Kienbock's Disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

On physical inspection, the range of motion is quite sensitive, especially when extending the wrist. Movements such as flexion and extension are shrunken, sometimes combined with a progressively loss of grip strength.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":7" /> However, the rotation of the forearm is still maintained. | On physical inspection, the range of motion is quite sensitive, especially when extending the wrist. Movements such as flexion and extension are shrunken, sometimes combined with a progressively loss of grip strength.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":7" /> However, the rotation of the forearm is still maintained. | ||

= | = Management = | ||

The | The goal of treating Kienböck disease is pain relief, wrist motion preservation, and preservation of grip strength. | ||

Treatment of Kienböck disease depends on the stage of the disease and its causative factors. Stage I is always treated with splinting or cast immobilization. Stage II can also be treated with immobilization if necrosis is incomplete. Stages II with complete necrosis, III, and IV require "joint-leveling" surgery possibly coupled with vascular bone grafting or transfer of branches from adjacent arteries. Later stages with lunate collapse and secondary wrist degenerative arthrosis may also require proximal row carpectomy or intercarpal arthrodesis. Radial shortening osteotomy is the most common procedure performed to unload the lunate in cases with coexistent ulnar negative variance. Treatment may improve symptoms and functionality without affecting imaging findings in the advanced stages.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

= Physical Therapy Management = | = Physical Therapy Management = | ||

| Line 194: | Line 121: | ||

It is clear that there are too few studies about physical management of this condition. | It is clear that there are too few studies about physical management of this condition. | ||

= | = Prognosis = | ||

Kienbock disease is invariably progressive, and joint destruction occurs within 3-5 years of onset. | |||

Prognosis depends on: | |||

# Functional Staging: The greater the extent of viable bone, the better the prognosis.[6] | |||

# Negative ulnar variance: The greater the negative variance, the more severe the disease and the more likely it is to progress. | |||

# Age at diagnosis: Patients diagnosed at an older age are more likely to have advanced stage disease and are more likely to progress. | |||

= | It is significant to note that the severity of symptoms does not always correlate with morphologic stage.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

= References = | = References = | ||

Revision as of 02:22, 1 October 2021

Original Editors - Fien Selderslaghs, Mirabella Smolders, Liese Magnus, Laura Van Der Perren and Jessica Worrell

Top Contributors - Jessica Worrell, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Naomi O'Reilly, Shreya Pavaskar, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami and Evan Thomas

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Kienböck disease refers to avascular necrosis of the lunate carpal bone, known as lunatomalacia.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The proximal carpal row of the mid-carpal joint is largely responsible for wrist motion, as opposed to the relatively fixed distal carpal row. The lunate is the central bone in the proximal row, and it articulates with the scaphoid, capitate, triquetrum, and occasionally the hamate. More proximally, the lunate is a component of the radiocarpal joint, and it also articulates with the ulna via the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). Of note, nearly 10% of the axial-radial/ulnar/carpal load is transmitted through the TFCC and subsequently to the ulna, and 35% through the radiolunate articulation[1]

Image 1: Lunate bone L hand

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Kienböck disease is the second most common type of avascular necrosis of the carpal bones, preceded only by avascular necrosis of the scaphoid.[1]

The age distribution for Kienböck disease depends on gender. The condition is most common within the dominant wrist of young adult men where it appears to be due to repeated loading of the lunate. In women, Kienböck disease typically occurs in middle age and is equally divided between the dominant and non-dominant wrist.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There is a significant association between negative ulnar variance and Kienbock disease, although the majority of people with negative ulnar variance do not have the condition. Ulna variance refers to a disproportionately shortened ulna when compared to the radius. As deduced from the previous section, a shortened ulna results in excessive mechanical stress and repetitive microtrauma exerted on the lunate by the relatively long radius.[1] A causal association is difficult to prove, however, the effectiveness of decompressive procedures such as radial shortening or ulnar lengthening in relieving pain and preventing further collapse of the lunate is supportive. Overall, the negative ulnar variance is present as a predisposing factor in around 75% of cases of Kienbock disease[2].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typical symptoms of Kienböck’s disease are activity-related dorsal wrist pain and weakness, often accompanied by swelling dorsally around the lunate. The complaints are in most cases longstanding and increase progressively. The pain can be described from just mild and occasional to severe and debilitating. The range of motion of the joint is nearly always decreased, with loss of flexion and extension. Compared to the unaffected side there is loss of grip strength.[3] Symptoms are most commonly in the dominant wrist and a history of trauma may be present.[4]

The length of the two bones of the forearm, in particular the ulna and the radius, is not usually equally. We can make a subdivision among the length between the distal articular surfaces of the radius and ulna, called the ulnar variance. It may be negative, positive or neutral. Negative ulnar variance indicates that the distal articular surface of the ulna is located more proximally than the radius, positive ulnar variance indicates the stage where the distal articular surface of the ulna is located more distally compared with the surface of the radius and at last neutral ulnar variance means that the ulnar and radial surfaces are at the same level.[5]

According to Lichtmann et al, the Kienböck’s disease can be subdivided into four stages:[6]

| Stage I | May be perceived by radiographic and CT findings that the density and the contour of the lunate bone is quite normal, but according to the MRI findings there can be noticed that some edema can appear in the bone narrow.[6] |

| Stage II | Characterized by compression of the lunate bone, without some significant modification of its contour.[7] This is associated with increased bone density and debilitation of the lunate on radiographic and CT scans.[6] |

| Stage III | Is the most common stage and is identified as a disruption of the lunate,[7] without radiocarpal or midcarpal degenerative arthritis.[6] The third stage can be subdivided in three subcategories:

Stage IIIA and IIIB are difficult to distinguish. It can be categorized by the radioscaphoid angle. If the angle is less than 60°, it can be classified as stage IIIA. If it exceeds 60°, it’s classified as stage IIIB.[7] |

| Stage IV | Stage IV is comparable with stage III. It is characterized by disruption of the lunate and also associated with radiocarpal or midcarpal degenerative arthritis.[6] |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Radiologic imaging, such as MRI and CT-scans, in case of Kienböck’s disease is generally the only way to give a correct diagnosis.[8] Nonetheless, the radiological findings within the lunate bone of Kienböck’s are often very similar to other pathological conditions, which leads to a common misinterpretation.[6] All of the following pseudo lesions are compared to the different stages of this disorder:

1. Lunate Bone Contusion/Acute Fracture

This type of lesion can hardly be differentiated from stage I Kienböck’s Disease. Having a history of acute episodes of severe trauma to the hand is probably the only characteristic of acute lunate bone fracture that can be separated from Kienböck’s.[6]

2. Ulnocarpal Impaction Syndrome

Chronic impaction between the ulnar head, the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) and the ulnar carpus results in a degenerative pathological condition. Kienböck’s can be differentiated from the Ulnocarpal Impaction Syndrome when there is a bone edema distribution in the ulnar side of the lunate bone, as well as a positive ulnar variance alongside degenerative lesions in the triangular fibrocartilage complex.[6]

3. Infantile and Juvenile Lunatomalacia

This type of Lunatomalacia is acknowledged as the children version of Kienböck’s disease. The only differentiation between these types depends on the age of the patient. Up to 12 years old is called infantile, whereas juvenile affects 13 years and older until skeletal maturity. Pass that point it is called Kienböck’s disease.[6]

4. Arthritis

All sorts of arthritis (rheumatoid, gout, degenerative and post-traumatic) can be compared to the early stages of Kienböck’s. It damages the lunate bone marrow intensity, which can lead to misdiagnosis. However, arthritis has on the one hand both a different clinical presentation and demographic characteristics and default negative ulnar variance on the other.[6][9]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic procedures form the basis for staging, treatment and evaluation of the outcomes.[7] Kienböck’s disease can be diagnosed by evaluating the wrist, along with analyzing the symptoms or any recent injury near the area. Swelling, pain and reduced wrist range of motion are frequent indicators.[8] However, hyperattenuation, density and the degree of the lunate bone collapse are the most important criteria for imaging.[6] A specialist often takes an X-ray of the wrist, in order to gather detailed information and to prevent misdiagnosis. There are many methods to determine Kienböck’s:[6]

- Radiography: Is extremely sensitive and also the most common imaging technique for diagnosing the disease. Plain radiograph can eliminate other pseudo-Kienböck lesions such as fractures and arthritis[6]

- Tomograms: used to determine the extent of the disease

- Bone Scans: help to exclude the presence of Kienböck disease but it is not specific enough to exclude the many other causes of increased uptake in the area of the lunate[4]

- CT-scan: Is claimed to be better and a more specific test than radiographs. This technique is practiced on the late stages of the disease

- MRI: Is declared to be the best imaging technique for Kienböck’s. It is extremely sensitive and specific to detect osteonecrosis.[10] MRI is most significant in the early stages of the disease (particularly in stage I, when the plain radiographs show a rather normal outcome).[6][7]

According to a source, none of these methods were compared to each other. There was additionally no determination to which technique was more accurate. A frequently used staging system for determining radiographic imaging is called “The Stahl classification of Kienbock disease”, which will be discussed below.[6]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Range of motion[11][12][13]

- Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire[14][11][12]

- Grip Strength[11][12][13]

- Modified Mayo Wrist (MMW) questionnaire[11][12]

- Pain Scales (VAS/NPR)[11][12][13]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Typically some swelling is visible on the dorsal side of the wrist, along with synovitis.[15] The patient can experience a certain pain situated to the crucifixion fossa, which can be seen between the tendons of both the M. Extensor Digitorum and M. Extensor Carpi Radialis.[16] Furthermore, stiffness and tenderness may develop over the lunate bone.[15]

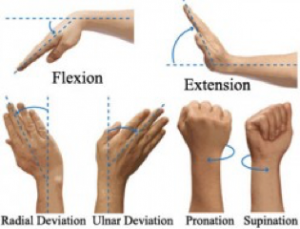

On physical inspection, the range of motion is quite sensitive, especially when extending the wrist. Movements such as flexion and extension are shrunken, sometimes combined with a progressively loss of grip strength.[16][15] However, the rotation of the forearm is still maintained.

Management[edit | edit source]

The goal of treating Kienböck disease is pain relief, wrist motion preservation, and preservation of grip strength.

Treatment of Kienböck disease depends on the stage of the disease and its causative factors. Stage I is always treated with splinting or cast immobilization. Stage II can also be treated with immobilization if necrosis is incomplete. Stages II with complete necrosis, III, and IV require "joint-leveling" surgery possibly coupled with vascular bone grafting or transfer of branches from adjacent arteries. Later stages with lunate collapse and secondary wrist degenerative arthrosis may also require proximal row carpectomy or intercarpal arthrodesis. Radial shortening osteotomy is the most common procedure performed to unload the lunate in cases with coexistent ulnar negative variance. Treatment may improve symptoms and functionality without affecting imaging findings in the advanced stages.[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is not a common treatment for this disease. A few studies investigated the efficacy of a physical therapeutic intervention following surgery. One study combined a bone marrow transfusion (medical), low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (PT) and an external fixation (surgery). For most of the patients in this study, wrist pain improved to a pain-free level, wrist flexion improved and average grip strength increased. This method can be used as a less invasive surgical alternative for Kienböck’s disease compared to the surgical procedures listed above.[17] Subsequent research is required to confirm the treatment effects found by these authors.

Another study compared different therapies after surgery. One group was treated according to a treatment protocol consisting of kinesiotherapy, electrotherapy, thermotherapy, massage therapy, therapeutic activities and domiciliary guiding. The other group was treated by non-specialized Departments in Hand Therapy and received only thermotherapy and exercises without a direct guidance from the therapist. After therapy, 90% of group one were satisfied with the results of the treatment and 66% of the second group. Other variables such as pain, muscular strength, prehension force, forearm articular range of motion for pronation and supination movements, wrist articular range of motion in abduction and adduction movements and manual function performance were also evaluated. Group one scored better than the second group but again, further research is needed to confirm these findings.[18]

A third study is a case study, reported on a 23 year old professional badminton player who had limited and painful wrist movements and was subsequently diagnosed with Kienböck’s disease. In this case study, the patient was treated surgically. For five weeks after the surgery, the wrist was splinted at all times and local anti-inflammatory and ice were used. Over the next eight weeks, stretching was increased gradually. Regular massage to the wrist extensor and flexor muscles was also done to decrease tone, which can affect joint function. At four months post-surgery, the wrist had painless 0-45° range of extension and 0-70° range of flexion. The patient started his regular training program with tape on his wrist for support. This is a case study thus the findings cannot be extrapolated to all patient populations.[19]

It is clear that there are too few studies about physical management of this condition.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Kienbock disease is invariably progressive, and joint destruction occurs within 3-5 years of onset.

Prognosis depends on:

- Functional Staging: The greater the extent of viable bone, the better the prognosis.[6]

- Negative ulnar variance: The greater the negative variance, the more severe the disease and the more likely it is to progress.

- Age at diagnosis: Patients diagnosed at an older age are more likely to have advanced stage disease and are more likely to progress.

It is significant to note that the severity of symptoms does not always correlate with morphologic stage.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Nasr LA, Koay J. Kienbock Disease.2019 Available:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/23892/ (accessed 1.10.21)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radiopedia Kienböck disease Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/kienbock-disease-2 (accessed 1.10.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 De Smet L et al., Treatment options in Kienböck’s disease, Acta Orthop. Belg., 2009, 75: 715-726.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Watson HK, Guidera PM. Aetiology of Kienbock's disease. J Hand Surg [Br]. Feb 1997;22(1):5-7.

- ↑ Cerezal L et al., Imaging Findings in Ulnar-sided Wrist impaction Syndromes, RadioGraphics, 2002, 22(1): 105-121

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 Arnaiz J et al., Imaging of Kienböck Disease, American Journal of Roentgenology, 2014, 203: 131-139.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Schuind F et al., Kienböck’s disease, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2008, 90-B: 133-139.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Allan CH et al., Kienböck’s Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment, Kienböck’s Disease, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2001, 9(2): 128-136.

- ↑ Patel N et al., Osteoarthritis of the Wrist, Osteoarthritis - Diagnosis, Treatment and Surgery, 2012, 171-202

- ↑ Watanabe K, Nakamura R, Imaeda T. Arthroscopic assessment of Kienbock's disease. Arthroscopy. Jun 1995;11(3):257-62.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Stahl et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2015) 10:133 DOI 10.1186/s13018-015-0276-7

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Ebrahimzadeh H. M, Moradi A, Vahedi E, Kachooei R A. Mid-term clinical outcome of radial shortening for kienbock disease. J Res Med Sci. 2015 February; 20(2): 146–149

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Lindsay Innes, BS, Robert J. Strauch. Systematic Review of the Treatment of Kienböck’s Disease in Its Early and Late Stages. J Hand Surg 2010; 35A:713

- ↑ Martin, G. R., & Squire, D. (2013). Long-term outcomes for Kienböck’s disease. Hand (New York, N.Y.), 8(1), 23–26. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-012-9470-9

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Lutsky K et al., Kienböck Disease, American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 2012, 37(A): 1942-1952.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Fontaine C et al., Kienböck's disease: la maladie de Kienböck, Chirurgie de la Main, 2015, 34(1): 4–17.

- ↑ Ogawa T et al., A new treatment strategy for Kienböck’s disease: combination of bone marrow transfusion, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy, and external fixation, J Orthop Sci., 2013, 18(2): 230-237.

- ↑ Lima SMPF et al., Rehabilitation of patients with Kienböck disease underwent proximal row carpectomy, Acta Ortop. Bras., 2000;8(2): 83-89

- ↑ Karahan AY et al., Kienbock’s Disease That Manifested in a Badminton Player: Case Report, International Journal of Sports Science 2013, 3(4): 132-134.