Lateral Collateral Ligament of the Knee: Difference between revisions

m (moved LCL Test to Lateral Collateral Ligament) |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Category:Anatomy - Knee" to "") |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Dorien Scheirs|Dorien Scheirs]], [[User:Joris De Pot|Joris De Pot]] | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Dorien Scheirs|Dorien Scheirs]], [[User:Joris De Pot|Joris De Pot]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

< | == Description == | ||

The fibular or lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a cord-like band and acts as the primary varus stabilizer of the knee.<ref name=":0">LaPrade, R. F., Macalena, J. A. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309550053_Fibular_Collateral_Ligament_and_the_Posterolateral_Corner Fibular collateral ligament and the posterolateral corner.] Insall & Scott Surgery of the Knee. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2012; 45: 592-607. | |||

</ref> It is one of 4 critical ligaments involved in stabilizing the [[Knee|knee joint.]] | |||

== | === Anatomy === | ||

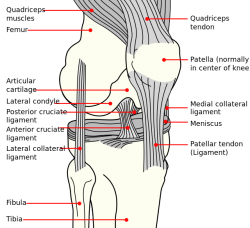

[[Image:Knee ligaments.png|250x250px|lateral collateral ligament|right|frameless]]'''Origin''': Lateral epicondyle of the [[femur]] | |||

'''Insertion''': Fibula head | |||

== | <ref name="two">Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Prometheus deel 1: Algemene anatomie en bewegingsapparaat. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, 2005.</ref><ref name="nine">Whiting WC, Zernicke RF. Biomechanics of musculoskeletal injury. 2nd ed. Human Kinetics, 2008.</ref> | ||

The lateral | At the proximal level this ligament is closely related to the joint capsule, without having direct contact, as it is separated by fat pad, The insertion is augmented by the [[Iliotibial Band Syndrome|iliotibial band]].<ref name=":1">Malagelada F, Vega J, Golano P, Beynnon B, Ertem F. Knee Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Knee. In: DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 4th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014. | ||

</ref> The [[Popliteus Muscle|popliteus]] tendon is deep to the LCL, seperating it from the [[lateral meniscus]].<ref name=":3">Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinial oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2010.</ref> The LCL further splits the [[Biceps Femoris|biceps femoris]] into two parts.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

== Function == | |||

The LCL stabilizes the lateral side of the knee joint, mainly in varus stress and posterolateral rotation of the tibia relative to the femur. The LCL acts as a secondary stabilizer to anterior and posterior tibial translation when the cruciate ligaments are torn. <ref name=":0" /> | |||

It is primary restraint to varus rotation from 0-30° of knee flexion. As the knee goes into flexion, the LCL loses its significance and influence as a varus-stabilizing structure.<ref name=":2">Miller RH, Azar FM. Knee injuries. In: Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2016; 2121-2297. | |||

</ref> When the knee is extended, the LCL is stretched. | |||

== Clinical relevance == | |||

The incidence of [[Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee|LCL injuries]] are relatively low (6%) when compared to other knee injuries.<ref>Tandeter HB., Shvartzman, P. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10605994 Acute knee injuries: use of decision rules for selective radiograph ordering.] Am Fam Physician 1999; 60(9): 2599-2608.</ref> It is commonly associated with other knee ligament injuries, thus LCL tear can be easily overlooked as a result of that.<ref>Kane PW et al. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29884567 Increased Accuracy of Varus Stress Radiographs Versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Diagnosing Fibular Collateral Ligament Grade III Tears.] Arthroscopy, 2018. | |||

</ref> | |||

'''Mechanism of injury:''' (for more information, see the page on [[Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee|LCL injuries]])<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* A direct blow to the anteromedial knee and posterolateral corner | |||

* Non-contact hyperextension | |||

* Non-contact varus stress<ref name=":1" /> | |||

== Assessment == | |||

=== Palpation === | |||

Patient position: Legs crossed with ankle resting on opposite knee (90° knee flexion, hip abduction and external rotation) | |||

In this position the iliotibial band relaxes and makes the LCL easier to isolate. The ligament lies laterally and posteriorly along the joint line. Ocassionally, the LCL is congenitally absent. <ref>Hoppenfeld S, Hutton R, Hugh T. Physical examination of the spine and extremities. 1st ed. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1976.</ref> When LCL is injured or torn, this cordlike band is not as noticeable as on the unaffected side. | |||

=== Special tests === | |||

'''Adduction (varus) stress test''' | |||

''Purpose:'' The varus stress test shows a lateral joint line gap. | |||

''Performance:'' A varus stress test is performed by stabilizing the femur and palpating the lateral joint line. The other hand provides a varus stress to the ankle. The test is performed at 0° and 20-30°, so the knee joint is in the closed packed position. The physiotherapist stabilize the knee with one hand, while the other hand adducts the ankle.<ref name=":4">Petty NJ. Neuromusculoskeletal examination assessment: A handbook for therapists. 3rd edition. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006.</ref> | |||

''Interpretation:'' If the knee joint adducts greater than normal (compared to the unaffected leg), the test is positive. This an indication of a LCL tear. | |||

''Other structures involved:''<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* 0°: Posteriolateral capsule, arcuate-popliteus complex, anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, lateral gastrocnemius | |||

* 20-30°: Posteriolateral capsule, arcuate-popliteus complex, iliotibial band, biceps femoris tendon | |||

''Reliability and validity:'' | |||

* Sensitivity: 25%. Specificity: not reported. Varus stress testing was performed in 20° of flexion, and testing in extension was not done.<ref>Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, McLean J. [https://www.archives-pmr.org/article/S0003-9993%2802%2904844-X/pdf Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests.] Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2003; 84(4): 592-603.</ref> | |||

* Sensitivity: 25% . The reliability of this test in extension is 68% and in 30° flexion only 56%. The test is fairly solid.<ref>Merriman L, Turner W. Assessment of the Lower Limb. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone, 2002.</ref> | |||

* If the varus stress test is positive at 20°, but negative at 0°, only the LCL is torn. A positive result at both 0° and 20° indicate cruciate ligament involvement.<ref>Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.</ref> | |||

<clinicallyrelevant id="84562015" title="Varus stress test" /> | |||

< | '''Additional tests for detecting LCL injury with other knee ligaments:'''<ref name=":2" /> | ||

* External Rotation-Recurvatum Test | |||

* Reverse Pivot Shift Sign of Jakob, Hassler, and Stäubli | |||

* [[Dial Test]] | |||

== | == Resources == | ||

* [[Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee|Lateral collateral ligament injuries]] | |||

== References == | |||

== References | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/ | [[Category:Knee - Anatomy]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category:Sports_Injuries]][[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Knee]] [[Category:Assessment]] [[Category:Ligaments]] [[Category:Knee - Ligaments]] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:04, 29 August 2019

Original Editors - Dorien Scheirs, Joris De Pot

Top Contributors - Saimat Lachinova, Admin, Joris De Pot, Dorien Scheirs, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Leana Louw, Oyemi Sillo, WikiSysop, Tony Lowe, Derycker Andries, Naomi O'Reilly, George Prudden and Kai A. Sigel

Description[edit | edit source]

The fibular or lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a cord-like band and acts as the primary varus stabilizer of the knee.[1] It is one of 4 critical ligaments involved in stabilizing the knee joint.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Origin: Lateral epicondyle of the femur

Insertion: Fibula head

At the proximal level this ligament is closely related to the joint capsule, without having direct contact, as it is separated by fat pad, The insertion is augmented by the iliotibial band.[4] The popliteus tendon is deep to the LCL, seperating it from the lateral meniscus.[5] The LCL further splits the biceps femoris into two parts.[5]

Function[edit | edit source]

The LCL stabilizes the lateral side of the knee joint, mainly in varus stress and posterolateral rotation of the tibia relative to the femur. The LCL acts as a secondary stabilizer to anterior and posterior tibial translation when the cruciate ligaments are torn. [1]

It is primary restraint to varus rotation from 0-30° of knee flexion. As the knee goes into flexion, the LCL loses its significance and influence as a varus-stabilizing structure.[6] When the knee is extended, the LCL is stretched.

Clinical relevance[edit | edit source]

The incidence of LCL injuries are relatively low (6%) when compared to other knee injuries.[7] It is commonly associated with other knee ligament injuries, thus LCL tear can be easily overlooked as a result of that.[8]

Mechanism of injury: (for more information, see the page on LCL injuries)[4]

- A direct blow to the anteromedial knee and posterolateral corner

- Non-contact hyperextension

- Non-contact varus stress[4]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Patient position: Legs crossed with ankle resting on opposite knee (90° knee flexion, hip abduction and external rotation)

In this position the iliotibial band relaxes and makes the LCL easier to isolate. The ligament lies laterally and posteriorly along the joint line. Ocassionally, the LCL is congenitally absent. [9] When LCL is injured or torn, this cordlike band is not as noticeable as on the unaffected side.

Special tests[edit | edit source]

Adduction (varus) stress test

Purpose: The varus stress test shows a lateral joint line gap.

Performance: A varus stress test is performed by stabilizing the femur and palpating the lateral joint line. The other hand provides a varus stress to the ankle. The test is performed at 0° and 20-30°, so the knee joint is in the closed packed position. The physiotherapist stabilize the knee with one hand, while the other hand adducts the ankle.[10]

Interpretation: If the knee joint adducts greater than normal (compared to the unaffected leg), the test is positive. This an indication of a LCL tear.

Other structures involved:[10]

- 0°: Posteriolateral capsule, arcuate-popliteus complex, anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, lateral gastrocnemius

- 20-30°: Posteriolateral capsule, arcuate-popliteus complex, iliotibial band, biceps femoris tendon

Reliability and validity:

- Sensitivity: 25%. Specificity: not reported. Varus stress testing was performed in 20° of flexion, and testing in extension was not done.[11]

- Sensitivity: 25% . The reliability of this test in extension is 68% and in 30° flexion only 56%. The test is fairly solid.[12]

- If the varus stress test is positive at 20°, but negative at 0°, only the LCL is torn. A positive result at both 0° and 20° indicate cruciate ligament involvement.[13]

Varus stress test video provided by Clinically Relevant

Additional tests for detecting LCL injury with other knee ligaments:[6]

- External Rotation-Recurvatum Test

- Reverse Pivot Shift Sign of Jakob, Hassler, and Stäubli

- Dial Test

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 LaPrade, R. F., Macalena, J. A. Fibular collateral ligament and the posterolateral corner. Insall & Scott Surgery of the Knee. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2012; 45: 592-607.

- ↑ Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Prometheus deel 1: Algemene anatomie en bewegingsapparaat. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, 2005.

- ↑ Whiting WC, Zernicke RF. Biomechanics of musculoskeletal injury. 2nd ed. Human Kinetics, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Malagelada F, Vega J, Golano P, Beynnon B, Ertem F. Knee Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Knee. In: DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 4th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinial oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Miller RH, Azar FM. Knee injuries. In: Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2016; 2121-2297.

- ↑ Tandeter HB., Shvartzman, P. Acute knee injuries: use of decision rules for selective radiograph ordering. Am Fam Physician 1999; 60(9): 2599-2608.

- ↑ Kane PW et al. Increased Accuracy of Varus Stress Radiographs Versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Diagnosing Fibular Collateral Ligament Grade III Tears. Arthroscopy, 2018.

- ↑ Hoppenfeld S, Hutton R, Hugh T. Physical examination of the spine and extremities. 1st ed. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1976.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Petty NJ. Neuromusculoskeletal examination assessment: A handbook for therapists. 3rd edition. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006.

- ↑ Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, McLean J. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2003; 84(4): 592-603.

- ↑ Merriman L, Turner W. Assessment of the Lower Limb. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

- ↑ Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.