Depression

Original Editors - Nadine Risman from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Nadine Risman, Tessa Larimer, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Tolulope Adeniji, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Elaine Lonnemann, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Vidya Acharya, Manisha Shrestha, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Amanda Ager, Lauren Lopez and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Depression is a common illness worldwide, with more than 264 million people affected. Depression is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. Especially when long-lasting and with moderate or severe intensity, depression may become a serious health condition. It can cause the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work, at school and in the family. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide[1].

Because of false perceptions, nearly 60% of people with depression do not seek medical help. Many feel that the stigma of a mental health disorder is not acceptable in society and may hinder both personal and professional life. There is good evidence indicating that most antidepressants do work but the individual response to treatment may vary.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

| [3] |

While the exact cause of depression isn’t known, a number of things can be associated with its development. Generally, depression does not result from a single event, but from a combination of biological, psychological, social and lifestyle factors[4].

- First-degree relatives of depressed individuals are about 3 times as likely to develop depression as the general population; however, depression can occur in people without family histories of depression.

- Some evidence suggests that genetic factors play a lesser role in late-onset depression than in early-onset depression.

- Neurodegenerative diseases (especially Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease), stroke, multiple sclerosis, seizure disorders, cancer, macular degeneration, and chronic pain have been associated with higher rates of depression.

- Life events and hassles operate as triggers for the development of depression.

- Environmental factors: Continuous exposure to violence, neglect, abuse or poverty may make some people more vulnerable to depression.[5]

- Traumatic events eg death or loss of a loved one, lack of social support, caregiver burden, financial problems, interpersonal difficulties[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Depression is a common illness worldwide, with more than 264 million people affected. Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease.[1]

- Twelve-month prevalence of major depressive disorder is approximately 7%, with marked differences by age group.

- The prevalence in 18- to 29-year-old individuals is threefold higher than the prevalence in individuals aged 60 years or older.

- Close to 800 000 people die due to suicide every year. Suicide is the second leading cause of death in 15-29-year-olds[1]

- Females experience 1.5- to 3-fold higher rates than males beginning in early adolescence.[2]

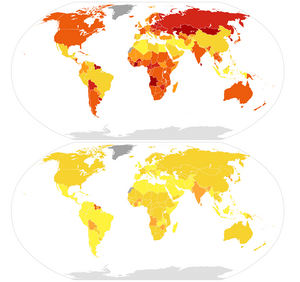

Image 2: World map illustration of male (top) and female (bottom) suicide mortality rates per 100,000 individuals in 2015, as per data by World Health Organization (rev. April 2017). 0 - 5 yellow working up to above 35 dark red.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Depression causes feelings of sadness and/or a loss of interest in activities once enjoyed. It can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems and can decrease the persons ability to function at work and at home.

Depression symptoms can vary from mild to severe and can include:

- Feeling sad or having a depressed mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed

- Changes in appetite — weight loss or gain unrelated to dieting

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

- Loss of energy or increased fatigue

- Increase in purposeless physical activity (e.g., inability to sit still, pacing, handwringing) or slowed movements or speech (these actions must be severe enough to be observable by others)

- Feeling worthless or guilty

- Difficulty thinking, concentrating or making decisions

- Thoughts of death or suicide

Symptoms must last at least two weeks and must represent a change in your previous level of functioning for a diagnosis of depression[5].

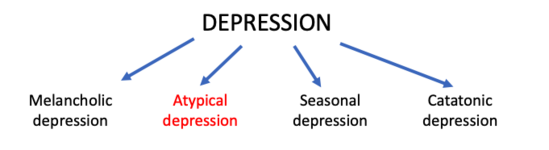

Classification[edit | edit source]

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies the depressive disorders into:

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Major depressive disorder

- Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Depressive disorder due to another medical condition

The common features of all the depressive disorders are sadness, emptiness, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function.[2]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There are effective treatments for moderate and severe depression.

- Health-care providers may offer psychological treatments eg behavioural activation, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), or antidepressant medication such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

- Health-care providers should keep in mind the possible adverse effects associated with antidepressant medication, the ability to deliver either intervention (in terms of expertise, and/or treatment availability), and individual preferences.

- Different psychological treatment formats for consideration include individual and/or group face-to-face psychological treatments delivered by professionals and supervised lay therapists.

- Psychosocial treatments are also effective for mild depression.

- Antidepressants can be an effective form of treatment for moderate-severe depression but are not the first line of treatment for cases of mild depression. They should not be used for treating depression in children and are not the first line of treatment in adolescents, among whom they should be used with extra caution.[1]

Outcome Measures examples[edit | edit source]

- The Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition: 21 item self-report form that is intended to assess the existence and severity of symptoms of depression in adults and adolescents 13 year and older. The patient should answer the questions based on how they have felt for the last 2 weeks. There is a version of this test that can be used for medical patients that is a seven item self-report measure of depression in adolescents and adults that reflects the cognitive and affective symptoms of depression while excluding somatic and performance symptoms that might be attributable to other conditions. When scoring the Beck the higher the score the higher the feelings of depression are. All of the Beck Scales have been validated in assisting health care professionals in making focused and reliable client evaluations.

- Geriatric Depression Scale - 15 (short form): 15 yes/no question self-report form that the patient answers based off how they have felt over the last week. Each question is worth one point. The GDS-15 with a cutoff score of 6 has 94% sensitivity and 85% specificity in community dwelling older adults. With a cutoff score of 5 the GDS-15 has 72% sensitivity and 78% specificity in home care patients[6].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

One of the biggest things a physical therapist can do for their patients is to be aware of the signs and symptoms of depression and some of the common disorders associated with depression. If the therapist is sensitive to the signs and symptoms of depression they can document it in the plan of care and then notify the physician so the patient can get the appropriate medical treatment, if necessary. Also, because patients with depression may be emotionally unstable, recognizing the signs and symptoms of depression can help you in approaching different situations and then redirecting the patient toward other activities, instructions or more positive topics of conversation.

- Exercise has been shown to benefit patients with mild to moderate mood disorders, especially anxiety and depression.

- When performing aerobic exercise your body releases endorphins from the pituitary gland which are responsible for relieving pain and improving mood. These endorphins can also lower cortisol levels which have been shown to be elevated in patients with depression.

- Exercise increases the sensitivity of serotonin in the same way antidepressants work, allowing for more serotonin to remain in the nerve synapse.

- Exercise is an excellent option for treatment when taking anti-depressants is not an option due to their side effects. Depression symptoms can be decreased significantly after just one session but the effects are temporary.

- An exercise program must be continued on a daily basis to see continued effects. As a person continues to exercise they may experiences changes in their body type which can help to improve self esteem and body image issues they may have been having.

- Some other benefits of regular physical exercise include:[7]Reduces/prevents functional declines associated with ageing; Maintains/improves cardiovascular function; Aids in weight loss and weight control; Improves sleep pattern

Because of depression’s effect on the neuromusculoskeletal system, research has shown that treating a patient’s underlying depression can lead to better improvements in their pain.

Physical therapists can implement other strategies into their practice to further improve the effects of therapy beyond the benefits of exercise. Research has determined that a further decrease in depression symptoms can be obtained in the clinic by utilizing principles from the following:

- Mindfulness[7]

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy [8][9]

- Norwegian Psychomotor Physical Therapy [10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Depression is a disease that tends to hide itself among other diseases. Also, because depression tends to present with somatic pain, rather than emotional responses, physical therapists should be aware of red flags that could signal their complaints are of non-musculoskeletal origin. If the physical therapist is unable to reproduce or relieve the patients pain the cause of the pain may be of non-musculoskeletal origin and the patient should be referred on to the appropriate health care provider. Also performing a thorough screening of the patient and their past medical history will help to guide your decision on whether the patient’s complaints are with in the scope of practice for physical therapists.

Differential Dx include:

- Anaemia

- Chronic Fatigue syndrome

- Dissociative disorders

- Illness anxiety disorders

- Hypoglycemia

- Schizophrenia

- Somatic symptom disorders[2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 WHO Depression Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Chand SP, Arif H. Depression. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430847/ (Accessed, 12/9/2021).

- ↑ Depression - it's causes. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJKSfRKBzw0 [last accessed 4/10/17]

- ↑ Better health Depression Available: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/depression (accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 American Psychiatric Association Depression Available: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/what-is-depression(accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ Vieira ER, Brown E, Raue P. Depression in older adults: screening and referral. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2014 Jan 1;37(1):24-30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. The Psychological Spiritual Impact on Health Care. In: 3rd ed: Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009: 110-115.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anxiety and Depression. CDC Features. March 13, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Features /dsBRFSS Depression Anxiety/. Accessed on March 2, 2010.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Snyder TK. Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns. In: 4th ed: Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: 153-157.

- ↑ Jacobsen LN, Lassen IS, Friis P, Videbech P, Licht RW. Bodily symptoms in moderate and severe depression. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):294–8.