Disc Herniation

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (25/01/2020)

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common low back disorder. It is one of the most common diseases that produces low back pain and/or leg pain in adults[1]., A herniated disc is a displacement of disc material (nucleus pulposus or annulus fibrosis) beyond the intervertebral disc space[2]. This herniation process begins from failure in the innermost annulus rings and progresses radially outward. The damage to the annulus of the disc appears to be associated with fully flexing the spine for a repeated or prolonged period of time. The nucleus loses its hydrostatic pressure and the annulus bulges outward during disc compression[3]. Other names used to describe this type of pathology are: prolapsed disc, herniated nucleus pulposus and discus protrusion[4][5][6].

- The management of disc herniation requires an interprofessional team. The initial treatment should be conservative, unless a patient has severe neurological compromise.

- Surgery is usually the last resort as it does not always result in predictable results. Patients are often left with residual pain and neurological deficits, which are often worse after surgery.

- Physical therapy is the key for most patients. The outcomes depend on many factors but those who particpate in regular exercise and maintain a healthy body weight have better outcomes than people who are sedentary[7].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

see Lumbar Anatomy for great detail

Intervertebral discs

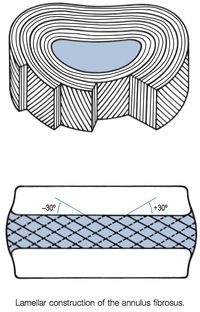

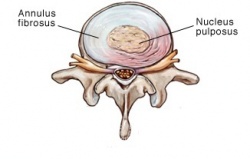

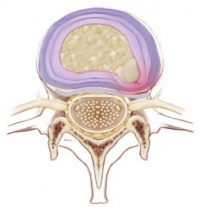

Two adjacent vertebral bodies are linked by an intervertebral disc. Together with the corresponding facet joints, they form the ‘functional unit of Junghans’n The disc consists of an annulus fibrosus, a nucleus pulposus and two cartilaginous endplates. The distinction between annulus and nucleus can only be made in youth, because the consistency of the disc becomes more uniform in the elderly. For this reason, nuclear disc protrusions are rare after the age of 70. From a clinical point of view, it is important to consider the disc as one integrated unit, the normal function of which depends largely on the integrity of all the elements. That means that damage to one component will create adverse reactions in the others[8].

The disc contain an

- Endplate

- Annulus fibrosus

- Nucleus pulposus

Etiology[edit | edit source]

An intervertebral disc is composed of annulus fibrous which is a dense collagenous ring encircling the nucleus pulposus.

- Disc herniation occurs when part or all the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the annulus fibrous.

- The most common cause of disc herniation is a degenerative process in which as humans age, the nucleus pulposus becomes less hydrated and weakens. This process will lead to progressive disc herniation that can cause symptoms.

- The second most common cause of disc herniation is trauma.

- Other causes include connective tissue disorders and congenital disorders such as short pedicles.

- Disc herniation is most common in the lumbar spine followed by the cervical spine. A high rate of disc herniation in the lumbar and cervical spine can be explained by an understanding of the biomechanical forces in the flexible part of the spine. The thoracic spine has a lower rate of disc herniation[7].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of herniated discs is believed to be a combination of the mechanical compression of the nerve by the bulging nucleus pulposus and the local increase in inflammatory chemokines.[7]

The disc consists of the annulus fibrosus (a complex series of fibrous rings) and the nucleus pulposus (a gelatinous core containing collagen fibers, elastin fibers and a hydrated gel)[9]. The vertebral canal is formed by the vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs and ligaments on the anterior wall and by the vertebral arches and ligaments on the lateral wall. The spinal cord lies in this vertebral canal[10].

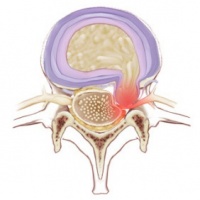

A tear can occur within the annulus fibrosus. The material of the nucleus pulposus can track through this tear and into the intervertebral or vertebral foramen to impinge neural structure[10]. A disc herniation can cause mechanical irritation of these structures which in turn can cause pain. This is presented as low back pain with possible radiculopathy if a nerve is affected[11]. The disc can protrude posteriorly and impinge the roots of the lumbar nerves or it can protrude posterolaterally and impinge the descending root[10].

A disc has few blood vessels and some nerves. These nerves are mainly restricted to the outer lamellae of the annulus fibrosus. In the lumbar region, the level at which a disc herniates does not always correlate to the level of nerve root symptoms[9]. When the herniation is in the posterolateral direction the affected nerve root is the one that exits at the level below the disk herniation. This is because the nerve root at the hernia-level has already exited the transverse foramen. A foraminal herniation on the other hand affects the nerve root that is situated at the same level.

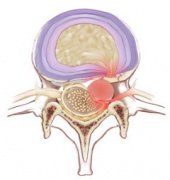

There are four types of herniated discs described in Clinical Anatomy and Management of Back Pain (2006)[12]:

1. Bulging:extension of the disc margin beyond the margins of the adjacent vertebral endplates

2. Protrusion:the posterior longitudinal ligament remains intact but the nucleus pulposus impinges on the anulus fibrosus

3. Extrusion:the nuclear material emerges through the annular fibers but the posterior longitudinal ligament remains intact

4. Sequestration:the nuclear material emerges through the annular fibers and the posterior longitudinal ligament is disrupted. A portion of the nucleus pulposus has protruded into the epidural space

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of herniated disc is about 5 to 20 cases per 1000 adults annually and is most common in people in their third to the fifth decade of life, with a male to female ratio of 2:1.

In 95% of the lumbar disc herniation the L4-L5 and L5-S1 discs are affected[13].

Lumbar disc herniation occurs 15 times more than cervical disc herniation, and is an important cause of lower back pain[14][15].

The prevalence of a symptomatic herniated lumbar disc is about 1% to 3% with the highest prevalence among people aged 30 to 50 years, with a male to female ratio of 2:1.

In individuals aged 25 to 55 years, about 95% of herniated discs occur at the lower lumbar spine (L4/5 and L5/S1 level); disc herniation above this level is more common in people aged over 55 years[16].

Recurrent lumbar disc herniation (rLDH) is a common complication following primary discectomy.

The cervical disc herniation is most affected 8% of the time and most often at level C5-C6 and C6-C7.

History and Examination[edit | edit source]

Cervical Spine

History

In the cervical spine, the C6-7 is the most common herniation disc that causes symptoms, mostly radiculopathy. History in these patients should include the chief complaint, the onset of symptoms, where the pain starts and radiates. History should include if there are any past treatments.

Physical examination

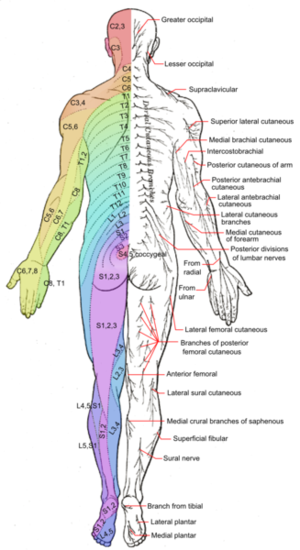

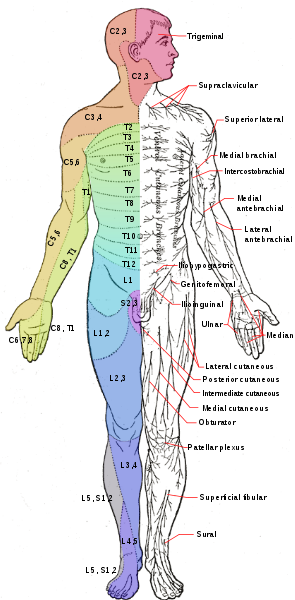

On physical examination, particular attention should be given to weaknesses and sensory disturbances, and their myotome and dermatomal distribution.

Typical findings of solitary nerve lesion due to compression by herniated disc in cervical spine

- C5 Nerve - neck, shoulder, and scapula pain, lateral arm numbness, and weakness during shoulder abduction, external rotation, elbow flexion, and forearm supination. The reflexes affected are the biceps and brachioradialis.

- C6 Nerve - neck, shoulder, scapula, and lateral arm, forearm, and hand pain, along with lateral forearm, thumb, and index finger numbness. Weakness during shoulder abduction, external rotation, elbow flexion, and forearm supination and pronation is common. The reflexes affected are the biceps and brachioradialis.

- C7 Nerve - neck, shoulder, middle finger pain are common, along with the index, middle finger, and palm numbness. Weakness on the elbow and wrist are common, along with weakness during radial extension, forearm pronation, and wrist flexion may occur. The reflex affected is the triceps.

- C8 Nerve - neck, shoulder, and medial forearm pain, with numbness on the medial forearm and medial hand. Weakness is common during finger extension, wrist (ulnar) extension, distal finger flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction, along with during distal thumb flexion. No reflexes are affected.

- T1 Nerve - pain is common in the neck, medial arm, and forearm, whereas numbness is common on the anterior arm and medial forearm. Weakness can occur during thumb abduction, distal thumb flexion, and finger abduction and adduction. No reflexes are affected.[7]

Lumbar Spine

History

In the lumbar spine, herniated disc can present with symptoms including sensory and motor abnormalities limited to specific myotome. History in these patients should include chief complaints, the onset of symptoms, where the pain starts and radiates. History should include if there are any past treatments.

Physical Examination

A careful neurological examination can help in localizing the level of the compression. The sensory loss, weakness, pain location and reflex loss associated with the different level are described below

Typical findings of solitary nerve lesion due to compression by herniated disc in lumbar spine

- L1 Nerve - pain and sensory loss are common in the inguinal region. Hip flexion weakness is rare, and no stretch reflex is affected.

- L2-L3-L4 Nerves - back pain radiating into the anterior thigh and medial lower leg; sensory loss to the anterior thigh and sometimes medial lower leg; hip flexion and adduction weakness, knee extension weakness; decreased patellar reflex.

- L5 Nerve - back, radiating into buttock, lateral thigh, lateral calf and dorsum foot, great toe; sensory loss on the lateral calf, dorsum of the foot, web space between first and second toe; weakness on hip abduction, knee flexion, foot dorsiflexion, toe extension and flexion, foot inversion and eversion; decreased semitendinosus/semimembranosus reflex.

- S1 Nerve - back, radiating into buttock, lateral or posterior thigh, posterior calf, lateral or plantar foot; sensory loss on posterior calf, lateral or plantar aspect of foot; weakness on hip extension, knee flexion, plantar flexion of the foot; Achilles tendon; Medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; weakness may be minimal, with urinary and fecal incontinence as well as sexual dysfunction.

- S2-S4 Nerves - sacral or buttock pain radiating into the posterior aspect of the leg or the perineum; sensory deficit on the medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; absent bulbocavernosus, anal wink reflex[7].

Neurological Examination[edit | edit source]

- The straight leg raise test: With the patient lying supine, the examiner slowly elevates the patient’s led at increasing angle, while keeping the leg straight at the knee joint. The test is positive if it reproduces the patient’s typical pain and paresthesia.

- The contralateral (crossed) straight leg raise test: As in the straight leg raise test, the patient is lying supine, and the examiner elevates the asymptomatic leg. The test is positive if the maneuver reproduces the patient's typical pain and paresthesia. The test has a specificity greater than 90%.[7]

- Lasègue’s Test Crossed Lasegue test (XSLR) This test is considered to be positive when the pain (sciatica) can be reproduced upon passive extension of the contra-lateral leg.

- Slump Test The sitting patient (with convex back) bends his head forward and stretches his leg out with the toes pointing upward. The purpose is to stretch the neural structures within the vertebral canal and foramen[1].

- Scoliosis The therapist is going to evaluate this parameter using visual inspection. Scoliosis might be a potential indicator of lumbar disc herniation. Research has proven that the diagnostic performance of this test is really poor. The sensitivity and specificity are really low[1].

- Muscle Weakness or Paresis The examiner measures strength during ankle dorsiflexion or extension of the big toe (without or against resistance). Dorsal flexion impaired --> L4 radiculopathyToe extension impaired --> L5 radiculopathyIf the possible range at the symptomatic side differs from the non-symptomatic side, then the test is considered to be positive[1].

- Reflexes Weakness or absence of the Achilles tendon reflex possibly refers to S1 radiculopathy[1]

- Forward Flexion Test The purpose is to bend forward in standing position. There is no consensus regarding the criteria that have to be considered in order to determine if the radiant pain is caused by disc herniation. Some studies use limitation of forward flexion as main criteria, while others use back/leg pain as the primary indicator.[1]

- Hyperextension Test The patient needs to passively mobilise the trunk over the full range of extension, while the knees stay extended. The test indicates that the radiant pain is caused by disc herniation if the pain deteriorates.[1]

- Manual Testing and Sensory Testing Look for hypoaesthesia, hypoalgesia, tingling or numbness[1]. One example of testing: the patient closes his eyes and the examiner strikes the skin bilaterally and simultaneously. The patient is asked if he feels any differences between the left and right side. The test is considered to be positive when there is a dermatomal distribution. Although, the diagnostic performance of sensitivity and specificity is poor.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are different pathologies that can imitate a herniated disc from the clinical and the imaging point of view, that should be considered .

These lesions include those originating from the

- vertebral body (osteophytes and metastases),

- intervertebral disc (discal cyst),

- intervertebral foramina (neurinomas)

- interapophyseal joints (synovial cyst)

- epidural space (hematoma and epidural abscess).[17]

Other differential diagnoses include

- Mechanical pain

- Myofascial pain[18] (leads to local and/or referred pain, sensory disturbances)

- Spondylosis/spondylolisthesis

- Spinal/ lumbar stenosis[18] (leads to mild low back pain, multiradicular pain in one or both legs, mild motor deficits)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

X-rays: These are very accessible at most clinics and outpatient offices. This imaging technique can be used to assess for any structural instability. If x-rays show an acute fracture, it needs to be further investigated using CT scan or MRI.

CT Scan: It is preferred study to visualize bony structures in the spine. It can also show calcified herniated discs. It is less accessible in the office settings compared to x-rays. But, it is more accessible than MRI. In the patients that have non-MRI comparable implanted devices, CT myelography can be performed to visualize herniated disc.

MRI: It is the preferred and most sensitive study to visualize herniated disc. MRI findings will help surgeons and other providers plan procedural care if it is indicated.[7]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

If the disc herniation is symptomatic different outcome measures can be used:

- Short Form-36 bodily pain (SF-36 BP)

- Physical function scale (PF scores)

- Oswestry disability index

- Roland-Morris disability index

- VAS-score: one of leg pain and one of back pain[19]

- North American Spine Society Score for neurologic symptoms[20]

- McGill pain Questionnaire[19]: this questionnaire looks at the location, intensity, quality and pattern of the pain as well as alleviating and aggrevating factors[21].

- Sciatica Frequency and Bothersome Index (SFBI)[19]: patients rate their leg pain, numbness/tingling in the leg, foot or groin, weakness in the leg/foot and back/leg pain while sitting and the frequency with which these symptoms occur on a scale of 0 (= not bothersome) to 6 (= extremely bothersome)[22].

- Prolo scale: measures the functional and economic status of the patient after undergoing surgery according to the surgeon and/or nurse involved in research[19].

- Maine – Seattle Back Questionnaire: a score between 0 and 12 is given to items concerning the back[23].

- Numeric Rating Scale: used to rate pain (such as pain in the lower back, sciatic pain…) on a scale from 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst pain imaginable”). Patients are asked to rate their current pain intensity[24].

- Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC)[24].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Acute cervical and lumbar radiculopathies due to herniated disc are primarily managed with non-surgical treatments.

- NSAIDs and physical therapy are the first-line treatment modalities.

- Translaminar epidural injections and selective nerve root blocks are the second line modalities. These are good modalities for managing disabling pain.

- Patients who fail conservative treatment or patients with neurological deficits need timely surgical consultation[7].

Surgical Treatment[edit | edit source]

As always surgical treatment is the last resort.

- Surgical treatments for a herniated disc include laminectomies with discectomies depending on the cervical or lumbar area.

- Patients with a herniated disc in the cervical spine can be managed via an anterior approach that requires anterior cervical decompression and fusion. This patient can also be managed with artificial disks replacement.

- Other alternative surgical approaches to the lumbar spine include a lateral or anterior approach that requires complete discectomy and fusion.[7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy often plays a major role in herniated disc recovery. Physiotherapy does not only offer pain relief and decreases disability [25], but it also contributes to protecting the body to prevent further injury[26]. No evidence has been found for the effectiveness of conservative treatment compared with surgery for treatment of cervical disc herniation[27]. Different studies have shown that a combination of different techniques will form the optimal treatment for a herniated disc. There is contradictory and insufficient evidence with respect to the use of traction, ultrasound and low-level laser therapy[28]. Exercise and ergonomic programs should be considered as very important components of this combined therapy[29].

The physical therapy management for patients with disc herniation can be divided into two main groups: patients with or without surgery. In case of surgery, revalidation programmes start regularly 4-6 weeks post-surgery[30].

Some patients with a herniated disc undergo an operation to reduce their symptoms. After this operation they might follow physiotherapy to support their rehabilitation. A comparison among rehabilitation programmes that start four to six weeks post-surgery with exercises versus no treatment shows that exercise programmes are more effective than no treatment in terms of short-term follow-up for pain. They also investigated the difference between high-intensity exercise programmes and low-intensity exercise programmes. There was low-quality evidence shown that high-intensity exercise programmes are slightly more effective for pain and in terms of functional status in the short term compared with low-intensity exercise programmes. However long-term follow-up results for both pain and functional status showed no significant differences between groups. Research shows no significant differences between supervised exercise programmes and home exercise programmes in terms of short-term pain relief[31].

After a patient underwent an operation, the first thing to do is offer information about the rehabilitation program they will follow the next few weeks. The patients are instructed and accompanied in daily activities such as: coming out of bed, going to the bathroom and clothing. Besides all this the patients have to pay attention on the ergonomics of the back throughout back school[32][30][33][34].

Stretching

There is low-quality evidence found to suggest that adding hyperextension to an intensive exercise programme might not be more effective than intensive exercise alone for functional status or pain outcomes. There were also no clinically relevant or statistically significant differences found in disability and pain between combined strength training and stretching, and strength training alone[31].

Behavioural Graded Activity Programme

A global perceived recovery was better after a standard physiotherapy programme than after a behavioural graded activity programme in the short term, however no differences were noted in the long term[31].

Ultrasound and Shock Wave Therapies

Ultrasound is used to penetrate the tissues and transmitting heat deep into the tissues. The aim of ultrasound is to increase local metabolism and blood circulation, enhance the flexibility of connective tissue, and accelerate tissue regeneration, potentially reducing pain and stiffness, while improving mobility. Shock wave applies vibration at a low frequency to the tissues (10, 50, 100, or 250 Hz). This causes an oscillatory pressure to decrease pain. The available evidence does not support the effectiveness of both therapy strategies for treating a herniated disc[35].

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

TENS uses an electrical current to stimulate the patients muscles. Electrodes on the skin send a tiny electrical current to key points on the nerve pathway. It is generally believed to trigger the release of endorphins, which are the body's natural pain killers and reduce muscle spasms. For this reason, TENS therapy contribute to pain relief and improvement of function and mobility of the lumbosacral spine[36].

Manipulative Treatment

Manipulative treatment on lumbar disc herniation appears to be safe, effective, and it seems to be better than other therapies. However high-quality evidence is needed to be further investigated[37].

Stabilisation Exercises/Core Stability

A strong core is important to the health of the spine. The core (abdominal) muscles help the back muscles support the spine. When your core muscles are weak, it puts extra pressure on your back muscles. So it is important to teach core stabilizing exercises to strengthen your back. It is also very important to train the endurance of these muscles. A core stability program decreases pain level, improves functional status, increases health-related quality of life and static endurance of trunk muscles in lumbar disc herniation patients[38]. Individual high-quality trials found moderate evidence that stabilisation exercises are more effective than no treatment[39].

Traction

The goal of traction is to reduce the effects of gravity on the spine. This technique is often used to relief the patient’s pain in order to facilitate the progression to an exercise program[4]. By gently pulling apart the bones, the intent is to reduce the disc herniation. It can be performed in the cervical or lumbar spine[30]. Lumbar traction may be performed in prone or supine position. When applying this kind of treatment, it is recommended to place the patient in a flexed position as it tends to open the neural foramin and to stretch the posterior elements of the back. To unload the intervertebral disc more effectively it is preferable to let the patient lay in a prone position with a correct amount of lordosis in the lower back. Usually traction will be performed with a force equal to 50% of the patient’s body weight. The total duration of the treatment should be 15 minutes with use of an intermittent force pattern of 20 to 30 seconds on and 10 to 15 seconds off[4].

A recent study has shown that traction therapy has positive effects on pain, disability and SLR on patients with intervertebral disc herniation[40].Also one trial found some additional benefit from adding mechanical traction to medication and electrotherapy[2].

Aquatic Vertical Traction

In patients with low back pain and signs of nerve root compression this method had greater effects on spinal height, the relieving of pain, lowering the centralisation response and lowering the intensity of pain than the assuming of a supine flexing position on land[41].

Hot and Cold Therapies

These offer their own set of benefits, and your physical therapist may alternate between them to get the best results. Your physical therapist may use heat to increase blood flow to the target area. Blood helps heal the area by delivering extra oxygen and nutrients. Blood also removes waste byproducts from muscle spasms[10].

- Cryotherapy can be used to suppress the metabolism of the tissue after joint surgery, because of the decrease in tissue temperature. This leads to a lessening of pain, edema and postoperative bleeding, and also helps postoperative recovery of range of motion much more rapidly. For patients who underwent one level microendoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc herniation the Icing System CF3000 can be used as it can be used to cool the spine when in a supine position or when lying on the side[42].

Muscle Strengthening

Strong muscles are a great support system for your spine and better handle pain. If core stability is totally regained and fully under control, strength and power can be trained. But only when this is necessary for the patients functioning/activities. This power needs to be avoided during the core stability exercises because of the combination of its two components: force and velocity. This combination forms a higher risk to gain back problems and back pain[28].

Traditional Chinese Medicine for Low Back Pain (TCM)

TCM has been demonstrated to be effective. Reviews have demonstrated that acupressure, acupuncture and cupping can be efficacious in pain and disability for chronic low back pain included disc herniation[4][5].

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Mobilization

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and mobilization (MOB) leads to short-term pain relief when suffering from acute low back pain. When looking at chronic low back pain, SMT has an effect similar to NSAID[6].

Dynamic Lumbar Stabilization Exercises

Exercises which include techniques such as dynamic abdominal girdle and methods for finding and maintaining neutral lumbar position during daily activities. The emphasis is here placed on the multifidus and the transversus abdominis muscle. The multifidus plays a role in the protection of the lumbar region against involuntary movements and torsion forces as it contributes to spine stabilisation. On the other side the transversus abdominis assists to lumbar stability through increased abdominal pressure by acting like a belt around the abdomen[33].

Example of Protocol for Rehabilitation Following a Lumbar Microdiscectomy

The following program is an example of a protocol for rehabilitation following a lumbar microdiscectomy[33]:

- Duration of rehabilitation program: 4 weeks

- Frequency: every day

- Duration of one session: approximately 60 minutes

- Treatment: dynamic lumbar stabilization exercises + home exercises

- Exercises: Prior to the DLS training session patients are provided with instruction or technique to ensure and protect a neutral spine position. During the first 15 minutes of each session stretching of back extensors, hip flexors, hamstrings and Achilles tendon should be performed.

DLS consists of:- Quadratus exercises

- Abdominal strengthening

- Bridging with ball

- Straightening of external abdominal oblique muscle

- Lifting one leg in crawling position

- Lifting crossed arms and legs in crawling position

- Lunges

Home Exercises

A home exercise programme should be added to the treatment. These should be performed every day.

Modalities: 5 repetitions during the first week up to 10-15 reps in the following weeks

Aerobic Training

A study has been conducted to analyse the effect of an aerobic training program on post-operative patients. One month after the surgery, the patients received a supervised treadmill exercise next to the home exercise program. The treadmill exercise consisted of a walk of 30 minutes on the treadmill without inclination five times a week with tolerated speed during four weeks. The speed of walking was increased once the patient’s tolerance was considered as high enough. The conclusion is that aerobic exercise-based rehabilitation program in combination with home exercises starting one month after first-time single-level lumbar microdiscectomy has a positive effect on functionality than only a home exercise program. However the authors of the study point out that more studies should be conducted concerning aerobic exercise programs in post-operative patients[43].

Lumbar Tender Point Deep Massage

When used in combination with lumbar traction, this method resulted in a higher pain threshold, less muscle hardness and less intense pain in patients with chronic non-specific lower back pain than lumbar traction on its own[44].

Conservative therapy for cervical spine [45] According to the systematic review of Gross A.:

- Cervical manipulation VS inactive control (subacute- chronic): gives immediate pain relief but not on short term follow-up.

- Cervical manipulation VS cervical mobilization (acute- chronic): decline in pain, better QoL and GPE

- Cervical manipulation VS medication: (acute- subacute): better function of neck, more decline in pain

- Cervical manipulation Vs massage (chronic): decline in pain, better function

This concludes that cervical manipulation may give better results in decline in pain and better function than inactive control, cervical mobilization, medication and massage.

The systematic review Bronfort did on spinal manipulative therapy (SMT)concluded that for chronic neck pain that SMT and mobilization may give more pain reduction then a general practitioner management on short term follow-up but similar pain relief like high-technology rehabilitative exercise in the short and long term. In a mix of acute and chronic patients there is limited evidence that SMT, in both the short and long term, is inferior to physical therapy[46].

Clinical Bottom line[edit | edit source]

Intervertebral disc herniation is one of most common diseases that produces low back pain and/or leg pain in adults. It often occurs as a result of age-related degeneration of the annulus fibrosis. Disc herniation are most of the time asymptomatic and 75% of the intervertebral disc herniation recover spontaneously within 6 months.

Disc herniation can occur at different levels in the spine. A herniated disc affects most commonly the lumbar discs between vertebra L4-L5 and L5-S1. Cervical disc herniation are more rare than lumbar disc degeneration. The cervical disc herniation is most locate at level C5-C6 and C6-C7.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kerr, Dana, Wenyan Zhao, and Jon D. Lurie. "What are long-term predictors of outcomes for lumbar disc herniation? A randomized and observational study." Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 473.6 (2015): 1920-1930. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jordan, Jo, Kika Konstantinou, and John O'Dowd. "Herniated lumbar disc." BMJ clinical evidence 2011 (2011). Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ McGill, S. (2007). Low Back Disorders: Evidence Based Prevention and Rehabilitation, Second Edition. USA: Human Kinetics. Level of evidence: 3B

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Olson K., Manual Physical Therapy of Spine, Saunders Elsevier, 2009, p114-116

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jioun Choi MS., Influences of spinal decompression therapy and general traction therapy on the pain, disability, and straight leg raising of patients with intervertebral disc herniation, J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Feb; 27(2): 481–483. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Demir S., Effects of dynamic lumbar stabilization exercises following lumbar microdiscectomy on pain, mobility and return to work. Randomized controlled trial., Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2014 Dec;50(6):627-40. Epub 2014 Sep 9. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Dulebohn SC, Massa RN, Mesfin FB. Disc Herniation.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441822/ (last accessed 25.1.2020)

- ↑ Musculoskeletal key Applied anatomy of the lumbar spine Available from:https://musculoskeletalkey.com/applied-anatomy-of-the-lumbar-spine/ (last accessed 24.1.2020)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Raj, P. Prithvi. "Intervertebral Disc: Anatomy‐Physiology‐Pathophysiology‐Treatment." Pain Practice 8.1 (2008): 18-44. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Drake, Richard, A. Wayne Vogl, and Adam WM Mitchell. Gray's anatomy for students. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014

- ↑ Lena Shahbandar and Joel Press. Diagnosis and Nonoperative Management of Lumbar Disk Herniation. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, 2005; 13: 114-121 (Level of evidence:5)

- ↑ L. G. F. Giles, K. P. Singer. The Clinical Anatomy and Management of Back Pain. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006.

- ↑ McGill, S. (2007). Low Back Disorders: Evidence Based Prevention and Rehabilitation, Second Edition. USA: Human Kinetics. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Jegede KA, etal. Contemporary management of symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41:217-24. PMID: 20399360 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20399360. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ Chou R, etal. Nonsurgical interventional therapies for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society clinical practice guideline. Spine. 2009; Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ LaxmaiahManchikanti etal; An Update of Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines for Interventional Techniques in Chronic Spinal Pain. Part II: Guidance and Recommendations. Pain Physician 2013; 16:S49-S283 • ISSN 1533-3159 Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Marcelo Gálvez M.1 , Jorge Cordovez M.1 , Cecilia Okuma P.1 , Carlos Montoya M.2, Takeshi Asahi K.2 Revista Chilena de Radiología. Vol. 23 Nº 2, año 2017; 66-76 Differential diagnoses for disc herniation. Available from:https://www.webcir.org/revistavirtual/articulos/2017/3_agosto/ch/hernia_eng.pdf (last accessed 25.1.2020)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Simeone, F.A.; Herkowitz, H.N.; Upper lumbar disc herniations. J Spinal Disord. 1993 Aug;6(4):351-9. Level of evidence: 3A

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Brouwer, Patrick A., et al. "Effectiveness of percutaneous laser disc decompression versus conventional open discectomy in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation; design of a prospective randomized controlled trial." BMC musculoskeletal disorders 10.1 (2009): 1.Level of evidence: 1b

- ↑ Van Der Windt, Daniëlle AWM, et al. "Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low‐back pain." The Cochrane Library (2010). (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Ngamkham, Srisuda, et al. "The McGill Pain Questionnaire as a multidimensional measure in people with cancer: an integrative review." Pain Management Nursing 13.1 (2012): 27- 51. Level of evidence: 2a

- ↑ Grøvle, Lars, et al. "The bothersomeness of sciatica: patients’ self-report of paresthesia, weakness and leg pain." European Spine Journal 19.2 (2010): 263-269. Level of evidence: 2c

- ↑ Haugen, Anne Julsrud, et al. "Estimates of success in patients with sciatica due to lumbar disc herniation depend upon outcome measure." European Spine Journal 20.10 (2011): 1669-1675. Level of evidence: 2c

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Lee, Jinho, et al. "Effects of Shinbaro pharmacopuncture in sciatic pain patients with lumbar disc herniation: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial." Trials 16.1 (2015): 1. Level of evidence: 1b

- ↑ . Filiz M et al. The effectiveness of exercise programmes after lumbar disc surgery: a randomized controlled study, 2005; 19, 4: 4-11. Level of evidence: 1B

- ↑ . Jason M. Highsmith, MD.; Physical therapy for herniated discs; 11/06/15; spine universe Level of evidence: 5

- ↑ Gebreariam L. et al. Evaluation of treatment effectiveness for the herniated cervical disc: systematic review. Spine, 2012;15,37: 109-18. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Wong, J. J., et al. "Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration." European Journal of Pain (2016). (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Olson K., Manual Physical Therapy of Spine, Saunders Elsevier, 2009, p114-116. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Raymond W. J. G Ostelo et al. (2009). Rehabilitation After Lumbar Disc Surgery: An update Cochrane Review. Spine Vol. 34 Nr. 17, 1839 - 1848. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Oosterhuis, Teddy, et al. "Rehabilitation after lumbar disc surgery." The Cochrane Library (2014). Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Ann-Christin Johansson, S. J. (2009). Clinic-based training in comparison to home-based training after first-time lumbar disc surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine Journal , 398-409. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Mustafa Filiz, A. C. (2005). The effectiveness of exercise programmes after lumbar disc surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 4-11. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ Cele B. Erdogmus, K.-L. R. (2007 Vol.32 Nr.19). Physiotherapy-Based Rehabilitation Following Disc Herniation Operation. Spine , 2041-2049. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ Seco, Jesús, Francisco M. Kovacs, and Gerard Urrutia. "The efficacy, safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound and shock wave therapies for low back pain: a systematic review." The Spine Journal 11.10 (2011): 966-977. Level of evidence: 1B

- ↑ Pop, T., et al. "Effect of TENS on pain relief in patients with degenerative disc disease in lumbosacral spine." Ortopedia, traumatologia, rehabilitacja 12.4 (2009): 289-300. Level of evidence: 2A

- ↑ Li, L., et al. "[Systematic review of clinical randomized controlled trials on manipulative treatment of lumbar disc herniation]." Zhongguo gu shang= China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology 23.9 (2010): 696-700. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Bayraktar D et al., A comparison of water-based and land-based core stability exercises in patients with lumbar disc herniation: a pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2015 Sep 2:1-9. Level of evidence: 3B

- ↑ . Hahne A.J. et al. Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review, Spine, 2010; 15, 35: 488-504. Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ . Jioun Choi MS., Influences of spinal decompression therapy and general traction therapy on the pain, disability, and straight leg raising of patients with intervertebral disc herniation, J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Feb; 27(2): 481–483. Level of evidence: 2B

- ↑ Simmerman, Susanne M., et al. "Immediate changes in spinal height and pain after aquatic vertical traction in patients with persistent low back symptoms: A crossover clinical trial." PM&R 3.5 (2011): 447-457. Level of evidence: 2b

- ↑ Murata, Kenji, et al. "Effect of Cryotherapy after Spine Surgery." Asian spine journal 8.6(2014): 753-758. Level of evidence: 2b

- ↑ Gerald L. Burke. "Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx". MacDonald Publishing. Retrieved 2013-02-14. Level of evidence: 5

- ↑ Zheng, Zhixin, et al. "Therapeutic evaluation of lumbar tender point deep massage for chronic non-specific low back pain." Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 32.4 (2012): 534- 537.

- ↑ Gross A, Langevin P, Burnie SJ, Bédard-Brochu MS, Empey B, Dugas E, Faber-Dobrescu M, Andres C, Graham N, Goldsmith CH, Brønfort G, Hoving JL, LeBlanc F. Manipulation and mobilisation for neck pain contrasted against an inactive control or another active treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004249. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004249.pub4 (LOE: 1B)

- ↑ Bronfort G. et al. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004 May-Jun;4(3):335-56. PMID: 15125860 DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.06.002 (LOE: 1B)