Lower Crossed Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | == Definition/Description == | ||

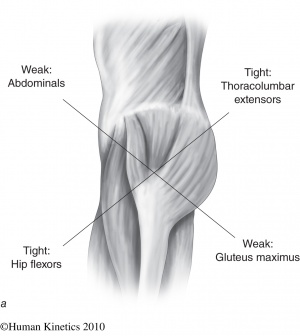

The ‘Unterkreuz syndrome’ is also known as pelvic crossed syndrome, lower crossed syndrome or distal crossed syndrome. The lower crossed syndrome (LCS) is the result of muscles strength imbalances in the lower segment. These imbalances can occur when muscles are constantly shortened en lengthened in relation to each other. A shortened muscle for example shows a lower irritability threshold and will be activated first within a group of muscles. As a result, changes occur in the motor programming. The lower crossed syndrome is characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightness that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body. So tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris on the ventral side. Weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side crosses with weakness of the [[Gluteus Maximus|gluteus maximus]] and medius. The [[Hamstrings|hamstrings]] are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well.[1] This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the [[Pelvis|pelvis]], increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine. This imbalance tends to over-stress both hip joints as well as the lower back. [14] [15] [19] | |||

The ‘Unterkreuz syndrome’ is also known as pelvic crossed syndrome, lower crossed syndrome or distal crossed syndrome. The lower crossed syndrome (LCS) is the result of muscles strength imbalances in the lower segment. These imbalances can occur when muscles are constantly shortened en lengthened in relation to each other. A shortened muscle for example shows a lower irritability threshold and will be activated first within a group of muscles. As a result, changes occur in the motor programming. The lower crossed syndrome is characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightness that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body. So tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris on the ventral side. Weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side crosses with weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius. The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well.[1] This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the pelvis, increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine. This imbalance tends to over-stress both hip joints as well as the lower back. [14] [15] [19] | |||

[[Image:Crossed syndrome.jpg|thumb|center|300px]] | [[Image:Crossed syndrome.jpg|thumb|center|300px]] | ||

| Line 13: | Line 7: | ||

Figure 1: lower crossed syndrome <ref name="Janda" /> | Figure 1: lower crossed syndrome <ref name="Janda" /> | ||

Clinically Relevant Anatomy | |||

The pelvic crossed syndrome involves the trunk muscles. They consist of: | |||

< | • Deep stabilizing muscles: <br>The abdominals:M. Rectus abdominus, M. Obliques internus abdominis, M. Obliques externus abdominis and M.transve<span style="font-size: 13.28px;">rsus abdominis</span> | ||

< | These muscles are inhibited and substituted by activation of the superficial muscles.<br>The thoracolumbar extensors: M.[[Erector spinae|Erector spinae]], M. Multifidus, M. [[Quadratus Lumborum|Quadratus lumborum]] and M. Lattisimus dorsi<br>These muscles are too tight | ||

• The gluteal muscles: M. Gluteus maximus, M. [[Gluteus Medius|Gluteus medius]] and M. [[Gluteus Minimus|Gleuteus Minimus]]. These muscles are weak and inhibited. | |||

• The gluteal muscles: M. Gluteus maximus, M. Gluteus medius and M. Gleuteus Minimus. These muscles are weak and inhibited. | |||

• The hip flexors: M. Iliopsoas and M. Tensor fasciae latae<br> These muscles are too tight. | • The hip flexors: M. Iliopsoas and M. Tensor fasciae latae<br> These muscles are too tight. | ||

• The hamstrings <br> function: compensate for anterior pelvic tilt or an inhibited gluteus maximus. | • The hamstrings <br> function: compensate for anterior pelvic tilt or an inhibited gluteus maximus. | ||

== Epidemiology/Etiology == | == Epidemiology/Etiology == | ||

The concept of the Pelvic Crossed Syndrome was proposed by Janda as an underlying factor in the source and perpetuation of many low back pain syndromes. This was confirmed by Key et al in 2010. [20] <br>In lower crossed syndromes the muscles weaken and others shorten in response to stress (overuse, misuse, abuse). These causes are patient-dependent. It is the patient’s history that should provide this information. <br>To find out what the main cause is, you can ask about the patient’s postural history of constrained postures from repetitive tasks and sedentary lifestyle. [2] | |||

The concept of the Pelvic Crossed Syndrome was | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

This muscle imbalance creates joint dysfunction ( | This muscle imbalance creates joint dysfunction (ligamentous strain and increased pressure particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, the [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_joint SI joint] and the hip joint), joint pain (lower back, hip and knee) and specific postural changes (lower back, hip and knee), such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external leg rotation and knee hyperextension. But it also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: [[Thoracic Hyperkyphosis|increased thoracic kyphosis]] and increased in cervical lordosis. [3] [4]<br>There are two subtypes, A and B, of lower crossed syndrome. The two types are similar and involve the same main muscle imbalance characteristics. For type A the imbalance manifests mainly in the hip, while for type B the imbalance mainly manifests in the lower back. We can distinguish between the two subgroups based upon the altered postural alignment and also changed regional myofascial activation patterns. An observation of the lower pole of the thorax and the anterolateral abdominal wall shows whether there are problems with the activity level and balance between the diaphragm and transversus abdominis. Mostly, there is an underactivity of the deep transversus associated with either increased or decreased superficial activity in the obliques and rectus. [11] | ||

<u>'''Type A'''</u>: The first subgroup is the posterior pelvic crossed syndrome. In this subgroup | <u>'''Type A'''</u>: The first subgroup is the posterior pelvic crossed syndrome. In this subgroup there is a domination of the axial extensor. [11] Because the hip flexors are shortened, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly and the hip and knee are in slight flexion. This gives an expression for the compensatory hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine and hyperkyphosis in the transition from thoracic to lumbar spine. In general, this imbalance occurs over the thoracolumbar junction between the dorsal hinge and the mid lumbar spine.It is called a ‘Central Posterior Clinch’, by which they mean an automatic reflex hyperactivity, due to a tonic, bilateral, posterior ‘bracing’ response, co-associated with observable underactivity of the complete anterolateral abdominal wall. This leads to a decrease in the quality of breathing and of the postural control in a typical manner. We can determine that the pelvis moves back and the thorax moves forward, which creates a more oblique relationship to each other. Above that the entire thorax will move up, due to the minimal inferior stabilization created by the abdominals. The infra-sternal angle will go up to more than 90° and the postero-inferior thorax will be hyper-stabilized through which it will cause a limited postero-lateral costo-vertebral movement. [11,12]. | ||

The more anterior and elevated position of the thorax will disturb the stabilization synergies of the Lower Pelvic Unit. The patient will lift the thorax during inspiration, due to a synergy of pectoral lifting and Central Posterior Clinch, which causes an upper chest breathing pattern. This means that the active exhalation will be difficult, because the abdominal activation fails to bring the thorax down and back into the more expiratory caudal (or neutral) position. The abdominal activation is also not sufficient to create the essential intra abdominal pressure. We will notice that the expiratory phase is shortened. This problem arises when the coordination and co-activation between the transverses and the diaphragm is missing. The patient is forced to use the Central Posterior Clinch behavior, which results in an overactivity of the psoas. [11] | |||

<u>'''Type B'''</u>: | <u>'''Type B'''</u>: It is also called ‘The Anterior Pelvic Crossed syndrome. In this type the abdominal muscles are too weak and too short. This is associated with a predominant tendency of the axial flexor activity.[11] The compensation is reflected by a minimal hypolordosis of the lumbar spine, a hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine and protraction of the head. The pelvis is postured more anteriorly and the knees are in hyperextension. [1][5] <br><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 63: | Line 45: | ||

[[Image:Type B.jpg|thumb|center]] Figure 3: type B <ref name="Janda" /> | [[Image:Type B.jpg|thumb|center]] Figure 3: type B <ref name="Janda" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

| Line 69: | Line 51: | ||

*'''OBSERVATION IN ERECT STANDING AND GAIT''' <ref name="Liebenson" /> | *'''OBSERVATION IN ERECT STANDING AND GAIT''' <ref name="Liebenson" /> | ||

- | - Look at the position of the pelvis. There is usually an increase of anterior tilt of the pelvis. This can we associated with increased lumbar lordosis. <br>- Next the shape, size and tone of the tightened/inhibited muscles. (see Definition/Description) | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 93: | Line 75: | ||

<br><u>Thigh adductors</u> are tested with the patient lying supine at the edge of the plinth. Tight hamstrings may contribute to the range limitation. If this situation occurs, bending the knee should increase the range of movement. | <br><u>Thigh adductors</u> are tested with the patient lying supine at the edge of the plinth. Tight hamstrings may contribute to the range limitation. If this situation occurs, bending the knee should increase the range of movement. | ||

<br><u>The piriformis muscle</u> is tested with the patient in a supine position | <br><u>The [[Piriformis|piriformis]] muscle</u> is tested with the patient in a supine position. If the muscle is tight, the end feel is hard and may be associated with pain deep in the buttocks. | ||

<br><u>Quadratus lumborum</u> is difficult to examine. In principle, passive trunk side bending is tested while the patient assumes a side-lying position. The reference point is the level of inferior angle of the scapula. A simpler screening test entails observation of the spinal curve during active lateral flexion of the trunk. | <br><u>Quadratus lumborum</u> is difficult to examine. In principle, passive trunk side bending is tested while the patient assumes a side-lying position. The reference point is the level of inferior angle of the scapula. A simpler screening test entails observation of the spinal curve during active lateral flexion of the trunk. | ||

| Line 99: | Line 81: | ||

<br><u>Spinal erectors</u> are also difficult to examine. As a screening test, forward bending in a short sit allows observation of the gradual curvature of the spine. | <br><u>Spinal erectors</u> are also difficult to examine. As a screening test, forward bending in a short sit allows observation of the gradual curvature of the spine. | ||

<br><u>Triceps surae</u> are tested by performing passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Normally, the therapist should be able to achieve passive dorsiflexion to 90 degrees. | <br><u>Triceps surae</u> are tested by performing passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Normally, the therapist should be able to achieve passive dorsiflexion to 90 degrees. | ||

== Physical Therapy management == | == Physical Therapy management == | ||

The treatment of tightness is not in strengthening | The treatment of tightness is not in strengthening as it would increase tightness and possibly result in more pronounced weakness, but in stretching, oriented toward influencing the noncontractile but retractile connective tissue of the muscle. Stretching of tight muscles also results in improved strength of inhibited antagonistic muscles, probably mediated via the Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation. <br>(grades of recommendation: 2C) <ref>Chaitow L., DeLany J.W., (2002). Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: the lower body: Churchill livingstone. (p.26,36)</ref> <ref>Roberts, J., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1B</ref> | ||

Normalizing the short and weak muscles, with the objective of restoring balance. This may involve purely soft tissue approaches. Stretch the specific muscle for a duration of 15 seconds. A five week active stretching program significantly increases active and passive ROM in the lower extremity. <ref>Roberts, J., &amp; Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1B</ref> (level of evidence: 1B) | Normalizing the short and weak muscles, with the objective of restoring balance. This may involve purely soft tissue approaches. Stretch the specific muscle for a duration of 15 seconds. A five week active stretching program significantly increases active and passive ROM in the lower extremity. <ref>Roberts, J., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1B</ref> (level of evidence: 1B) | ||

Iliopsoas stretch (and rectus femoris) <ref>Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C</ref><br>The patient is placed in Thomas position. The not-stretched side is maximally flexed to stabilize tot pelvis and flatten the lumbar spine. The other leg is normally in flexed position because of the tightness of the iliopsoas. Push this leg into the neutral position (onto the table). Hold this position 15 seconds.<br> | Iliopsoas stretch (and rectus femoris) <ref>Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C</ref><br>The patient is placed in Thomas position. The not-stretched side is maximally flexed to stabilize tot pelvis and flatten the lumbar spine. The other leg is normally in flexed position because of the tightness of the iliopsoas. Push this leg into the neutral position (onto the table). Hold this position 15 seconds.<br> | ||

If you want to integrate the rectus femoris into this stretch, bent the knee in more than 90° while performing the iliopsoas stretch. <br>(level of evidence: 2C)<br> <br>Erector spinae stretch <ref>Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C</ref><br>Sit on the floor with your knees bent in 90° and your feet half a meter in front. | If you want to integrate the rectus femoris into this stretch, bent the knee in more than 90° while performing the iliopsoas stretch. <br>(level of evidence: 2C)<br> <br>Erector spinae stretch <ref>Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C</ref><br>Sit on the floor with your knees bent in 90° and your feet half a meter in front. Grab your ankles and bent your chin to your chest, flex forward and down as far as possible. Pull your trunk downwards by pulling on the ankles. Exhale and stretch. Hold this position 15 seconds.<br> | ||

The solution for these common patterns is to identify both the shortened and the weakened structures and to set about normalizing their dysfunctional status. This might involve: | |||

The solution for these common patterns is to identify both the shortened and the weakened structures and to set about normalizing their dysfunctional status. This might involve: | |||

(grades of recommendation: C) <br><br> | *deactivating [[Trigger Points|trigger points]] and removing muscular adhesions. Perform myofascial release and trigger-point massage to the gluteus muscles, iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae. <br>(grades of recommendation: B) <ref>Simons D.G., Understanding Effective Treatments of Myofascial Trigger Points: Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2002, Volume 6, issue 2. fckLRLevel of evidence: 1A</ref> | ||

*Laser or [[Ultrasound therapy|ultrasound]] therapy on the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae. | |||

*Regaining the normal lumbar flexion mobility | |||

*[[Core stability|Core stabilization]] exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles. | |||

*Re-education of posture and body usage. It is necessary to relearn the specific activiation of every element within the Lower Pelvic Unit. This will establish the important fundamental patterns of intra-pevlic control and will also integrate these patterns into basis functional patterns of movement control iniated from the pelvis. | |||

*Retraining patients with Posterior Pelvic Crossed Syndrome<br>It is important to improve the active exhalation, which will bring the thorax caudally on a stable pelvis. It is important to assist the patient, while maintaining the neutral position.. While executing this exercise, it is crucial that the patient breaths down and not up. The patient has to be able to create sufficient intra-abdominal pressure , while maintaining a regular breathing pattern. <br>The patient has to lie down on his back, in supine supported hip flexion to eliminate gravity. The therapist ask the patient to ‘breathe down to the lower placed hand’. It is then important to encourage an active and long exhalation. This gives the patient the sense of the required action. When the correct pattern is mastered we can progress into unsupported hip flexion. It is important to push the ribs wide and back, without lifting the thorax. To realize this, the client is asked to push out sideways into the hands of the therapist.[<ref>Key J. (2013), ‘The core’: Understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction, Journal of Bodywork &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Movement Therapies 17, p. 541- 559fckLRLevel of evidence: 1A</ref>, <ref>Ishida, H., Hirose, R., Watanabe, S., 2012. Comparison of changes in the contraction of the lateral abdominal muscles between the abdominal drawing-in maneuver and breathe held at the maximum expiratory level. Man. Ther. 17 (5), 427- 431.fckLRLevel of Evidence: 2C</ref>](grades of recommendation: C) <br><br> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /><br> | <references /><br> | ||

Revision as of 11:26, 4 December 2016

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The ‘Unterkreuz syndrome’ is also known as pelvic crossed syndrome, lower crossed syndrome or distal crossed syndrome. The lower crossed syndrome (LCS) is the result of muscles strength imbalances in the lower segment. These imbalances can occur when muscles are constantly shortened en lengthened in relation to each other. A shortened muscle for example shows a lower irritability threshold and will be activated first within a group of muscles. As a result, changes occur in the motor programming. The lower crossed syndrome is characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightness that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body. So tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris on the ventral side. Weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side crosses with weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius. The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well.[1] This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the pelvis, increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine. This imbalance tends to over-stress both hip joints as well as the lower back. [14] [15] [19]

Figure 1: lower crossed syndrome [1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The pelvic crossed syndrome involves the trunk muscles. They consist of:

• Deep stabilizing muscles:

The abdominals:M. Rectus abdominus, M. Obliques internus abdominis, M. Obliques externus abdominis and M.transversus abdominis

These muscles are inhibited and substituted by activation of the superficial muscles.

The thoracolumbar extensors: M.Erector spinae, M. Multifidus, M. Quadratus lumborum and M. Lattisimus dorsi

These muscles are too tight

• The gluteal muscles: M. Gluteus maximus, M. Gluteus medius and M. Gleuteus Minimus. These muscles are weak and inhibited.

• The hip flexors: M. Iliopsoas and M. Tensor fasciae latae

These muscles are too tight.

• The hamstrings

function: compensate for anterior pelvic tilt or an inhibited gluteus maximus.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

The concept of the Pelvic Crossed Syndrome was proposed by Janda as an underlying factor in the source and perpetuation of many low back pain syndromes. This was confirmed by Key et al in 2010. [20]

In lower crossed syndromes the muscles weaken and others shorten in response to stress (overuse, misuse, abuse). These causes are patient-dependent. It is the patient’s history that should provide this information.

To find out what the main cause is, you can ask about the patient’s postural history of constrained postures from repetitive tasks and sedentary lifestyle. [2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

This muscle imbalance creates joint dysfunction (ligamentous strain and increased pressure particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, the SI joint and the hip joint), joint pain (lower back, hip and knee) and specific postural changes (lower back, hip and knee), such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external leg rotation and knee hyperextension. But it also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: increased thoracic kyphosis and increased in cervical lordosis. [3] [4]

There are two subtypes, A and B, of lower crossed syndrome. The two types are similar and involve the same main muscle imbalance characteristics. For type A the imbalance manifests mainly in the hip, while for type B the imbalance mainly manifests in the lower back. We can distinguish between the two subgroups based upon the altered postural alignment and also changed regional myofascial activation patterns. An observation of the lower pole of the thorax and the anterolateral abdominal wall shows whether there are problems with the activity level and balance between the diaphragm and transversus abdominis. Mostly, there is an underactivity of the deep transversus associated with either increased or decreased superficial activity in the obliques and rectus. [11]

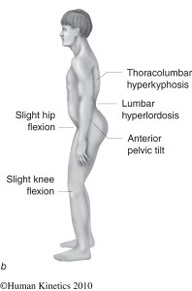

Type A: The first subgroup is the posterior pelvic crossed syndrome. In this subgroup there is a domination of the axial extensor. [11] Because the hip flexors are shortened, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly and the hip and knee are in slight flexion. This gives an expression for the compensatory hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine and hyperkyphosis in the transition from thoracic to lumbar spine. In general, this imbalance occurs over the thoracolumbar junction between the dorsal hinge and the mid lumbar spine.It is called a ‘Central Posterior Clinch’, by which they mean an automatic reflex hyperactivity, due to a tonic, bilateral, posterior ‘bracing’ response, co-associated with observable underactivity of the complete anterolateral abdominal wall. This leads to a decrease in the quality of breathing and of the postural control in a typical manner. We can determine that the pelvis moves back and the thorax moves forward, which creates a more oblique relationship to each other. Above that the entire thorax will move up, due to the minimal inferior stabilization created by the abdominals. The infra-sternal angle will go up to more than 90° and the postero-inferior thorax will be hyper-stabilized through which it will cause a limited postero-lateral costo-vertebral movement. [11,12].

The more anterior and elevated position of the thorax will disturb the stabilization synergies of the Lower Pelvic Unit. The patient will lift the thorax during inspiration, due to a synergy of pectoral lifting and Central Posterior Clinch, which causes an upper chest breathing pattern. This means that the active exhalation will be difficult, because the abdominal activation fails to bring the thorax down and back into the more expiratory caudal (or neutral) position. The abdominal activation is also not sufficient to create the essential intra abdominal pressure. We will notice that the expiratory phase is shortened. This problem arises when the coordination and co-activation between the transverses and the diaphragm is missing. The patient is forced to use the Central Posterior Clinch behavior, which results in an overactivity of the psoas. [11]

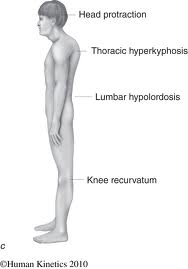

Type B: It is also called ‘The Anterior Pelvic Crossed syndrome. In this type the abdominal muscles are too weak and too short. This is associated with a predominant tendency of the axial flexor activity.[11] The compensation is reflected by a minimal hypolordosis of the lumbar spine, a hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine and protraction of the head. The pelvis is postured more anteriorly and the knees are in hyperextension. [1][5]

Figure 2: type A [1]

Figure 3: type B [1]

Examination[edit | edit source]

- OBSERVATION IN ERECT STANDING AND GAIT [2]

- Look at the position of the pelvis. There is usually an increase of anterior tilt of the pelvis. This can we associated with increased lumbar lordosis.

- Next the shape, size and tone of the tightened/inhibited muscles. (see Definition/Description)

- ACTIVE EXAMINATION: [2]

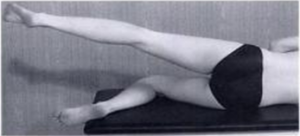

Hip extension - is examined to analyze the hyperextension phase of the hip in gait. Use a straight leg lifting.

Hip abduction –the patient with LCS, will combine the abduction with an lateral rotation and a flexion of the hip.

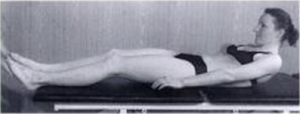

Trunk curl up – is tested to estimate the interplay between usually strong iliopsoas and the abdominal muscles.

Figure 4: Hip Abduction [2]

Figure 5: Trunk Curl up [2]

- PASSIVE EXAMINATION : [2]

Hipflexors are tested with the patient in a modified Thomas position. This test can be influenced by the stretch of the joint capsule and thus more specific test should be performed to confirm the tightness of the adductors. Confirmation of tightness is clear when excessive soft tissue resistance and decreased range of motion are encountered on application of pressure in the following directions.

The tightness of Hamstrings are tested with a straight leg test.

Thigh adductors are tested with the patient lying supine at the edge of the plinth. Tight hamstrings may contribute to the range limitation. If this situation occurs, bending the knee should increase the range of movement.

The piriformis muscle is tested with the patient in a supine position. If the muscle is tight, the end feel is hard and may be associated with pain deep in the buttocks.

Quadratus lumborum is difficult to examine. In principle, passive trunk side bending is tested while the patient assumes a side-lying position. The reference point is the level of inferior angle of the scapula. A simpler screening test entails observation of the spinal curve during active lateral flexion of the trunk.

Spinal erectors are also difficult to examine. As a screening test, forward bending in a short sit allows observation of the gradual curvature of the spine.

Triceps surae are tested by performing passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Normally, the therapist should be able to achieve passive dorsiflexion to 90 degrees.

Physical Therapy management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of tightness is not in strengthening as it would increase tightness and possibly result in more pronounced weakness, but in stretching, oriented toward influencing the noncontractile but retractile connective tissue of the muscle. Stretching of tight muscles also results in improved strength of inhibited antagonistic muscles, probably mediated via the Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation.

(grades of recommendation: 2C) [3] [4]

Normalizing the short and weak muscles, with the objective of restoring balance. This may involve purely soft tissue approaches. Stretch the specific muscle for a duration of 15 seconds. A five week active stretching program significantly increases active and passive ROM in the lower extremity. [5] (level of evidence: 1B)

Iliopsoas stretch (and rectus femoris) [6]

The patient is placed in Thomas position. The not-stretched side is maximally flexed to stabilize tot pelvis and flatten the lumbar spine. The other leg is normally in flexed position because of the tightness of the iliopsoas. Push this leg into the neutral position (onto the table). Hold this position 15 seconds.

If you want to integrate the rectus femoris into this stretch, bent the knee in more than 90° while performing the iliopsoas stretch.

(level of evidence: 2C)

Erector spinae stretch [7]

Sit on the floor with your knees bent in 90° and your feet half a meter in front. Grab your ankles and bent your chin to your chest, flex forward and down as far as possible. Pull your trunk downwards by pulling on the ankles. Exhale and stretch. Hold this position 15 seconds.

The solution for these common patterns is to identify both the shortened and the weakened structures and to set about normalizing their dysfunctional status. This might involve:

- deactivating trigger points and removing muscular adhesions. Perform myofascial release and trigger-point massage to the gluteus muscles, iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae.

(grades of recommendation: B) [8] - Laser or ultrasound therapy on the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae.

- Regaining the normal lumbar flexion mobility

- Core stabilization exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles.

- Re-education of posture and body usage. It is necessary to relearn the specific activiation of every element within the Lower Pelvic Unit. This will establish the important fundamental patterns of intra-pevlic control and will also integrate these patterns into basis functional patterns of movement control iniated from the pelvis.

- Retraining patients with Posterior Pelvic Crossed Syndrome

It is important to improve the active exhalation, which will bring the thorax caudally on a stable pelvis. It is important to assist the patient, while maintaining the neutral position.. While executing this exercise, it is crucial that the patient breaths down and not up. The patient has to be able to create sufficient intra-abdominal pressure , while maintaining a regular breathing pattern.

The patient has to lie down on his back, in supine supported hip flexion to eliminate gravity. The therapist ask the patient to ‘breathe down to the lower placed hand’. It is then important to encourage an active and long exhalation. This gives the patient the sense of the required action. When the correct pattern is mastered we can progress into unsupported hip flexion. It is important to push the ribs wide and back, without lifting the thorax. To realize this, the client is asked to push out sideways into the hands of the therapist.[[9], [10]](grades of recommendation: C)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJanda - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLiebenson - ↑ Chaitow L., DeLany J.W., (2002). Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: the lower body: Churchill livingstone. (p.26,36)

- ↑ Roberts, J., &amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1B

- ↑ Roberts, J., &amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1B

- ↑ Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C

- ↑ Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of het Spine: A Practitioner's Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins.fckLRLevel of evidence: 2C

- ↑ Simons D.G., Understanding Effective Treatments of Myofascial Trigger Points: Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2002, Volume 6, issue 2. fckLRLevel of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Key J. (2013), ‘The core’: Understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction, Journal of Bodywork &amp;amp;amp;amp; Movement Therapies 17, p. 541- 559fckLRLevel of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Ishida, H., Hirose, R., Watanabe, S., 2012. Comparison of changes in the contraction of the lateral abdominal muscles between the abdominal drawing-in maneuver and breathe held at the maximum expiratory level. Man. Ther. 17 (5), 427- 431.fckLRLevel of Evidence: 2C