Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 331: | Line 331: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

<br>There are different definitions of low back pain:<br>The World Health Organization says low back pain is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity of any sort. Low back pain refers to pain of variable duration in an area of the anatomy afflicted so often that it has become a paradigm of responses to external and internal stimuli.<ref name="29">Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2003;81:671-676</ref> | <br>There are different definitions of low back pain:<br>The World Health Organization says low back pain is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity of any sort. Low back pain refers to pain of variable duration in an area of the anatomy afflicted so often that it has become a paradigm of responses to external and internal stimuli.<ref name="29">Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2003;81:671-676</ref> | ||

There is some evidence suggesting a relation between respiration and low back pain. A non-optimal coordination of postural and respiratory functions of trunk muscles is proposed as an explanation for this relationship. A study has shown that significantly more altered breathing patterns were observed in chronic LBP-patients during performance of the motor control testing nevertheless further research regarding the role of the diaphragm in the occurrence and/or recurrence of low back pain, and possible implications, is required.<ref name="11">Roussel et al., “Altered breathing patterns during lumbopelvic motor control tests in chronic low back pain: a case–control study”, European Spine Journal, 2009, 18.7: 1066-1073. (level of evidence: 3B)</ref> (level of evidence: 3) <br>Motor control is a key component in injury prevention. Loss of motor control involves failure to control joints, commonly because of incoordination of the agonist-antagonist muscle co-activation.<br>In the characteristics/… chapter the relation between BPD and low back pain is discussed in further detail.<br>Back pain is then further categorised into specific or non-specific back pain.<ref name="1">Anthony Delitto et al., “Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association”, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2012 April, 42(4): A1–57 (level of evidence: 1B)</ref> (level of evidence: 1) In specific low back pain, by definition, a patho-anatomical relationship can be demonstrated between the pain and one or more pathological processes, including compression of neural structures, joint inflammation, and/or instability of one or more spinal motion segments. Specific diagnostic investigations and cause-directed treatments should be initiated to examine this.3 (level of evidence: 2) | There is some evidence suggesting a relation between respiration and low back pain. A non-optimal coordination of postural and respiratory functions of trunk muscles is proposed as an explanation for this relationship. A study has shown that significantly more altered breathing patterns were observed in chronic LBP-patients during performance of the motor control testing nevertheless further research regarding the role of the diaphragm in the occurrence and/or recurrence of low back pain, and possible implications, is required.<ref name="11">Roussel et al., “Altered breathing patterns during lumbopelvic motor control tests in chronic low back pain: a case–control study”, European Spine Journal, 2009, 18.7: 1066-1073. (level of evidence: 3B)</ref> (level of evidence: 3) <br>Motor control is a key component in injury prevention. Loss of motor control involves failure to control joints, commonly because of incoordination of the agonist-antagonist muscle co-activation.<br>In the characteristics/… chapter the relation between BPD and low back pain is discussed in further detail.<br>Back pain is then further categorised into specific or non-specific back pain.<ref name="1">Anthony Delitto et al., “Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association”, Journal of Orthopaedic &amp; Sports Physical Therapy, 2012 April, 42(4): A1–57 (level of evidence: 1B)</ref> (level of evidence: 1) In specific low back pain, by definition, a patho-anatomical relationship can be demonstrated between the pain and one or more pathological processes, including compression of neural structures, joint inflammation, and/or instability of one or more spinal motion segments. Specific diagnostic investigations and cause-directed treatments should be initiated to examine this.3 (level of evidence: 2) | ||

The Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) defines low back pain as a term that refers to ‘non-specific low back pain’, which is defined as low back pain that does not have a specified physical cause, such as nerve root compression (Lumbar Radiculopathy), trauma, infection or the presence of a tumor. This is the case in about 90% of all low back pain patients. In 80–90% of cases, patients their complaints diminish spontaneously within 4–6 weeks. Approximately 65% of patients who consult their primary care physician are free of symptoms after 12 weeks. Recurrent low back pain is common.30 Non-specific low back pain is also defined as back pain when there is no clear causal relationship between the symptoms, physical findings and imaging findings.3 (level of evidence: 2) Non-specific low back pain is the most common type of back pain to occur, and accounts for 85% of all back pain cases.1 (level of evidence: 1) | The Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) defines low back pain as a term that refers to ‘non-specific low back pain’, which is defined as low back pain that does not have a specified physical cause, such as nerve root compression (Lumbar Radiculopathy), trauma, infection or the presence of a tumor. This is the case in about 90% of all low back pain patients. In 80–90% of cases, patients their complaints diminish spontaneously within 4–6 weeks. Approximately 65% of patients who consult their primary care physician are free of symptoms after 12 weeks. Recurrent low back pain is common.30 Non-specific low back pain is also defined as back pain when there is no clear causal relationship between the symptoms, physical findings and imaging findings.3 (level of evidence: 2) Non-specific low back pain is the most common type of back pain to occur, and accounts for 85% of all back pain cases.1 (level of evidence: 1) | ||

| Line 806: | Line 806: | ||

<rss>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1-UFW4KkLsPjVlBi3wM7t-SugMHpfpN_BxFjjpTPdh2a4sKsAe|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss> | <rss>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1-UFW4KkLsPjVlBi3wM7t-SugMHpfpN_BxFjjpTPdh2a4sKsAe|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss> | ||

== References<br> == | == References<br> == | ||

<references /><br> | |||

[[Category:Lumbar]] [[Category:Low_Back_Pain]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | [[Category:Lumbar]] [[Category:Low_Back_Pain]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | ||

Revision as of 17:24, 25 January 2017

Original Editors - Jeroen Verwichte

Top Contributors - Arno De Winne, Margaux Reynders, Julie Lhost Aimee Tow, Jeroen Verwichte, Axel Antoine, Haegeman Nicolas, Charlotte Fastenaekels, Loïc Byl, Admin, 127.0.0.1, Ian Duerinckx, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Evan Thomas, Oyemi Sillo and Leon Chaitow

Search strategy[edit | edit source]

Database: pubmed, web of science and pedro <span style="font-size: 9pt; font-family: Verdana; color: windowtext;" />Keywords: “ Low back pain”, “ Breathing disorder”, “physiotherapy”, “yoga”, “ breathing therapy”, “ breathing exercises”, “ inspiratory training” ==

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

There are different definitions of low back pain:

The World Health Organization says low back pain is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity of any sort. Low back pain refers to pain of variable duration in an area of the anatomy afflicted so often that it has become a paradigm of responses to external and internal stimuli.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

There is some evidence suggesting a relation between respiration and low back pain. A non-optimal coordination of postural and respiratory functions of trunk muscles is proposed as an explanation for this relationship. A study has shown that significantly more altered breathing patterns were observed in chronic LBP-patients during performance of the motor control testing nevertheless further research regarding the role of the diaphragm in the occurrence and/or recurrence of low back pain, and possible implications, is required.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title (level of evidence: 3)

Motor control is a key component in injury prevention. Loss of motor control involves failure to control joints, commonly because of incoordination of the agonist-antagonist muscle co-activation.

In the characteristics/… chapter the relation between BPD and low back pain is discussed in further detail.

Back pain is then further categorised into specific or non-specific back pain.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title (level of evidence: 1) In specific low back pain, by definition, a patho-anatomical relationship can be demonstrated between the pain and one or more pathological processes, including compression of neural structures, joint inflammation, and/or instability of one or more spinal motion segments. Specific diagnostic investigations and cause-directed treatments should be initiated to examine this.3 (level of evidence: 2)

The Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) defines low back pain as a term that refers to ‘non-specific low back pain’, which is defined as low back pain that does not have a specified physical cause, such as nerve root compression (Lumbar Radiculopathy), trauma, infection or the presence of a tumor. This is the case in about 90% of all low back pain patients. In 80–90% of cases, patients their complaints diminish spontaneously within 4–6 weeks. Approximately 65% of patients who consult their primary care physician are free of symptoms after 12 weeks. Recurrent low back pain is common.30 Non-specific low back pain is also defined as back pain when there is no clear causal relationship between the symptoms, physical findings and imaging findings.3 (level of evidence: 2) Non-specific low back pain is the most common type of back pain to occur, and accounts for 85% of all back pain cases.1 (level of evidence: 1)

Low back pain is not a disease in itself, but rather a symptom with many causes.2 (level of evidence 2) The term “low back pain” refers to pain in the back from the level of the lowest rib down to the gluteal fold, with or without radiation into the legs.3 (level of evidence: 2)

Low back pain is traditionally classified as acute (lasting up to 6 weeks and arisen for the first time in a patient’s life, or after a pain-free interval of at least six months), sub-acute (6–12 weeks), or chronic (more than 12 weeks).3 (level of evidence: 2) According to different studies, forty percent of the patients with acute low back pain are at an elevated risk of developing chronic low back pain.1 (level of evidence: 1). This temporal classification, often does not adequately reflect the transition from acute to chronic pain. The typical element of chronification is the increasing multidimensionality of pain, involving a loss of mobility, restriction of function, abnormal perception and mood, unfavorable cognitive patterns, pain-related behavior, and, on the social level, disturbances of social interaction and occupational difficulties.3 (level of evidence: 2)

Breathing pattern disorders (BPD), also known as dysfunctional breathing, are respiratory patterns that are abnormal. Breathing can become dysfunctional when the person is unable to breathe efficiently. But is becomes dysfunctional when the breathing is inappropriate, unhelpful or inefficient in responding to environmental conditions and the changing needs of the individual.13 (level of evidence: 4). BPD are in relation with overbreathing which can go from simple upper chest breathing to hyperventilation, which is very extreme. Hyperventilation is the most recognised form of dysfunctional breathing.14

BPD can be chronic or can be defined as changes in the breathing pattern that cannot be ascribed to a specific diagnosis. This disorder can cause respiratory and non-respiratory complaints. BPD is a distinct syndrome, they are not an inevitable result of pathologic changes due to illness/disease.15 (level of evidence: 4)

BPD can be caused by some factors but those can different from the factors that perpetuate it. Once a pattern is established and the disorder becomes habituated it can be a disorder of its own.15 (level of evidence: 4)

BPD can, in long term conditions, destabilise mind, mood, metabolism, inspiratory muscle hypertonification and in some cases can also cause motor control impairment in for example postural muscles because of abnormal levels of O2 and CO2 in the brain. It can also play a part in chronic fatigue, depression/anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, fibromyalgia, neck-, back- and pelvic pain.16 (level of evidence: 2)

Symptoms of BPD include dyspnoea, yawning/sighing, unable to get a deep enough breath and ‘air hunger’. A common feature in BPD is that the breathing pattern irregular is. This means that sometimes the pattern is normal and other times it’s irregular which makes diagnosis and observation difficult.

What is defined as a normal breathing pattern:

• Abdominal, not chest breathing should initiate inhalation, which then expand outwards during inhalation.

• Lifting the chest up while breathing is faulty

• Lack of or a upwards lateral lifting pattern is faulty

• Paradoxical breathing is faulty

• Breathing that has no clavicular grooving formed by chronic chest lifting

In a systematic review (level of evidence: 2A) they have found a significant correlation between low back pain and breathing pattern disorders. This includes both pulmonary pathologies and non-specified breathing pattern disorders.17 (level of evidence: 2). Another study (level of evidence: 2B) showed that the presence of a respiratory disease such as an BPD, is a predictor for low back pain.18 (level of evidence: 2)

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

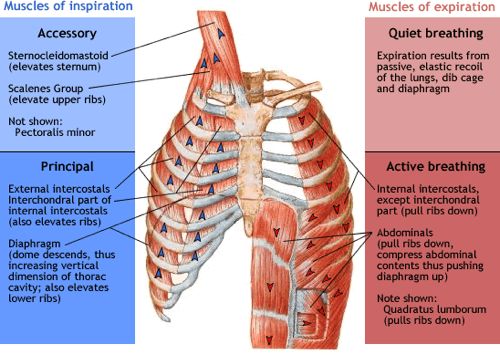

The thoracic cage is formed by the spine, rib cage and associated muscles. While the spine and the ribs form the sides and the tops, the diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cage. The muscles connecting the twelve pairs of ribs are called the intercostal muscles, and the muscles running from the head and neck to the sternum and the first two ribs are the sternocleidomastoids and the scalenes.

Muscles used for ventilation:

- Inspiratory muscles: external intercostals, diaphragm, sternocleidomastoids, scalenes

- Expiratory muscles: internal intercostals and the abdominal muscles (expiration during quiet breathing is called passive expiration, because it involves passive elastic recoil)[1] [2]

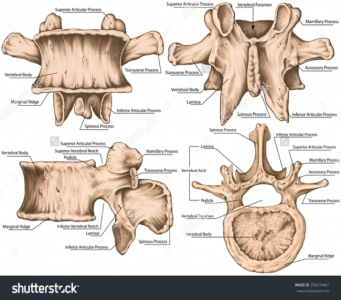

The region of low back pain is the lumbar spine. There are 5 vertebras: L1-L5. And each time there is an intercalated disk between 2 vertebras.

Osteology of a lumbar vertebra:

(23)

The biggest part of a lumbar vertebra is the body, it’s the most ventral located part of the vertebral. At the dorsal side we can find the spinous process with at each side a transverse process. In the middle of the vertebra there is a big hole: the vertebral foramen.14

The back is supported by many muscles:

• Latissimus dorsi:

o Origin: Fascia thoracolumbalis, spinosus process (Th7-L5), crista iliaca, 9th-12th rib

o Insertion: Crista tuberculi minoris humeri

o Function: extension, internal rotation, adduction

• Erector spinae (lateral tract, medial tract)

• Lateral tract (sacrospinal system)

o Longissimus Capitis

Origin: Transverse process (Th1-Th3), transverse- and spinous process (C4- C7)

Insertion: Mastoid process

Function: dorsal extension of the head, lateral flexion

o Longissimus Thoracis

Origin: Os sacrum, crista iliaca

Insertion: 2nd- 12th rib, costal process (L1-L5), transverse process (Th1-Th12)

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion

o Longissimus Cervicis

Origin: Transverse process (Th1-Th6)

Insertion: Transverse process (C2-C5)

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion

o Iliocostalis Lumborum

Origin: Os sacrum, fascia thoracolumbalis, crista iliaca

Insertion: 6th-12th rib, transverse process (L1-L3)

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion

o Iliocostalis Thoracis

Origin: 7th-12th rib

Insertion: 1st-6th rib

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion

o Iliocostalis Cervicis

Origin: 3rd-7th rib

Insertion: transverse process (Th4-Th6)

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion

• Lateral tract (spinotransversal, intertransversal system)

o Musculus Splenius Cervicis

Origin: Spinous process (Th3-Th6)

Insertion: Transverse process (C1-C2)

Function: Dorsal extension (Th1-Th12), lateral flexion, rotation

o Musculus Splenius Capitis

Origin: Spinous process (C3-Th3)

Insertion: Linea nuchalis superior (lateral), mastoid process

Function: Dorsal extension (Th1-Th12), lateral flexion, rotation

o Musculi intertransversarii

Origin: Mammilary processes and costal processes (Lumbar), tuberculae posteriora/anteriora (C2-C7)

Insertion: Mammilary processes and costal processes (Lumbar), tuberculae posteriora/anteriora (C2-C7)

Function:Stabilazation, dorsal extension (Cervical, lumbar), lateral flexion (Cervical, lumbar)

o Musculi levatores costarum breves

Origin: Spinous process (C7-Th11)

Insertion: Angulus costae (One rib lower than the process)

Function: Dorsal extension, ipsilateral flexion, contralateral rotation

o Musculi levatores costarum longi

Origin: Spinous process (C7-Th11)

Insertion: Angulus costae (Two ribs higher than the process)

Function: Dorsal extension, ipsilateral flexion, contralateral rotation

• Medial tract (spinal system)

o Musculi interspinales cervicis

Origin: Spinous processes (Cervical)

Insertion: Spinous processes (Cervical)

Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, lumbar)

o Musculi interspinales lumborum

Origin: Spinous processes (Lumbar)

Insertion: Spinous processes (Lumbar)

Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, lumbar)

o Musculus spinalis thoracis

Origin: Spinous process (Th10-L3)

Insertion: Spinous process (Th2-Th8)

Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, thoracal), lateral flexion

o Musculus spinalis cervicis

Origin: Spinous process (C5-Th2)

Insertion: Spinous process (Th2-Th4)

Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, thoracal), lateral flexion

• Medial tract (transversospinal system)

o Musculi rotatores breves

Origin: Transverse processes (Thoracal)

Insertion: Spinous processes (Thoracal – one spinous process higher than the transverse process)

Function: Dorsal extension (Thoracal), contralateral rotation

o Musculi rotatores longi

Origin: Transverse processes (Thoracal)

Insertion: Spinous processes (Thoracal –two spinous processes higher than the transverse process)

Function: Dorsal extension (Thoracal), contralateral rotation

o Musculus multifidus

Origin: Transverse processes, spinous processes

Insertion: Transverse processes, spinous processes

Function: Dorsal extension, lateral flexion, contralateral rotation

o Musculus semispinalis capitis

Origin: Spinous process (C3-Th6)

Insertion: Os occipitale

Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, thoracal), lateral flexion, contralateral rotation

o Musculus semispinalis thoracis

Origin: Spinous process (Th6-Th12)

Insertion: Spinous process (C6-Th4)

Function: Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, thoracal), lateral flexion, contralateral rotation

o Musculus semispinalis Cervicis

Origin: Spinous process (Th1-Th6)

Insertion: Transverse process (C2-C7)

Function: Function: Dorsal extension (Cervical, thoracal), lateral flexion, contralateral rotation24

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders are because of hormonal influences (progesterone stimulates respiration). Currently, there isn’t a consensus as to the scale of breathing pattern disorders in the general population, but a pilot study35 examined the relationship between BPD and musceloskeletal pain and showed that 75% of those examined showed faulty breathing patterns.

Dysfunctional breathing (DB) is defined as chronic or recurrent changes in breathing pattern that cannot be attributed to a specific medical diagnosis, causing respiratory and non-respiratory complaints.28 (level of evidence: 2). Although interesting, this study has several limitations. It was not designed or intended to be a reliability study. Its methods have no proven reliability. Future research is needed to validate the inter-examiner reliability of the methods of assessing breathing mechanics and the criteria of normal and faulty patterns of respiration. But if this numbers reflect to the general population, there is a 3 in 4 chance that your patient will have faulty breathing patterns.

People with respiratory problems are less able to exercise due to breathing difficulties and are therefore more sedentary than healthy individuals. (Mannino et al. 2003: Level of evidence 2) It is therefore possible that these patients will evolve back pain.12 (level of evidence: 3)

Several studies also point the specific role of a sedentary lifestyle that includes (1) mechanical factors such as prolonged wrong postures leading to wasting and weakness of postural muscles and (2) chronic muscle spasm resulting from psychologic stress in the etiology of chronic low back pain.4 (level of evidence: 1)

Charactersitics/Clinical presentation

[edit | edit source]

Movement is defined as the ability to produce and maintain an adequate balance of mobility and stability along the kinetic chain while integrating fundamental movement patterns with accuracy and efficiency. Postural control deficits, poor balance, altered proprioception, and inefficient motor control have been shown to contribute to pain, disability, and interfere with normal movement. Identification of risk factors that lead to these problems and contribute to dysfunctional movement patterns could aid injury prevention and performance.

Abnormal breathing patterns (noted by George Yuan et al.)

- Thoracoabdominal paradox: this refers to the asynchronous movement of the thorax and abdomen that can be seen with respiratory muscle dysfunction and increased work of breathing. This can be seen as a pure paradox where the thorax and abdomen are moving in opposite directions at the same time.

- Kussmaul’s breathing: this refers to a pattern with regular increased frequency and increased tidal volume and can often be seen to be gasping. Severe metabolic acidosis is often seen.

- Apneustic breathing: this refers to breathing where every inspiration is followed by an prolonged inspiratory pause and each expiration is followed by a prolonged expiratory pause. This expiratory pause is often mistaken for an apnea. The cause is damage to the respiratory center in the upper pons. - Cheyne stokes respiration: this refers to a cyclical crescendo-descrescendo pattern of breathing. This is followed by periods of central apnea. This is often seen in patients with stroke, brain tumor, traumatic brain injury, carbon monoxide poisoning, metabolic encephalopathy, altitude sickness, narcotics use and in non-rapid eye movement sleep of patients with congestive heart failure

- Ataxic and Biot’s breathing: these are forms of breathing that are sometimes lumped together and usually are related to brainstem strokes or narcotic medications. Ataxic breathing refers to breathing with irregular frequency and tidal volume interspersed with unpredictable pauses in breathing of periods of apnea. Biot’s breathing refers to a high frequency and regular tidal volume breathing interspersed with periods of apnea

- Agonal breathing: this refers to a pattern of irregular and sporadic breathing with gasping seen in dying patients before their terminal apnea. This form of breathing is inadequate to sustain life.

There is evidence that the effects of breathing pattern disorders, such as hyperventilation (hyperventilation results in respiratory alkalosis), negatively interfere and influence a variety of psychological, biochemical, neurological and biomechanical factors. Breathing pattern disorders, automatically increase levels of anxiety and apprehension, which may be sufficient to alter motor control and to considerably influence balance control.6 (level of evidence: 2)

Diaphragmatic and transversus abdominis tone are key features in providing the body of core stability, however it has been noted that reduction in the support offered to the spine, by the muscles of the torso, may occur if there is both a load challenge to the low back, combined with a breathing challenge. It has been demonstrated that, after approximately 60 seconds of hypercapneoa, the postural (tonic) and phasic functions of both the diaphragm and transversus abdominis are reduced or absent. Breathing rehabilitation offers the potential for reducing the negative influences resulting from breathing pattern disorder.6 (level of evidence: 2)

Another study suggest that breath therapy may enhance proprioception and, therefore, may be an appropriate complementary intervention particularly for patients with back pain.24

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Abnormal breathing patterns are:

often combined with musculoskeletal disorders. Individuals with poor posture, scapular dyskinesis, neck pain, temporomandibular joint pain and also low back pain exhibit signs of faulty breathing mechanisms.[29]

Over activity of the accessory muscles (sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius, and scalene muscles), whom induces thoracic breathing, have been linked to neck pain, scapular dyskinesis and trigger point formation.[29] Poor coordination of the diaphragm may result in compromised stability of the lumbar spine, altered motor control and dysfunctional movement patterns.[32]

In addition to only checking the influence of a breathing pattern disorder affecting musculoskeletal regions (in this case the lower back), it is necessary to also make the differential diagnosis of what could lead to the low back pain besides the BPD.

Low back pain is typically classified as being ‘specific’ or ‘non-specific’. Specific low back pain is defined as symptoms caused by specific patho-physiological mechanism, such as:

- hernia

- nuclei pulposi

- infection

- inflammation

- osteoporosis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- fracture

- tumour

Non-Specific low back pain is defined as symptoms without clear specific cause, i.e. low back pain of unknown origin. Approximately 90% of all low back pain patients will have non-specific low back pain. Nowadays there still don’t exist a reliable and valid classification system for the large majority of non-specific low back pain. The most important symptoms are pain and disability.

People suffering from chronic low back pain have other associated problems such as anxiety, depression, and disability, with a reduced quality of life. Rates of major depression are 20% for persons with chronic back pain, compared to 6% for pain-free individuals.5 (level of evidence: 2)

[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnostic procedure for low back pain is mainly focused on the triage of patients with specific or non-specific low back. The triage is used to exclude specific pathology and nerve root pain.36 Actually you can see breathing therapy as an additional therapy, but not as the main goal of your therapy.37

There are characteristics for recognizing and diagnosing breathing pattern disorders:38

• Restlessness (type A, “neurotic”)

• ‘Air hunger’

• Frequent sighing

• Rapid swallowing rate

• Poor breath-holding times

• Poor lateral expansion of lower thorax on inhalation

• Rise of shoulders on inhalation

• Visible “cord-like” sternomastoid muscles

• Rapid breathing rate

• Obvious paradoxical breathing

• Positive Nijmegen Test score (23 or higher)

• Low end-tidal CO2 levels on capnography assessment (below 35mmHg)

• Reports of a cluster of symptoms such as fatigue, pain (particularly chest, back and neck), anxiety, ‘brain-fog’, irritable bowel or bladder, paresthesia, cold extremities.

If a patient has low back pain in combination with one of these characteristics, breathing therapy is advised.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

A 10 cm VAS can be used to assess pain intensity, this has to be assesses at baseline, further into the therapy and after the therapy.

The Roland Morris Scale (24-item) to assess low back pain-specific functional disability.

In a randomized controlled trial by Mehling a modified 16-item Roland Morris Scale was used and transformed to the 24-item score equivalent for comparison purposes.

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) measures functional overall health status. (NL)

The measurement of postural stability at baseline and immediately after therapy can provide a surrogate measure for whole-body proprioception and body awareness. This can be done with computerized dynamic posturography or with a traditional static force plate on which patients stand on a force platform and attempt to maintain balance while standing in a neutral position. Patients can then be assessed on their ability to integrate visual, vestibular and proprioceptive components of balance (eyes closed, static vs compliant platform, static or moving surround visuals,...). This outcome is referred to as the Equilibrium Score (ES). (Mehling et al.).25 (level of evidence: 2)

Examination[edit | edit source]

Symptoms of BPD can be:

• Dizziness

• Chest pain

• Altered vision

• Feelings of depersonalization and panic attacks

• Nausea

• Reflux

• General fatigue

• Concentration difficulties

• neurological/psychological/gastro-intestinal and musculoskeletal changes can occur

• dyspnoea with normal lung function

• deep sighing

• exercise induced breathlessness

• frequent yawning

• hyperventilation

BPD is diagnosed using physical assessment, a validated questionnaire (the Nijmegen) and a capnometer (measures respiratory Co2 levels)

• The Nijmegen questionnaire provides a non- invasive test of high sensitivity (up to 91%) and specificity (up to 95%).This easily administered, internationally validated diagnostic questionnaire is the simplest, kindest and to date most accurate indicator of acute and chronic hyperventilation. The questions enquire as to the following symptoms, and their intensity6 (level of evidence 2):

• Constriction in the chest (the feeling of tightness in the chest)

• shortness of breath, accelerated or deepened breathing, inability to breathe deeply, feeling tense, tightness around the mouth, stiffness in the fingers or arms, cold hands or feet,

• tingling fingers,

• bloated abdominal sensation

• dizzy spells,

• blurred vision

• feeling of confusion or losing touch with environment.

• Capnography have been shown to have a good concurrent validity when compared to arterial CO2 measures and can provide acces to this very important physiological information39

Because previous studies of breathing therapy have not included capnography in their research, it’s difficult to say anything about the validity of the device in function of therapy 40

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Low back pain

The most commonly prescribed medications for low back pain are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), skeletal muscle relaxants, and opioid analgesics.

The chosen review is part of a larger evidence review commissioned by the American Pain Society and the American College of Physicians to guide recommendations for management of low back pain.7 (level of evidence: 1)

In summary, this review shows that several medications evaluated in this report are effective for short-term relief of acute or chronic low back pain, although each is associated with a unique set of risks and benefits. There is evidence that NSAIDs, skeletal muscle relaxants (for acute low back pain), and tricyclic antidepressants (for chronic low back pain) are effective for short-term relief.7 (level of evidence: 1). For mild or moderate pain, a trial of acetaminophen might be a reasonable option because it may offer a more favorable safety profile than NSAIDs, that is used for more severe pain. For very severe, disabling pain, a trial of opioids may be an option to achieve adequate pain relief and improve function, despite some potential risks.9 (level of evidence: 3). For all medications included in this review, evidence of beneficial effects on functional outcomes is limited and further research is required.7 (level of evidence: 1)

When there is a matter of low back pain due to a disc herniation, spondylolisthesis or spinal stenosis choosing a surgery is an adequate possibility. In a large follow-up study with patients with spondylolisthesis and associated spinal stenosis, one group received a surgical treatment and the other group a non-surgical treatment. Results of this study report that the group that was treated surgically maintains substantially greater pain relief and improvement in function for four years.9 (level of evidence: 3). In another study where they focused on patients with disc herniation, the study concluded that after 4 years, patients who underwent surgery for a lumbar disc herniation achieved greater improvement than those treated non-operatively.10 (level of evidence: 1)

Breathing pattern disorders

The most frequently used drug for treatment of asthma in children and adults are the beta-agonists. These agonists are the most potent bronchodilators available. Using these bronchodilators helps increase the airway caliber and suppress the inflammation and causes quick relief of symptoms of asthma. The beta-agonists are taken by inhalation, because inhalation is preferable to other routes because of the better dose effect ratio and the quicker effect.19 (level of evidence: 4)

Another study has determined if deterioration could be slowed in patients with asthma of COPD during bronchodilator therapy by a treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid. The study was a 4 year prospective study where during the first 2 year of treatment, the patients were given only bronchodilator therapy and during the last two years additional treatment with corticosteroid. This study showed that adding corticosteroid to the treatment, slowed the unfavorable course of asthma or COPD. In asthmatic patients, this effect was most evident.20 (level of evidence: 2)

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Breathing rehabilitation offers the potential for reducing the negative influences resulting from breathing pattern disorders.5 (level of evidence: 2)

The particular quality of breath therapy in low back pain patients is that the patients learn to focus on the subtle sensations of breath as it moves the inner physical space of those body areas where patients would rather not want to focus on. Patients generally want to get away from pain and invest considerable effort into avoiding the perception of painful areas. Moreover, low back pain seems to develop particularly in those neglected areas of the body, where patients have the greatest difficulty and the least practice in focusing on the perception of autonomous non-manipulated breath movements. Through verbal guidance and skilled touch, breath therapists help in the development of the patients’ skill to allow and fully experience such autonomous breath movements within the area of pain.7 (level of evidence: 1)

The results of this descriptive study suggest that breath therapy may enhance proprioception and, therefore, may be an appropriate complementary intervention particularly for patients with back pain.7 (level of evidence: 1)

If clinical research can demonstrate a therapeutic effect of breath therapy on patients with back pain, we might discover breath therapy to be a therapeutic method which works directly at the interface of physical and psychological processes. The experience of breath as a therapeutic intervention might be an essential step toward an integrative medicine.7 (level of evidence: 1)

GUIDELINE:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rachel_Garrod/publication/24393894_British_Thoracic_Society_Physiotherapy_guideline_development_Group_Guidelines_for_the_physiotherapy_management_of_the_adultmedicalspontaneously_breathing_patients/links/0912f51484ec2790c1000000.pdf

BREATHING DISORDERS

Patients who suffer from respiratory problems may be treated by physiotherapists. This treatment tries to manage the breathlessness, to control the symptoms, to improve or maintain the mobility and function, to clear the airway and cough enhancement or support.

Techniques could be:

• Exercise testing

• Exercise prescription

• Airway clearance

• Position techniques

• Breathing techniques

Physiotherapy can also be helpful for musculoskeletal or/and postural dysfunction and pain and improving continence during coughing and forced expiratory maneuvers. Physiotherapist can offer pulmonary rehabilitation and can be non-invasive.21 (level of evidence: 2)

The basic principles are common in the most physiotherapy treatment protocols15 (level of evidence:4)

1) Education on the pathophysiology of the disorder

2) Self-observation of one’s own breathing pattern

3) Restoration to a, personally adapted, basic physiological breathing pattern: relaxed, rhythmical nose–abdominal breathing.

4) Appropriate tidal volume

5) Education of stress and tension in the body

6) Posture

7) Breathing with movement and activity

8) Clothing Awareness

9) Breathing and speech

10) Breathing and nutrition

11) Breathing and sleep

12) Breathing through an acute episode

The effectiveness of physiotherapy on patients with asthma has been studied in a randomised clinical trial. Asthma is a functional breathing disorder and this study shows a clinical relevant improvement in quality of life following a short physiotherapy intervention.22 (level of evidence: 1)

THERAPY

Studies have shown that eight weeks inspiratory muscle training in individuals with LRP to a training resistance of 60% of the 1RM leads to a significant improvement in inspiratory muscle strength, a more multi-segmental postural control strategy, increased inspiratory muscle strength and decrease of LBP severity.44 [25

According to following article of Wolf E. Mehling et al, examined the effect of breathing therapy on low back pain. However changes in pain and disability were comparable to those resulting from extended physical therapy. They compared the effects of breathing therapy with the effect of physical therapy. Each group received one introductory evaluation sessions of 60 minutes and 12 individual therapy sessions of equal duration, 45 minutes over 6 to eight weeks. The breath therapy was given by 5 certified breath therapists. Physical therapy was given by experienced physical therapy faculty members in the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science.45

The 90/90 bridge with ball and balloon technique was designed to help restore the ZOA (Zone of Apposition) and spine to a proper position in order to allow the diaphragm optimal ability to perform both its respiratory and postural roles. It's a therapeutic exercise that promotes optimal posture and neuromuscular control of the deep abdominals, diaphragm, and pelvic floor would be desirable for patients with breathing disorders en patients with LBP. The balloon blowing exercise (BBE) technique is performed in supine with the feet on a wall, hips and knees at 90 degrees and a ball between the knees. This passive 90˚ hip and knee flexion position places the body in relative lumbar spine flexion, posterior pelvic tilt and rib internal rotation/depression which serves to optimize the ZOA

and discourage lumbar extension/anterior pelvic.44

Studies of the effects of a single BBE and/or training effects of multiple BBE’s could include EMG for abdominal muscle, spirometry for changes in breathing parameters, real time ultrasound for diaphragm length and/or changes in abdominal muscle thickness. Additionally, future studies designed to describe changes in pain and function attributable to the BBE are needed to investigate the clinical efficacy of this promising therapeutic exercise technique.[28

According to following article, Laurie McLaughlin et al, breathing retraining should improve end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), pain and function in most patients complaining of neck or back pain.

Poor breathing profiles were found in patients with neck or back pain: high respiratory rate, low CO2, erratic non-rhythmic patterns and upper chest breathing.

Exercises

According to the article by Laurie McLaughlin et al, breathing retraining should improve end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2), pain and function in most patients complaining of neck or back pain.14

Abdominal Breathing Technique:

How it’s done: With one hand on the chest and the other on the belly, take a deep breath in through the nose, ensuring the diaphragm (not the chest) inflates with enough air to create a stretch in the lungs. The goal: Six to 10 deep, slow breaths per minute for 10 minutes each day to experience immediate reductions to heart rate and blood pressure34 37

The three-part breath:

The patiënt lies down on the back with the eyes closed, relaxing the face and the body. Then begin to inhale deeply through the nose. On each inhale, fill the belly up with your breath. Expand the belly with air like a balloon. On each exhale, expel all the air out from the belly through your nose. Draw the navel back towards your spine to make sure that the belly is empty of air.14

On the next inhale, fill the belly up with air as described before. Then when the belly is full, draw in a little more breath and let that air expand into the rib cage causing the ribs to widen apart. with the exhale, let the air go first from the rib cage, letting the ribs slide closer together, and them from the belly, drawing the navel back towards the spine. On the next inhale, fill the belly and rib cage up with air as described above. Then draw in just a little more air and let it fill the upper chest. On the exhale, let the breath go first from the upper chest, then from the rib cage, letting the ribs slide closer together. Finally, let the air go from the belly, drawing the navel back towards the spine.37 34

Breathing excercises in combination with strenght training:

The following excercises39 are performed with a powerbreathe KH1 device. This handheld device applies a variable resistance provided by an electronically controlled valve (variable flow resistive load). Loading is maintained at the same relative intensity throughout the breath, by reducing the absolute load to accommodate the pressure–volume rela- tionship of the inspiratory muscles. The application of a tapered load allows patients to get close to maximal inspiration, even at high-training intensities.

Performing excercises for training the backmuscles in combination with this device can increase the muscle strength of the inspiratory muscles and also the muscles of the back.38

Excercise 139

Stand on one leg with the device in the mouth and with one arm extended above you holding the resistance ( cable machine or resistance band).

Make sure that you have a straight body line between your ankle and shoulders, that you have a neutral spine and that your abdominal corset muscles are braced. Flex forward, rotating at the hip and inhale forcefully through the device. Exhale as you retrn to the upright start position. You can swap breathing phases between sets

You can make tis excercise more dificult by using more weight at the cable machine. You can also increase the resistance of the device.

2 sets with 15 repetitions.

Excercise 239

Begin with your feet shoulder width apart and with the device in the mouth. Hold the resistance (cable cord or resistance band) in one hand, with your hand near your shoulder.<o:p></o:p>

Make sure you have a neutral spine and brace your abdominal corset muscles.<o:p></o:p>

Press the handle of the cable away from you., lunging forward. As you move forward, inhale forcefullu through the device and exhale when you return back to the upright start position. You can swap breathing phases between sets. <o:p></o:p>

You can make tis excercise more dificult by using more weight at the cable machine. You can also increase the resistance of the device.

2 sets with 15 repititions.

Excercise 339

Begin with a lean position on your toes and on your arms. Hold your hands together. Hold the divice in your mouth.

Make sure you have a neutral spine and brace your abdominal corset muscles.

Hold this position for 30 seconds while you breath through the device.

You can make this excercise more dificult by bringing one leg to your body and return it afterwards. You repeat this with the other leg during the excercise.

You can also increase the resistance of the device.

3 sets

Excercise 439

Lie down on your back and keep your arms at your sides. Hold the device in your mouth. Lift your hips towards the ceiling while you make sure that you brace the abdominal corset muscles. Also make sure you keep your knees and thighs parallel. Hold this for 30 seconds while you breath through the device.

You can make this excercise more dificult by raising one leg during the excercise and bring it back to the ground. you can do this alternating with the other leg.

You can also increase the resitance of the device.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

One level 1B RCT [3] studied the effects of breathing therapy on chronic low back patients. Patients improved significantly with breathing therapy. The changes in standard low back pain measures of pain and disability were comparable to those resulting from high-quality, extended physical therapy

There is also a review that describes the relationship between low back pain and breathing pattern disorders[4]. The review states that there is evidence of a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between low back pain and respiratory problems. All the studies in this review were cross sectional 2A level cohort studies.

In one case serie [5] of 24 patient with low back or pelvic pain, they all showed an altered respiratory chemistry. Breathing dramatically improved with breathing retraining (all but one reached normal ETCO2 values). 75% of the patients reported improvements in pain, 50% reported improvements in functional activity. These results were both clinically important and statistically significant.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Janssens L, Brumagne S, Polspoel K, Troosters T, McConnell A. The effect of inspiratory muscles fatigue on postural control in people with and without recurrent low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 May 1;35(10):1088-94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bee5c3.

Janssens L, Brumagne S, McConnell AK, Hermans G, Troosters T, Gayan-Ramirez G. Greater diaphragm fatigability in individuals with recurrent low back pain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013 Aug 15;188(2):119-23. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.028. Epub 2013 May 31.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Breath therapy would provide a short-term improvement in pain and related functional limitations, but in the longer term one has to deal with a major downturn which it is not significantly better than conservative physiotherapy. Other research has shown that yoga is more effective than a self-care book, but there is only weak evidence that it is more effective than physical exercises.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1-UFW4KkLsPjVlBi3wM7t-SugMHpfpN_BxFjjpTPdh2a4sKsAe|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ B.R. Johnson, W.C. Ober, C.W. Garrison, A.C. Silverthorn. Human Physiology, an integrated approach, Fifth edition. Dee Unglaub Silverthorn, Ph.D.

- ↑ Theodore A. Wilson and Andre De Troyer. diaphragm Diagrammatic analysis of the respiratory action of the. J Appl Physiol 108:251-255, 2010. First published 25 November 2009; doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00960.2009(A1)

- ↑ Mehling WE, Hamel KA, Acree M, Byl N, Hecht FM. Randomized, controlled trial of breath therapy for patients with chronic low-back pain, Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2005 Jul-Aug;11(4):44-52 (1B)

- ↑ Lise Hestbaek, DC,a Charlotte Leboeuf-Yde, DC, MPH, PhD,b and Claus Manniche, DrMedScc . IS LOW BACK PAIN PART OF A GENERAL HEALTH PATTERN OR s IT A SEPARATE AND DISTINCTIVE ENTITY?A CRITICAL LITERATURE REVIEW OF COMORBIDITY WITH LOW BACK PAIN. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 May;26(4):243-52. (2A)

- ↑ Laurie McLaughlin, Charlie H. Goldsmith, Kimberly Coleman. Breathing evaluation and retraining as an adjunct to manual therapy. Manual therapy, volume 16, Issue 1, pages 51-52 (3B)