Exercise Induced Asthma: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "[[Pulmonary function test" to "[[Pulmonary Function Test") |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors '''- Kaitlyn Stahl & A.J. Walsh [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's | '''Original Editors '''- Kaitlyn Stahl & A.J. Walsh [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | |||

[[File:Asthma inhaler use.png|right|frameless]] | |||

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) describes a transient and reversible contraction of bronchial smooth muscle after physical exertion that may or may not produce symptoms of [[Dyspnoea|dyspnea]], chest tightness, wheezing, and cough. (EIB, previously called Exercise-Induced [[Asthma]])<ref name=":0">Gerow M, Bruner PJ. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557554/ Exercise Induced Asthma]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls. 2020.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557554/ (accessed 6.4.2021)</ref>. | |||

* EIB occurs in 40% to 90% of people with [[asthma]] and up to 20% of those without asthma. | |||

* The benefits of regular [[Therapeutic Exercise|exercise]] for all people are well established, and activity is an integral part of a healthy lifestyle. | |||

* People suffering from EIB may avoid exertion due to symptoms of breathlessness, cough, chest tightness, and wheezing. Exercise avoidance has been shown to increase social isolation in adolescents, and it can lead to [[obesity]] and poor health. | |||

* Exercise has paradoxically been shown to improve EIB severity, [[Pulmonary Function Test|pulmonary function]], and reduce airway [[Inflammation Acute and Chronic|inflammation]] in people with asthma and EIB. | |||

* Early detection, diagnosis confirmed by the change in [[Pulmonary Function Test|lung function]] during exercise, and treatment can improve [[Quality of Life|quality of life]] and, when managed appropriately, allows patients to participate freely in exercise without limiting competition at the elite level.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== | == Epidemiology == | ||

* Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction occurs in 40% to 90% of people with asthma and up to 20% of the general population without asthma. | |||

* Elite athletes have an increased prevalence of 30% to 70%. | |||

* Exercise-induced asthma is the most common medical problem among winter Olympic athletes, especially among cross-country skiers. Nearly 50% of these athletes suffer from the condition, closely followed by short-track speed skaters at 43%<ref>The Conversation Winter Olympics: why many athletes will be struggling with asthma Available from:https://theconversation.com/winter-olympics-why-many-athletes-will-be-struggling-with-asthma-90400 (accessed 6.4.2021)</ref>. | |||

* Approximately 400 million people are projected to have asthma in 2024, with a large percentage expected to have EIB. | |||

* Annually, 250,000 people die from asthma complications<ref name=":0" />. | |||

== Cause == | |||

[[File:Pathology.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

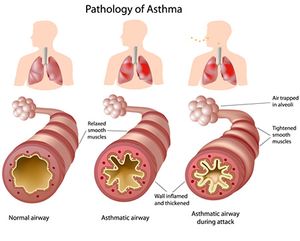

EIB is caused by an acute large increase in the amount of air entering the airways that require heating and humidifying. In susceptible individuals, this results in [[Inflammation Acute and Chronic|inflammatory,]] neuronal, and vascular changes ultimately resulting in contraction of the bronchial smooth muscle and symptoms of [[Dyspnoea|dyspnea]], cough, chest tightness, mucus production, and wheezing.<ref name=":0" />.<ref name=":1">Asthma org. EIB Available from:https://asthma.org.au/about-asthma/triggers/exercise-induced-bronchoconstriction/ (accessed 6.4.2021)</ref> | |||

Asthma is the result of complex interactions between [[Genetic Conditions and Inheritance|genetic]] predisposition and multiple [[An Introduction to Environmental Physiotherapy|environmental]] influences. The marked increase in asthma prevalence in the last 3 decades suggests environmental factors as a key contributor in the process of allergic sensitization. <ref name="Goodman">Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. W B Saunders Company; 2012. 298</ref><br>Factors that can trigger or worsen exercise-induced asthma include: | |||

* Cold air | |||

* Dry air | |||

* Air pollution such as smoke or smog | |||

* High pollen counts | |||

* Having a respiratory [[Infectious Disease|infection]] such eg [[COVID-19|COVID]] | |||

* Chemicals, such as chlorine in swimming pools.<ref name="Mayo">"Exercise-induced asthma." Mayo Clinic. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. &lt;http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/exercise-induced-asthma/basics/definition/con-20033156&gt;.</ref> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

[[File:Asthma athlete.jpeg|right|frameless]] | |||

Symptoms of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction can include mild to moderate symptoms of chest tightness, wheezing, coughing, and dyspnea that occurs within 15 minutes after 5 to 8 minutes of high-intensity [[Aerobic Exercise|aerobic training]]. Reports of severe symptoms with [[Respiratory Failure|respiratory failure]] and death occur rarely. | |||

Symptoms: | |||

* occur more often in specific environments with cold, dry air or high concentration of respiratory irritants. | |||

* usually resolve spontaneously within 30 to 90 minutes and induce a refractory period of 1 to 3 hours, where continued exercise does not produce bronchoconstriction. Patients may also be asymptomatic, and therefore EIB may be underdiagnosed. | |||

[[File:Pollution.jpeg|right|frameless]] | |||

Risk factors include: | |||

* personal or family history of asthma | |||

* personal history of atopy or allergic rhinitis | |||

* exposure to cigarette [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|smoke]], | |||

* participating in high-risk sports. High-risk sports include episodes of exercise greater than 5 to 8 minutes in certain environments (eg cold, dry air or chlorinated pools) such as long-distance running, cycling, cross country or downhill skiing, ice hockey, ice skating, high altitude sports, swimming, water polo, and triathlons. | |||

* living and practicing in areas with high levels of pollution | |||

* female gender. <ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Evaluation == | |||

[[File:Spirometry1.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

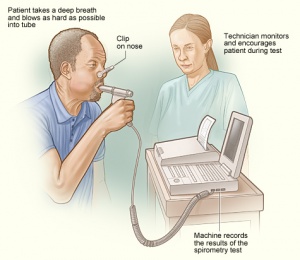

A detailed history and examination are essential and help to identify exercise as the cause of symptoms. | |||

A lung function test eg [[spirometry]]. Standardized testing for diagnosis includes direct and indirect methods and usually involves spirometry measurement of FEV1 changes from baseline expressed as a percent decrease. You may also be referred for Bronchial Challenge Testing<ref name=":1" /> eg | |||

* Direct stimulation of smooth muscle receptors by methacholine to induce bronchoconstriction is well established. Sensitivity at predicting EIB has been reported to be 58.6% to 91.1%. | |||

* Indirect testing, which is more specific for EIB, can involve aerobic exercise in a controlled environment with cold, dry air as these conditions are known to precipitate EIB in susceptible individuals. | |||

* Alternatives to exercise testing include eucapnic voluntary hyperpnea or hyperventilation of dry air, and airway provocation testing, including hyperosmolar 4.5% saline or dry powder mannitol, which act to dehydrate the [[Lung Anatomy|respiratory epithelium]] to induce EIB.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Management == | |||

<div><nowiki/>''<nowiki/>'' | |||

If addressed and treated appropriately, exercise-induced asthma should not restrict one’s ability to fully participate in vigorous [[Physical Activity|physical activity]]. Furthermore, adequate asthma control should allow for a patient to participate in any activity of choice without experiencing asthma symptoms<ref name="EPR3" />. Management of EIB should include identifying any allergens the patient may have, educating the patient on avoiding asthma triggers, and use of asthma medications, when necessary<ref name="Goodman" />. The EPR 3 Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma recommend the following treatments for the medical management of EIA<ref name="EPR3">Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Section 4, Managing Asthma Long Term—Special Situations. Accessed March 25, 2014 at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma.</ref>: | |||

<br> | '''Long-term Pharmacotherapy (if appropriate)'''<br>[[NSAIDs in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis|Anti-inflammatory medication]]<nowiki/>s, such as inhaled corticosteroids used to suppress airway inflammation, have been proven to decrease the frequency and severity of EIB when used on a daily basis for long-term control of asthma. Long-term control therapy is recommended for patients with poorly controlled symptoms, including frequent, severe episodes of EIB<ref name="EPR3" /> | ||

= | '''Treatments Prior to Exercise'''<ref name="EPR3" /> | ||

1. Inhaled beta2-agonists: | |||

| *Short Acting Beta Agonists (SABA), often called ‘rescue inhalers’, are used acutely before exercise to control symptoms up to 2-3 hours | ||

*Long Acting Beta Agonists (LABA) are used in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids to provide additional protection from asthma symptoms for up to 12 hours. LABA are not indicated for daily use but should be used as a pretreatment to exercise. | |||

2. Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists (LTRAs): are medications used for allergy treatment and to prevent asthma symptoms. LTRAs have a longer onset of action and may take hours to provide symptom relief. | |||

3. Exercise Warm Up: A period of warming up before exercise may help to decrease symptoms associated with EIB | |||

4. Protection Against Cold: Wearing a scarf over the mouth prior to/during activity may help to decrease cold-induced EIB | |||

</div> | |||

== | == Medication and Competitive Sport == | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

For elite, professional, and semi-professional athletes this is a very significant concern as the issue of drugs in sport and any medications or supplementstaken, may have serious implications. | |||

Many sporting bodies require elite, professional, and semi-professional athletes to provide evidence of EIB, such as Bronchial Challenge Test results before they are permitted to use EIB medicines during competition. So for any athlete competing at this level before you take any medication or supplement, even if prescribed by your doctor, always check with relevant authorities.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management | == Physical Therapy Management == | ||

See here too! [[Asthma]] | |||

''' | '''Education''' | ||

<br>'''Long-term Management'''<br>There are several factors that can deter patients with | As well as taking medication as prescribed the following suggestions may help some people with EIB manage their symptoms: | ||

* Warming up before exercise | |||

<br>The Preferred Practice Patterns for this patient population<ref name="Goodman 2" />, according to the Physical Therapy Guide to Practice<ref name="APTA">APTA Guide to Physical Therapist Practice-Online. Cardiovascular/Pulmonary Preferred Practice Patterns. http://guidetoptpractice.apta.org/content/current</ref>, include: | * Being as fit as possible – increasing fitness raises the threshold for EIB, so that moderately strenuous exercise may not cause an attack. | ||

* Exercising in a warm and humid environment | |||

* Avoiding environments with high levels of allergens, pollution, irritant gases or airborne particles. | |||

* Breathing through the nose to help warm and humidify the air | |||

* Using a mask to filter air, although this may be impractical or can make breathing harder | |||

* After strenuous exercise doing cooling down exercise, breathing through the nose and covering the mouth in cold, dry weather | |||

* If client smokes cigarettes, consider speaking to doctor about quitting. | |||

[[File:Exercise photo.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

'''Acute Management:'''<br>Because EIB is triggered by exercise, physical therapists may be the first to identify asthma symptoms in a patient with undiagnosed EIB. For this reason, physical therapists must be aware of the associated signs and symptoms of EIB, as well as any [[The Flag System|red flags]] that may indicate a need for medical referral and treatment. If a patient has an acute asthma attack during therapy, the physical therapist should assess the severity of the attack, then position the patient in high Fowler’s position for diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breathing, if appropriate. If the patient has an inhaler available, the physical therapist should provide assistance to allow the patient to self-administer the medication, while helping the patient to relax<ref name="Goodman 2">Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. W B Saunders Company; 2012.772-774</ref>.<br>'''Long-term Management'''<br>There are several factors that can deter patients with EIB from exercising, one being the belief that exercise is detrimental to their condition. Although there is insufficient evidence to support [[Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises|breathing]] exercises or inspiratory muscle training in patients with asthma, there is strong evidence to support the benefits of physical activity for [[Cardiovascular System|cardiovascular]] training in this patient population<ref name="Goodman 2" />. Therefore, physical therapists can play a large role in the management of care by providing patient education and exercise prescription. A study protocol will provide the effectiveness of physiotherapy on the quality of life of children with asthma<ref>Zhang W, Liu L, Yang W, Liu H. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31261560 Effectiveness of physiotherapy on quality of life in children with asthma: Study protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis]. Medicine. 2019 Jun;98(26).</ref>.<br>The Preferred Practice Patterns for this patient population<ref name="Goodman 2" />, according to the Physical Therapy Guide to Practice<ref name="APTA">APTA Guide to Physical Therapist Practice-Online. Cardiovascular/Pulmonary Preferred Practice Patterns. http://guidetoptpractice.apta.org/content/current</ref>, include: | |||

*Pattern 6B: Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Deconditioning | *Pattern 6B: Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Deconditioning | ||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

*Pattern 6E: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Ventilatory Pump Dysfunction or Failure | *Pattern 6E: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Ventilatory Pump Dysfunction or Failure | ||

*Pattern 6F: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Respiratory Failure | *Pattern 6F: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Respiratory Failure | ||

'''Exercise and Medication:''' | |||

Bronchodilators should be self-administered with a meter-dose inhaler (MDI) about 20-30 minutes prior before the patient participates in exercise. Mild stretching and a warm-up to exercise should also be performed during that time to help prevent the onset of asthma symptoms. Physical therapists must be aware of any adverse side effects or drug toxicity associated with asthma medications. Some symptoms that may suggest drug toxicity include nausea and vomiting, tremors, anxiety, tachycardia, arrhythmia, and hypotension. If the patient exhibits asthma symptoms during exercise that are not controlled with current medication, the physical therapist should notify the patient’s physician to alter the dosage<ref name="Goodman 2" />.<br>'''Vital Signs''':<br>It is important for the physical therapist to monitor the patient’s vital signs before, during and after exercise, to detect any abnormal changes in bronchopulmonary function. Auscultation of the lungs should be done routinely to detect any abnormal breath sounds, wheezing, or presence of rhonchi. Red flags that may indicate worsening asthma or drug toxicity can include tachypnea (increased respiratory rate above normative values), diarrhea, headache and vomiting. Asthma-related hypoxemia may be indicated with an abnormal rise in the patient’s blood pressure<ref name="Goodman 2" /><br>'''Other Considerations''':<br>Decreased bone mass density has been associated with long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe asthma. This chronic corticosteroid use also has an associated increased risk of fracture, in particular asymptomatic vertebral fractures. Physical therapists should be aware of the patient’s medication history and take precautions when exercising patients who may be at risk for fractures. Physical therapy can enhance medical management and play important role in the care of patients with status asthmaticus. Physical therapists can teach the patient various coughing, breathing, and positioning techniques to help clear secretions, reduce hypoxemia and improve V/Q matching. Aggressive treatments, such as forceful percussion, should be avoided in this population to prevent triggering of bronchospasms<ref name="Goodman 2" /> | |||

Bronchodilators should be self-administered with a meter-dose inhaler (MDI) about 20-30 minutes prior before the patient participates in exercise. Mild stretching and a warm-up to exercise should also be performed during that time to help prevent the onset of asthma symptoms. Physical therapists must be aware of any adverse side effects or drug toxicity associated with asthma medications. Some symptoms that may suggest drug toxicity include nausea and vomiting, tremors, anxiety, tachycardia, arrhythmia, and hypotension. If the patient exhibits asthma symptoms during exercise that are not controlled with current medication, the physical therapist should notify the patient’s physician to alter the dosage<ref name="Goodman 2" />. | |||

<br>'''Vital Signs''': | |||

<br>It is important for the physical therapist to monitor the patient’s vital signs before, during and after exercise, to detect any abnormal changes in bronchopulmonary function. Auscultation of the lungs should be done routinely to detect any abnormal breath sounds, wheezing, or presence of rhonchi. Red flags that may indicate worsening asthma or drug toxicity can include tachypnea (increased respiratory rate above normative values), diarrhea, headache and vomiting. Asthma-related hypoxemia may be indicated with an abnormal rise in the patient’s blood pressure<ref name="Goodman 2" /> | |||

<br>'''Other Considerations''': | |||

<br>Decreased bone mass density has been associated with long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe asthma. This chronic corticosteroid use also has an associated increased risk of fracture, in particular asymptomatic vertebral fractures. Physical therapists should be aware of the patient’s medication history and take precautions when exercising patients who may be at risk for fractures. Physical therapy can enhance medical management and play important role in the care of patients with status asthmaticus. Physical therapists can teach the patient various coughing, breathing, and positioning techniques to help clear secretions, reduce hypoxemia and improve V/Q matching. Aggressive treatments, such as forceful percussion, should be avoided in this population to prevent triggering of bronchospasms<ref name="Goodman 2" /> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

Symptoms of chest tightness, wheezing, coughing, and dyspnea occurring with exercise can indicate pathology along the entire airway. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is not easily diagnosed by clinical symptoms, and objective data of a decrease in lung function with exercise is required<ref name=":0" /> | |||

The most common differential diagnoses of EIB include<ref name="Schumacher">Schumacher Y, Pottgiesser T, Dickhuth H. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: Asthma in athletes. International Sportmed Journal [serial online]. December 2011;12(4):145-149. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 25, 2014.</ref>: | The most common differential diagnoses of EIB include<ref name="Schumacher">Schumacher Y, Pottgiesser T, Dickhuth H. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: Asthma in athletes. International Sportmed Journal [serial online]. December 2011;12(4):145-149. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 25, 2014.</ref>: | ||

*Vocal Cord Dysfunction | *Vocal Cord Dysfunction | ||

*Laryngeal/tracheal processes | *Laryngeal/tracheal processes | ||

*Respiratory tract infection | *Respiratory tract infection | ||

*Gastro-esophageal reflux | *[[Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease|Gastro-esophageal]] reflux | ||

*Hyperventilation syndromes | *[[Breathing Pattern Disorders|Hyperventilation]] syndromes | ||

EIB may also be associated with underlying conditions, such as<ref name="Article">Weiler JM, Anderson SD, Randolph C, et al. Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: a practice parameter. Ann. Allergy. Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(6 Suppl):S1–47. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21167465. Accessed March 25, 2014.</ref>: | EIB may also be associated with underlying conditions, such as<ref name="Article">Weiler JM, Anderson SD, Randolph C, et al. Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: a practice parameter. Ann. Allergy. Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(6 Suppl):S1–47. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21167465. Accessed March 25, 2014.</ref>: | ||

*COPD | *[[COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)|COPD]] | ||

*Obesity | *Obesity | ||

*Pectus Excavatum | *Pectus Excavatum | ||

*Diaphragmatic paralysis | *Diaphragmatic paralysis | ||

*Interstitial Fibrosis< | *Interstitial Fibrosis<u></u> | ||

</ | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Cardiopulmonary]] | |||

[[Category:Bellarmine_Student_Project]] | [[Category:Bellarmine_Student_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Chronic Respiratory Disease - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

Revision as of 14:09, 14 May 2021

Original Editors - Kaitlyn Stahl & A.J. Walsh from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kaitlyn Stahl, Andrew Walsh, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Elaine Lonnemann, Laura Ritchie, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, Vidya Acharya and Kapil Narale

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) describes a transient and reversible contraction of bronchial smooth muscle after physical exertion that may or may not produce symptoms of dyspnea, chest tightness, wheezing, and cough. (EIB, previously called Exercise-Induced Asthma)[1].

- EIB occurs in 40% to 90% of people with asthma and up to 20% of those without asthma.

- The benefits of regular exercise for all people are well established, and activity is an integral part of a healthy lifestyle.

- People suffering from EIB may avoid exertion due to symptoms of breathlessness, cough, chest tightness, and wheezing. Exercise avoidance has been shown to increase social isolation in adolescents, and it can lead to obesity and poor health.

- Exercise has paradoxically been shown to improve EIB severity, pulmonary function, and reduce airway inflammation in people with asthma and EIB.

- Early detection, diagnosis confirmed by the change in lung function during exercise, and treatment can improve quality of life and, when managed appropriately, allows patients to participate freely in exercise without limiting competition at the elite level.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction occurs in 40% to 90% of people with asthma and up to 20% of the general population without asthma.

- Elite athletes have an increased prevalence of 30% to 70%.

- Exercise-induced asthma is the most common medical problem among winter Olympic athletes, especially among cross-country skiers. Nearly 50% of these athletes suffer from the condition, closely followed by short-track speed skaters at 43%[2].

- Approximately 400 million people are projected to have asthma in 2024, with a large percentage expected to have EIB.

- Annually, 250,000 people die from asthma complications[1].

Cause[edit | edit source]

EIB is caused by an acute large increase in the amount of air entering the airways that require heating and humidifying. In susceptible individuals, this results in inflammatory, neuronal, and vascular changes ultimately resulting in contraction of the bronchial smooth muscle and symptoms of dyspnea, cough, chest tightness, mucus production, and wheezing.[1].[3]

Asthma is the result of complex interactions between genetic predisposition and multiple environmental influences. The marked increase in asthma prevalence in the last 3 decades suggests environmental factors as a key contributor in the process of allergic sensitization. [4]

Factors that can trigger or worsen exercise-induced asthma include:

- Cold air

- Dry air

- Air pollution such as smoke or smog

- High pollen counts

- Having a respiratory infection such eg COVID

- Chemicals, such as chlorine in swimming pools.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction can include mild to moderate symptoms of chest tightness, wheezing, coughing, and dyspnea that occurs within 15 minutes after 5 to 8 minutes of high-intensity aerobic training. Reports of severe symptoms with respiratory failure and death occur rarely.

Symptoms:

- occur more often in specific environments with cold, dry air or high concentration of respiratory irritants.

- usually resolve spontaneously within 30 to 90 minutes and induce a refractory period of 1 to 3 hours, where continued exercise does not produce bronchoconstriction. Patients may also be asymptomatic, and therefore EIB may be underdiagnosed.

Risk factors include:

- personal or family history of asthma

- personal history of atopy or allergic rhinitis

- exposure to cigarette smoke,

- participating in high-risk sports. High-risk sports include episodes of exercise greater than 5 to 8 minutes in certain environments (eg cold, dry air or chlorinated pools) such as long-distance running, cycling, cross country or downhill skiing, ice hockey, ice skating, high altitude sports, swimming, water polo, and triathlons.

- living and practicing in areas with high levels of pollution

- female gender. [1]

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

A detailed history and examination are essential and help to identify exercise as the cause of symptoms.

A lung function test eg spirometry. Standardized testing for diagnosis includes direct and indirect methods and usually involves spirometry measurement of FEV1 changes from baseline expressed as a percent decrease. You may also be referred for Bronchial Challenge Testing[3] eg

- Direct stimulation of smooth muscle receptors by methacholine to induce bronchoconstriction is well established. Sensitivity at predicting EIB has been reported to be 58.6% to 91.1%.

- Indirect testing, which is more specific for EIB, can involve aerobic exercise in a controlled environment with cold, dry air as these conditions are known to precipitate EIB in susceptible individuals.

- Alternatives to exercise testing include eucapnic voluntary hyperpnea or hyperventilation of dry air, and airway provocation testing, including hyperosmolar 4.5% saline or dry powder mannitol, which act to dehydrate the respiratory epithelium to induce EIB.[1]

Management[edit | edit source]

If addressed and treated appropriately, exercise-induced asthma should not restrict one’s ability to fully participate in vigorous physical activity. Furthermore, adequate asthma control should allow for a patient to participate in any activity of choice without experiencing asthma symptoms[6]. Management of EIB should include identifying any allergens the patient may have, educating the patient on avoiding asthma triggers, and use of asthma medications, when necessary[4]. The EPR 3 Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma recommend the following treatments for the medical management of EIA[6]:

Long-term Pharmacotherapy (if appropriate)

Anti-inflammatory medications, such as inhaled corticosteroids used to suppress airway inflammation, have been proven to decrease the frequency and severity of EIB when used on a daily basis for long-term control of asthma. Long-term control therapy is recommended for patients with poorly controlled symptoms, including frequent, severe episodes of EIB[6]

Treatments Prior to Exercise[6]

1. Inhaled beta2-agonists:

- Short Acting Beta Agonists (SABA), often called ‘rescue inhalers’, are used acutely before exercise to control symptoms up to 2-3 hours

- Long Acting Beta Agonists (LABA) are used in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids to provide additional protection from asthma symptoms for up to 12 hours. LABA are not indicated for daily use but should be used as a pretreatment to exercise.

2. Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists (LTRAs): are medications used for allergy treatment and to prevent asthma symptoms. LTRAs have a longer onset of action and may take hours to provide symptom relief.

3. Exercise Warm Up: A period of warming up before exercise may help to decrease symptoms associated with EIB

4. Protection Against Cold: Wearing a scarf over the mouth prior to/during activity may help to decrease cold-induced EIB

Medication and Competitive Sport[edit | edit source]

For elite, professional, and semi-professional athletes this is a very significant concern as the issue of drugs in sport and any medications or supplementstaken, may have serious implications.

Many sporting bodies require elite, professional, and semi-professional athletes to provide evidence of EIB, such as Bronchial Challenge Test results before they are permitted to use EIB medicines during competition. So for any athlete competing at this level before you take any medication or supplement, even if prescribed by your doctor, always check with relevant authorities.[3]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

See here too! Asthma

Education

As well as taking medication as prescribed the following suggestions may help some people with EIB manage their symptoms:

- Warming up before exercise

- Being as fit as possible – increasing fitness raises the threshold for EIB, so that moderately strenuous exercise may not cause an attack.

- Exercising in a warm and humid environment

- Avoiding environments with high levels of allergens, pollution, irritant gases or airborne particles.

- Breathing through the nose to help warm and humidify the air

- Using a mask to filter air, although this may be impractical or can make breathing harder

- After strenuous exercise doing cooling down exercise, breathing through the nose and covering the mouth in cold, dry weather

- If client smokes cigarettes, consider speaking to doctor about quitting.

Acute Management:

Because EIB is triggered by exercise, physical therapists may be the first to identify asthma symptoms in a patient with undiagnosed EIB. For this reason, physical therapists must be aware of the associated signs and symptoms of EIB, as well as any red flags that may indicate a need for medical referral and treatment. If a patient has an acute asthma attack during therapy, the physical therapist should assess the severity of the attack, then position the patient in high Fowler’s position for diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breathing, if appropriate. If the patient has an inhaler available, the physical therapist should provide assistance to allow the patient to self-administer the medication, while helping the patient to relax[7].

Long-term Management

There are several factors that can deter patients with EIB from exercising, one being the belief that exercise is detrimental to their condition. Although there is insufficient evidence to support breathing exercises or inspiratory muscle training in patients with asthma, there is strong evidence to support the benefits of physical activity for cardiovascular training in this patient population[7]. Therefore, physical therapists can play a large role in the management of care by providing patient education and exercise prescription. A study protocol will provide the effectiveness of physiotherapy on the quality of life of children with asthma[8].

The Preferred Practice Patterns for this patient population[7], according to the Physical Therapy Guide to Practice[9], include:

- Pattern 6B: Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Deconditioning

- Pattern 6C: Impaired Ventilation, Respiration/Gas Exchange, and Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated With Airway Clearance Dysfunction

- Pattern 6E: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Ventilatory Pump Dysfunction or Failure

- Pattern 6F: Impaired Ventilation and Respiration/Gas Exchange Associated With Respiratory Failure

Exercise and Medication:

Bronchodilators should be self-administered with a meter-dose inhaler (MDI) about 20-30 minutes prior before the patient participates in exercise. Mild stretching and a warm-up to exercise should also be performed during that time to help prevent the onset of asthma symptoms. Physical therapists must be aware of any adverse side effects or drug toxicity associated with asthma medications. Some symptoms that may suggest drug toxicity include nausea and vomiting, tremors, anxiety, tachycardia, arrhythmia, and hypotension. If the patient exhibits asthma symptoms during exercise that are not controlled with current medication, the physical therapist should notify the patient’s physician to alter the dosage[7].

Vital Signs:

It is important for the physical therapist to monitor the patient’s vital signs before, during and after exercise, to detect any abnormal changes in bronchopulmonary function. Auscultation of the lungs should be done routinely to detect any abnormal breath sounds, wheezing, or presence of rhonchi. Red flags that may indicate worsening asthma or drug toxicity can include tachypnea (increased respiratory rate above normative values), diarrhea, headache and vomiting. Asthma-related hypoxemia may be indicated with an abnormal rise in the patient’s blood pressure[7]

Other Considerations:

Decreased bone mass density has been associated with long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe asthma. This chronic corticosteroid use also has an associated increased risk of fracture, in particular asymptomatic vertebral fractures. Physical therapists should be aware of the patient’s medication history and take precautions when exercising patients who may be at risk for fractures. Physical therapy can enhance medical management and play important role in the care of patients with status asthmaticus. Physical therapists can teach the patient various coughing, breathing, and positioning techniques to help clear secretions, reduce hypoxemia and improve V/Q matching. Aggressive treatments, such as forceful percussion, should be avoided in this population to prevent triggering of bronchospasms[7]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Symptoms of chest tightness, wheezing, coughing, and dyspnea occurring with exercise can indicate pathology along the entire airway. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is not easily diagnosed by clinical symptoms, and objective data of a decrease in lung function with exercise is required[1]

The most common differential diagnoses of EIB include[10]:

- Vocal Cord Dysfunction

- Laryngeal/tracheal processes

- Respiratory tract infection

- Gastro-esophageal reflux

- Hyperventilation syndromes

EIB may also be associated with underlying conditions, such as[11]:

- COPD

- Obesity

- Pectus Excavatum

- Diaphragmatic paralysis

- Interstitial Fibrosis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Gerow M, Bruner PJ. Exercise Induced Asthma. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls. 2020.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557554/ (accessed 6.4.2021)

- ↑ The Conversation Winter Olympics: why many athletes will be struggling with asthma Available from:https://theconversation.com/winter-olympics-why-many-athletes-will-be-struggling-with-asthma-90400 (accessed 6.4.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Asthma org. EIB Available from:https://asthma.org.au/about-asthma/triggers/exercise-induced-bronchoconstriction/ (accessed 6.4.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. W B Saunders Company; 2012. 298

- ↑ "Exercise-induced asthma." Mayo Clinic. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/exercise-induced-asthma/basics/definition/con-20033156>.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Section 4, Managing Asthma Long Term—Special Situations. Accessed March 25, 2014 at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. W B Saunders Company; 2012.772-774

- ↑ Zhang W, Liu L, Yang W, Liu H. Effectiveness of physiotherapy on quality of life in children with asthma: Study protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019 Jun;98(26).

- ↑ APTA Guide to Physical Therapist Practice-Online. Cardiovascular/Pulmonary Preferred Practice Patterns. http://guidetoptpractice.apta.org/content/current

- ↑ Schumacher Y, Pottgiesser T, Dickhuth H. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: Asthma in athletes. International Sportmed Journal [serial online]. December 2011;12(4):145-149. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Weiler JM, Anderson SD, Randolph C, et al. Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: a practice parameter. Ann. Allergy. Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(6 Suppl):S1–47. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21167465. Accessed March 25, 2014.