Extensor Tendon Injuries of the Hand

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (22/09/2020)

Original Editors - Sofie Christiaens as as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk, Sofie Christiaens, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Andeela Hafeez, Admin, WikiSysop, Tarina van der Stockt, Shaimaa Eldib, Mariam Hashem, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Claire Knott, Jess Bell, Anas Mohamed, 127.0.0.1 and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

An extensor tendon injury is a cut or tear to one of the extensor tendons. Due to this injury, there is an inability to fully and forcefully extend the wrist and/or fingers.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Extensor tendons of the hand lie very superficially and the soft tissue covering the tendons is very thin.[1] This makes these tendons susceptible to injuries such as lacerations or open injuries.[1] Another reason is the lack of subcutaneous tissue between the tendons and the overlying skin.[2]

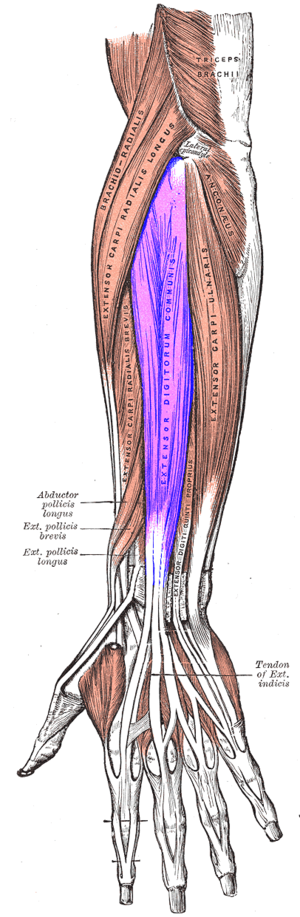

Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC)[edit | edit source]

- main extensor tendon of the hand[3]

- centrally placed in the posterior compartment of the forearm

- Origin:

- the lateral epicondyle of the humerus via the common extensor tendon, the covering fascia and the intermuscular septa at its sides. In the lower part of the forearm the muscle forms four tendons. These tendons pass deep to the extensor retinaculum. On the dorsum of the hand the tendons diverge towards the medial four digits

- Insertion:

- Each tendon helps to form an aponeurosis over the dorsum of the hand – the dorsal digital expansion or extensor hood. It has been suggested to think about the extensor hood as a "moveable triangular hood." The base lies proximally over the metacarpophalangeal joint. Then the sides of the hood wrap around the phalanx. At the proximal interphalangeal joint the hood is reinforced by the interosseus and lumbrical muscles. At the distal end of the proximal phalanx the extensor hood divides into three parts. The central part inserts onto the base of the middle phalanx on the dorsal aspect. The two collateral parts reunite to insert onto the dorsal aspect of the base of the distal phalanx.

- Innervation:

- Posterior interosseus branch of the radial nerve

- Action:

- The primary action is extension of the metacarpophalangeal joints.

- It also helps to extend both interphalangeal joints.[3]

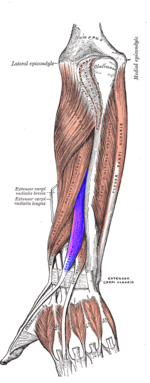

Extensor Pollicis Longus (EPL)[edit | edit source]

- Lies deep to the extensor digitorum in the posterior compartment of the forearm[3]

- Origin:

- Lateral part of the middle third of the posterior surface of the ulna and the adjacent interosseus membrane

- Insertion:

- At the dorsal surface of the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb

- Innervation

- Posterior interosseus branch of the radial nerve

- Action:

- Extends all of the joints of the thumb.

- Also assists in extension and abduction of the wrist[3]

Tendon Zones[edit | edit source]

Extensor tendons are located at the dorsal region of the hand and fingers. The function of these tendons is to extend the wrist and the fingers. According to Kleinert and Verdan (1983), there are eight anatomic zones in which the extensor mechanism of the fingers and wrist is divided.[4][5][6] Odd numbered zones refer to injuries over the joints and the even number zones refer to the segments between two joints.[1]

- Zone I: DIP joint

- Zone II: middle phalanx

- Zone III: PIP joint

- Zone IV: proximal phalanx

- Zone V: MCP joint

- Zone VI: metacarpals

- Zone VII: wrist (carpus and extensor retinaculum)

- Zone VIII: distal third of the forearm[6][7]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

- more than 50% of acute tendon trauma injuries are extensor tendon injuries[8]

- reported incidence of 14 cases per 100 000 person-years[8]

- extensor tendon injuries represent 16,9% of orthopaedic soft tissue injuries[9]

- common injury in young manual workers[10]

- mostly men in their 30's as they are the working age group[11]

- dominant hand more likely to be injured

- in the UK - these injuries represent up to 30% of all emergency department visits[12]

- in the USA - estimated to comprise more than 25% of all soft tissue injuries[13]

Mechanism of injury[edit | edit source]

- Open wounds[9]

- Often open wound that needs urgent medical attention and patients present at the hospital

- Direct lacerations by sharp objects, knifes or scissors

- Saw injuries

- Burns

- Blunt trauma

- Bites

- Crush injuries

- Avulsions

- Deep abrasions

- Closed rupture[9]

- as a result of conditions that weaken the tendon structure such as Rheumatoid Arthritis

- attrition by internal hardware used for bone fixation

- under situations of extreme load[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Dependent on the zone of injury, different characteristics are shown.

- Zone I: Mallet finger

- Zone II: no complete rupture of the tendon, but partially injured[5]

- Zone III: Disruption of the central slip, also called a Boutonnière deformity or jammed finger. This is characterised by a flexed position of the PIP joint and an extension or hyperextension of the DIP joint[14]

- Zone IV: injuries are frequently partial, with or without loss of extension at the PIP joint[7]

- Zone V: fight bite injuries (open injuries) or non-fight bite injuries (e.g. blunt trauma): a possible effect of such an injury is a rupture of the sagittal bands, attended with following extensor tendon subluxation[7]. This is presented as a difficulty to actively straighten the flexed MCP joint[5]

- Zone VI: the MCP joint can still be extended via the juncturae tendinum

- Zone VII: physical injury to the extensor retinaculum[7]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Mallet Finger[10]

- refers to a drooping end-joint of a finger.

- This happens when an extensor tendon has been cut or torn from the bone. It is common when a ball or other object strikes the tip of the finger or thumb and forcibly bends it.

- Boutonnière Deformity[10]

- describes the bent-down (flexed) position of the middle joint of the finger. Boutonniere can happen from a cut or tear of the extensor tendon.

- Cuts on the back of the hand

- can injure the extensor tendons. This can make it difficult to straighten your fingers

- Trigger finger[10]

- no passive movement possible

- Posterior Interosseus nerve (PIN) syndrome[10]

- patient unable to extend actively, but tenodesis remain normal

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Radiographs are recommended because associated injuries of surrounding structures are common. For example, it can be that a piece of bone is pulled off with the tendon[7]. X-rays may rule out or confirm associated bone injuries.[9]

- Ultrasound - high resolution ultrasound is considered to be reliable and useful diagnostic tool in the detection of tendon injuries[15]

- MRI has high diagnostic value to assess tendon injuries of the hand and may be helpful in the diagnosis of extensor tendon injuries[16]

- Clinical tests[17]

- Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC):

- hand in hook position, with PIP and DIP joints flexed, ask patient to actively extend the MCP joints

- Extensor Pollicis Longus (EPL):

- patient rests hand on the table and lift thumb of the table. If EPL laceration- significant smaller movement and won’t be able to extend their IP joint of the thumb

- Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC):

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire (DASH)

- Quick DASH –This outcome measure is a shortened version of the DASH and is used to determine the patient’s physical function and symptoms[18]

- Gartland and Werley Score – This is one of the most widely used outcome measures used in the clinic to evaluate wrist and hand function.

- Sollerman Hand Function Test (SHFT)[18]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Examination of extensor tendon injuries contains different points of interest. First, the wound characteristics should be evaluated e.g.such as size and location to give the physical therapist has an idea of which structures may have been damaged. Next, the function of the fingers and wrist will be tested in three ways: passively, actively and then with resistance. It is important that each finger is tested separately because the juncturae tendinum between the communis tendons can mask a dysfunction. Furthermore, complete neurovascular examinations should be done.

Specific for zone III injuries, the Elson test can be used[7].

| [19] |

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Patients with an extensor tendon injury can be treated in two ways, surgically or conservatively (namely splinting). The choice of treatment depends on the degree of the injury. In general, open injuries and entire ruptures demand surgical treatment. Closed injuries and partial lacerated tendons require splinting,[20]

Static as well as dynamic splinting is used. The mechanism of the dynamic splint is based on the withdraw of elastic bands, in contrast with the static splint where there is no load on the joints[21].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Preferably same day surgery

- Primary repair

- Tendon transfer (for example extensor indices transfer to EPL) is an option in cases where:

- There is a delay between the time of injury and time of surgery

- The tendon is too frayed

- The tendon is too short

Post-surgical Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

It is important to see patients as soon as one to five days postoperatively for the best possible outcome.

Wound care and Scar Management[edit | edit source]

- Provide wound care – keep the wound dry and clean and monitor the wound for signs of infection

- Commence scar management early to prevent adhesions

- Extensor tendons lie superficially and a scar on the dorsum of the hand may adhere quite quickly and this can restrict flexion range of motion in the fingers.

- Massage the scar and aim to keep the skin on the dorsum of the hand as mobile as possible

Oedema control[edit | edit source]

- Control swelling of the hand

- Patient should keep hand elevated to reduce and prevent swelling

- Performing the active range of motion exercises prescribed within the provided protocol will also control swelling

- Compression can be applied where needed to control swelling

Orthosis[edit | edit source]

The therapist also provides the patient with the specified splint or orthosis as well as the exercises relative to the rehabilitation protocol provided by the surgeon or therapist

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

Patient education is an important part of the postoperative management of extensor tendon injuries. It is important for patients to know the following:

- To keep the wound dry and clean

- To keep the splint in place 24/7

- To perform their exercises with their splint on, unless the therapist advised them differently

- If the splint is taken of the patient must keep their hand and forearm in the safe position to keep the tendons on no stretch. This position is the forearm in supination and the fingers relaxed. It is very important for patients to be aware of this and follow this recommendation as this will reduce the risk of tendon rupture or the extensor tendons EPL and EDC from overstretching, if they are ever out of the splint.

Rehabilitation Protocols[edit | edit source]

Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC)[edit | edit source]

Merrit Protocol[edit | edit source]

- Most popular protocol to treat zone V extensor tendon injuries (Hirth)

- Good outcomes achieved with this protocol and patients feel that they have some freedom as fingers are not immobilised

- Allows patients to use hand for very, light functional activities throughout the course of rehabilitation

- Only appropriate for use in extensor tendon injuries to the EDC in zones V to VII (from MCP joints to wrist) and only if patient has lacerated one to three tendons and had tendon repair.

- Due to the nature of the splint – this protocol cannot be used for more than three lacerated tendons

- Splint:

- Splint consists of two pieces:

- The volar wrist splint – wrist in 20°-30° of extension

- Second component is a relative motion splint for the fingers – which positions the affected finger in slight MCP extension relative to the unaffected fingers. This allows the patient to flex the MCP joints and assists with tendon glide to prevent adhesions

- Splint consists of two pieces:

Merrit Protocol Exercises[edit | edit source]

- All exercises are performed with the splint on

- Exercises are done 5 times a day and 10 repetitions of each exercise

- Exercises:

- Active MCP flexion

- Hook fist

- Composite flexion

- Active finger extension

- The patient does these exercises with the wrist splint and the relative motion splint on

- Patient continues with these exercises for the duration of splinting – usually about 6 weeks

- It is also important to ensure that the PIP joint is maintaining full extension within the splint.

- If a patient has an extension lag of the PIP joint – it might be useful to put the affected finger in a finger through or finger extension splint at night

- If more than one finger is involved and with a lag, a resting splint may be a good option for the patient to wear at night

- The resting splint should keep the wrist in slight extension, MCP’s in 20 – 30 degrees of flexion and the PIP and DIP joints in neutral.

- At four weeks post-operatively the wrist splint is taken of and ceased.

- The relative motion finger component is continued until 6 weeks postoperatively

- At 6 weeks postoperatively all splints are stopped

- Patient is encouraged to use hand for light functional use and full range of motion

- Passive stretching commences at 7 weeks postoperatively

- Strengthening commences at around 8 weeks postoperatively

Norwich Protocol

Often used in patients that are less reliable

If patient has had two or more tendons repaired

Surgical repair not as strong as what it could be

Used in patients with tendon lacerations of zones V – VII

Patient is initially seen on days one to four postoperatively

Therapist fabricates a volar splint with the wrist in 45 degrees extension, MCP’s flexed to 50 degrees and the IP joints extended

This is a tricky position to splint – but the IP joint extension is important to prevent any extension lags

Fabricate the splint with the patient’s forearm in supination – as this will allow the therapist to drape and mould the thermoplastic well over the hand to ensure a good wrist- extended position

Exercises in Norwich Protocol

Resting splint is worn 24/7

Exercises are performed with the splint on

Exercise frequency: 10 repetitions of each exercise, 5 times a day.

Exercises

1.Combined IP and MCP joint extension of the splint

2.Hook fist with splint in place

Patient continues with these exercises for 6 weeks, until patient is weaned from the splint

If there is no evident extension lag after 6 weeks, the patient can stop wearing the splint at 6 weeks

Patient is encouraged to use the hand for unlimited use

Grip strengthening is commenced at 7 weeks

At 8 weeks postoperatively, full passive flexion stretches can be commenced if full finger flexion has not yet been regained

A dynamic flexion splint may be considered at 12 weeks if it required to regain flexion

Should there be an extension lag greater than 30 degrees – the patient needs to continue wearing the splint until 8 weeks postoperatively.

Rehabilitation Protocol for Extensor Pollicis Longus

Splint used:

Volar Thermoplastic splint with the wrist in slight extension and thumb held in extension as well

Splint comes to below the MCP joints, just through the distal palmar crease of the hand and up to two thirds of the forearm

Splint also comes up to the tip of the thumb – because the EPL tendon inserts at the base of the distal phalanx and the distal phalanx should not be flexing freely

Exercises

Early active range of motion exercises should be started from the first appointment

With the splint on – the patient performs active extension

With the splint on, but the thumb strap released, with the wrist in extension, isolated IP joint flexion can be performed, as well as isolated MCP joint flexion.

Only exercise that patient may perform with splint of is gradual opposition of the thumb, BUT these exercises must be performed with the forearm in supination

Gradual opposition of the thumb to each fingertip is performed, with progression to a different finger tip each week. Week 1 – oppose the thumb to index finger. Week 2 – oppose the thumb to the middle finger, Week 3 – oppose the thumb to the ring finger, etc. Until patient is able to flex the the thumb down to the proximal crease over the MCP joint of the little finger by week 6

Exercises remain the same until 6 weeks postoperatively

After 6 weeks the patient can be weaned out of the splint

Encourage patient to use hand for full range of motion and light functional activities

Strengthening exercises are commenced at 8 weeks postoperatively if surgeon gives clearance

Strengthening exercises include using Theraputty for finger extension exercises – make a little doughnut shape out of Theraputty, place around the fingers and then actively extend the fingers.

Another example is using the Theraputty for finger flexion exercises into a full fist – as patients often lost grip strength as a result of the period of immobilisation

Red Flags in Extensor Tendon Injuries

Ruptures

This is always a concern with tendon repairs.

If a patient has ruptured the EPL – unable to extend the IP joint

EDC rupture – unable to extend MCP joints when isolate

Look out for ruptures during the first 6 weeks postoperatively, but especially within the first 3 weeks postoperatively

Extensor Lags

Extensor lags are often difficult to correct once it has developed, so it is key to identify a lag as soon as possible. In a patient with a lacerated ECD tendon and using the Merrit Protocol, who is unable to actively extend the affected finger at the PIP joint - a volar extension splint at night or for resting is recommended. If more than one finger is involved with an extensive lag at the PIP joint – a night resting splint should be considered.

Infection

Look out for any redness, pain, oozing, odorous smells around the wound site. Flag any signs of infection with the surgeon.

Key messages to remember

1.Know your Anatomy

This will inform treatment approach and inform your clinical reasoning. Know which tendon was lacerated and in what zone as the treatment protocols for the various zones differ.

Know the patient’s history

This will influence your treatment of the patient. Was the tendon cleanly cut. Was the surgery performed immediately or was there a delay? Is the patient reliable and can the therapist trust the patient to perform their exercises according to the protocol provided to them. Is the patient educated about the injury and will the patient be compliant. It is important to come up with an appropriate treatment protocol in conjunction with the surgeon to best treat the individual patient.

Be confident in your splinting skills

Practice before you fabricate a splint for the first time, especially with the relative motion splint in the Merrit Protocol. Be familiar with the degrees of the angles of the different joints that you need to place them in.

Monitor patient progress

Monitor patient progress closely and check the tendon status and look out for extension lags

Know your rehabilitation protocol

Be familiar with the selected protocol. Educate your patient and be a good teacher. Give them the confidence to manage their injury and a good outcome will be achieved.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist’s task is to improve the functionality of the hand, with the intention of achieving the pre-injury condition[22]. This will be done by gradually enlarging the range of motion. To reach the best effects, it is necessary adapting the rehabilitation program to the individual[5].

The three most common postoperative treatments are immobilisation, early controlled mobilisation and early active mobilisation[23].

1. Immobilisation[edit | edit source]

During the first three weeks, the wrist is splinted in at least 21°-45° extension with the MCP joints at 0°-20° flexion and the IP joints in neutral position[22]. This period of immobilisation is followed by passive and active movement of the affected zones[20].

Benefits of this method: a reduction of the risk of rupture, because any load is avoided.

Disadvantages: the following rehabilitation can be complicated due to extension lags, extrinsic tightness, adhesions and so on, caused by the immobilisation[21].

2. Early controlled mobilisation[edit | edit source]

A dynamic splint is used, so that the passive motion is caused by the resistance of the elastic bands. Moreover, controlled passive exercises should be done.

Benefits: support of the passive glide of the repaired tendon + protection against excessive load

Disadvantages: unpleasant to wear + expensive to construct[21]

3.Early active mobilisation[edit | edit source]

The patient wears a static splint and in the mean time, active exercises, such as bending and extending the joints should be done.

Benefits: stimulation of the gliding + decreasing of the risk of adhesions[21]

4. Comparison of the three protocols[edit | edit source]

At short notice, early controlled therapy has better outcomes in total active movement and grip strength compared to immobilisation. However, over a longer time frame, both protocols present similar results (Mowlavi et al. 2005)[21]. In this study, only the effects on injuries of zones V and VI are explored. Similar effects were found in zones I and II (Soni et al. 2009)[4].

Moreover, early active motion provides the same findings as early passive motion. The choice of protocol is based on the patient’s cooperation and on the prognosis. In cases where the patient is motivated to complete the therapy and where a quicker recovery is essential, dynamic mobilisation is preferred[22].

Important to know is that there is a paucity of high-level evidence regarding the management of extensor tendon injuries. As a result, objectively measuring the results isn’t possible. Further investigation is necessary. (Hall, B. et al. Comparing three postoperative treatment protocols for extensor tendon repair in zones V and VI of the hand: level B)[21].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Yoon AP, Chung KC. Management of acute extensor tendon injuries. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2019 Jul 1;46(3):383-91.

- ↑ Saini N, Sharma M, Sharma VD, Patni P. Outcome of early active mobilization after extensor tendon repair. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2008 Jul;42(3):336.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Palastanga NP, Field D, Soames R. Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. 5th Edition. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann, Elsevier. 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brotzman S.B., Manske R.C. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: An Evidence-Based Approach, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011 (level B)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Milner C, Russell P. Focus on extensor tendon injury. British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hirth MJ, Howell JW, Feehan LM, Brown T, O'Brien L. Postoperative hand therapy management of zones V and VI extensor tendon repairs of the fingers: An international inquiry of current practice. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2020 Mar 9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Matzon JL, Bozentka DJ. Extensor tendon injuries. The Journal of hand surgery. 2010 May 1;35(5):854-61.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 de Jong JP, Nguyen JT, Sonnema AJ, Nguyen EC, Amadio PC, Moran SL. The incidence of acute traumatic tendon injuries in the hand and wrist: a 10-year population-based study. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2014 Jun 1;6(2):196-202.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Colzani G, Tos P, Battiston B, Merolla G, Porcellini G, Artiaco S. Traumatic extensor tendon injuries to the hand: clinical anatomy, biomechanics, and surgical procedure review. Journal of hand and microsurgery. 2016 Apr;8(1):2.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Moore A, Marappa-Ganeshan R. Hand Extensor Tendon Lacerations. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Feb 4. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Amirtharajah M, Lattanza L. Open extensor tendon injuries. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2015 Feb 1;40(2):391-7.

- ↑ Miranda BH, Spilsbury ZP, Rosala-Hallas A, Cerovac S. Hand trauma: a prospective observational study reporting diagnostic concordance in emergency hand trauma which supports centralised service improvements. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2016 Oct 1;69(10):1397-402.

- ↑ Dy CJ, Rosenblatt L, Lee SK. Current methods and biomechanics of extensor tendon repairs. Hand clinics. 2013 May 1;29(2):261-8.

- ↑ Geoghegan L, Wormald JC, Adami RZ, Rodrigues JN. Central slip extensor tendon injuries: a systematic review of treatments. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 2019 Oct;44(8):825-32.

- ↑ Weinreb JH, Sheth C, Apostolakos J, McCarthy MB, Barden B, Cote MP, Mazzocca AD. Tendon structure, disease, and imaging. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2014 Jan;4(1):66.

- ↑ Soni P, Stern CA, Foreman KB, Rockwell WB. Advances in extensor tendon diagnosis and therapy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Feb 1;123(2):52e-7e.

- ↑ Thorn, K. Extensor Tendon Injury Management. Course, Physioplus. 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Collocott SJ, Kelly E, Foster M, Myhr H, Wang A, Ellis RF. A randomized clinical trial comparing early active motion programs: earlier hand function, TAM, and orthotic satisfaction with a relative motion extension program for zones V and VI extensor tendon repairs. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2020 Jan 1;33(1):13-24.

- ↑ Mike Hayton. Elsons Test. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9HY0qXWUvE [last accessed 12/10/17]

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Pho C, Godges J. Extensor tendon repair and rehabilitation (level F)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Hall, B. et al. Comparing three postoperative treatment protocols for extensor tendon repair in zones V and VI of the hand. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2010; 64: 682-688 (level B)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Bhandari M. Evidence-based Orthopedics (level B)

- ↑ Talsma E. et al. The effect of mobilization on repaired extensor tendon injuries of the hand: a systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008 Dec; 89(12): 2366-2372 (level A)