Distal Radial Fractures: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

Evan Thomas (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors'''-[[User:Diane Hodges Popps|Diane Hodges Popps]] | '''Original Editors''' - [[User:Diane Hodges Popps|Diane Hodges Popps]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | |||

== Search | == Search Strategy == | ||

Databases Searched: | Databases Searched: CINAHL, JOSPT, Pubmed, Medline with Full Text, PEDro | ||

The radius is the larger of the two | Keywords Searched: radius, radius anatomy, radius diseases, radius fracture, rehabilitation, wrist joint | ||

<br> | |||

== Definition/Description == | |||

The radius is the larger of the two bones of the forearm, located radially. The end toward the wrist is called the distal end. We can also define the end of the arm as the three centimeters from the radiocarpal joint, where the radius interfaces with the lunate and scaphoid bone of the wrist. A fracture of the distal radius occurs when the area of the radius near the wrist breaks. This can be caused by falling on the outstretched arm in a car, bike or skiing accident and other similar situations. 22 The majority of distal radial fractures are closed injuries in which the overlying skin remains intact.[1][2] ( level of evidence 3A) <br>Distal radius fractures are very common. In fact, the radius is the most commonly broken bone in the arm.<br>For centuries they called this fracture a dislocation of the wrist but this description remains obscure. It was redefined by an Irish surgeon and anatomist, Abraham Colles, in 1814; The name changed to a "Colles' " fracture and that name is to this day continuously used by surgeons. 21 ( level of evidence: 5 )<br><br> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

The wrist joint (also known as the radiocarpal joint) is a synovial joint in the upper lower limb, marking the area of transition between the forearm and the hand. | The wrist joint (also known as the radiocarpal joint) is a synovial joint in the upper lower limb, marking the area of transition between the forearm and the hand. | ||

The wrist joint is formed by:<br>• '''Distally –''' The proximal row of the carpal bones (except the pisiform).<br> os scaphoid<br> os lunate<br> os triquete<br>• P'''roximally''' – The distal end of the radius and the articular disk (see below). | The wrist joint is formed by:<br>• '''Distally –''' The proximal row of the carpal bones (except the pisiform).<br> os scaphoid<br> os lunate<br> os triquete<br>• P'''roximally''' – The distal end of the radius and the articular disk (see below). | ||

A Multiplanar wrist motion is based on three articulations: level of evidence: 5<br>• radioscaphoid<br>• radiolunate<br>• distal radioulnar joints<br> | A Multiplanar wrist motion is based on three articulations: level of evidence: 5<br>• radioscaphoid<br>• radiolunate<br>• distal radioulnar joints<br> | ||

The ulna is not part of the wrist joint – it articulates with the radius, just proximally to the wrist joint, at the distal radio-ulnar joint. Eighty percent of axial load is supported by the distal radius and 20% by the ulna. It is prevented from articulating with the carpal bones by a fibrocartilginous ligament, called the articular disk, which lies over the superior surface of the ulna.<br>Together, the carpal bones form a convex surface, which articulates with the concave surface of the radius and articular disk. All the carpale joints are art sellaris ( the concave part) and the radius the convex part of the joint is seen as an art sphaeroidea.<br>There are several known ligamentous attachments to the distal radius. These often remain intact during distal radius fractures. The volar ligaments are stronger and give more stability to the radiocarpal articulation than the dorsal ligaments do. 23 ( level of evidence 5) <br><br> | |||

The ulna is not part of the wrist joint – it | |||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

Adult distal radial fractures in adults is one of the most common fractures of the upper extremity, accounting for one-sixth of all fractures in the emergency department and can be seen predominantly in the white and older population.<ref name="Handoll 1" /><ref name="Handoll 2" /><ref name="Abramo">Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385</ref><ref name="Bienek">Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.</ref><ref name="Kay">Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.</ref><span style="font-size: 11px;"> | Adult distal radial fractures in adults is one of the most common fractures of the upper extremity, accounting for one-sixth of all fractures in the emergency department and can be seen predominantly in the white and older population.<ref name="Handoll 1" /><ref name="Handoll 2" /><ref name="Abramo">Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385</ref><ref name="Bienek">Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.</ref><ref name="Kay">Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.</ref><span style="font-size: 11px;"> You will almost always have a history of a fall or other kind of trauma. Mostly there is pain and swelling in the forearm or wrist. Presence of deformity in the shape of the wrist is possible if the fracture is bad enough and the presence of bruising (black and blue dislocation) is also possible.41</span> | ||

<span style="font-size: 11px;" />In women, the incidence of occurrence increases with age starting at 40 years old, whereas before this age the incidence in men is much higher. Occurrences in younger adults are usually the result of a high-energy trauma such as a motor vehicle accident. In older adults, such fractures are often the result of a low-energy or moderate trauma such as falling from standing height. This may reflect the greater fragility of the bone due to osteoporosis in the older adult.<ref name="Handoll 1" /><ref name="Leung">Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.</ref> | <span style="font-size: 11px;" />In women, the incidence of occurrence increases with age starting at 40 years old, whereas before this age the incidence in men is much higher. Occurrences in younger adults are usually the result of a high-energy trauma such as a motor vehicle accident. In older adults, such fractures are often the result of a low-energy or moderate trauma such as falling from standing height. This may reflect the greater fragility of the bone due to osteoporosis in the older adult.<ref name="Handoll 1" /><ref name="Leung">Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.</ref> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 45: | ||

2. Classification of extra-articular fracture<br>• Type A: extra-articular<br>• Type A1: extra-articular ulna, radius intact<br>• Type A2: extra-articular radius, ulna intact<br>• Type A3: extra-articular, multi fragmentary radius fracture 25 | 2. Classification of extra-articular fracture<br>• Type A: extra-articular<br>• Type A1: extra-articular ulna, radius intact<br>• Type A2: extra-articular radius, ulna intact<br>• Type A3: extra-articular, multi fragmentary radius fracture 25 | ||

<sup>TYPES OF FRACTURES</sup> | <sup>TYPES OF FRACTURES</sup> | ||

| Line 139: | Line 132: | ||

- ROM of the wrist measuring on both sides with a handheld goniometer.[31]<br>''' Radiographic parameter'''s are used to check the normal anatomy and to detect anatomical anomalies.<br> There are also different disease- specific instruments that are used especially assessing hand- related parameters. For example:<br> Boston carpal tunnel questionnaire<br> Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)<br> The Arthritis Impact measurement scale (AIMS)<br> Australian/Canadian hand osteoarthritis index | - ROM of the wrist measuring on both sides with a handheld goniometer.[31]<br>''' Radiographic parameter'''s are used to check the normal anatomy and to detect anatomical anomalies.<br> There are also different disease- specific instruments that are used especially assessing hand- related parameters. For example:<br> Boston carpal tunnel questionnaire<br> Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)<br> The Arthritis Impact measurement scale (AIMS)<br> Australian/Canadian hand osteoarthritis index | ||

*''' Grip | *''' Grip Strength''' is also an important outcome measure. Because it is an important function in daily activities. The examination is important for the functional recovery of the patient. [38] | ||

Grip strength can be measured with a baseline dynamometer. [31]<br><br> | Grip strength can be measured with a baseline dynamometer. [31]<br><br> | ||

| Line 246: | Line 239: | ||

Due to the fact that distal radial fractures are one of the most common injuries in orthopedics, it is important for physical therapists to understand the risk factors and treatment options. Although further research is needed to ascertain proper post surgical management, it is recommended based on current evidence that patients should be routinely referred to a physical therapist for education and an exercise program. | Due to the fact that distal radial fractures are one of the most common injuries in orthopedics, it is important for physical therapists to understand the risk factors and treatment options. Although further research is needed to ascertain proper post surgical management, it is recommended based on current evidence that patients should be routinely referred to a physical therapist for education and an exercise program. | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

1. ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. External Fixation versus conservative treatment for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>2. ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Different methods of external fixation for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-67.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>3. ↑ Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385<br>level of evidence:2A<br>4. ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.<br>level of evidence: 5 <br>5. ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.<br>level of evidence;3A<br>6. ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.<br>level of evidence:2A<br>7. ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Bushnell BD, Bynum DK. Malunion of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:27-40.<br>level of evidence: 2C<br>8. ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Kleinman WB. Distal radius instability and stiffness; common complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2010;26:245-264.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>9. ↑ Leone J, Bhandari M, Adili A, McKenzie S, Moro JK, Dunlop RB. Predictors of early and late instability following conservative treatment of exta-articular distal radius fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:38-41.<br>level of evidence: 2B<br>10. ↑ 10.0 10.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R. Conservative interventions for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-112.<br>level of evidence: 2C<br>11. ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Patel VP, Paksima N. Complications of distal radius fracture fixation. Bulletin of NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 2010;68(2):112-8.<br>level of evidence: 5<br>12. ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Herzberg G. Intra-articular fracture of the distal radius: arthroscopic-assisted reduction. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:1517-1519.<br>13. ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Handoll HHG, Watts AC. Internal fixation and comparisons of different fixation methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Protocol). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-14.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>14. ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-29.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>15. ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Handoll HHG, Vaghela MV, Madhok R. Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-70.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>16. ↑ 16.0 16.1 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS. Bone grafts and bone substitutes for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2009;3:1-87.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>17. ↑ 17.0 17.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R, Howe TE. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.<br>level of evidence: 2A of 3A<br>18. ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards RS. Pain and disability reported in the year following a distal radius fracture: A cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:24-36.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>19. ↑ Moore CM, Leonardi-Bee J. The prevalence of pain and disability one year post fracture of the distal radius in a UK population: A cross sectional survey. BMC Musculoskeletl Disord. 2008;9:129-138.<br>level of evidence: 2B<br>20. ↑ Brotzman BS, Wilk KE. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby.2007.<br>level of evidence: 5<br>21. Benjamin JA. 1965. Abraham Colles (1773–1843) Distinguished surgeon from Ireland. Invest Urol 3:321–323 <br>level of evidence: 5 <br>22. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00412<br> level of evidence: 5<br>23. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134<br>level of evidence:5<br>24. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134-135<br>level of evidence; 5<br>25. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138<br>level of evidence: 5<br>26. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138<br>level of evidence: 5<br>27. Melone CP Jr., Open treatment for displaced articular fractures of the distal radius, clin Ortop, pg 258-262 <br>level of evidence 1C <br>28. McKay, SD (2001, 26 september). Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/science/article/pii/S0363502301444273# <br>Level of evidence: 2A<br>29. UCONN health. hand and wrist conditions and treatments. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.nemsi.uchc.edu/clinical_services/orthopaedic/handwrist/distal_radius.html<br>Level of evidence: 5<br>30. Jack, A (2013, 25 september). Distal radial fracture imaging. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/398406-overview<br>Level of evidence: 5<br>31. Walenkamp M., et al. “Surgery versus conservative treatment in patients with type A distal radius fractures, a randomised controlled trial.’’ BMC Musculoskeletal disorders 2014, 15:90.<br>http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/90 Level of Evidence, 1B<br>32. Oren T., Wolf J., MD. “Soft- Tissue complications associated with distal radius fractures.” Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics, 19 , 2009, pg. 100—106. <br>Level of Evidence, 2B<br>33. Bot A., Ring D., “Recovery after fracture of the distal radius” Hand Clin 28, (2012) 235-243.<br>Level of Evidence, 3A<br>34. Bruder A., Taylor N., Dodd K., Shields N. “Physiotherapy intervention practice patterns used in rehabilitation after distal radius fracture” Physiotherapy 99 (2013) 233- 240.<br>Level of Evidence, 2B<br>35. P. Cherubino, A. Bini, D. Marcolli. “Management of distal radius fractures: Treatment protocol and functional results” Injury, Int.J. Care injured 41 (2010) 1120- 1126 <br>Level of Evidence, 5<br>36. Michlovitz S., et al. “Distal Radius Fractures: Therapy Practice Patterns” J Hand Ther. 14, (2001): 249-257. <br>Level of Evidence, 2B <br>37. Kay S., McMahon M., Stiller K. “An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture” Australian Journal of Physiotherapy vol.54 (2008) pg. 253- 259.<br>Level of Evidence, 1B<br>38. Leiv M. Hove, Lindau T., Holmer P. “Distal radius fractures: current concepts” Berlin, Heidelberg- Springer (2014) pg. 53- 58 <br>Level of Evidence, 5<br>39. Mitsukane M., et al. “Immediate effects of repetitive wrist extension on grip strength in patients with distal radial fractures” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 12 october 2014.<br>Level of Evidence, 1B<br>40. McKay SD, MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards Rs. “Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist.” J. Hand Surg. Am., nr 5; 26, September 2001: 916-22. Level of Evidence, 2B<br>41. Nelson, DL, ‘wrist fractures’, (2012)<br>http://www.davidlnelson.md/articles/Wrist_Fracture.htm<br>Level of Evidence, 5 | 1. ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. External Fixation versus conservative treatment for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>2. ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Different methods of external fixation for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-67.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>3. ↑ Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385<br>level of evidence:2A<br>4. ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.<br>level of evidence: 5 <br>5. ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.<br>level of evidence;3A<br>6. ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.<br>level of evidence:2A<br>7. ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Bushnell BD, Bynum DK. Malunion of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:27-40.<br>level of evidence: 2C<br>8. ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Kleinman WB. Distal radius instability and stiffness; common complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2010;26:245-264.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>9. ↑ Leone J, Bhandari M, Adili A, McKenzie S, Moro JK, Dunlop RB. Predictors of early and late instability following conservative treatment of exta-articular distal radius fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:38-41.<br>level of evidence: 2B<br>10. ↑ 10.0 10.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R. Conservative interventions for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-112.<br>level of evidence: 2C<br>11. ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Patel VP, Paksima N. Complications of distal radius fracture fixation. Bulletin of NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 2010;68(2):112-8.<br>level of evidence: 5<br>12. ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Herzberg G. Intra-articular fracture of the distal radius: arthroscopic-assisted reduction. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:1517-1519.<br>13. ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Handoll HHG, Watts AC. Internal fixation and comparisons of different fixation methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Protocol). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-14.<br>level of evidence: 3A<br>14. ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-29.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>15. ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Handoll HHG, Vaghela MV, Madhok R. Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-70.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>16. ↑ 16.0 16.1 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS. Bone grafts and bone substitutes for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2009;3:1-87.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>17. ↑ 17.0 17.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R, Howe TE. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.<br>level of evidence: 2A of 3A<br>18. ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards RS. Pain and disability reported in the year following a distal radius fracture: A cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:24-36.<br>level of evidence: 2A<br>19. ↑ Moore CM, Leonardi-Bee J. The prevalence of pain and disability one year post fracture of the distal radius in a UK population: A cross sectional survey. BMC Musculoskeletl Disord. 2008;9:129-138.<br>level of evidence: 2B<br>20. ↑ Brotzman BS, Wilk KE. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby.2007.<br>level of evidence: 5<br>21. Benjamin JA. 1965. Abraham Colles (1773–1843) Distinguished surgeon from Ireland. Invest Urol 3:321–323 <br>level of evidence: 5 <br>22. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00412<br> level of evidence: 5<br>23. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134<br>level of evidence:5<br>24. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134-135<br>level of evidence; 5<br>25. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138<br>level of evidence: 5<br>26. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138<br>level of evidence: 5<br>27. Melone CP Jr., Open treatment for displaced articular fractures of the distal radius, clin Ortop, pg 258-262 <br>level of evidence 1C <br>28. McKay, SD (2001, 26 september). Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/science/article/pii/S0363502301444273# <br>Level of evidence: 2A<br>29. UCONN health. hand and wrist conditions and treatments. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.nemsi.uchc.edu/clinical_services/orthopaedic/handwrist/distal_radius.html<br>Level of evidence: 5<br>30. Jack, A (2013, 25 september). Distal radial fracture imaging. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/398406-overview<br>Level of evidence: 5<br>31. Walenkamp M., et al. “Surgery versus conservative treatment in patients with type A distal radius fractures, a randomised controlled trial.’’ BMC Musculoskeletal disorders 2014, 15:90.<br>http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/90 Level of Evidence, 1B<br>32. Oren T., Wolf J., MD. “Soft- Tissue complications associated with distal radius fractures.” Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics, 19 , 2009, pg. 100—106. <br>Level of Evidence, 2B<br>33. Bot A., Ring D., “Recovery after fracture of the distal radius” Hand Clin 28, (2012) 235-243.<br>Level of Evidence, 3A<br>34. Bruder A., Taylor N., Dodd K., Shields N. “Physiotherapy intervention practice patterns used in rehabilitation after distal radius fracture” Physiotherapy 99 (2013) 233- 240.<br>Level of Evidence, 2B<br>35. P. Cherubino, A. Bini, D. Marcolli. “Management of distal radius fractures: Treatment protocol and functional results” Injury, Int.J. Care injured 41 (2010) 1120- 1126 <br>Level of Evidence, 5<br>36. Michlovitz S., et al. “Distal Radius Fractures: Therapy Practice Patterns” J Hand Ther. 14, (2001): 249-257. <br>Level of Evidence, 2B <br>37. Kay S., McMahon M., Stiller K. “An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture” Australian Journal of Physiotherapy vol.54 (2008) pg. 253- 259.<br>Level of Evidence, 1B<br>38. Leiv M. Hove, Lindau T., Holmer P. “Distal radius fractures: current concepts” Berlin, Heidelberg- Springer (2014) pg. 53- 58 <br>Level of Evidence, 5<br>39. Mitsukane M., et al. “Immediate effects of repetitive wrist extension on grip strength in patients with distal radial fractures” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 12 october 2014.<br>Level of Evidence, 1B<br>40. McKay SD, MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards Rs. “Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist.” J. Hand Surg. Am., nr 5; 26, September 2001: 916-22. Level of Evidence, 2B<br>41. Nelson, DL, ‘wrist fractures’, (2012)<br>http://www.davidlnelson.md/articles/Wrist_Fracture.htm<br>Level of Evidence, 5 | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[Category:Injury]] [[Category:Wrist]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/ | [[Category:Injury]] [[Category:Wrist]] [[Category:Fractures]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Texas_State_University_EBP_Project]] | ||

Revision as of 19:23, 2 October 2017

Original Editors - Diane Hodges Popps

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Diane Hodges Popps, Jocelyn Fu, Kim Jackson, Admin, Katherine Knight, Nupur Smit Shah, Ulrike Lambrix, Jess Bell, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Lauren Lopez, Tony Lowe, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino, Felicia Daigle, Jeremy Brady, Elien Lebuf, Tarina van der Stockt and Karen Wilson

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases Searched: CINAHL, JOSPT, Pubmed, Medline with Full Text, PEDro

Keywords Searched: radius, radius anatomy, radius diseases, radius fracture, rehabilitation, wrist joint

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The radius is the larger of the two bones of the forearm, located radially. The end toward the wrist is called the distal end. We can also define the end of the arm as the three centimeters from the radiocarpal joint, where the radius interfaces with the lunate and scaphoid bone of the wrist. A fracture of the distal radius occurs when the area of the radius near the wrist breaks. This can be caused by falling on the outstretched arm in a car, bike or skiing accident and other similar situations. 22 The majority of distal radial fractures are closed injuries in which the overlying skin remains intact.[1][2] ( level of evidence 3A)

Distal radius fractures are very common. In fact, the radius is the most commonly broken bone in the arm.

For centuries they called this fracture a dislocation of the wrist but this description remains obscure. It was redefined by an Irish surgeon and anatomist, Abraham Colles, in 1814; The name changed to a "Colles' " fracture and that name is to this day continuously used by surgeons. 21 ( level of evidence: 5 )

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The wrist joint (also known as the radiocarpal joint) is a synovial joint in the upper lower limb, marking the area of transition between the forearm and the hand.

The wrist joint is formed by:

• Distally – The proximal row of the carpal bones (except the pisiform).

os scaphoid

os lunate

os triquete

• Proximally – The distal end of the radius and the articular disk (see below).

A Multiplanar wrist motion is based on three articulations: level of evidence: 5

• radioscaphoid

• radiolunate

• distal radioulnar joints

The ulna is not part of the wrist joint – it articulates with the radius, just proximally to the wrist joint, at the distal radio-ulnar joint. Eighty percent of axial load is supported by the distal radius and 20% by the ulna. It is prevented from articulating with the carpal bones by a fibrocartilginous ligament, called the articular disk, which lies over the superior surface of the ulna.

Together, the carpal bones form a convex surface, which articulates with the concave surface of the radius and articular disk. All the carpale joints are art sellaris ( the concave part) and the radius the convex part of the joint is seen as an art sphaeroidea.

There are several known ligamentous attachments to the distal radius. These often remain intact during distal radius fractures. The volar ligaments are stronger and give more stability to the radiocarpal articulation than the dorsal ligaments do. 23 ( level of evidence 5)

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Adult distal radial fractures in adults is one of the most common fractures of the upper extremity, accounting for one-sixth of all fractures in the emergency department and can be seen predominantly in the white and older population.[1][2][3][4][5] You will almost always have a history of a fall or other kind of trauma. Mostly there is pain and swelling in the forearm or wrist. Presence of deformity in the shape of the wrist is possible if the fracture is bad enough and the presence of bruising (black and blue dislocation) is also possible.41

In women, the incidence of occurrence increases with age starting at 40 years old, whereas before this age the incidence in men is much higher. Occurrences in younger adults are usually the result of a high-energy trauma such as a motor vehicle accident. In older adults, such fractures are often the result of a low-energy or moderate trauma such as falling from standing height. This may reflect the greater fragility of the bone due to osteoporosis in the older adult.[1][6]

With women, the incidence of occurrence increases with age starting at 40 years old.

Whereas before this age the incidence in men is opposite and much higher.

Occurrences with younger adults are usually the result of:

• a high-energy trauma

• fall from height

• injuries sustained during athletic participation 24

With older adults the fractures are often the result of a low-energy or moderate trauma such as falling from standing height. This may reflect the greater fragility of the bone due to osteoporosis in the older adult.[1][6]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Distal radial fractures can be classified based on their clinical appearance and typical deformity. Dorsal displacement, dorsal angulation, dorsal comminution, and radial shortening may all be used to describe the presentation of the fracture. Classification based on fracture patterns such as intra-articular (articular surfaces disrupted) or extra-articular (articular surface of radius intact) may also be used.[1][7]

1. Classification of intra-articular fracture

• Type Ι: stable, without communition

• Type ΙΙ: unstable die-punch, dorsal of volar

ΙΙa: reducible

ΙΙb: irreducible

• Type ΙΙΙ: spike fracture; contuses volar structures

• Type ΙV: split fracture : medial complex fractured with dorsal and pamlar fragments displaced seperately

• Type V: explosion fracture; severe communication with major soft-tissue injury

2. Classification of extra-articular fracture

• Type A: extra-articular

• Type A1: extra-articular ulna, radius intact

• Type A2: extra-articular radius, ulna intact

• Type A3: extra-articular, multi fragmentary radius fracture 25

TYPES OF FRACTURES

Colles fracture

This is typically due to a fall on an outstretched hand and results in a dorsal extra-articular or intra-articular displacement of the fractured radius:

• Intra-articular fractures are generally seen in the younger age group secondary to higher energy forces

• More than 90% of distal radius fractures are of this pattern 25

www.physio-pedia.com/Colles_Fracture

“Smith’s” fracture

This is a reverse Colles with a volar displacement and a fall on a flexed wrist with forearm fixed in supination. 25

“Barton’s” fracture

This is an intra-articular fracture with subluxation or dislocation of the carpus bone. Of the 8 grades for distal radial fractures in the Frykman classification system, half include ulnar syloid involvement.

Complications are common and diverse. They may be the result of injury or treatment and are associated with poorer outcomes. These can include:32

• upper extremity stiffness

• carpal tunnel syndrome or median nerve involvement

• malunion

• carpal instability

• DRUJ dysfunction

• Dupuytren’s disease

• radiocarpal arthritis

• tendon/ligament injuries

• post traumatic osteoarthritis

• compartment syndrome

• infection mostly by open fractures 25,32

• complex regional pain syndrome.[4][8][10][11]

www.physio-pedia.com/Complex_Regional_Pain_Syndrome

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Because the mechanism of injury for a distal radial fracture is usually a high energy traumatic incident, radiographs should be taken to confirm the diagnosis and ensure that the surrounding tissues are still intact. Other injuries causing radial sided pain may include TFCC wear or preforation, Galeazzi fracture (fracture to the distal 2/3 of the radius), scaphoid fracture, or radiocarpal ligament injury.

- 'Malun'ion--Distal radius malunion is the most common complication, affecting up to 17% of patients. Physical therapists may assess the effect of malunion to determine if surgery is appropriate by performing a detailed physical exam that includes a preoperative history, location and severity of pain, and functional loss.[7][11]

- Compartment Syndrome - Incidence of this complication affects only 1% of patients. Elevate, observe, and loosen cast immediately if compartment syndrome is suspected.[11]

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) - This complication is observed in 8-35% of patients.[11] CRPS should be suspected when pain, decreased ROM, skin temperature, color, and swelling are out of proportion to the injury. In order to obtain a good functional outcome for this patient population, early recognition and a multidisciplinary treatment approach to address pain and function requires psychiatric and physical/occupational therapy interventions.

- Dupeytren’s Disease - Patients develop mild contractures in the palm along the fourth and fifth rays within six months of a distal radial fracture. The severity of the contractures determines the treatment course.[11]

Nerve Pathology – Neuropathy may present acutely or throughout treatment. The median nerve is most common (4%), however 1% of patients have ulnar or radial involvement.[4] Physiotherapists may need to refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon.[11]

- Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome – Physiotherapists must be able to identify acute carpal tunnel syndrome, as delayed treatment is associated with poor outcomes, incomplete recovery, or a prolonged functional recovery time.[4][11]

- Tendon Complications - Physiotherapists should be prepared to refer patients to surgery in the event of tendon complications secondary to irritation with inflammation or rupture from impingement.[11]

Capsule Contracture - Even after physical therapy treatment, some patients do not regain full forearm rotation due to contracture of the distal radioulnar joint capsule. Dorsal contracture limits pronation, volar contracture limits supination, and both may occur together. A DRUJ capsulectomy may be considered if functional ROM is not regained.[8]

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

There are many classification systems that describe fractures of the distal radius. Classification systems should follow the following 2 principles:

- The classification should prescribe the treatment.

- The classification should suggest the long-term, functional results of treatment or be correlated with these anticipated results. 25

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

A Distal Radius Fracture Complication Checklist and Score Sheet was developed to improve prospective data collection. The checklist includes:

- a classification for all DRF complications

- allows for assessment of severity of each complication.

- A score must be given to each part of the questionnaire : Mild = 1, Moderate = 2, Severe = 3

- The categories of the questionnaire are :

nerve complications, bone/joint complications, tendon complications

with at the end the total number of complications

and the total score (sum of all complication scores) [40] level of evidence 2B

- The Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH) [31][38]

It is a validated outcome measure of the upper extremity.

www.physio-pedia.com/DASH_Outcome_Measure

- The Gartland and Werley Score is an objective measurement to predict overall recovery.

- The Patient- Rated wrist evaluation (PRWE) * [31] [38]

[[|]]www.physio-pedia.com/PRWE_Score

- The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ)*

It is a hand-specific outcomes instrument devided in six scales: (1) overall hand function, (2) activities of daily living, (3) pain, (4) work performance, (5) aesthetics, and (6) patient satisfaction with hand function

These 2 questionnaires are the most frequently used to assess distal radial fracture outcomes. Because they are more specific to wrist function.

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), to indicate pain. [31]

0 implies no pain and 10 the worst possible pain.

- Physical Examination is also an important outcome measure. (Being aware that controlling with the contralateral extremity may be an unreliable control.) [38]

- ROM of the wrist measuring on both sides with a handheld goniometer.[31]

Radiographic parameters are used to check the normal anatomy and to detect anatomical anomalies.

There are also different disease- specific instruments that are used especially assessing hand- related parameters. For example:

Boston carpal tunnel questionnaire

Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)

The Arthritis Impact measurement scale (AIMS)

Australian/Canadian hand osteoarthritis index

- Grip Strength is also an important outcome measure. Because it is an important function in daily activities. The examination is important for the functional recovery of the patient. [38]

Grip strength can be measured with a baseline dynamometer. [31]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical therapists must conduct a thorough physical exam including subjective and objective information.

- Subjective exam includes any information given by the patient about pain experienced, limitations of ROM of the wrist, and activity limitations.[4]

- Objective exam includes assessment of wrist and digit ROM, grip and forearm strength, bony and soft-tissue abnormalities, skin integrity, and nerve involvement.[4]

Health care professionals should always evaluate the ligamentous integrity in the presence of carpal instability and persistent pain as early as possible in order to avoid poor functional outcomes and prolonged recovery. Specific fracture patterns and high energy injuries are strongly indicative of intercarpal ligament involvement.[8]

To confirm the diagnosis, the doctor will ask for an x-ray. X-rays are the most common and broadly available diagnostic imaging technique. They can show if a bone is broken and whether there is displacement (gap between broken bones). In addition, they can also show how many pieces of broken bone there are. 22 Level of evidence: 5

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Orthopedic surgeons typically recommend surgical repair of displaced articular fractures of the distal radius for active, healthy people.[9] The sheer variety of reduction and fixation options is noted based on a series of five Cochrane reviews focusing on this topic alone. Methods include: closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, either extra-focal or intra-focal; bridging external fixation with or without supplemental Kirschner-wire fixation; dorsal plating; fragment-specific fixation; open reduction and internal fixation with a volar plate through a classic Henry approach; or a combination of these methods.[1][2][7][9][10][11][12] Surgical “complications include edema, hematoma, stiffness, infection, neurovascular injury, loss of fixation, recurrent malunion, nonunion or delayed union, instability, tendon irritation or ruptures, osteoarthritis, residual ulnar-side pain, median neuropathy, complex regional pain syndrome, and problems with the bone-graft harvest site."[7]

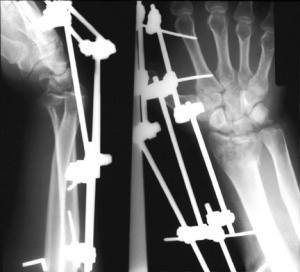

- External Fixation – External fixation is typically a closed, minimally invasive method in which metal pins or screws are driven into the bone via small incisions in the skin. These pins can then be fixed externally by either a plaster cast or securing them into an external fixator frame.[1][2] In comparison to a standard immobilization procedure, external fixation of distal radius fractures reduces redisplacement and yields better anatomical results. However, current evidence for better functional outcomes from external fixation is weak and is also associated with high risk for complications such as pin site infections and radial nerve injuries. A radiographic example is shown in Figure 2.

- Internal fixation – Internal fixation involves open surgery where the fractured bone is exposed. Dorsal, volar or T-plates with screws may be used.[7] However, due to the invasive and demanding nature of open surgery, there is an increased risk of infection and soft-tissue damage and therefore this type of fixation is usually reserved for more severe injuries.[10] Figure 3 is a radiographic image of internal fixation. level of evidence: 3A

- Bone Grafts - Upon reduction of distal radial fractures, bony voids are common and can be reduced by inserting bone grafts or bone graft substitutes. Autogenous bone material obtained from the patient themselves or allogenous bone material obtained from cadaver or live donors can be used as filler for reducing bony voids. However, current research describes risk of complications including infection, nerve injury, or donor site pain, and limited evidence that bone scaffolding may improve anatomical or functional outcomes.[13] Bone grafting is required by most procedures except closing wedge.[7] level of evidence: 3A

- Percutaneous Pinning - Another strategy in reducing and stabilizing the fractures is percutaneous pinning, which involves insertion of pins, threads or wires through the skin and into the bone.[12][7] This procedure is typically less invasive and reduction of the fracture is closed upon which the pins placed in the bone are used to fix the distal radial fragment. Current indications for the best technique of pinning, the extent and duration of immobilization are uncertain, in which the excess of complications are likely to outweigh therapeutic benefits of pinning. Figure 4 is a radiograph of pinning. level of evidence: 2C

- Closed Reduction - In closed reduction, displaced radial fragments are repositioned using different maneuvers while the arm is in traction. Different methods include manual reduction in which two people pull in the opposite directions to produce and maintain longitudinal traction and mechanical methods of reduction including the use of “finger traps.” However there is insufficient evidence establishing the effectiveness of different methods of closed reduction used in treating distal radial fractures.[11]

- Arthroscopic-assisted reduction has many advantages over open reduction. In addition to being less invasive, arthroscopic-assisted reduction allows for direct visualization and reduction of articular displacement, opportunity to diagnose and treat associated ligamentous injuries, removal of articular cartilage debris, and lavage of radiocarpal joint. The primary limitations for arthroscopic reduction are due the limited number of surgeons with experience, a longer, more difficult procedure, and the potential for compartment syndrome or acute carpal tunnel syndrome with fluid extravasation.[9]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Current physical therapy management for distal radius fractures covers post-surgical or post-immobilization treatment.[5] The treatment of distal radius fractures is controversial and further research is required. There is a great need of versatility in the treatment options and there is no gold standard of treatment. The best treatment option must be decided in accordance to the type of fracture evaluated from the radiographs after temporary reduction.

Two third of all dorsal radius fractures are relocated and are especially extra articular. Surgical treatment is used when the fracture re- displacement occurs. It contains surgical reduction and fixation with a volar locking plate or in the other case ( people with displaced extra- articular DRF’s)

We list the possible treatments on.

Treatment

There is one basic rule with broken bones, broken pieces must be prevented from moving out of place. There are several treatment positions for distal radial fracture, the choice depends on:

- Nature of fracture

- Age

- Activity level

- And the surgeon’s personal preferences [22] level of evidence: 5

Non-surgical Treatment

When the broken bone is in a good position you can apply a plaster until the bone heals.

If the bone is not in a good position, then it may be necessary to realign the broken bone fragments. The doctor will remove the broken pieces into their original place. This action or act is called the 'reduction’. But when a bone is straightened without making an incision to open the skin, they call it a closed reduction.

After the bone is aligned, a splint or cast may be placed and will be removed about 6 weeks after the fracture happened (they change the cast after 2 a 3 weeks when the swelling goes down otherwise it will be to big). After this, physical therapy will be started to improve the function of the injured wrist. [22] level of evidence: 5

Surgical Treatment

Now and then the position of the bone is so much out of place that surgery may be required.

Procedure: they making an incision to directly access the broken bones to improve alignment (open reduction).

Depending on the fracture, there are several of options for holding the bone in the correct position while it heals:

- Cast

- Metal pins (usually stainless steel or titanium)

- Plate and screws

- External fixator (a a stabilizing frame outside the body that holds the bones in the proper position so they can heal) [22] level of evidence: 5

Recovery

Because the kinds of distal radius fractures are so varied and the treatment options are so broad, recovery is different for each individual. Talk to your doctor for specific information about your recovery program and return to daily activities. [22] level of

Pain Management

Most fractures hurt for a few days to a couple of weeks. Many patients find that using ice, elevation and simple, non-prescription medications for pain relief are all that are needed to relieve pain.

[22] level of evidence: 5

Rehabilitation

We have compared several treatments with each other and found different grades of effectiveness.

- During immobilization:

ROM exercises> compressive wrap> dexterity exercises> resting splints > soft tissue mobilization > joint mobilization > dynamic splints

- Preferred modalities during immobilization:

Heat/cold modalities> ; at less than 10% of the treatments ;

ultrasound > electrical stimulation> CPM (continuous passive motion) > EMG/ biofeedback

- After immobilization:

ROM exercises > compressive wrap/ dexterity exercises/ joint mobilization> soft tissue mobilization > dynamic splints > resting splints

- Preferred modalities after immobilization:

Heat/ cold modalities > ultrasound > electrical stimulation/ CPM > EMG/biofeedback

[36] level of evidence 2B `

It has been proven that an advice- and exercise program provides some additional benefits over no intervention for adults following a distal radius fracture. Especially pain and activity limitations had better outcome measures. [37] level of evidence 1B

The Functional outcome following is as follows : closed reduction and plaster immobilization [31] level of evidence 1B

Advice

Use of self- management approach developing positive health behaviors during rehabilitation.

Self- Management programs can provide benefits in participants’ knowledge, symptom management, self- management behavioursbehaviors, self- efficacy and aspects of health status.

These programs are usually given to patients with chronic illnesses. [34] level of evidence 2B

This table below shows some details of a recommended physical therapy treatment for the first twelve weeks following fracture reduction. [20] level of evidence: 5

During the first two months, patients report severe pain during movement and severe disability during activities of daily living as assessed with valid and reliable outcome measures such as the Patient Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE) and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH).[18] These deficits are reflected in decreased range of motion and decreased grip strength measurements with strength being more highly correlated with functional ability. However, most patients achieve the majority of recovery within the first six months. A small minority of patients will experience persistent pain and disability at one year post injury regardless of treatment protocol,[4][18][19] especially when pushing up from sit to stand and carrying weight. Patients expressing atypical recovery from distal radial fractures need modified treatment programs with goals toward increasing workability.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Handoll et al conducted eight Cochrane Reviews targeting distal radial fractures. There was insufficient data from which to draw conclusions. This may be due to poor study design and the heterogeneity of distal radial fractures themselves.

• Different methods of external fixation for treating distal radial fractures in adults[2]

• External Fixation versus conservative treatment for distal radial fractures in adults[1]

• Internal fixation and comparisons of different fixation methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults[10]

• Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults[11]

• Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults[12]

• Bone grafts and bone substitutes for treating distal radial fractures in adults[13]

• Conservative interventions for treating distal radial fractures in adults[14]

• Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults[15]

A 2008 randomized control trial, Kay et al[5] was supportive of physical therapy intervention, though limitations in the study abound. While no significant differences in grip strength and wrist extension were found in the experimental group, it is important to note that some of the secondary measures showed significant improvement as compared to the control group. These include benefits in activity, pain, and satisfaction.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Due to the fact that distal radial fractures are one of the most common injuries in orthopedics, it is important for physical therapists to understand the risk factors and treatment options. Although further research is needed to ascertain proper post surgical management, it is recommended based on current evidence that patients should be routinely referred to a physical therapist for education and an exercise program.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHandoll 1 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHandoll 2 - ↑ Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.

- ↑ Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBushnell - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPatel - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Herzberg G. Intra-articular fracture of the distal radius: arthroscopic-assisted reduction. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:1517-1519.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Handoll HHG, Watts AC. Internal fixation and comparisons of different fixation methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Protocol). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-14.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-29.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Handoll HHG, Vaghela MV, Madhok R. Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-70.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS. Bone grafts and bone substitutes for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2009;3:1-87.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHandoll 3 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHandoll 8

1. ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. External Fixation versus conservative treatment for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.

level of evidence: 3A

2. ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Different methods of external fixation for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-67.

level of evidence: 3A

3. ↑ Abramo A, Kopylov P, Tagil M. Evaluation of a treatment protocol in distal radius fractures: a prospective study in 581 patients using DASH as outcome. Acta Orthopaedica. 2008;79(3):376-385

level of evidence:2A

4. ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Bienek T, Kusz D, Cielinski L. Peripheral nerve compression neuropathy after fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. (British and European Volume). 2006;31B(3):256-260.

level of evidence: 5

5. ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kay S, McMahon M, Stiller K. An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:253-259.

level of evidence;3A

6. ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leung F, Ozkan M, Chow SP. Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius – factors affecting functional outcomes. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):145-153.

level of evidence:2A

7. ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Bushnell BD, Bynum DK. Malunion of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:27-40.

level of evidence: 2C

8. ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Kleinman WB. Distal radius instability and stiffness; common complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2010;26:245-264.

level of evidence: 3A

9. ↑ Leone J, Bhandari M, Adili A, McKenzie S, Moro JK, Dunlop RB. Predictors of early and late instability following conservative treatment of exta-articular distal radius fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:38-41.

level of evidence: 2B

10. ↑ 10.0 10.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R. Conservative interventions for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-112.

level of evidence: 2C

11. ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Patel VP, Paksima N. Complications of distal radius fracture fixation. Bulletin of NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 2010;68(2):112-8.

level of evidence: 5

12. ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Herzberg G. Intra-articular fracture of the distal radius: arthroscopic-assisted reduction. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:1517-1519.

13. ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Handoll HHG, Watts AC. Internal fixation and comparisons of different fixation methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Protocol). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-14.

level of evidence: 3A

14. ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-29.

level of evidence: 2A

15. ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Handoll HHG, Vaghela MV, Madhok R. Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-70.

level of evidence: 2A

16. ↑ 16.0 16.1 Handoll HHG, Huntley JS. Bone grafts and bone substitutes for treating distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2009;3:1-87.

level of evidence: 2A

17. ↑ 17.0 17.1 Handoll HHG, Madhok R, Howe TE. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2008;4:1-78.

level of evidence: 2A of 3A

18. ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards RS. Pain and disability reported in the year following a distal radius fracture: A cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:24-36.

level of evidence: 2A

19. ↑ Moore CM, Leonardi-Bee J. The prevalence of pain and disability one year post fracture of the distal radius in a UK population: A cross sectional survey. BMC Musculoskeletl Disord. 2008;9:129-138.

level of evidence: 2B

20. ↑ Brotzman BS, Wilk KE. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby.2007.

level of evidence: 5

21. Benjamin JA. 1965. Abraham Colles (1773–1843) Distinguished surgeon from Ireland. Invest Urol 3:321–323

level of evidence: 5

22. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00412

level of evidence: 5

23. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134

level of evidence:5

24. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 134-135

level of evidence; 5

25. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138

level of evidence: 5

26. Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman, Handbook of fractures, Philadelphia, second edition, 1994, pg 135-138

level of evidence: 5

27. Melone CP Jr., Open treatment for displaced articular fractures of the distal radius, clin Ortop, pg 258-262

level of evidence 1C

28. McKay, SD (2001, 26 september). Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/science/article/pii/S0363502301444273#

Level of evidence: 2A

29. UCONN health. hand and wrist conditions and treatments. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://www.nemsi.uchc.edu/clinical_services/orthopaedic/handwrist/distal_radius.html

Level of evidence: 5

30. Jack, A (2013, 25 september). Distal radial fracture imaging. Geraadpleegd op: 17/04/2015 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/398406-overview

Level of evidence: 5

31. Walenkamp M., et al. “Surgery versus conservative treatment in patients with type A distal radius fractures, a randomised controlled trial.’’ BMC Musculoskeletal disorders 2014, 15:90.

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/90 Level of Evidence, 1B

32. Oren T., Wolf J., MD. “Soft- Tissue complications associated with distal radius fractures.” Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics, 19 , 2009, pg. 100—106.

Level of Evidence, 2B

33. Bot A., Ring D., “Recovery after fracture of the distal radius” Hand Clin 28, (2012) 235-243.

Level of Evidence, 3A

34. Bruder A., Taylor N., Dodd K., Shields N. “Physiotherapy intervention practice patterns used in rehabilitation after distal radius fracture” Physiotherapy 99 (2013) 233- 240.

Level of Evidence, 2B

35. P. Cherubino, A. Bini, D. Marcolli. “Management of distal radius fractures: Treatment protocol and functional results” Injury, Int.J. Care injured 41 (2010) 1120- 1126

Level of Evidence, 5

36. Michlovitz S., et al. “Distal Radius Fractures: Therapy Practice Patterns” J Hand Ther. 14, (2001): 249-257.

Level of Evidence, 2B

37. Kay S., McMahon M., Stiller K. “An advice and exercise program has some benefits over natural recovery after distal radius fracture” Australian Journal of Physiotherapy vol.54 (2008) pg. 253- 259.

Level of Evidence, 1B

38. Leiv M. Hove, Lindau T., Holmer P. “Distal radius fractures: current concepts” Berlin, Heidelberg- Springer (2014) pg. 53- 58

Level of Evidence, 5

39. Mitsukane M., et al. “Immediate effects of repetitive wrist extension on grip strength in patients with distal radial fractures” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 12 october 2014.

Level of Evidence, 1B

40. McKay SD, MacDermid JC, Roth JH, Richards Rs. “Assessment of complications of distal radius fractures and development of a complication checklist.” J. Hand Surg. Am., nr 5; 26, September 2001: 916-22. Level of Evidence, 2B

41. Nelson, DL, ‘wrist fractures’, (2012)

http://www.davidlnelson.md/articles/Wrist_Fracture.htm

Level of Evidence, 5