aina et al 2004">Aina, A., S. May, et al. (2004). "The centralisation phenomenon of spinal symptoms - a systematic review." Man Ther 9: 134-143</ref>. It has been hypothesised that the mechanism underpinning this response involves a “reduction” or migration of a painful and abnormally displaced nucleus pulposus (within an annular fissure) to a more central and less pain provoking position within the lumbar disc<ref name="McKenzie 1981">McKenzie, R. (1981). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae, Spinal Publication</ref> <ref name="Donelson et al 1997">Donelson, R., C. Aprill, et al. (1997). "A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and anular competence." Spine 22(10): 1115-1122</ref><ref name="Wetzel et al 2003">Wetzel, F. T. and R. Donelson (2003). "The role of repeated end-range/pain response assessment in the management of symptomatic lumbar discs." Spine J 3(2): 146-154</ref>. Associated with centralisation is directional preference, the direction of MLS that result in centralisation <ref name="Wetzel et al 2003" /> <ref name="McKenzie et al 2003" />. Patients with a directional preference due to discogenic pain can be diagnosed as having reducible discogenic pain.<ref name="Ford, Surkitt et al 2011" />. | ||

<br> [[Image: | <br> [[Image:Physiopedia pic 1.jpg]]<br>'''Repeated extension in lying: a common mechanical loading strategy''' | ||

Evaluating response to a mechanical loading strategy (MLS) must be carefully performed. A recent randomised controlled trial on the treatment of reducible discogenic pain used the following criteria based on a synthesis of available evidence and clinical rationale. A positive response to a mechanical loading strategy can be defined as responding to at least 10 repeated movements or a period of sustained positioning by:<br>• An increase in possible range of motion of the MLS during application by at least 50% or <br>• An increase in lumbar active range of motion in any movement by at least 50% after application or<br>• An increase in observed segmental intervertebral motion during lumbar active range of motion testing after application or<br>• An improvement in resting pain (by at least 1 point on a numerical rating scale or by centralisation of symptoms) that lasted for at least 1 minute after application or<br>• A reduction in an observed lateral shift postural abnormality that lasted for at least 1 minute after application | Evaluating response to a mechanical loading strategy (MLS) must be carefully performed. A recent randomised controlled trial on the treatment of reducible discogenic pain used the following criteria based on a synthesis of available evidence and clinical rationale. A positive response to a mechanical loading strategy can be defined as responding to at least 10 repeated movements or a period of sustained positioning by:<br>• An increase in possible range of motion of the MLS during application by at least 50% or <br>• An increase in lumbar active range of motion in any movement by at least 50% after application or<br>• An increase in observed segmental intervertebral motion during lumbar active range of motion testing after application or<br>• An improvement in resting pain (by at least 1 point on a numerical rating scale or by centralisation of symptoms) that lasted for at least 1 minute after application or<br>• A reduction in an observed lateral shift postural abnormality that lasted for at least 1 minute after application | ||

Revision as of 01:45, 17 June 2013

Original Editors - Jon Ford as part of the STOPS Project.

Top Contributors - Evan Thomas, Admin, Jon Ford, Anne-Laure Vanherwegen, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe and Wanda van Niekerk href="Physiopedia:Editors">Read more.

The anatomy and function of the lumbar interverebral disc has been well described in texts[1]. However the diagnosis and management of discogenic pain is controversial. The aim of this article is to synthesise the evidence-based literature from the practitioner's perspective to improve clinical decision making and patient outcomes.

Detailed structure of the intervertebral disc (adapted from Bogduk 2005)

The outer few millimetres of the lumbar disc is innervated, produces clinical type pain when provoked and can be affected by pathological processes/injuries that have the potential to cause LBD[1]. As such, it is reasonable for practitioners to explore clinical and radiological features indicative of discogenic pain. However clear definitions are required. Discogenic pain is pain arising from stimulation of pain sensitive afferents within the annulus fibrosis and is a separate condition from disc herniation with associated radiculopathy[1].

Diagnosis

Much of the controversy around discogenic pain comes from confusion and misinformation on diagnosis. “Disc degeneration” is a poorly defined term perhaps best described as “an aberrant, cell-mediated response to progressive structural failure. The degenerate disc is one with structural failure combined with accelerated or advanced signs of ageing”[2]. The outcome of degeneration can include annular fissures, disc herniation, endplate damage, collapse of the annulus, and disc narrowing which in some cases will produce lumbar related symptoms. Radiological tests such as CT scan and MRI are able to image the external and internal morphology of the intervertebral disc in identifying such structural failure. However these changes in isolation do not predict the presence or absence of lumbar related symptoms[3] and radiology alone is not recommended for the diagnosis of LBD[4]. Lumbar discography is an where the nucleus of the IVD suspected of causing low back pain is injected with radiolucent dye, with the aim of provoking clinical symptoms and revealing morphological abnormalities in the annulus fibrosis. The test is considered positive if the patient’s concordant pain is reproduced upon stimulating the suspected painful disc, and stimulation of adjacent discs does not reproduce the patient’s typical symptoms. Carefully controlled discography is likely to be the best diagnostic tool available for discogenic pain although it has significant risks[5] and has a relatively high false positive rate[6].

It is clear from the literature that a single test for diagnosing discogenic pain is not possible and therefore the methodology of “diagnostic accuracy” to evaluate the validity of clinical tests is somewhat flawed[7]. From a clinical perspective however a number of features have long been associated with discogenic pain based on hypothetical and proven causal mechanisms[8]. These features have been identified in a recent Delphi study of international experts[9] and are summarised in the following table.

| i. Directional preference |

| ii. Symptoms being aggravated by prolonged sitting (>60 minutes) |

| iii. Symptoms being aggravated by lifting |

| iv. Symptoms being aggravated by forward bending |

| v. Symptoms being aggravated by sit to stand |

| vi. Symptoms being aggravated by cough/sneeze |

| vii. History of working in a job with heavy manual handling |

| viii. The mechanism of injury being associated with flexion/rotation and/or compression loading |

| ix. Symptoms much worse the next morning or day after onset of injury |

Clinical features of discogenic pain

There is substantial literature to support the mechanisms underpinning these features as being indicative of discogenic pain[9] and although not validated it makes clinical sense that combining these features with radiological criteria will increase diagnostic certainty.

A primary mechanism behind the diagnosis of discogenic pain is nuclear pulposus migration resulting in a directional preference. Mechanical loading strategies such as repeated movements and sustained positioning have been observed to cause proximal movement and/or abolition of distal symptoms[10] [11]. It has been hypothesised that the mechanism underpinning this response involves a “reduction” or migration of a painful and abnormally displaced nucleus pulposus (within an annular fissure) to a more central and less pain provoking position within the lumbar disc[12] [13][14]. Associated with centralisation is directional preference, the direction of MLS that result in centralisation [14] [10]. Patients with a directional preference due to discogenic pain can be diagnosed as having reducible discogenic pain.[8].

Repeated extension in lying: a common mechanical loading strategy

Evaluating response to a mechanical loading strategy (MLS) must be carefully performed. A recent randomised controlled trial on the treatment of reducible discogenic pain used the following criteria based on a synthesis of available evidence and clinical rationale. A positive response to a mechanical loading strategy can be defined as responding to at least 10 repeated movements or a period of sustained positioning by:

• An increase in possible range of motion of the MLS during application by at least 50% or

• An increase in lumbar active range of motion in any movement by at least 50% after application or

• An increase in observed segmental intervertebral motion during lumbar active range of motion testing after application or

• An improvement in resting pain (by at least 1 point on a numerical rating scale or by centralisation of symptoms) that lasted for at least 1 minute after application or

• A reduction in an observed lateral shift postural abnormality that lasted for at least 1 minute after application

By evaluating responsiveness to a MLS, CT/MRI/discography results and other clinical features a diagnosis of reducible discogenic pain can be made with reasonable confidence. This then informs treatment provision.

Experienced practitioners have hypothesised that more than one type of discogenic pain exists including non-reducible discogenic pain, discitis, end plate disruption, unstable disc, adolescent disc[9]. From a pathoanatomical perspective different morphological and pathophysiological changes may also represent subgroups of clinical relevance such as end plate changes, variations in annular tears and inflammatory/immune responses. Practitioners attempting to diagnose discogenic pain should be aware of these possible subgroups and potential impact on patient presentation.

Treatment

The treatment of all different types of discogenic pain is complex and beyond the bounds of this article. In carefully identified cases of RDP a regime can be applied of regular participant application of helpful MLSs, education, postural advice, lumbar taping techniques and in some cases therapist applied forces.

A summary of the key components of a treatment program for RDP is provided in the table below.

| Treatment protocol component | Rationale |

| Determine whether clinical evidence exists of inflammation (At least 2 of: constant symptoms, getting out of bed at night due to the pain, early morning symptoms > 60 minutes) | The McKenzie method is predominantly for mechanical problems and inflammation, if present, requires specific management |

| In the absence of inflammation, assess for relevant MLS and identify key asterisks. | Confirmation of the most effective MLS to be used for treatment |

| Explanation regarding RDP, treatment options, treatment timeframes and recovery expectations. | Engaging the participant with the treatment process is critical to effective specific treatment |

| Management of inflammation if applicable including provision of information sheet, lumbar taping, recommend pharmacy consultation regarding non-prescription NSAIDs and walking program short of pain onset | Relative rest from aggravating postures/activities, NSAIDs and sub-clinical activity in neutral spine position may prevent an excessive and counter-productive inflammatory response |

| In the absence of inflammation provide an appropriate dosage of the relevant MLS and reassess asterisks. | Additional hypothesis testing |

| Provide homework for regular application of the relevant MLS as an exercise. | Self management of the RDP through home application of MLSs is an essential component of the McKenzie approach |

| Provide a lumbar roll, postural education, a walking program, and lumbar taping in neutral lumbar spine position. These strategies were described on the information sheet | Education of the participant regarding postural control is an essential component of the McKenzie approach |

The application of MLSs need to be carefully performed according to the following criteria:

• Ensuring correct starting position

• Clear and specific participant instructions

• Careful observation by the physiotherapist of participant performance of the MLS

• Provision of verbal and tactile feedback to the participant during and after the MLS

• In most cases instructing the participant to perform the MLS to the point of pain onset. In the event of pain onset progressing further into the MLS range during application, the trial physiotherapist encouraged the participant to progress the movement to the new point of pain onset aiming for end of range when possible

• Close monitoring of symptom response including centralisation during and after the MLS

MLS are generally recommended as a home exercise every 1-2 hours for 6-10 repetitions (with careful patient monitoring of symptom response). Patients with true RDP tend to respond quite quickly over a period of days. If this does not occur then the validity of the diagnosis should be considered.

DPM should rarely be used in isolation to treat discogenic pain, rather combined with other therapeutic methods including manual therapy, motor control training and functional restoration. In the presence of significant psychosocial and neurophysiological factors the administration of DPM should be carefully weighed up against other treatment approaches (eg cognitive behavioural approach, graded activity, neurophysiological education).

This article outlines basic theoretical and clinical considerations around discogenic pain. Further reading and education should be considered for practitioners regularly treating this condition.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bogduk, N. (2012). Clinical and radiological anatomy of the lumbar spine. New York, Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Adams, M. and P. Roughley (2006). "What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it?" Spine 31(18): 2151-2161

- ↑ Videman, T., M. C. BattiÈ, et al. (2003). "Associations between back pain history and lumbar MRI findings." Spine 28(6): 582

- ↑ Dagenais, S., A. Tricco, et al. (2010). "Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines." The Spine Journal 10(6): 514-529

- ↑ Carragee, E., A. Don, et al. (2009). "2009 ISSLS Prize Winner. Does discography cause accelerated progression of degeneration changes in the lumbar disc. A ten-year matched cohort study." Spine 34(21): 2338-2345

- ↑ Carragee, E. J., T. Lincoln, et al. (2006). "A gold standard evaluation of the "discogenic pain" diagnosis as determined by provocative discography." Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31(18): 2115-2123

- ↑ Ford, J., S. Thompson, et al. (2011). "A classification and treatment protocol for low back disorders. Part 1: specific manual therapy." Physical Therapy Reviews 16(3): 168-177

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ford, J., L. Surkitt, et al. (2011). "A classification and treatment protocol for low back disorders. Part 2: directional preference management for reducible discogenic pain." Physical Therapy Reviews 16(6): 423-437

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Chan, A. Y., J. J. Ford, et al. (2013). "Preliminary evidence for the features of non-reducible discogenic low back pain: survey of an international physiotherapy expert panel with the Delphi technique." Physiotherapy

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McKenzie, R. and S. May (2003). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. New Zealand, Orthopedic Physical Therapy Products

- ↑ Aina, A., S. May, et al. (2004). "The centralisation phenomenon of spinal symptoms - a systematic review." Man Ther 9: 134-143

- ↑ McKenzie, R. (1981). The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae, Spinal Publication

- ↑ Donelson, R., C. Aprill, et al. (1997). "A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and anular competence." Spine 22(10): 1115-1122

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wetzel, F. T. and R. Donelson (2003). "The role of repeated end-range/pain response assessment in the management of symptomatic lumbar discs." Spine J 3(2): 146-154