Fitness and Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

.The relationship between flexibility and lower back pain, however, is still largely based around theory and there are yet to be a number of high-quality experiments/investigations to either support or refute this hypothesis. | .The relationship between flexibility and lower back pain, however, is still largely based around theory and there are yet to be a number of high-quality experiments/investigations to either support or refute this hypothesis. | ||

== | == Conclusions == | ||

A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain concluded thus | |||

A | A general exercise programme that combines muscular strength, flexibility and aerobic fitness is beneficial for rehabilitation of non-specific chronic low back pain. Increasing core muscular strength can assist in supporting the lumbar spine. Improving the flexibility of the muscle-tendons and ligaments in the back increases the range of motion and assists with the patient’s functional movement. Aerobic exercise increases the blood flow and nutrients to the soft tissues in the back, improving the healing process and reducing stiffness that can result in back pain.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 06:16, 1 February 2022

Original Editor - Peter Copeland, George Smith, Bryn Roberts as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Peter Copeland, George Smith, Lucinda hampton, Bryn Roberts, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Fahad Bin Aftab, Admin, Shaimaa Eldib and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is an umbrella of conditions with 80% of adults estimated to experience LBP at some point during their life [1]. Low back pain refers to pain between the bottom of the ribs and the buttock crease.

- A high physical fitness level, and especially muscle endurance in the back muscles, is associated with lower risk of back pain[2]

- A harmful misconception is that exercise should be avoided when LPB is present. Understandably, many patients are reluctant to exercise out of the fear that any exercises or stretching will aggravate their existing back pain. They may become reluctant to exercise and rely on medications.[3]

- Physical activity (PA) to increase aerobic capacity and muscular strength, especially of the lumbar extensor muscles, is important for patients with chronic LBP in assisting them to complete activities of daily living.[4]

This article focuses on non specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) and its relations with fitness.

Fitness [edit | edit source]

Physical fitness is a set of attributes that people have or achieve. Being physically fit has been defined as the ability to carry out daily tasks with vigour and alertness, without undue fatigue and with ample energy to enjoy leisure-time pursuits and meet unforeseen emergencies[5]

The five components of physical fitness and the Gold Standards for measuring are:

- Cardiorespiratory Endurance - VO2 max per Kg of body mass [6]

- Muscular Endurance - Currently no Gold Standard measurment for muscular endurance

- Muscular Strength - Isokinetic Dynamometry [7] VO2 max normative values

- Body Composition:- The current Gold Standard is a Four-Compartment model of measurements most commonly consisting of Mass, Total Body Volume, Total Body Water and Bone Mineral Content.[8]

- Flexibility - Optical Gold Standards such as the Vicon Motion Tracking System[9]

Cardiorespiratory Endurance[edit | edit source]

Aerobic exercise stimulated the cardiovascular system. Aerobic exercise can benefit CLBP as it increases the blood flow and nutrients to the soft tissues in the back, improving the healing process and reducing stiffness that results in back pain. 30–40 min of aerobic exercise increases the body’s production of endorphins. Increasing the body’s endorphin production is a natural alternative for pain relief for the body and can reduce CLBP. Rehabilitation involving aerobic exercise are a conservative method for reducing CLBP, and could prevent patients relying on medication for pain reduction.

- A low aerobic fitness level is associated with CLBP

- Maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) is found to be significantly lower by 10 mL/kg in men and by 5.6 mL/kg in women with CLBP compared to men/women without.

Smokers have a higher rates of CLBP due in part to a decreased in arterial oxygen to the core muscles, leading to muscle fatigue and pain.[10]

Muscular Endurance [edit | edit source]

Muscular Endurance is the ability of the muscle to exert a submaximal force repeatedly over a sustained period of time.

- Patients with low back pain have reduced lumbar extensor muscular endurance in comparison with non-sufferers.[11] [12]See Biering-Sorenson Test.

- Abdominal muscular endurance in low back pain sufferers is significantly decreased in contrast to those in the normal health population [13]

- Lumbar fatigue as a result of low muscular endurance has been shown to reduce the person’s ability to sense the positioning of the lumbar spine and that 25% of people with chronic LBP (n=57) had severely impaired ability in controlling the position of the lumbar spine after a fatiguing task.[14]

- Physiologically in patients with lower back pain, it has been shown they have a higher percentage of fast type I glycolytic fibres compared to the slow oxidative fibres, this can be expected to render them less resistant to fatigue, where-as non-LBP people have a much higher percentage of type II glycolytic fibres giving them better muscular endurance helping prevent lower back pain.[15]

Strength and Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

The core is the group of trunk and hip muscles that surround the spine, abdominal viscera and hip. Core muscles are essential for proper load balance within the spine, pelvis, and kinetic chain. Core strengthening has a strong theoretical basis in treatment and prevention of LBP, as well as other musculoskeletal afflictions. A reduction in core strength can lead to lumbar instability.[3] Muscle strengthening exercises form part of the NICE treatment guidelines for Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain.

The importance of the core relate to its function ie sparing the spine from excessive load and transfer force from the lower body to the upper body and vice versa.

- Having a strong, stable core helps us to prevent injuries and allows us to perform at our best.

- In order to protect the back, ideally we want to create 360 degrees of stiffness around the spine as we move, run, jump, throw, lift objects and transfer force throughout our body.

- We do this when all of the muscles in our hips, torso and shoulders work together[16]

- Exercises to activate the deep abdominal muscles including the superficial muscles, transversus abdominis muscle and the multifidus are important for CLBP patients[3].

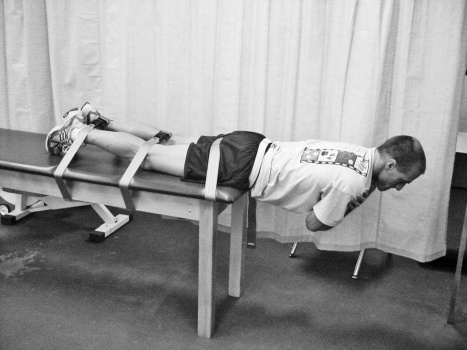

Measures of Back Strength: For information here look at Physiotherapy Assessment section of Core Stability

Few of us will have access to a isokenetic machine to measure trunk strength, as shown in video below.

| [17] |

Body Composition [edit | edit source]

The body is composed of water, protein, minerals, and fat. A two-component model of body composition divides the body into a fat component and fat-free component. Body fat (storage fat) in excess can increase susceptibility to chronic illness, health complications, and LBP. Numerous studies have been conducted highlighting the relationship between increased fat content and the likelihood/prevalence of lower back pain.

- A study conducted in 2003 [18] found that there was a moderate positive relationship between obesity and lower back pain, however the results were based on the BMI calculation which does not definitively measure body fat content.

- In a study conducted by Urquhart 2011 which took into account the amount of body storage fat[19] and it was evident that there was a relationship between obesity and lower back pain

It is the common belief that an increase in body weight alters spinal biomechanics and loading, creating excess strain to be put through certain structures eg Obesity can lead to altered body positions such as exaggerated lumbar lordosis which will cause an alteration in spinal loading mechanics.

Flexibility[edit | edit source]

Stretching the soft tissues in the back, legs and buttock eg hamstrings, erector muscles and hip flexor muscles, ligaments and tendons can help to mobilise the spine, and improve the range of motion of the spine, decreasing back pain.

An improved range of motion assists with ability to complete activities of daily living eg lifting and bending which require trunk flexion, a complex interaction combining lumbar and hip motion[3]. Spasmodic or shortened back muscles adversely affect the complex spinal mechanics [20].

- Stretching exercises decrease the muscle stiffness as a result of changes in viscoelastic properties, due to the decreased actin-myosin cross-bridges and the reflex muscle inhibition.[3]

- Tightness in the hip flexors and hamstrings can lead to a Lumbar hyperlordosis, predisposing patients to lumbar facet sydnrome[21]

.The relationship between flexibility and lower back pain, however, is still largely based around theory and there are yet to be a number of high-quality experiments/investigations to either support or refute this hypothesis.

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain concluded thus

A general exercise programme that combines muscular strength, flexibility and aerobic fitness is beneficial for rehabilitation of non-specific chronic low back pain. Increasing core muscular strength can assist in supporting the lumbar spine. Improving the flexibility of the muscle-tendons and ligaments in the back increases the range of motion and assists with the patient’s functional movement. Aerobic exercise increases the blood flow and nutrients to the soft tissues in the back, improving the healing process and reducing stiffness that can result in back pain.[3]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Palmer KT, Walsh K, et al. Back pain in Britain: comparison of two prevalence surveys at an interval of 10 years BMJ 2000

- ↑ E spine Exercise and Fitness to Help Your Back Available:https://www.spine-health.com/wellness/exercise/exercise-and-fitness-help-your-back (accessed 1.2.2022)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Andersen LB, Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C. Association between back pain and physical fitness in adolescents. Spine. 2006 Jul 1;31(15):1740-4.Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16816772/ (accessed 1.2.2022)

- ↑ Gordon R, Bloxham S. A systematic review of the effects of exercise and physical activity on non-specific chronic low back pain. InHealthcare 2016 Jun (Vol. 4, No. 2, p. 22). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4934575/ (accessed 21.2.2022)

- ↑ President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports: Physical Fitness Research Digest. Series 1,No.1, Washington DC,1971.

- ↑ Mota, Jorge, et al. "Association of maturation, sex, and body fat in cardiorespiratory fitness." American Journal of Human Biology 14.6 (2002): 707-712.

- ↑ Stark, Timothy, et al. "Hand-held dynamometry correlation with the gold standard isokinetic dynamometry: a systematic review." PM&R 3.5 (2011): 472-479.

- ↑ Wilson, J. P., Mulligan, K., Fan, B., Sherman, J. L., Murphy, E. J., Tai, V. W., ... & Shepherd, J. A. (2012). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry–based body volume measurement for 4-compartment body composition. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 95(1), 25-31.

- ↑ Mohamed, Abeer A., et al. "Comparison of Strain-Gage and Fiber-Optic Goniometry for Measuring Knee Kinematics During Activities of Daily Living and Exercise." Journal of biomechanical engineering 134.8 (2012).

- ↑ Power, C., Frank, J., Hertzman, C., Schierhout, G., & Li, L. (2001). Predictors of low back pain onset in a prospective British study. American Journal of Public Health, 91(10), 1671-1678.

- ↑ Andersen, J. S. (2007). Physical fitness and low back pain: Performance-based and self-assessed physical fitness as risk indicator of low back pain among health care workers and students. Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Arbejdsmiljø; Københavns universitet. Det Sundhedsvidenskabelige fakultet.

- ↑ Biering-Sorenson, F. (1984). Physical measurements as risk indicators for low back trouble over a one-year period. Spine, 9, 106-119.

- ↑ Foster, D. N. & Fulton, M. N. (1991). Back pain and the exercise prescription. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 10, 187-209.

- ↑ Taimela, S., Kankaanpää, M., & Luoto, S. (1999). The effect of lumbar fatigue on the ability to sense a change in lumbar position: a controlled study. Spine, 24(13), 1322.fckLRChicago (lumbar positioning)

- ↑ Mannion, A. F., Weber, B. R., Dvorak, J., Grob, D., & Müntener, M. (1997). Fibre type characteristics of the lumbar paraspinal muscles in normal healthy subjects and in patients with low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 15(6), 881-887.

- ↑ Physiopedia Core Stability Available:https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Core_Stability&utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=related_articles&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal (accessed 1.2.2022)

- ↑ Isokinetic System Con-Trex. 08 Isokinetic measurement trunk on Con-Trex TP trunk module.mov. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEhLr5y0wBE [last accessed 29/11/15]

- ↑ Bener, A., Alwash, R., Gaber, T. and Lovasz,G. 2003. Obesity and Low Back Pain. Coll. Antropol. 27 (2003) 1: 95–104

- ↑ Urquhart, D.M. 2011, Higher Body Fat Linked to Increased Back Pain. Spine 9/1/2011 Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia

- ↑ Farfan, H. F. (1975). Muscular mechanism of the lumbar spine and the position of power and efficacy. Orthopaedic Clinics of North American, 6, 135-144.

- ↑ Swedan, N. (2001) Women's Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, UK.