Hallux Valgus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (177 intermediate revisions by 19 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Bradley Svoboda|Bradley Svoboda]] | |||

{ | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | |||

== Introduction == | |||

Hallux Valgus is considered one of the most common foot deformities,<ref>Mortka K, Lisiński P. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4668189/pdf/jpts-27-3303.pdf Hallux valgus-a case for a physiotherapist or only for a surgeon? Literature review.] J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Oct;27(10):3303-7</ref> and is described as “lateral deviation of the hallux and its consequent distancing from the median axis of the body”.<ref name=":3">Cavalheiro CS, Arcuri MH, Guil VR, Gali JC. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7006535/pdf/1809-4406-aob-28-01-12.pdf HALLUX VALGUS ANATOMICAL ALTERATIONS AND ITS CORRELATION WITH THE RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS.] Acta Ortop Bras. 2020 Jan-Feb;28(1):12-15.</ref> Treatment for hallux valgus ranges from conservative to surgical management.<ref>Wojcik B, Fabiś M, Zadroźna K, Małek A, Iwaniszyn-Zapołoch K, Remjasz K,Aleksandrowicz J, Siedlecki W. Hallux valgus treatment and new methods. Journal of Education, Health and Sport [online]. 2022;12( 9): 614–620. [last access 18.02.2023]</ref> There are about 131 different surgical techniques. However, no method is available thus far that sufficiently corrects all hallux valgus deformities.<ref name=":1">Joseph TN, Mroczek KJ. Decision making in the treatment of hallux valgus. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(1):19-23. </ref> This article will discuss pre and post-operative hallux valgus management principles. | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

[[File:Foot inferior.png|thumb|Plantar surface of the foot]] | |||

| | === Bones === | ||

The [[Metatarsals|first metatarsal]], proximal phalanx, and distal phalanx form the hallux or first toe. In addition, two [[Sesamoid|sesamoid bones]] (medial and lateral) contribute to the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Their dorsal surface articulates with the plantar aspect of the first metatarsal head and is contained within the [[Flexor Hallucis Brevis|flexor hallucis brevis]] muscle tendon. The first metatarsal head is responsible for good static and dynamic weight bearing. The sesamoid bones protect the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis and help generate more force by extending its levers. | |||

== | === Joints === | ||

The hallux metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) is a synovial joint. Three joints are part of this system: | |||

* [[Foot Anatomy|Tarsometatarsal joint]] -located between the medial cuneiform bone and the first metatarsal. | |||

* [[Foot Anatomy|Metatarsophalangeal joint]] - connects the first metatarsal and the first proximal phalanx. | |||

* [[Foot Anatomy|Interphalangeal joint]] - situated between the two phalanges of the first toe. | |||

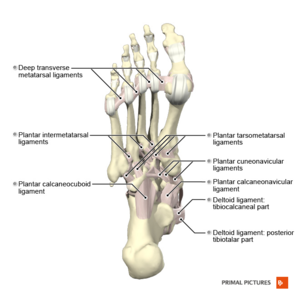

[[File:Ligaments of the foot plantar aspect Primal.png|thumb|Ligaments of the foot plantar aspect]] | |||

== | === Ligaments'''<ref>Hallinan JTPD, Statum SM, Huang BK, Bezerra HG, Garcia DAL, Bydder GM, Chung CB. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7337226/pdf/rg.2020190145.pdf High-Resolution MRI of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint: Gross Anatomy and Injury Characterization.] Radiographics. 2020 Jul-Aug;40(4):1107-1124.</ref>''' === | ||

The | * The intersesamoid ligament (ISL) links two sesamoids and indirectly connects the [[Flexor Hallucis Brevis|flexor hallucis brevis]] (FHB), [[Abductor Hallucis|abductor hallucis]], and [[Adductor Hallucis|adductor hallucis]] tendons. | ||

* Sesamoid phalangeal ligaments (SPLs) are the thickest first MTPJ ligaments. They protect the sesamoids from subluxation when high tensile forces act upon them while walking or running. | |||

* Metatarsosesamoid ligaments (MTSLs), or suspensory ligaments, are part of the plantar plate complex. They assist with stabilising the sesamoids. | |||

* Medial and lateral metatarsophalangeal ligaments (collateral ligaments) attach at the peripheral sesamoids. They are not part of the plantar plate complex but play an essential role as static stabilisers when applying valgus or varus forces. | |||

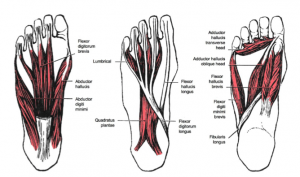

[[File:Intrinsic foot muscles.png|thumb|Intrinsic foot muscles]] | |||

== | === Muscles === | ||

The following muscles act on the first MTP joint: [[Tibialis Anterior|tibialis anterior]], [[Extensor Hallucis Longus|extensor hallucis longus]], [[Peroneus (Fibularis) Longus Muscle|peroneus longus]], flexor hallucis longus, extensor hallucis brevis, [[Abductor Hallucis|abductor hallucis]], [[Flexor Hallucis Brevis|flexor hallucis brevis]], [[Adductor Hallucis|adductor hallucis]], [[Dorsal Interossei of the Foot|dorsal interossei]], and [[Aponeurosis|aponeurosis plantaris]]. | |||

The | The muscle responsible for the motion control at the first MPJ is [[Extensor Hallucis Brevis|extensor hallucis brevis]], abductor hallucis, flexor hallucis brevis, and adductor hallucis. The abductor hallucis contributes to the abduction and flexion of the first MPJ. In addition to the foot's intrinsic muscles, the flexor hallucis longus contributes to the flexion of the distal phalanx of the hallux and the extensor hallucis longus to its extension.<ref>J.S. Kawalec JS. 12 - Mechanical testing of foot and ankle implants. Editor(s): Friis E. Mechanical Testing of Orthopaedic Implants. Woodhead Publishing 2017: pages 231-253</ref> | ||

== | === Motion === | ||

The primary motion of the metatarsophalangeal joint is flexion and extension with minimal abduction and adduction. The collateral ligaments limit mediolateral movement in the joint.<ref>Mojica MN, John S. Early JS.19 - Foot Biomechanics. Editor(s): Webster JB, Murphy DP. Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices (Fifth Edition),Elsevier, 2019: 216-228.e1.</ref> | |||

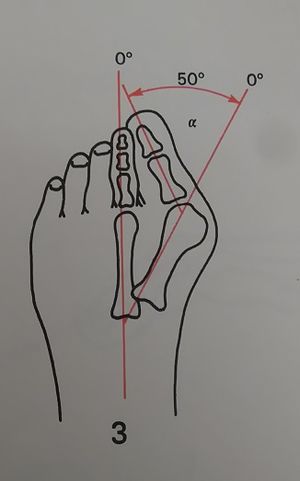

[[File:Hallux valgus angle 2.jpg|thumb|Hallux Valgus Angle]] | |||

==== Hallux Valgus Angle ==== | |||

* The angle created between the lines that longitudinally bisect the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal. | |||

* Less than 15° is considered normal. Angles of 20° and greater are considered abnormal. An angle of 45-50° is considered severe. | |||

== Epidemiology and Aetiology == | |||

Hallux Valgus deformity is a complex condition. It has a familial tendency that depends on autosomal dominant inheritance's transmission with incomplete penetrance.<ref name=":3" /> Other aetiologic factors include the following: | |||

* | * Gender (more common in women than men (ratio of 15:1)<ref>Kakwani M, Kakwani R. Current concepts review of hallux valgus. Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery. 2021;8(3):222-30.</ref> | ||

* | * Footwear (tight, pointed shoes) | ||

* | ** Menz et al. found that wearing constrictive footwear "between the ages of 20 and 39 years may be a critical period for the development of hallux valgus in later life"<ref>Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M, Thomas MJ, Rathod T, Peat GM, Croft PR. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5106851/ Epidemiology of shoe wearing patterns over time in older women: associations with foot pain and hallux valgus]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Dec;71(12):1682-7. </ref> | ||

* Congenital deformity | |||

* Anatomical and biomechanical factors, such as | |||

** long first metatarsal | |||

** rounded joint | |||

** metatarsus primus varus | |||

* Chronic [[Achilles Tendon|Achilles tendon]] tightness | |||

* Severe flatfoot | |||

* Hypermobility of the first metatarsocuneiform joint | |||

* Systemic disease | |||

* Abnormal muscle insertions | |||

* Hip and knee [[osteoarthritis]]<ref>Hannan MT, Menz HB, Jordan JM, Cupples LA, Cheng C-H, Hsu Y-H. Hallux Valgus and Lesser Toe Deformities are Highly Heritable in Adult Men and Women: the Framingham Foot Study. Arthritis care & research. 2013;65(9):1515-1521. </ref><ref>Golightly YM, Hannan MT, Dufour AB, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Factors Associated with Hallux Valgus in a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study of Adults with and without Osteoarthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(6):791-798. </ref><ref>Barnish MS, Barnish J. High-heeled shoes and musculoskeletal injuries: a narrative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010053</ref><ref>Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M, et al. Epidemiology of Shoe Wearing Patterns Over Time in Older Women: Associations With Foot Pain and Hallux Valgus. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2016;71(12):1682-1687. </ref> | |||

* High [[Body Mass Index|Body Mass Index (BMI)]] | |||

[[File:Hallux valgus anatomy.jpg|thumb|Anatomy of the Hallux Valgus]] | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

== | === Biomechanical Factors<ref name=":3" /> === | ||

Hallux valgus pathology is consistent with bone deviation and destabilisation of the muscle group around the joint. The following process may occur in stages or parallel: | |||

* Initial injury relates to the failure of the medial sesamoid and the medial collateral ligaments | |||

* Medial deviation of the first metatarsal head | |||

* Valgus deformity of the proximal phalanx while its base is fixed to the sesamoid, transverse ligament and adductor hallucis tendon | |||

* The lateral arching of the extensor and flexor hallucis longus tendons increases valgus deformity | |||

* The adductor hallucis tendon pulls the phalanx in pronation, causing dislocation of the phalanx base | |||

* First metatarsophalangeal joint rotates medially with pronation and becomes unstable | |||

<blockquote>The end result is lateral deviation and lateral rotation of the hallux with medial deviation and lateral rotation of the first metatarsal. </blockquote>{{#ev:youtube|L_orU3MgOVw|400}} <ref>Biomechanix Foot and Knee Clinic. Hallux Valgus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_orU3MgOVw [last accessed 08/01/17]</ref> | |||

== | === Signs and Symptoms === | ||

* Joint inflammation | |||

* Initial pain and tenderness of the bunion with footwear | |||

* Alteration in the skin over the bunion: it becomes hard, warm and red | |||

* Bony enlargement of the first metatarsal head<ref>Menz HB, Munteanu SE. Radiographic validation of the Manchester scale for the classification of hallux valgus deformity. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 Aug;44(8):1061-6.</ref> | |||

* Progression in pain as the bunion size increases | |||

* [[Gait Deviations|Gait deviations]] in the midstance (middle stage) and the propulsion phase (late stance). | |||

** As the bodyweight moves forward on a foot on the ground, the patient will tend to keep their weight on the lateral border of the foot | |||

** Lateral and posterior weight shift | |||

** Late heel rise due to body weight shifted on the lateral border of the foot | |||

** Reduced time in single-limb support <ref name=":4">Dimonte P, Light H. Pathomechanics, gait deviations, and treatment of the rheumatoid foot: a clinical report. Phys Ther. 1982 Aug;62(8):1148-56.</ref> | |||

* Foot pronation deformity | |||

* Weakness of hallux abductor muscles<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* Shortening of flexor hallucis brevis muscle | |||

== Management | == Pre-operative Management == | ||

* Patient education regarding recovery time | |||

<blockquote>“I think it would be useful if you know of a patient that is thinking about having the surgery, discuss it with them, give them the stuff to read and make sure that they understand what they are letting themselves in for.” ''Helene Simpson'' <ref name=":6">Simpson H. Hallux Valgus. Plus Course 2020</ref><br></blockquote> | |||

== Operative Treatment == | |||

Despite many surgical procedures for treating hallux valgus, no single method can correct all deformities.<ref name=":1" /> The surgeons decide about the type of procedure based on the results of their assessment which includes: | |||

* Close observation for an increased hallux valgus angle | |||

* Increased intermetatarsal (IM) angle | |||

* Pronation of the first toe | |||

* Increased distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA) | |||

* Enlarged medial eminence | |||

* Subluxation of the sesamoids | |||

'''Goals:''' | |||

# To maintain a flexible first MTP joint | |||

# To preserve the normal weight-bearing pattern of the forefoot | |||

'''Outcomes:''' | |||

< | * According to a study by Hernandez-Castillejo et al.,<ref>Hernández-Castillejo LE, Martínez Vizcaíno V, Garrido-Miguel M, Cavero-Redondo I, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Álvarez-Bueno C. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8023907/pdf/IORT_91_1764193.pdf Effectiveness of hallux valgus surgery on patient quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis]. Acta Orthop. 2020 Aug;91(4):450-456.</ref> hallux valgus surgery decreased patient perception of pain and increased Quality of Life in the physical and social domains | ||

* Goh et al.<ref>Goh GS, Tay AY, Thever Y, Koo K. Effect of age on clinical and radiological outcomes of hallux valgus surgery. Foot & Ankle International. 2021 Jun;42(6):798-804.</ref> concluded that age did not influence the perioperative, functional, or subjective outcomes following hallux valgus surgery, but older patients may be at higher risk of recurrence | |||

== Post-operative Management == | |||

'''General Guidelines:''' | |||

* At least six weeks of non-weight bearing | |||

* Immobilisation in a modified shoe | |||

* [[Oedema Assessment|Oedema]] management | |||

=== Physiotherapy === | |||

<blockquote>Look at the patient as a WHOLE: "fix the gait, check on the foot core, plantar push-off, shoe wear, make sure you address the pain, look at the whole kinetic chain and make sure you also match it to the shoes at the bottom." Helene Simpson <ref name=":6" /></blockquote> | |||

< | ==== Fixing Gait ==== | ||

After hallux valgus correction, patients may adopt the habit of walking on the side of their foot to avoid loading the recently operated big toe. This needs to be addressed to ensure good balance and stability and to prevent other injuries in the long term.<ref>Schuh R, Hofstaetter SG, Adams SB Jr, Pichler F, Kristen KH, Trnka HJ. [https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/89/9/934/2737642?login=false Rehabilitation after hallux valgus surgery: importance of physical therapy to restore weight bearing of the first ray during the stance phase.] Phys Ther. 2009 Sep;89(9):934-45.</ref> | |||

'''Goal:''' | |||

# To restore gait as closely as possible back to normal | |||

'''Strategies:''' | |||

* Look, film, address, correct. Repeat as necessary to ensure the patient's confidence in their gait | |||

* Facilitate loading the first metatarsal | |||

** Walk with a patient, one foot directly in front of the other | |||

** Forefoot mobilisation strategies, including plantar fascia lengthening, Achilles tendon lengthening | |||

==== Check the Foot Core ==== | |||

Targeted muscles for strengthening are:<ref>Glasoe WM. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/epdf/10.2519/jospt.2016.6704 Treatment of progressive first metatarsophalangeal hallux valgus deformity: a biomechanically based muscle-strengthening approach.] Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jul;46(7):596-605.</ref> | |||

* the intrinsics: abductor hallucis, adductor hallucis, and the flexor hallucis brevis | |||

* the extrinsics: tibialis posterior and fibularis longus | |||

'''Goal:''' | |||

# To strengthen the foot core | |||

[[File:Metatarsal doming.gif|thumb|Doming exercise]] | |||

'''Strategies:''' | |||

* Ask the patient to create a dome with their foot from a seated position by pressing the toes down and shortening the foot with isometric holds. | |||

* Ask the patient to press the first toe down and lift the other four toes, then switch around, push the four toes down and lift the big toe. | |||

* Add some resistance using an exercise band (put the band underneath and press down on it while pulling the band up with both hands). This exercise is called 'foot core plus'. | |||

* Ask the patient to do the same exercise while maintaining the foot dome. A further step would be to get the toes down, the first ray down, and then they can start lifting the heel all the time, maintaining a good foot posture. | |||

* Progress into standing, standing on one foot, walking, stepping up, stepping down. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|v=pmqBTq3HIJw|300}}<ref>Align Therapy. Strengthening the Foot Core! Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmqBTq3HIJw [last accessed 24/02/2023]</ref> | |||

== | ==== Planter Push-Off ==== | ||

'''Goal:''' | |||

# To improve the functional push-off | |||

'''Strategies:''' | |||

* Exercises | |||

** Standing over the edge of a box or a step with an exercise band - ask the patient to push through the band. | |||

** Walking with an exercise band underneath the toes and pulling it up - the patient pushes their toes down into the band as they walk, pressing down to push their foot off. | |||

** Soft tissue work is also essential, such as releasing the toe extensors. These muscles get stiff and lose the ability to slide smoothly through the extensor retinaculum in line with the syndesmosis. | |||

** Heel raises to strengthen the plantar flexors, and if they are tight, it is helpful to lengthen, release and stretch them by asking the patient to stand over the edge of a step and to drop their heels down. You can put cotton wool between the toes to stretch them. | |||

< | * Second toe mobility and flexibility | ||

{{#ev:youtube|v=h2kaEOd3GcI|300}}<ref>Northwest Foot & Ankle. Toe Extensor Stretch with Dr Ray McClanahan. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2kaEOd3GcI [last accessed 24/02/2023]</ref> | |||

==== Address the Pain ==== | |||

'''Goal:''' | |||

# To reduce pain and restore normal toe and foot joint range of motion and muscle length | |||

'''Strategies:''' | |||

* [[Desensitization|Desensitising]] techniques | |||

* [[Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)|Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation]] (TENS) | |||

* Medication review with the surgeon and the patient | |||

* Therapists need a good understanding of surgical techniques to avoid using techniques that could disturb bone healing, such as mobilising a scarf osteotomy | |||

* Sesamoid mobilisation: grade III joint mobilisations on the medial and lateral sesamoid of the affected first MPJ. | |||

** One thumb is placed on the proximal aspect of the sesamoid and is used to apply a force from proximal to distal that causes the sesamoid to reach the end range of motion (distal glides). These are performed with large-amplitude rhythmic oscillations. No greater than 20° of movement of the MPJ should be allowed during the technique.<ref>Shamus J, Shamus E, Gugel RN, Brucker BS, Skaruppa C. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/epdf/10.2519/jospt.2004.34.7.368 The effect of sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training on reducing pain and restoring function in individuals with hallux limitus: a clinical trial]. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Jul;34(7):368-76.</ref> '''NOTE''': '''''Always check operative protocol before choosing intervention. This technique is not suitable if a surgical procedure with fusion has been done.''''' | |||

==== Match the Shoe ==== | |||

'''Goal:''' | |||

# To provide needed support for sensitive and swollen foot | |||

'''Strategies:''' | |||

* Ask the patient what shoes they see themselves wearing | |||

* Assess the shoe the patient is currently wearing | |||

* The worn shoe may no longer be suitable - its shape may have changed to accommodate the pre-operative foot posture | |||

* A wider toe box and sound, solid heel structure can be useful | |||

* Do not wear flat leather sole shoes | |||

* Wearing silk socks or silky stockings can prevent friction and protect the scar | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Foot]] | |||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:Foot - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:10, 11 August 2023

Original Editors - Bradley Svoboda

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Van Horebeek Erika, Mariam Hashem, Ewa Jaraczewska, Lucinda hampton, Rachael Lowe, Jess Bell, Bradley Svoboda, Andeela Hafeez, Jolien Rottie, Admin, Kim Jackson, Morgane Michiels, Kristin Zumo, Khloud Shreif, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, Tinne Tielemans and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Hallux Valgus is considered one of the most common foot deformities,[1] and is described as “lateral deviation of the hallux and its consequent distancing from the median axis of the body”.[2] Treatment for hallux valgus ranges from conservative to surgical management.[3] There are about 131 different surgical techniques. However, no method is available thus far that sufficiently corrects all hallux valgus deformities.[4] This article will discuss pre and post-operative hallux valgus management principles.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

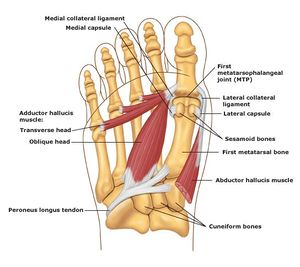

Bones[edit | edit source]

The first metatarsal, proximal phalanx, and distal phalanx form the hallux or first toe. In addition, two sesamoid bones (medial and lateral) contribute to the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Their dorsal surface articulates with the plantar aspect of the first metatarsal head and is contained within the flexor hallucis brevis muscle tendon. The first metatarsal head is responsible for good static and dynamic weight bearing. The sesamoid bones protect the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis and help generate more force by extending its levers.

Joints[edit | edit source]

The hallux metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) is a synovial joint. Three joints are part of this system:

- Tarsometatarsal joint -located between the medial cuneiform bone and the first metatarsal.

- Metatarsophalangeal joint - connects the first metatarsal and the first proximal phalanx.

- Interphalangeal joint - situated between the two phalanges of the first toe.

Ligaments[5][edit | edit source]

- The intersesamoid ligament (ISL) links two sesamoids and indirectly connects the flexor hallucis brevis (FHB), abductor hallucis, and adductor hallucis tendons.

- Sesamoid phalangeal ligaments (SPLs) are the thickest first MTPJ ligaments. They protect the sesamoids from subluxation when high tensile forces act upon them while walking or running.

- Metatarsosesamoid ligaments (MTSLs), or suspensory ligaments, are part of the plantar plate complex. They assist with stabilising the sesamoids.

- Medial and lateral metatarsophalangeal ligaments (collateral ligaments) attach at the peripheral sesamoids. They are not part of the plantar plate complex but play an essential role as static stabilisers when applying valgus or varus forces.

Muscles[edit | edit source]

The following muscles act on the first MTP joint: tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, peroneus longus, flexor hallucis longus, extensor hallucis brevis, abductor hallucis, flexor hallucis brevis, adductor hallucis, dorsal interossei, and aponeurosis plantaris.

The muscle responsible for the motion control at the first MPJ is extensor hallucis brevis, abductor hallucis, flexor hallucis brevis, and adductor hallucis. The abductor hallucis contributes to the abduction and flexion of the first MPJ. In addition to the foot's intrinsic muscles, the flexor hallucis longus contributes to the flexion of the distal phalanx of the hallux and the extensor hallucis longus to its extension.[6]

Motion[edit | edit source]

The primary motion of the metatarsophalangeal joint is flexion and extension with minimal abduction and adduction. The collateral ligaments limit mediolateral movement in the joint.[7]

Hallux Valgus Angle[edit | edit source]

- The angle created between the lines that longitudinally bisect the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal.

- Less than 15° is considered normal. Angles of 20° and greater are considered abnormal. An angle of 45-50° is considered severe.

Epidemiology and Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Hallux Valgus deformity is a complex condition. It has a familial tendency that depends on autosomal dominant inheritance's transmission with incomplete penetrance.[2] Other aetiologic factors include the following:

- Gender (more common in women than men (ratio of 15:1)[8]

- Footwear (tight, pointed shoes)

- Menz et al. found that wearing constrictive footwear "between the ages of 20 and 39 years may be a critical period for the development of hallux valgus in later life"[9]

- Congenital deformity

- Anatomical and biomechanical factors, such as

- long first metatarsal

- rounded joint

- metatarsus primus varus

- Chronic Achilles tendon tightness

- Severe flatfoot

- Hypermobility of the first metatarsocuneiform joint

- Systemic disease

- Abnormal muscle insertions

- Hip and knee osteoarthritis[10][11][12][13]

- High Body Mass Index (BMI)

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Biomechanical Factors[2][edit | edit source]

Hallux valgus pathology is consistent with bone deviation and destabilisation of the muscle group around the joint. The following process may occur in stages or parallel:

- Initial injury relates to the failure of the medial sesamoid and the medial collateral ligaments

- Medial deviation of the first metatarsal head

- Valgus deformity of the proximal phalanx while its base is fixed to the sesamoid, transverse ligament and adductor hallucis tendon

- The lateral arching of the extensor and flexor hallucis longus tendons increases valgus deformity

- The adductor hallucis tendon pulls the phalanx in pronation, causing dislocation of the phalanx base

- First metatarsophalangeal joint rotates medially with pronation and becomes unstable

The end result is lateral deviation and lateral rotation of the hallux with medial deviation and lateral rotation of the first metatarsal.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Joint inflammation

- Initial pain and tenderness of the bunion with footwear

- Alteration in the skin over the bunion: it becomes hard, warm and red

- Bony enlargement of the first metatarsal head[15]

- Progression in pain as the bunion size increases

- Gait deviations in the midstance (middle stage) and the propulsion phase (late stance).

- As the bodyweight moves forward on a foot on the ground, the patient will tend to keep their weight on the lateral border of the foot

- Lateral and posterior weight shift

- Late heel rise due to body weight shifted on the lateral border of the foot

- Reduced time in single-limb support [16]

- Foot pronation deformity

- Weakness of hallux abductor muscles[16]

- Shortening of flexor hallucis brevis muscle

Pre-operative Management[edit | edit source]

- Patient education regarding recovery time

“I think it would be useful if you know of a patient that is thinking about having the surgery, discuss it with them, give them the stuff to read and make sure that they understand what they are letting themselves in for.” Helene Simpson [17]

Operative Treatment[edit | edit source]

Despite many surgical procedures for treating hallux valgus, no single method can correct all deformities.[4] The surgeons decide about the type of procedure based on the results of their assessment which includes:

- Close observation for an increased hallux valgus angle

- Increased intermetatarsal (IM) angle

- Pronation of the first toe

- Increased distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA)

- Enlarged medial eminence

- Subluxation of the sesamoids

Goals:

- To maintain a flexible first MTP joint

- To preserve the normal weight-bearing pattern of the forefoot

Outcomes:

- According to a study by Hernandez-Castillejo et al.,[18] hallux valgus surgery decreased patient perception of pain and increased Quality of Life in the physical and social domains

- Goh et al.[19] concluded that age did not influence the perioperative, functional, or subjective outcomes following hallux valgus surgery, but older patients may be at higher risk of recurrence

Post-operative Management[edit | edit source]

General Guidelines:

- At least six weeks of non-weight bearing

- Immobilisation in a modified shoe

- Oedema management

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Look at the patient as a WHOLE: "fix the gait, check on the foot core, plantar push-off, shoe wear, make sure you address the pain, look at the whole kinetic chain and make sure you also match it to the shoes at the bottom." Helene Simpson [17]

Fixing Gait[edit | edit source]

After hallux valgus correction, patients may adopt the habit of walking on the side of their foot to avoid loading the recently operated big toe. This needs to be addressed to ensure good balance and stability and to prevent other injuries in the long term.[20]

Goal:

- To restore gait as closely as possible back to normal

Strategies:

- Look, film, address, correct. Repeat as necessary to ensure the patient's confidence in their gait

- Facilitate loading the first metatarsal

- Walk with a patient, one foot directly in front of the other

- Forefoot mobilisation strategies, including plantar fascia lengthening, Achilles tendon lengthening

Check the Foot Core[edit | edit source]

Targeted muscles for strengthening are:[21]

- the intrinsics: abductor hallucis, adductor hallucis, and the flexor hallucis brevis

- the extrinsics: tibialis posterior and fibularis longus

Goal:

- To strengthen the foot core

Strategies:

- Ask the patient to create a dome with their foot from a seated position by pressing the toes down and shortening the foot with isometric holds.

- Ask the patient to press the first toe down and lift the other four toes, then switch around, push the four toes down and lift the big toe.

- Add some resistance using an exercise band (put the band underneath and press down on it while pulling the band up with both hands). This exercise is called 'foot core plus'.

- Ask the patient to do the same exercise while maintaining the foot dome. A further step would be to get the toes down, the first ray down, and then they can start lifting the heel all the time, maintaining a good foot posture.

- Progress into standing, standing on one foot, walking, stepping up, stepping down.

Planter Push-Off[edit | edit source]

Goal:

- To improve the functional push-off

Strategies:

- Exercises

- Standing over the edge of a box or a step with an exercise band - ask the patient to push through the band.

- Walking with an exercise band underneath the toes and pulling it up - the patient pushes their toes down into the band as they walk, pressing down to push their foot off.

- Soft tissue work is also essential, such as releasing the toe extensors. These muscles get stiff and lose the ability to slide smoothly through the extensor retinaculum in line with the syndesmosis.

- Heel raises to strengthen the plantar flexors, and if they are tight, it is helpful to lengthen, release and stretch them by asking the patient to stand over the edge of a step and to drop their heels down. You can put cotton wool between the toes to stretch them.

- Second toe mobility and flexibility

Address the Pain[edit | edit source]

Goal:

- To reduce pain and restore normal toe and foot joint range of motion and muscle length

Strategies:

- Desensitising techniques

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- Medication review with the surgeon and the patient

- Therapists need a good understanding of surgical techniques to avoid using techniques that could disturb bone healing, such as mobilising a scarf osteotomy

- Sesamoid mobilisation: grade III joint mobilisations on the medial and lateral sesamoid of the affected first MPJ.

- One thumb is placed on the proximal aspect of the sesamoid and is used to apply a force from proximal to distal that causes the sesamoid to reach the end range of motion (distal glides). These are performed with large-amplitude rhythmic oscillations. No greater than 20° of movement of the MPJ should be allowed during the technique.[24] NOTE: Always check operative protocol before choosing intervention. This technique is not suitable if a surgical procedure with fusion has been done.

Match the Shoe[edit | edit source]

Goal:

- To provide needed support for sensitive and swollen foot

Strategies:

- Ask the patient what shoes they see themselves wearing

- Assess the shoe the patient is currently wearing

- The worn shoe may no longer be suitable - its shape may have changed to accommodate the pre-operative foot posture

- A wider toe box and sound, solid heel structure can be useful

- Do not wear flat leather sole shoes

- Wearing silk socks or silky stockings can prevent friction and protect the scar

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mortka K, Lisiński P. Hallux valgus-a case for a physiotherapist or only for a surgeon? Literature review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Oct;27(10):3303-7

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Cavalheiro CS, Arcuri MH, Guil VR, Gali JC. HALLUX VALGUS ANATOMICAL ALTERATIONS AND ITS CORRELATION WITH THE RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS. Acta Ortop Bras. 2020 Jan-Feb;28(1):12-15.

- ↑ Wojcik B, Fabiś M, Zadroźna K, Małek A, Iwaniszyn-Zapołoch K, Remjasz K,Aleksandrowicz J, Siedlecki W. Hallux valgus treatment and new methods. Journal of Education, Health and Sport [online]. 2022;12( 9): 614–620. [last access 18.02.2023]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Joseph TN, Mroczek KJ. Decision making in the treatment of hallux valgus. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(1):19-23.

- ↑ Hallinan JTPD, Statum SM, Huang BK, Bezerra HG, Garcia DAL, Bydder GM, Chung CB. High-Resolution MRI of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint: Gross Anatomy and Injury Characterization. Radiographics. 2020 Jul-Aug;40(4):1107-1124.

- ↑ J.S. Kawalec JS. 12 - Mechanical testing of foot and ankle implants. Editor(s): Friis E. Mechanical Testing of Orthopaedic Implants. Woodhead Publishing 2017: pages 231-253

- ↑ Mojica MN, John S. Early JS.19 - Foot Biomechanics. Editor(s): Webster JB, Murphy DP. Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices (Fifth Edition),Elsevier, 2019: 216-228.e1.

- ↑ Kakwani M, Kakwani R. Current concepts review of hallux valgus. Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery. 2021;8(3):222-30.

- ↑ Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M, Thomas MJ, Rathod T, Peat GM, Croft PR. Epidemiology of shoe wearing patterns over time in older women: associations with foot pain and hallux valgus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Dec;71(12):1682-7.

- ↑ Hannan MT, Menz HB, Jordan JM, Cupples LA, Cheng C-H, Hsu Y-H. Hallux Valgus and Lesser Toe Deformities are Highly Heritable in Adult Men and Women: the Framingham Foot Study. Arthritis care & research. 2013;65(9):1515-1521.

- ↑ Golightly YM, Hannan MT, Dufour AB, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Factors Associated with Hallux Valgus in a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study of Adults with and without Osteoarthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(6):791-798.

- ↑ Barnish MS, Barnish J. High-heeled shoes and musculoskeletal injuries: a narrative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010053

- ↑ Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M, et al. Epidemiology of Shoe Wearing Patterns Over Time in Older Women: Associations With Foot Pain and Hallux Valgus. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2016;71(12):1682-1687.

- ↑ Biomechanix Foot and Knee Clinic. Hallux Valgus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_orU3MgOVw [last accessed 08/01/17]

- ↑ Menz HB, Munteanu SE. Radiographic validation of the Manchester scale for the classification of hallux valgus deformity. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 Aug;44(8):1061-6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Dimonte P, Light H. Pathomechanics, gait deviations, and treatment of the rheumatoid foot: a clinical report. Phys Ther. 1982 Aug;62(8):1148-56.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Simpson H. Hallux Valgus. Plus Course 2020

- ↑ Hernández-Castillejo LE, Martínez Vizcaíno V, Garrido-Miguel M, Cavero-Redondo I, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Álvarez-Bueno C. Effectiveness of hallux valgus surgery on patient quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Orthop. 2020 Aug;91(4):450-456.

- ↑ Goh GS, Tay AY, Thever Y, Koo K. Effect of age on clinical and radiological outcomes of hallux valgus surgery. Foot & Ankle International. 2021 Jun;42(6):798-804.

- ↑ Schuh R, Hofstaetter SG, Adams SB Jr, Pichler F, Kristen KH, Trnka HJ. Rehabilitation after hallux valgus surgery: importance of physical therapy to restore weight bearing of the first ray during the stance phase. Phys Ther. 2009 Sep;89(9):934-45.

- ↑ Glasoe WM. Treatment of progressive first metatarsophalangeal hallux valgus deformity: a biomechanically based muscle-strengthening approach. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jul;46(7):596-605.

- ↑ Align Therapy. Strengthening the Foot Core! Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmqBTq3HIJw [last accessed 24/02/2023]

- ↑ Northwest Foot & Ankle. Toe Extensor Stretch with Dr Ray McClanahan. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2kaEOd3GcI [last accessed 24/02/2023]

- ↑ Shamus J, Shamus E, Gugel RN, Brucker BS, Skaruppa C. The effect of sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training on reducing pain and restoring function in individuals with hallux limitus: a clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Jul;34(7):368-76.