Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

Original Editors - Katelyn Koeninger & Kristen Storrie from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Katelyn Koeninger, Kristen Storrie, Laura Ritchie, Yves Hubar, Laure-Anne Callewaert, Angeliki Chorti, Admin, Melissa Coetsee, Evan Thomas, Scott Cornish, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Gwen Wyns, Matthias Steenwerckx, Vidya Acharya, Claire Knott, Lauren Lopez, Jo Etherton, Wendy Walker, Naomi O'Reilly, Maria Galve Villa, Michelle Lee, Richmond Stace and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a term for a variety of clinical conditions characterized by chronic persistent pain. It is a disease that may develop after a limb trauma. [1] This appears mostly in 1 or more limbs, usually in the arms or legs. We can say a CRPS is a regional posttraumatic neuropathic pain problem.[2] Neuropathic pain disorders are a disproportionate consequence of painful trauma or nerve lesion. [3]

CRPS is subdivided into type I and type II CRPS.

In the literature, there are a lot of names used to describe this syndrome such as ‘‘Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy’’, ‘‘causalgia’’, ‘‘algodystrophy’’, ‘‘Sudeck’s atrophy’’, ‘‘neurodystrophy’’, and ‘‘post-traumatic dystrophy’’. To standardize the nomenclature, the name ‘complex regional pain syndrome’ was adopted in 1995 by the ‘International Association for the Study of Pain’ (IASP). [4]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

CPRS affects approximately 26 out of every 100,000 people. It is more common in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1.[5] CRPS can affect people of all ages, including children as young as three years old and adults as old as 75 years old, but typically is most prevalent beginning in the mid-thirties. CRPS type I occurs after five percent of all traumatic injuries.[6] Ninety-one percent of all CRPS cases occur after surgery.[7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs and Symptoms of CRPS:

- pain (pain may not be present in 7%of CRPS sufferers)[6] [5][8]

- swelling[6][5][8]

- tremor[6]

- trouble initiating movements[6]

- muscle spasms (may be present in the cervical and lumbar spine regions in advanced cases)[6][8]

- muscle atrophy[6]

- temperature changes[6][5]

- color changes (red, blue)[6]

- thick, brittle, or rigid nails[6]

- weakness[6][5][8]

- thin, shiny, clammy skin[5]

- stiffness or decreased joint motion[5]

- painful or decreased sensation on skin (some patients report intolerance to air moving over skin)[5]

- strange, disfigured, or dislocated feelings in limbs[5]

Characteristics:

- sensory impairments[6]

- movement disorders, typically in contralateral extremity[6][8]

- ANS dysfunction[6]

- dystrophy[6]

- atrophy[6]

- spreads proximally, to other extremities, and possibly the entire body[6]

- similar presentation to osteoporosis on radiographic images[6]

Patients typically progress through three stages as CRPS develops. CRPS in children does not always follow the same stage patterns and may at times become stagnate or even slowly improve.[8]

| Stage | Time Period | Classic Signs and Symptoms[6] |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I: acute inflammation: denervation and sympathetic hypoactivity | Begins 10 days post injury; Lasts 3-6 months |

Pain: more severe than expected; burning or aching; increased with dependent position, physical condition, or emotional disturbances Hyperalgesia, allodynia, hyperpathia: lower pain threshold, increased sensitivity, all stimuli are perceived as painful, increased pain threshold then increased sensation intensity (faster and greater pain) Edema: soft and localized Vasomotor/Thermal Changes: warmer Skin: hyperthermia, dryness Other: increased hair and nail growth |

| Stage II: dystrophic: paradoxic sympathetic hyperactivity | Begins 3-6 months after onset of pain; Lasts about 6 months |

Pain: worsens, constant, burning, aching Hyperalgesia, allodynia, hyperpathia: present Edema: hard, causes joint stiffness Vasomotor/Thermal Changes: none Skin: thin, glossy, cool due to vasoconstriction, sweaty Other: thin & rigid nails, osteoporosis and subchondral bone erosion noted on x-rays |

| Stage III: atrophic | Begins 6-12 months after onset of pain; Lasts for years, or may resolve and reappear |

Pain: spreads proximally and occasionally to entire body, may plateau Edema: hardening Vasomotor/Thermal Changes: decreased SNS regulation, cooler Skin: thin, shiny, cyanotic, dry Other: fingertips and toes are atrophic, thick fascia, possible contractures, demineralization and ankylosis seen on x-rays |

[9]

[edit | edit source]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

CRPS may also be associated with:

- Arterial Insufficiency[10]

- Asthma[5]

- Bone Fractures[8]

- Cellulitis[10]

- Central Pain Syndromes[10]

- Conversion Disorder[10]

- Depression/Anxiety

- Factitious Disorder [10]

- Lymphedema[10]

- Malignancy[10]

- Migraines[5]

- Nerve Entrapment Syndromes[10]

- Osteomyelitis[10]

- Osteoporosis[5][8]

- Pain Disorder[10]

- Peripheral Neuropathies[10]

- Rheumatoid Arthritis[10]

- Scleroderma[10]

- Septic arthritis[10]

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus[10]

- Tenosynovitis[10]

- Thrombophlebitis[10]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Possible treatments for CRPS include:

- Oral pain-relieving medications including corticosteroids and NSAIDs, as well as acupuncture provide effective pain relief in approximately 20% of those with CRPS, but this is supported by weak evidence.[6]

- Treatments may be geared to helping patients manage symptoms. Amitriptyline relieves depression and acts as a sleeping aid. Calcium channel blockers can help to improve circulation through SNS effect. Intrathecal baclofen, among other measures, improves motor dystonia.[6]

- Pain intensity and perception of pain is sometimes relieved through use of an implanted transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit.[6]

- A randomized double dummy controlled, double blind trial compared the effectiveness of Dimethylsulfoxide 50% (DMSO) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in treating CRPS type I. There were no significant differences between the two treatments, but are both successful treating CRPS type I. This study showed that DMSO-treatment is more favorable for warm CRPS whereas NAC is more favorable for cold CRPS[11]

- Low doses of ketamine infusion has been shown to decrease pain in patients with CRPS type I who had been unsuccessful with other conservative methods of management. Ketamine blocks central sensitization by effecting the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor which has been shown to be effected in CRPS.[12]

- Antidepressants may be utilized to treat associated depression.[8]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of CRPS is based solely on examination and patient history.[6] A triple-phase bone scan is the best method to rule out type I CPRS.[13] According to Cappello, the triple-phase bone scan has the best sensitivity, NPV, and PPV compared to MRI and plain film radiographs.[13] Radiographic examinations, laser Doppler flowmetry, and thermographic studies may be utilized to assess the secondary issues and symptoms of CRPS.[6]

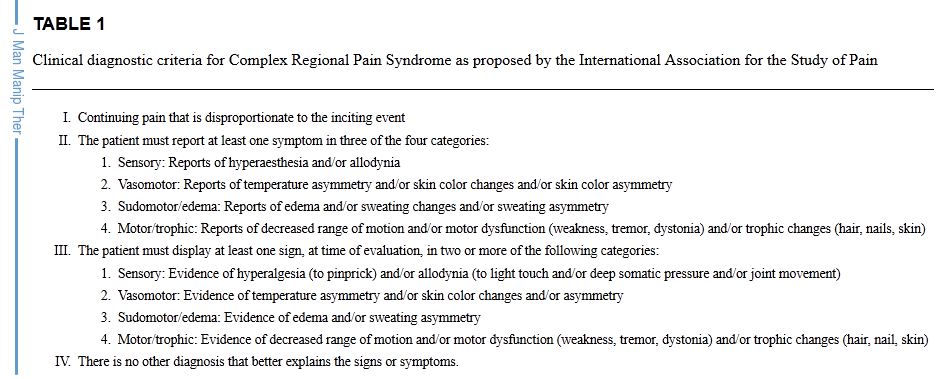

The Budapest Criteria

The Budapest Criteria have been used to diagnose CRPS as well. This method has high specificity and sensitivity according to Goebel.[5]

To make the clinical diagnosis, the following criteria must be met:

1. Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

2. Must report at least one symptom in three of the four following categories:

- Sensory: Reports of hyperesthesia and/or allodynia

- Vasomotor: Reports of temperature asymmetry and/or skin color changes and/or skin color asymmetry

- Sudomotor/Edema: Reports of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/Trophic: Reports of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

3. Must display at least one sign at time of evaluation in two or more of the following categories:

- Sensory: Evidence of hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch and/or temperature sensation and/or deep somatic pressure and/or joint movement)

- Vasomotor: Evidence of temperature asymmetry (>1 °C) and/or skin color changes and/or asymmetry

- Sudomotor/Edema: Evidence of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/Trophic: Evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

4. There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The cause of CRPS remains unknown, however there are explanations for the presentation of the condition. After trauma or external stresses placed on the body, the nervous system has a heightened response to stimuli.[14] The inflammatory process of the body overreact leading to red hot extremities due to exaggerated blood supply to the area, or blue, cold extremities due to blood vessel constriction.[8]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

CRPS primarily affects the vascular system, but over time it can spread to other systems including the nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular systems. Problems develop such as headache, dizziness, tinnitus, urgency/frequency of urination, erection disturbances, renal bleeding, hypertension, nose bleeds, syncope, abdominal pain, peptic ulcers, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, diarrhea, chest pain, abnormal heart beat, tachycardia, heart attack, and falls.[8]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

- Spinal cord stimulation was more effective than conventional medical management in reducing pain in patients with CRPS type I[16]

- Spinal cord stimulation was shown to be effective in completely eliminating pain in adolescent females 2-6 weeks after stimulation[17]

- Use of surgical and chemical sympathectomy show moderate improvement in pain scores in patients with CRPS. There were no significant differences found between the surgical and chemical groups when comparing pain scores from day one to four months. More high quality research needs to be done before recommending this as a first line of defense.[18]

- High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the motor cortex in addition to pharmacological management was effective in reducing pain. This was demonstrated by the scores on the McGill Pain Questionnaire and Short Form-36 which include different aspects of pain such as sensory-discriminative and emotional-affective.[19]

- Surgery, casts, and ice should be avoided when treating CRPS because they further aggravate the nervous system. Surgery leads to further stress, inflammation, and immune system disturbances.[8]

- A stellate ganglion block, or sympathectomy, blocks the nerve pathways causing pain. This may be most beneficial in the early stages of CRPS.[6][5]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

It has been found that physical therapy and occupational therapy are effective in reducing pain and increasing function in patients who have had CRPS for less than 1 year[5]. Physical therapy should focus on patient education of CRPS and functional activities. The typical preferred practice patterns for CRPS are as follows: 4A, 4D, 5G, and 7B.[6]

Physical therapy intervention could include any of the following:

- TENS: Somers, et al found that high frequency TENS contralateral to the nerve injury reduces mechanical allodynia, while low frequency reduces thermal allodynia in rats.[6][21]

- aquatics: Aquatic therapy allows activities to be performed with decreased weight bearing on the lower extremities.[6]

- mirror therapy

- desensitization[5]

- gradual weight bearing[5]

- stretching[5]

- fine motor control[5]

It is important for physical therapists to recognize that CRPS typically follows blood vessel pathways, and therefore symptoms may not always follow neural patterns. Also, due to the spread pattern, CRPS treatment should be provided bilaterally, due to the contralateral connections present between the extremities.[8]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

CRPS needs to be differentiated from the following diagnosis[7]:

- Bony or soft tissue injury

- Neuropathic pain

- Arthritis

- Infection

- Compartment syndrome

- Arterial insufficiency

- Raynaud’s Disease

- Lymphatic or venous obstruction

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

- Gardner-Diamond Syndrome

- Erythromelalgia

- Self-harm or malingering

Clinical Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Complex regional pain syndrome in adults UK guidelines for diagnosis, referral and management in primary and secondary care. Royal College of Physicians, May 2012.

Complex regional pain syndrom: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Medicine. 2013, 14: 180-229

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- More Than Meets the Eye: Clinical Reflection and Evidence-Based Practice in an Unusual Case of Adolescent Chronic Ankle Sprain

- Thoracic Spine Dysfunction in Upper Extremity Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I

Resources

[edit | edit source]

- Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association

- American Chronic Pain Association

- Mayo Clinic

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ O’CONNEL, N.E., e.a., Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome- an overview of systematic reviews (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2013. (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ RHO, R. e.a., Concise Review for Clinicians: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2002. (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ WASNER, G., e.a., Vascular abnormalities in reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS I): mechanisms and diagnostic value. Oxford University Press, 2001. (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ TRAN, Q., e.a., Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence. Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society, 2010. (level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedgoebel - ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPatho Book - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Turner-Stokes L, Goebel A. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: concise guidance. Clinical Med 2011; 11(6):596-600.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 Hooshmand H, Phillips E. Spread of complex regional pain syndrome. Vero Beach, Florida. Neurological Associates Pain Management Center.

- ↑ Cristiana Kahl Collins. Physical Therapy Management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome I in a 14-Year-Old Patient Using Strain Counterstrain: A Case Report. J Man Manip Ther. 2007; 15(1): 25–41.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 MD Guidelines, Medical DIsability Advisor. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Comorbid Conditions. http://www.mdguidelines.com/complex-regional-pain-syndrome/comorbid-conditions (accessed March 28, 2012).

- ↑ Perez R, Zuurmond W, Bezemer P, Kuik D, vanLoenen A, deLange J, et al. The treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I with free radical scavengers: a randomized controlled study. Pain 2003;102(3):297-307.

- ↑ Goldberg M, Domsky R, Scaringe D, Hirsh R, Dotson J, Sharaf I, et al. Multi-Day Low Dose Ketamine Infusion for the Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain Physician 2005;8:175-179.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cappello Z, Kasdan M, Louis D. Meta-analysis of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome type I. JHS 2012;37A:288-296.

- ↑ Medline Plus, the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health. Medical Encyclopedia: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/007184.htm (accessed 29 March 2012).

- ↑ Aurora Health Care. Health Information: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. http://www.aurorahealthcare.org/yourhealth/healthgate/getcontent.asp?URLhealthgate=%2296853.html%22 (accessed 28 March 2012).

- ↑ Simpson E, Duenas A, Holmes M, Papaloannou D, Chilcott J. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischaemic origin: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment 2009;13(17):1-179.

- ↑ Olson GL, Meyerson BA, Linderoth B. Spinal cord stimulation in adolescents with complex regional pain syndrome type I. EUR J PAIN 2008;12(1):53-59.

- ↑ Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Cervico-thoracic or lumbar sympathectomy for neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;7:1-14.

- ↑ Picarelli H, Teixeira M, deAndrade D, Myzkowski M, Luvisotto T, Yeng L, et al. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Is Efficacious as an Add-On to Pharmacological Therapy in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. J Pain 2010;11(11):1203-10.

- ↑ Arizona Pain. Stellate Ganglion Block. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=izOYrLUuNd8 [last accessed 3/29/12]

- ↑ Somers D, Clemente F. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for the Management of Neuropathic Pain: The Effects of Frequency and Electrode Position on Prevention of Allodynia in a Rat Model of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type II. Phys Ther 2006;86:698-709.

- ↑ CNN. CNN Report on Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaTlI6bfF64 [last accessed 3/28/12]