Idiopathic Toe Walking: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Lauren Heydenrych|User Name]] | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Idiopathic toe walking (ITW) is a diagnostic term used to describe a condition in otherwise healthy, ambulant children who present with a toe-toe gait. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, where no determinable pathology exists. | Idiopathic toe walking (ITW) is a diagnostic term used to describe a condition in otherwise healthy, ambulant children who present with a toe-toe gait. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, where no determinable pathology exists.[https://daniz53y71u1s.cloudfront.net/documents/idiopathic-toe-walking-pdf-new-9.pdf] | ||

Toe walking itself occurs in the absence of heel strike during initial contact together with the absence of full contact of the foot during stance phase in the [[Gait|gait cycle]]. Weight is kept primarily on the forefoot, often on the metatarsal heads.<ref name=":3">Van Kuijk AA, Kosters R, Vugts M, Geurts AC. Treatment for idiopathic toe walking: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2014 Nov 1;46(10):945-57.</ref> <ref name=":0">Dilger N. Idiopathic Toe Walking: A diagnosis of Exclusion or a Developmental Marker. Los Angeles, California. Footprints Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2005</ref> | Toe walking itself occurs in the absence of heel strike during initial contact together with the absence of full contact of the foot during stance phase in the [[Gait|gait cycle]]. Weight is kept primarily on the forefoot, often on the metatarsal heads.<ref name=":3">Van Kuijk AA, Kosters R, Vugts M, Geurts AC. Treatment for idiopathic toe walking: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2014 Nov 1;46(10):945-57.</ref> <ref name=":0">Dilger N. Idiopathic Toe Walking: A diagnosis of Exclusion or a Developmental Marker. Los Angeles, California. Footprints Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2005</ref> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 10: | ||

An operational definition given by Dilger <ref name=":0" /> is “an equinus gait, initially without fixed contractures, with passive dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) of the plantar flexor musculature to dorsiflex to at least neutral (0°) with the subtalar joint inverted and with the knee extended." | An operational definition given by Dilger <ref name=":0" /> is “an equinus gait, initially without fixed contractures, with passive dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) of the plantar flexor musculature to dorsiflex to at least neutral (0°) with the subtalar joint inverted and with the knee extended." | ||

ITW is also known as toe walking, habitual toe walking, and congenital short tendo calcaneus. <ref name=":1" /> | ITW is also known as toe walking, habitual toe walking, and congenital short tendo calcaneus. <ref name=":1">· Le Cras S, Bouck J, Brausch S, Taylor-Haas A. Evidence-based Clinical Care Guideline for Management of Idiopathic Toe Walking. Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Guideline 040, pages 1-17 (2011).</ref> | ||

ITW may initially present in pre-walking skill acquisition, the start of independent walking, or within 6 months of the initiation of independent walking. <ref name=":1" /> | ITW may initially present in pre-walking skill acquisition, the start of independent walking, or within 6 months of the initiation of independent walking. <ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 25: | Line 21: | ||

== Aetiology == | == Aetiology == | ||

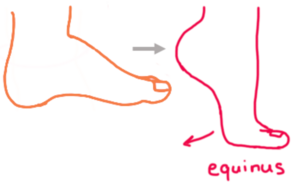

[[File:Equinus illustration.png|thumb|Equinus foot/ Forefoot weight bearing]] | [[File:Equinus illustration.png|thumb|Equinus foot/ Forefoot weight bearing]] | ||

Children diagnosed with ITW also often present with ankle equinus and/ or limited range in the ankle | Children diagnosed with ITW also often present with ankle equinus and/ or limited range in the ankle plantar flexors. Initially, this was thought to be a causational factor, but in more recent studies it is thought to be more a ''result'' of ITW. <ref name=":3" /> | ||

When it was initially described in the 1960's a genetically inherited trait was attributed to its development.<ref name=":0" /> | When it was initially described in the 1960's a genetically inherited trait was attributed to its development.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 27: | ||

Another, more recent school of thought is that ITW is a product of hyperreactivity of reflexes; an adaption to sensory feedback.<ref name=":2" /> It has been hypothesized that a delay in maturation of the corticospinal tract results in a lack of inhibition of the stretch reflexes and subsequent increased deep tendon reflexes. The literature review performed by Lorentzen et al.<ref name=":2" /> found that corticospinal pathways are active and important at the level of the presynapse of motor neurons of the ankle plantar flexors. | Another, more recent school of thought is that ITW is a product of hyperreactivity of reflexes; an adaption to sensory feedback.<ref name=":2" /> It has been hypothesized that a delay in maturation of the corticospinal tract results in a lack of inhibition of the stretch reflexes and subsequent increased deep tendon reflexes. The literature review performed by Lorentzen et al.<ref name=":2" /> found that corticospinal pathways are active and important at the level of the presynapse of motor neurons of the ankle plantar flexors. | ||

In regard to the feedforward mechanisms, dysregulation in sensory integration has been hypothesized. Sensory integration is "the registration and modulation of sensory input for the execution of motor output". <ref name=":0" /><sup>(p.4)</sup> Examples of disrupted regulation can be viewed with hypertonia, leading to decreased proprioceptive and vestibular input, and thus altered biomechanics, seeking further input through the metatarsal joints. On the opposite end of the spectrum, tactile defensiveness resulting from the input which is perceived as too much or noxious could also result in toe walking gait.<ref name=":0" /> | In regard to the feedforward mechanisms, dysregulation in sensory integration has been hypothesized. Sensory integration is "the registration and modulation of sensory input for the execution of motor output". <ref name=":0" /><sup>(p.4)</sup> Examples of disrupted regulation can be viewed with hypertonia, leading to decreased proprioceptive and vestibular input, and thus altered biomechanics, seeking further input through the metatarsal joints. On the opposite end of the spectrum, tactile defensiveness resulting from the input which is perceived as too much or noxious could also result in toe walking gait.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== Associated pathology == | |||

While there is no known cause for ITW, it has been associated with other conditions including developmental delay, cognitive delay, and children diagnosed as having [[Autism Spectrum Disorder|autism spectrum disorder]] (ASD).<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Pathophysiology == | == Pathophysiology == | ||

| Line 38: | Line 37: | ||

Muscle biopsies done also indicate a higher percentage of [[Muscle Fibre Types|type I muscle fibres]] in the gastrocnemius muscle than what would be expected.<ref name=":0" /> <ref name=":2" /> | Muscle biopsies done also indicate a higher percentage of [[Muscle Fibre Types|type I muscle fibres]] in the gastrocnemius muscle than what would be expected.<ref name=":0" /> <ref name=":2" /> | ||

== | == Diagnosis == | ||

Diagnosis is one of exclusion. Hence the differential diagnosis is used. The following is a list of diagnoses to rule out:<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4">Caserta AJ, Pacey V, Fahey MC, Gray K, Engelbert RH, Williams CM. Interventions for idiopathic toe walking. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(10).</ref> | Diagnosis is one of exclusion. Hence the differential diagnosis is used. The following is a list of diagnoses to rule out:<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4">Caserta AJ, Pacey V, Fahey MC, Gray K, Engelbert RH, Williams CM. Interventions for idiopathic toe walking. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(10).</ref> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 46: | ||

* Tethered cord syndrome | * Tethered cord syndrome | ||

* Spinal dysraphism | * Spinal dysraphism | ||

* Spinal cord | * Spinal cord tumor | ||

[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20692159/ The Toe-walking tool] is a series of questions which is claimed to be a valid and reliable tool for distinguishing ITW from other conditions | |||

== Diagnostic procedures == | == Diagnostic procedures == | ||

Despite | Despite no known cause, studies have shown persistent gait kinematic and EMG abnormalities, even when attempting heel-toe walk. <ref name=":1" /> In studies done with EMG, it was ascertained that the gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior (TA) were out of phase, or imbalanced. Early and predominant firing was noted in the gastrocnemius muscles during the swing and stance phase. In addition, low amplitude of TA was noted during both stance and swing. These results showed some evidence in the ability to diagnose ITW through EMG<ref name=":1" /> <ref name=":3" />Caution must be used when considering this as a form of diagnosis. In the study performed by Dilger<ref name=":0" />showed similar firing patterns to that of children diagnosed with mild cerebral palsy. | ||

== Management == | == Management == | ||

| Line 69: | Line 71: | ||

Surgical interventions described in the literature include: | Surgical interventions described in the literature include: | ||

* [https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagrams-of-other-techniques-of-aponeurotic-lengthening-showing-a-Vulpius-b-Baker-and_fig3_12462539 Vulpius procedure] ( | * [https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagrams-of-other-techniques-of-aponeurotic-lengthening-showing-a-Vulpius-b-Baker-and_fig3_12462539 Vulpius procedure] (gastrocnemius recession surgery)<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

* Tendon | * Tendon archilles lengthening. In a systematic review of this procedure, an increased popliteal angle was noted, however, there was no real change to the hip and knee alignment of individuals after 1 year follow-up. The hips still displaying external rotation and knee tibial torsion. <ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

* Open | * Open achilles tendon lengthening via a Z-lengthening or slide technique <ref name=":4" /> | ||

* Baker’s gastrocnemius-soleus lengthening. <ref name=":4" /> | * Baker’s gastrocnemius-soleus lengthening. <ref name=":4" /> | ||

Side effects to surgical management noted in Caserta et al. <ref name=":4" /> as well as Van Kuijk et al. <ref name=":3" /> included excessive ankle dorsiflexion after tendon | Side effects to surgical management noted in Caserta et al. <ref name=":4" /> as well as Van Kuijk et al. <ref name=":3" /> included excessive ankle dorsiflexion after tendon archilles lengthening. | ||

== Physiotherapy management == | == Physiotherapy management == | ||

| Line 81: | Line 83: | ||

=== Assessment === | === Assessment === | ||

Components of a physical therapy examination history | Components of a physical therapy examination history are detailed in the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Centre’s Guideline in the Management of Idiopathic Toe Walking.<ref name=":1" /> It includes the following: | ||

* Subjective examination | * Subjective examination | ||

| Line 113: | Line 115: | ||

* Ankle DF in active range of movement (AROM) with knee extended | * Ankle DF in active range of movement (AROM) with knee extended | ||

* Muscle length tests including: | * Muscle length tests including: | ||

* Thomas test (hip flexors) | ** Thomas test (hip flexors) | ||

* Hamstring length test | ** Hamstring length test | ||

* Lower extremity (LE) alignment including: | ** Lower extremity (LE) alignment including: | ||

* Thigh foot angle (TFA) | ** Thigh foot angle (TFA) | ||

* Hindfoot/forefoot alignment in STN (non-weight bearing) | ** Hindfoot/forefoot alignment in STN (non-weight bearing) | ||

* Standing posture | * Standing posture | ||

* LE strength (MMT (manual muscle testing) and/or functional assessment) of | * LE strength (MMT (manual muscle testing) and/or functional assessment) of | ||

* Anterior tibialis | ** Anterior tibialis | ||

* Gastrocnemius | ** Gastrocnemius | ||

* Trunk and core strength | * Trunk and core strength | ||

Revision as of 19:59, 26 April 2022

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Lauren Heydenrych, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Tarina van der Stockt and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Idiopathic toe walking (ITW) is a diagnostic term used to describe a condition in otherwise healthy, ambulant children who present with a toe-toe gait. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, where no determinable pathology exists.[1]

Toe walking itself occurs in the absence of heel strike during initial contact together with the absence of full contact of the foot during stance phase in the gait cycle. Weight is kept primarily on the forefoot, often on the metatarsal heads.[1] [2]

An operational definition given by Dilger [2] is “an equinus gait, initially without fixed contractures, with passive dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) of the plantar flexor musculature to dorsiflex to at least neutral (0°) with the subtalar joint inverted and with the knee extended."

ITW is also known as toe walking, habitual toe walking, and congenital short tendo calcaneus. [3]

ITW may initially present in pre-walking skill acquisition, the start of independent walking, or within 6 months of the initiation of independent walking. [3]

While some patients who present with ITW do so 100% during gait, some are able to spontaneously move to a heel-toe gait pattern. [3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Reports of the incidence of ITW vary considerably. From 7%-24% [5]to between 2% - 5%[3][6]This is seen in part because much of the literature views toe-walking as part of normal gait development in children under the age of 2 years[1]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Children diagnosed with ITW also often present with ankle equinus and/ or limited range in the ankle plantar flexors. Initially, this was thought to be a causational factor, but in more recent studies it is thought to be more a result of ITW. [1]

When it was initially described in the 1960's a genetically inherited trait was attributed to its development.[2]

Another, more recent school of thought is that ITW is a product of hyperreactivity of reflexes; an adaption to sensory feedback.[6] It has been hypothesized that a delay in maturation of the corticospinal tract results in a lack of inhibition of the stretch reflexes and subsequent increased deep tendon reflexes. The literature review performed by Lorentzen et al.[6] found that corticospinal pathways are active and important at the level of the presynapse of motor neurons of the ankle plantar flexors.

In regard to the feedforward mechanisms, dysregulation in sensory integration has been hypothesized. Sensory integration is "the registration and modulation of sensory input for the execution of motor output". [2](p.4) Examples of disrupted regulation can be viewed with hypertonia, leading to decreased proprioceptive and vestibular input, and thus altered biomechanics, seeking further input through the metatarsal joints. On the opposite end of the spectrum, tactile defensiveness resulting from the input which is perceived as too much or noxious could also result in toe walking gait.[2]

Associated pathology[edit | edit source]

While there is no known cause for ITW, it has been associated with other conditions including developmental delay, cognitive delay, and children diagnosed as having autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[1][2]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

While the etiology of ITW remains unclear, there is consensus that as the child progresses in age, certain biomechanical changes occur. This includes shortened tendon achilles, as well as contractures of the foot and ankle joints. This is more prominent in older children presenting with ITW [3][1][2]

Muscle biopsies done also indicate a higher percentage of type I muscle fibres in the gastrocnemius muscle than what would be expected.[2] [6]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is one of exclusion. Hence the differential diagnosis is used. The following is a list of diagnoses to rule out:[1][7]

- Neuromotor disease

- Neuromuscular disease

- Cerebral palsy

- Spina Bifida

- Tethered cord syndrome

- Spinal dysraphism

- Spinal cord tumor

The Toe-walking tool is a series of questions which is claimed to be a valid and reliable tool for distinguishing ITW from other conditions

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

Despite no known cause, studies have shown persistent gait kinematic and EMG abnormalities, even when attempting heel-toe walk. [3] In studies done with EMG, it was ascertained that the gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior (TA) were out of phase, or imbalanced. Early and predominant firing was noted in the gastrocnemius muscles during the swing and stance phase. In addition, low amplitude of TA was noted during both stance and swing. These results showed some evidence in the ability to diagnose ITW through EMG[3] [1]Caution must be used when considering this as a form of diagnosis. In the study performed by Dilger[2]showed similar firing patterns to that of children diagnosed with mild cerebral palsy.

Management[edit | edit source]

Initial management is conservative, with some of these treatment regimes including Botulism Toxin A (BTX). Surgical intervention is usually undertaken when conservative measures have been exhausted.[3] [1][7]

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment can include the following[7]:

- Serial casting

- Orthotics

- Footwear

- Auditory feedback

- Physiotherapy

- BTX

- In a study performed in 2004 by Brunt et al.[8], cited in Van Kuijk [1] , BTX was used to treat triceps surae activity. With EMG as assessment, the activity of the muscle group was brought more closely to resemble normal activity immediately after treatment and at 1-year follow-up. Reports from a Cochrane review[7] found that BTX had some success when done together with other conservative interventions including casting and footwear. Intervention in these studies was considered successful when toe walking was performed less than 50% of the time walking. [7]

Surgical management[edit | edit source]

Surgical interventions described in the literature include:

- Vulpius procedure (gastrocnemius recession surgery)[1][7]

- Tendon archilles lengthening. In a systematic review of this procedure, an increased popliteal angle was noted, however, there was no real change to the hip and knee alignment of individuals after 1 year follow-up. The hips still displaying external rotation and knee tibial torsion. [1][7]

- Open achilles tendon lengthening via a Z-lengthening or slide technique [7]

- Baker’s gastrocnemius-soleus lengthening. [7]

Side effects to surgical management noted in Caserta et al. [7] as well as Van Kuijk et al. [1] included excessive ankle dorsiflexion after tendon archilles lengthening.

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

As with all therapeutic interventions, initial consult begins with a thorough assessment, followed by treatment and reassessment.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Components of a physical therapy examination history are detailed in the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Centre’s Guideline in the Management of Idiopathic Toe Walking.[3] It includes the following:

- Subjective examination

- Objective examination, including certain screenings

- Physical examination

- Gait examination

- Gross motor skills

Subjective examination[edit | edit source]

- Birth history

- Medical history

- Developmental history: This would include 3 components

- Gross motor skills development

- Balance concerns

- Onset of toe walking

- Family history of toe walking, and/or any conditions associated with toe walking

- Current and past therapeutic interventions. For example, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy etc.

Objective screening[edit | edit source]

- Pain assessment using an appropriate pain scale

- Speech and language screening (Communication subsection of Ages and Stages Questionnaire; for ages 4 months to 60 months)

- Short Sensory Profile (for ages 3 years to 10 years 11 months). This to be done by the first treatment visit.

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

- Muscle tone of ankle plantar flexors and knee flexors using the Modified Ashworth

- Clonus

- Ankle dorsiflexion (DF) in passive range of movement (PROM) in subtalar neutral (STN), with knee flexed and extended.

- Ankle DF in active range of movement (AROM) with knee extended

- Muscle length tests including:

- Thomas test (hip flexors)

- Hamstring length test

- Lower extremity (LE) alignment including:

- Thigh foot angle (TFA)

- Hindfoot/forefoot alignment in STN (non-weight bearing)

- Standing posture

- LE strength (MMT (manual muscle testing) and/or functional assessment) of

- Anterior tibialis

- Gastrocnemius

- Trunk and core strength

Gait examination[edit | edit source]

- Observational Gait Scale (OGS)

- Parent report of percentage of time toe walking

Gross motor skills assessment[edit | edit source]

- Squatting to/from standing position, position of foot squatting

- Transition from floor to stand

- Stairs

- Balance including components…

- Static and dynamic balance

- Single limb stance

- Balance beam

- Jumping/ Hopping

- Coordination

- Determine need for standardized testing

Further details in progressive reassessment during follow-up consultation can be found in the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Centre’s Guideline.

Physiotherapy intervention[edit | edit source]

A physiotherapist's role in the management of ITW is multidimensional and includes the following[2].

- Hands-on therapy

- Active and passive range exercises, emphasis on the ankles.

- Strength training

- Gait training

- Home exercise program prescription

- In addition to the above, the physiotherapist will also be involved in footwear, casting and orthotic intervention. Whether this is again a hands-on aspect or on a consultative level.

Additional Viewing[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Liesa Ritchie-Persaud's Top Tips and Tools for Treating Toe-Walking: https://www.wiredondevelopment.com/single-post/2017/02/17/liesa-persauds-top-tips-and-tools-for-treating-toe-walking

Dr Cylie Williams: A Podiatrist's Perspective on paediatric feet and gait concerns:https://www.wiredondevelopment.com/single-post/2018/04/22/dr-cylie-williams-a-podiatrists-perspective-on-paediatric-feet-and-gait-concerns

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Van Kuijk AA, Kosters R, Vugts M, Geurts AC. Treatment for idiopathic toe walking: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2014 Nov 1;46(10):945-57.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Dilger N. Idiopathic Toe Walking: A diagnosis of Exclusion or a Developmental Marker. Los Angeles, California. Footprints Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2005

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 · Le Cras S, Bouck J, Brausch S, Taylor-Haas A. Evidence-based Clinical Care Guideline for Management of Idiopathic Toe Walking. Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Guideline 040, pages 1-17 (2011).

- ↑ Paediatric Foot & Ankle. Toe Walking What Every Parent Should Know. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8__feVE3lI [last accessed 25/04/2022]

- ↑ Sobel E, Caselli MA, Velez Z. Effect of persistent toe walking on ankle equinus. Analysis of 60 idiopathic toe walkers. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 1997 Jan;87(1):17-22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Lorentzen J, Willerslev‐Olsen M, Hüche Larsen H, Svane C, Forman C, Frisk R, Farmer SF, Kersting U, Nielsen JB. Feedforward neural control of toe walking in humans. The Journal of physiology. 2018 Jun;596(11):2159-72.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Caserta AJ, Pacey V, Fahey MC, Gray K, Engelbert RH, Williams CM. Interventions for idiopathic toe walking. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(10).

- ↑ Brunt D, Woo R, Kim HD, Ko MS, Senesac C, Li S. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on gait of children who are idiopathic toe-walkers. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2004 Jan 1;13(3):149-55.

- ↑ AMy Sturkey. #5 A Comparison of Walking in Typical vs Toe Walkers: Pediatric Physical Therapy for Toe Walkers. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BIUrcHDLD1M [last accessed 26/04/2022

- ↑ Liesa Persaud. Toe Walking Video: Base of Support - MedBridge. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYYFSSIB5h8 [last accessed 26/04/2022]