Depression

Original Editors - Nadine Risman from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Nadine Risman, Tessa Larimer, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Tolulope Adeniji, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Elaine Lonnemann, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Vidya Acharya, Manisha Shrestha, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Amanda Ager and Lauren Lopez

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Depression is a common illness worldwide, with more than 264 million people affected. Depression is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. Especially when long-lasting and with moderate or severe intensity, depression may become a serious health condition. It can cause the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work, at school and in the family. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide[1].

Because of false perceptions, nearly 60% of people with depression do not seek medical help. Many feel that the stigma of a mental health disorder is not acceptable in society and may hinder both personal and professional life. There is good evidence indicating that most antidepressants do work but the individual response to treatment may vary.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

While the exact cause of depression isn’t known, a number of things can be associated with its development. Generally, depression does not result from a single event, but from a combination of biological, psychological, social and lifestyle factors[3].

- First-degree relatives of depressed individuals are about 3 times as likely to develop depression as the general population; however, depression can occur in people without family histories of depression.

- Some evidence suggests that genetic factors play a lesser role in late-onset depression than in early-onset depression.

- Neurodegenerative diseases (especially Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease), stroke, multiple sclerosis, seizure disorders, cancer, macular degeneration, and chronic pain have been associated with higher rates of depression.

- Life events and hassles operate as triggers for the development of depression.

- Environmental factors: Continuous exposure to violence, neglect, abuse or poverty may make some people more vulnerable to depression.[4]

- Traumatic events eg death or loss of a loved one, lack of social support, caregiver burden, financial problems, interpersonal difficulties[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Depression is a common illness worldwide, with more than 264 million people affected. Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease.[1]

- Twelve-month prevalence of major depressive disorder is approximately 7%, with marked differences by age group.

- The prevalence in 18- to 29-year-old individuals is threefold higher than the prevalence in individuals aged 60 years or older.

- Close to 800 000 people die due to suicide every year. Suicide is the second leading cause of death in 15-29-year-olds[1]

- Females experience 1.5- to 3-fold higher rates than males beginning in early adolescence.[2]

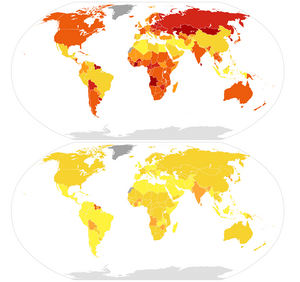

Image 2: World map illustration of male (top) and female (bottom) age-standardizedα suicide mortality rates per 100,000 individuals in 2015, as per data by World Health Organization (rev. April 2017). 0 - 5 yellow working up to above 35 dark red.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Depression causes feelings of sadness and/or a loss of interest in activities once enjoyed. It can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems and can decrease the persons ability to function at work and at home.

Depression symptoms can vary from mild to severe and can include:

- Feeling sad or having a depressed mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed

- Changes in appetite — weight loss or gain unrelated to dieting

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

- Loss of energy or increased fatigue

- Increase in purposeless physical activity (e.g., inability to sit still, pacing, handwringing) or slowed movements or speech (these actions must be severe enough to be observable by others)

- Feeling worthless or guilty

- Difficulty thinking, concentrating or making decisions

- Thoughts of death or suicide

Symptoms must last at least two weeks and must represent a change in your previous level of functioning for a diagnosis of depression[4].

Classification[edit | edit source]

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies the depressive disorders into:

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Major depressive disorder

- Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Depressive disorder due to another medical condition

The common features of all the depressive disorders are sadness, emptiness, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function.[2]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There are effective treatments for moderate and severe depression.

- Health-care providers may offer psychological treatments eg behavioural activation, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), or antidepressant medication such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

- Health-care providers should keep in mind the possible adverse effects associated with antidepressant medication, the ability to deliver either intervention (in terms of expertise, and/or treatment availability), and individual preferences.

- Different psychological treatment formats for consideration include individual and/or group face-to-face psychological treatments delivered by professionals and supervised lay therapists.

- Psychosocial treatments are also effective for mild depression.

- Antidepressants can be an effective form of treatment for moderate-severe depression but are not the first line of treatment for cases of mild depression. They should not be used for treating depression in children and are not the first line of treatment in adolescents, among whom they should be used with extra caution.[1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are also several questionnaires that can be used to help determine if a patient is at risk for developing or has depression. The results of the questionnaire can help direct a patient’s referral to more qualified health care professionals. The following are a few examples of depression questionnaires.

The Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition[edit | edit source]

21 item self-report form that is intended to assess the existence and severity of symptoms of depression in adults and adolescents 13 year and older. The patient should answer the questions based on how they have felt for the last 2 weeks. There is a version of this test that can be used for medical patients that is a seven item self-report measure of depression in adolescents and adults that reflects the cognitive and affective symptoms of depression while excluding somatic and performance symptoms that might be attributable to other conditions. When scoring the Beck the higher the score the higher the feelings of depression are. All of the Beck Scales have been validated in assisting health care professionals in making focused and reliable client evaluations.

Geriatric Depression Scale - 15 (short form)[edit | edit source]

15 yes/no question self-report form that the patient answers based off how they have felt over the last week. Each question is worth one point. The GDS-15 with a cutoff score of 6 has 94% sensitivity and 85% specificity in community dwelling older adults. With a cutoff score of 5 the GDS-15 has 72% sensitivity and 78% specificity in home care patients[5].

| [6] |

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

One of the biggest things a physical therapist can do for their patients is to be aware of the signs and symptoms of depression and some of the common disorders associated with depression. If the therapist is sensitive to the signs and symptoms of depression they can document it in the plan of care and then notify the physician so the patient can get the appropriate medical treatment, if necessary. Also, because patients with depression may be emotionally unstable, recognizing the signs and symptoms of depression can help you in approaching different situations and then redirecting the patient toward other activities, instructions or more positive topics of conversation.

Exercise has been shown to benefit patients with mild to moderate mood disorders, especially anxiety and depression. When performing aerobic exercise your body releases endorphins from the pituitary gland which are responsible for relieving pain and improving mood. These endorphins can also lower cortisol levels which have been shown to be elevated in patients with depression. Additionally, exercise increases the sensitivity of serotonin in the same way antidepressants work, allowing for more serotonin to remain in the nerve synapse. Exercise can be aerobic or resistive in nature, as both have been shown to be beneficial in a variety of patient types. Anyone with depression can participate in an exercise program no matter how old or young they are, as long as proper supervision is provided. Exercise is an excellent option for treatment when taking anti-depressants is not an option due to their side effects. Depression symptoms can be decreased significantly after just one session but the effects are temporary. An exercise program must be continued on a daily basis to see continued effects. As a person continues to exercise they may experiences changes in their body type which can help to improve self esteem and body image issues they may have been having. Some other benefits of regular physical exercise include:[7]

- Reduces/prevents functional declines associated with ageing

- Maintains/improves cardiovascular function

- Aids in weight loss and weight control

- Improves function of hormonal, metabolic, neurologic, respiratory, and hemodynamic systems

- Alteration of carbohydrate/lipid metabolism results in favourable increase in high-density lipoproteins

- Strength training helps to maintain muscle mass and strength

- Reduces age-related bone loss; reduction in risk for osteoporosis

- Improves flexibility, postural stability, and balance; reduction in risk of falling and associated injuries

- Psychological benefits (preserves cognitive function, alleviates symptoms/behaviours of depression, improves self awareness, promotes sense of well-being)

- Reduces disease risk factors

- Improves functional capacity

- Improves immune function

- Reduces age-related insulin resistance

- Reduces incidence of some cancers

- Contributes to social integration

- Improves sleep pattern

Because of depression’s effect on the neuromusculoskeletal system, research has shown that treating a patient’s underlying depression can lead to better improvements in their pain. Physical therapists can implement other strategies into their practice to further improve the effects of therapy beyond the benefits of exercise. Research has determined that a further decrease in depression symptoms can be obtained in the clinic by utilizing principles from the following:

- Mindfulness[7]

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy [8][9]

- Norwegian Psychomotor Physical Therapy [10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Depression is a disease that tends to hide itself among other diseases. The chart presented above, in the associated co-morbities section, lists numerous diseases that are associated with depression. If you are treating patients with these diagnoses, it would be wise for you to watch for changes in emotional and behavioral status. Also, because depression tends to present with somatic pain, rather than emotional responses, physical therapists should be aware of red flags that could signal their complaints are of non-musculoskeletal origin. If the physical therapist is unable to reproduce or relieve the patients pain the cause of the pain may be of non-musculoskeletal origin and the patient should be referred on to the appropriate health care provider. Also performing a thorough screening of the patient and their past medical history will help to guide your decision on whether the patient’s complaints are with in the scope of practice for physical therapists.

Guidelines for Physical Referral[9][edit | edit source]

General Systemic[edit | edit source]

- Unknown cause of pain

- Lack of significant objective neuromusculoskeletal signs and symptoms

- Lack of expected progress with physical therapy intervention

- Development of constitutional symptoms or associated signs and symptoms any time during the episode of care

- Discovery of significant past medical history unknown to physician

- Changes in health status that persist 7 to 10 days beyond expected time period

- Client who is jaundiced and has not been diagnosed or treated

For Women[edit | edit source]

- Low back, hip, pelvic, groin, or sacroiliac symptoms without know etiologic basis and in the presence of constitutional symptoms

- Symptoms correlated with menses

- Any spontaneous uterine bleeding after menopause

- For pregnant women: vaginal bleeding, elevated blood pressure, increased Braxton-Hicks contractions during exercise

Vital Signs (report findings)[edit | edit source]

- Persistent rise or fall of blood pressure

- Blood pressure elevation in women taking birth control pills

- Pulse amplitude that fades with inspiration and strengthens with expiration

- Pulse increase of 20 beats per minute lasting more than 3 minutes after rest or changing position

- Difference in pulse pressure of more than 40mmHg

- Persistent low grade fever, especially if associated with constitutional symptoms

- Unexplained fever without other systemic symptoms, especially those taking corticosteroids

Cardiac[edit | edit source]

- More than 3 sublingual nitroglycerin tablets required to gain relief from angina

- Increase in angina intensity after stimulus has been removed

- Changes in pattern of angina

- Abnormally severe chest pain

- Anginal pain that radiates to jaw/left arm

- Abnormally cool or sweaty upper back

- Heart palpitations or arrhythmias present

- Worsening dyspnea

- Fainting without any warning

Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Changes in bowel or bladder habits

- A sore that does not heal in 6 weeks

- Unusual bleeding or discharge

- Thickening or lump in breast or elsewhere (painful or painless)

- Indigestion or difficulty in swallowing

- Nagging cough or hoarseness

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Changes in deep tendon reflexes

- Bone pain, especially on weight bearing that persists more than 1 week and is worse at night

- Any unexplained bleeding from any area

Pulmonary[edit | edit source]

- Shoulder pain aggravated by respiratory movements

- Shoulder pain that is aggravated by supine positioning

- Shoulder or chest pain that subsides with auto splinting

- Signs of asthma or abnormal bronchial activity during exercise

- Weak and rapid pulse accompanied by fall in blood pressure

- Presence of associated signs and symptoms such as persistent cough, dyspnea, or constitutional symptoms

Genitourinary[edit | edit source]

- Abnormal urine output (color, odor, amount, flow of urine)

- Any blood in urine

- Cervical spine pain accompanied by incontinence

Gastrointestinal[edit | edit source]

- Back pain and abdominal pain at the same level, especially when accompanied by constitutional symptoms

- Back pain of unknown cause in a person with a history of cancer

- Back pain or shoulder pain in a person taking NSAIDS, especially when accompanied by GI upset or blood in stools

- Back or shoulder pain associated with meals or back pain relieved by a bowel movement

Musculoskeletal[edit | edit source]

- Symptoms that are out of proportion to the injury or symptoms persisting beyond the expected time for the nature of the injury

- Severe or progressive back pain accompanied by constitutional symptoms, especially fever

- New onset of joint pain following surgery with inflammatory signs (red, hot, swollen and tender)

In the older adult musculoskeletal problems can be caused from drugs or depression. This makes diagnosis and treatment of symptoms difficult. Family members can confuse the signs and symptoms of depression with those of dementia. When comparing depression and dementia, you tend to see faster declines in mental function, difficulty concentrating and memory loss in patients with depression. Patients who have dementia are more disorientated and have trouble with short term memory. Also they tend to be indifferent to their memory loss.[9]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

Moras, Karla; Telfer, Leslie A.; Barlow, David H. Efficacy and specific effects data on new treatments: A case study strategy with mixed anxiety-depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Vol 61(3), Jun 1993, 412-420.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Geriatric Depression Scale (Short Form)

National Depression Screening Day

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance

National Mental Health Association

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 WHO Depression Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Chand SP, Arif H. Depression. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430847/ (accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ Better health Depression Available: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/depression (accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 American Psychiatric Association Depression Available: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/what-is-depression(accessed 12.9.2021)

- ↑ Viera ER. Depression in Older Adults: Screening and Referral. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2014Jan;37(1):24–30.

- ↑ Depression - it's causes. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJKSfRKBzw0 [last accessed 4/10/17]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. The Psychological Spiritual Impact on Health Care. In: 3rd ed: Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009: 110-115.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anxiety and Depression. CDC Features. March 13, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Features /dsBRFSS Depression Anxiety/. Accessed on March 2, 2010.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Goodman CC, Snyder TK. Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns. In: 4th ed: Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: 153-157.

- ↑ Jacobsen LN, Lassen IS, Friis P, Videbech P, Licht RW. Bodily symptoms in moderate and severe depression. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):294–8.