Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

[[File:Compartment Syndrome Picture Wikipedia.jpeg|right|frameless]] | [[File:Compartment Syndrome Picture Wikipedia.jpeg|right|frameless]] | ||

There are two distinct forms of compartment syndromes, acute and chronic types. | |||

# ][[Compartment Syndrome|Acute compartment syndrome]] (ACS) of the lower leg is a time-sensitive orthopedic emergency that relies heavily on precise clinical findings. Lower leg ACS is a condition in which increased pressure within a [[Muscle Cells (Myocyte)|muscle]] compartment surrounded by a closed fascial space leads to a decline in tissue perfusion and compromises motor and [[Sensation|sensory]] function. Key structures within the fascial compartment affected by increased compartment pressures include muscles, [[Neurone|nerves]] and vasculature. | |||

# Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) occurs in the setting of recurrent, reversible ischemic episodes following the cessation of activity resulting in the predictable decrease in fascial compartment pressures. Although benign, the refractory nature of CECS often results in a substantial portion of patients ultimately electing to proceed with fasciotomies<ref name=":2">Chandwani D, Varacallo M. [https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/64490/ Exertional compartment syndrome.] InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jun 3. StatPearls Publishing. Available: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/64490/<nowiki/>(accessed 29.10.2021)</ref>. | |||

Image 1: Compartment Syndrome Picture | |||

Late findings of ACS can lead to limb [[Amputations|amputation]], contractures, paralysis, [[Vital Organs|multiorgan failure]], and death. Hallmark symptoms of ACS include the 6 P’s: pain, poikilothermia, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. The definitive treatment of ACS is timely fasciotomy<ref name=":1">Pechar J, Lyons MM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4970751/ Acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg: a review.] The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2016 Apr 1;12(4):265-70. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4970751/<nowiki/>(accessed 29.10.2021)</ref>. | |||

== Etiology == | == Etiology == | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

*Drug overdose | *Drug overdose | ||

*Burns | *Burns | ||

CECS occurs after: | |||

Male patients are ten times more impacted by ACS than females, possibly due to males having larger muscle mass within a fixed compartment. Younger patients (≤ 35 years of age) are also at a greater risk to ACS due to having tighter fascia and larger muscle mass and as they are prone to injuries or accidents<ref name=":1" /> | * Repetitive and strenuous exercise. During strenuous exercise, there can be up to a 20% increase in muscle volume and weight due to increased blood flow and oedema, so pressure increases. If this pressure elevates to 30 mmHg or more, small vessels in the tissue become compressed, which leads to reduced nutrient blood flow, ischemia and pain.<ref name=":5">Oprel PP., Eversdij MG., Vlot J., Tuinebreijer WE. The Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg: A Difficult Diagnosis? Department of Surgery-Traumatology and Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 2010, 4, 115-119 </ref><sup>[</sup><ref name=":0">Bong MR., Polatsch DB., Jazrawi LM., Rokit AS. Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome, Diagnosis and Management. Hospital for Joint Diseases 2005, Volume 62, Numbers 3 & 4. </ref> The anterior compartment is affected more frequently than the lateral, deep and superficial posterior compartments.<ref name=":7">Van der Wal, W. A., et al. "The natural course of chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg." Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 23.7 (2015): 2136-2141. </ref> | ||

== Epidemiolgy == | |||

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome is typically considered a rare cause of lower extremity [[Pain Behaviours|pain]], with a reported incidence rate in active patients presenting with exercise-induced leg pain to be 33%<ref name=":2" /> | |||

Male patients are ten times more impacted by ACS than females, possibly due to males having larger muscle mass within a fixed compartment. | |||

Younger patients (≤ 35 years of age) are also at a greater risk to ACS due to having tighter fascia and larger muscle mass and as they are prone to injuries or accidents<ref name=":1" /> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

[[File:Leg compartments.jpeg|right|frameless|399x399px]] | [[File:Leg compartments.jpeg|right|frameless|399x399px]] | ||

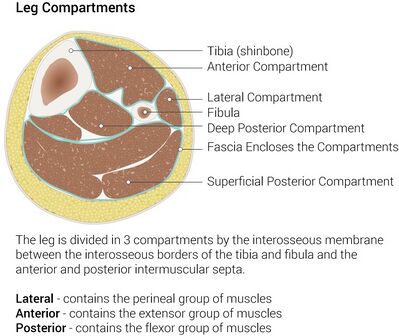

There are four compartments in the lower leg and these include the anterior, lateral, superficial posterior and deep posterior compartments. | There are four compartments in the lower leg and these include the anterior, lateral, superficial posterior and deep posterior compartments. | ||

Each compartment contains specific nerves, arteries and veins, muscles, and bony structures that with injury contribute to the unique clinical presentations in ACS. | Each compartment contains specific nerves, [[arteries]] and [[veins]], muscles, and bony structures that with injury contribute to the unique clinical presentations in ACS. | ||

Knowledge about the most important structures within these compartments is critical to efficiently assess and diagnose physiologic changes in ACS that contribute to pathologic development<ref name=":1" /> | Knowledge about the most important structures within these compartments is critical to efficiently assess and diagnose physiologic changes in ACS that contribute to pathologic development<ref name=":1" /> | ||

Patients with compartment syndrome of the lower leg suffer from long term impairment such as reduced muscular strength, reduced range of motion and pain. <ref name=":6">Frink, Michael, et al. "Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients." Injury 38.5 (2007): 607-613</ref> The most common symptoms by a compartment syndrome are:<ref name=":8" /> | Image 2: Leg compartments lower limb | ||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

Patients with compartment syndrome of the lower leg suffer from long term impairment such as reduced muscular strength, reduced [[Range of Motion|range of motion]] and pain. <ref name=":6">Frink, Michael, et al. "Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients." Injury 38.5 (2007): 607-613</ref> The most common symptoms by a compartment syndrome are:<ref name=":8" /> | |||

*Feeling of tightness | *Feeling of tightness | ||

*Swelling | *Swelling | ||

*Pain (on active flexion knee and particularly passive stretching of the muscles) | *Pain (on active flexion knee and particularly passive [[stretching]] of the muscles) | ||

*Paresthesia | *Paresthesia | ||

'''<u></u>''' | '''<u></u>''' | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

Diagnosis of ACS is based largely on physical examination and six cardinal clinical manifestations described as the six P's. | Diagnosis of ACS is based largely on physical examination and six cardinal clinical manifestations described as the six P's. | ||

* The six P's include: | * The six P's include: Pain, Poikilothermia (inability to regulate one's body temperature), Paresthesia, Paralysis, Pulselessness, and Pallor. | ||

** The earliest indicator of developing ACS is severe pain. | |||

** Pulselessness, paresthesia, and complete paralysis are found in the late stage of ACS. | |||

* Additionally, serial measurement of ICP is critical in confirming and determine progression of ACS. | * Additionally, serial measurement of ICP is critical in confirming and determine progression of ACS. | ||

* Other diagnostic considerations including the use of ancillary testing such as laboratory testing or imaging. | * Other diagnostic considerations including the use of ancillary testing such as laboratory testing or imaging. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 82: | ||

*Recording of intra-compartmental tissue pressures <ref name=":0" /><ref>Pedowitz RA, Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ, Gershuni DH: Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the leg. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:35-40. | *Recording of intra-compartmental tissue pressures <ref name=":0" /><ref>Pedowitz RA, Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ, Gershuni DH: Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the leg. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:35-40. | ||

</ref> (needle and manometer, wick catheter, slit catheter) | </ref> (needle and manometer, wick catheter, slit catheter) | ||

== Treatment == | |||

[[File:1024px-Compartment syndrome with fasciotomy procedure 01.jpeg|right|frameless]] | |||

The gold standard treatment is fasciotomy, but most of the reports on its effectiveness are in short follow-up periods.<ref name=":4">Chechik, O., G. Rachevsky, and G. Morag. "Michael Drexler, T. Frenkel Rutenberg, N. Rozen, Y. Warschawski, E. Rath, Single minimal incision fasciotomy for the treatment of chronic exertional compartment syndrome: outcomes and complications, Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery · September 2016</ref> | |||

Image 3: Compartment syndrome with fasciotomy procedure | |||

Nonoperative treatment | |||

* Whenever safe and possible, simple treatment measure in ACS include loosening ace wraps, compression dressings, splints and uni- or bivalving casts. | |||

* Elevation of extremity no higher than the level of the heart facilitates venous drainage, reduces edema and maximize tissue perfusion. | |||

* Further, avoidance of knee flexion and foot dorsiflexion will facilitate uncompromised circulation throughout a limb and limit increases in ICP in the deep posterior compartment respectively<ref name=":1" /> | |||

CECS is typically managed nonoperatively for a one- to three-month duration, and surgical management may often be delayed and/or electively performed after having a discussion with the patient (or athlete) regarding the ideal timing given the athletes current sport-specific requirements. | |||

Conservative management consists of rest, activity modification, stretching, orthotics, and physical therapy. Nonoperative modalities include, but are not limited to: | |||

* NSAIDs | |||

* Botulinum toxin injections<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* Gait training | |||

* | |||

== Physical Therapy Management == | == Physical Therapy Management == | ||

The only nonoperative treatment that is certain to alleviate the pain of CECS is the cessation of causative activities. | The only nonoperative treatment that is certain to alleviate the pain of CECS is the cessation of causative activities. | ||

* Normal physical activities should be modified, pain allowing. | |||

* Cycling may be substituted for running in patients who wish to maintain their cardiorespiratory fitness, as it is associated with a lower risk of compartment pressure elevation. | |||

* Massage therapy may provide some benefit to patients with mild symptoms or to those who decline surgical intervention. | |||

< | Overall, however, nonoperative treatment has been generally unsuccessful <ref name=":0" /> and symptoms will not disappear without treatment. | ||

'''Physical Therapy in CECS ''' | |||

'''Pre-surgical therapy''' | Conservative therapy has been attempted for CECS, but it is generally unsuccessful. Symptoms typically recur once the patient returns to exercise. Discontinuing participation in sports is an option, but it is a choice that most athletes refuse. <ref name=":12">Gregory A Rowdon, MD; Chief Editor: Craig C Young, MD et al Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome Treatment & Management Updated: Oct 08, 2015. </ref><br>'''Pre-surgical therapy''' | ||

Pre-surgical therapy in CECS includes reduction of activity, with encouragement of cross-training and muscle stretching before initiating exercise | Pre-surgical therapy in CECS includes reduction of activity, with encouragement of cross-training and muscle stretching before initiating exercise. Other preoperative measures are rest, shoe modification, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications ([[NSAID Gastropathy|NSAID]]<nowiki/>s) to reduce inflammation.<ref name=":12" /> | ||

'''Post-surgical therapy''' | '''Post-surgical therapy''' | ||

Post-surgical therapy for CECS includes assisted weight bearing with some variation, depending on surgical technique. Early mobilisation is recommended as soon as possible to minimise scarring, which can lead to adhesions and a recurrence of the syndrome. | Post-surgical therapy for CECS includes assisted [[weight bearing]] with some variation, depending on surgical technique. Early mobilisation is recommended as soon as possible to minimise scarring, which can lead to adhesions and a recurrence of the syndrome. | ||

Activity can be upgraded to stationary cycling and swimming after healing of the surgical wounds. Isokinetic muscle strengthening exercises can begin at 3-4 weeks. Running is integrated into the activity program at 3-6 weeks. Full activity is introduced at approximately 6-12 weeks, with a focus on speed and agility.<ref name=":12" /> The following are recommendations for a full recovery and to avoid recurrence; | Activity can be upgraded to stationary cycling and swimming after healing of the surgical wounds. Isokinetic muscle strengthening exercises can begin at 3-4 weeks. Running is integrated into the activity program at 3-6 weeks. Full activity is introduced at approximately 6-12 weeks, with a focus on speed and agility.<ref name=":12" /> The following are recommendations for a full recovery and to avoid recurrence; | ||

Latest revision as of 06:06, 29 October 2021

Original Editors - Geoffrey De Vos

Top Contributors - Delmoitie Giovanni, Scott Cornish, Geoffrey De Vos, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Glenn-Gerlo, Bettina Vansintjan, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, Karen Wilson and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There are two distinct forms of compartment syndromes, acute and chronic types.

- ]Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) of the lower leg is a time-sensitive orthopedic emergency that relies heavily on precise clinical findings. Lower leg ACS is a condition in which increased pressure within a muscle compartment surrounded by a closed fascial space leads to a decline in tissue perfusion and compromises motor and sensory function. Key structures within the fascial compartment affected by increased compartment pressures include muscles, nerves and vasculature.

- Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) occurs in the setting of recurrent, reversible ischemic episodes following the cessation of activity resulting in the predictable decrease in fascial compartment pressures. Although benign, the refractory nature of CECS often results in a substantial portion of patients ultimately electing to proceed with fasciotomies[1].

Image 1: Compartment Syndrome Picture

Late findings of ACS can lead to limb amputation, contractures, paralysis, multiorgan failure, and death. Hallmark symptoms of ACS include the 6 P’s: pain, poikilothermia, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. The definitive treatment of ACS is timely fasciotomy[2].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Any condition that results in an increase of pressure in a compartment can lead to the development of acute (ACS) or chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS).

- Fracture of the tibial diaphysis

- Soft-tissue injury

- Intensive muscle use

- Everyday extreme exercise activities

- Arterial injury

- Drug overdose

- Burns

CECS occurs after:

- Repetitive and strenuous exercise. During strenuous exercise, there can be up to a 20% increase in muscle volume and weight due to increased blood flow and oedema, so pressure increases. If this pressure elevates to 30 mmHg or more, small vessels in the tissue become compressed, which leads to reduced nutrient blood flow, ischemia and pain.[5][[6] The anterior compartment is affected more frequently than the lateral, deep and superficial posterior compartments.[7]

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome is typically considered a rare cause of lower extremity pain, with a reported incidence rate in active patients presenting with exercise-induced leg pain to be 33%[1]

Male patients are ten times more impacted by ACS than females, possibly due to males having larger muscle mass within a fixed compartment.

Younger patients (≤ 35 years of age) are also at a greater risk to ACS due to having tighter fascia and larger muscle mass and as they are prone to injuries or accidents[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

There are four compartments in the lower leg and these include the anterior, lateral, superficial posterior and deep posterior compartments.

Each compartment contains specific nerves, arteries and veins, muscles, and bony structures that with injury contribute to the unique clinical presentations in ACS.

Knowledge about the most important structures within these compartments is critical to efficiently assess and diagnose physiologic changes in ACS that contribute to pathologic development[2]

Image 2: Leg compartments lower limb

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with compartment syndrome of the lower leg suffer from long term impairment such as reduced muscular strength, reduced range of motion and pain. [8] The most common symptoms by a compartment syndrome are:[4]

- Feeling of tightness

- Swelling

- Pain (on active flexion knee and particularly passive stretching of the muscles)

- Paresthesia

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of ACS is based largely on physical examination and six cardinal clinical manifestations described as the six P's.

- The six P's include: Pain, Poikilothermia (inability to regulate one's body temperature), Paresthesia, Paralysis, Pulselessness, and Pallor.

- The earliest indicator of developing ACS is severe pain.

- Pulselessness, paresthesia, and complete paralysis are found in the late stage of ACS.

- Additionally, serial measurement of ICP is critical in confirming and determine progression of ACS.

- Other diagnostic considerations including the use of ancillary testing such as laboratory testing or imaging.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Acute compartment syndrome

- On assessment, the primary finding is swelling of the affected extremity

- The inability to actively move flexors and extensors of the foot is an important indicator [5]

- Signs such as progression of pain

- Pain with passive stretching of the affected muscles

- Often a disturbance sensation in the web space between the first and second toes is found as a consequence of compression or ischemia of the deep peroneal nerve. This nerve is found in the anterior compartment. Reduced sensation represents a late sign of ACS

- Absence of arterial pulse is more often a sign of arterial injury than a late sign of ACS

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

- Pain starts within first 30 minutes of exercise and can radiate to ankle/foot [6]

- Pain ceases when activity is stopped

- Daily activities usually not provocative

- On assessment, the primary finding is swelling of the affected extremity

- The inability to actively move flexors and extensors of the foot is an important indicator

- Signs such as progression of pain

- Recording of intra-compartmental tissue pressures [6][9] (needle and manometer, wick catheter, slit catheter)

Treatment[edit | edit source]

The gold standard treatment is fasciotomy, but most of the reports on its effectiveness are in short follow-up periods.[10]

Image 3: Compartment syndrome with fasciotomy procedure

Nonoperative treatment

- Whenever safe and possible, simple treatment measure in ACS include loosening ace wraps, compression dressings, splints and uni- or bivalving casts.

- Elevation of extremity no higher than the level of the heart facilitates venous drainage, reduces edema and maximize tissue perfusion.

- Further, avoidance of knee flexion and foot dorsiflexion will facilitate uncompromised circulation throughout a limb and limit increases in ICP in the deep posterior compartment respectively[2]

CECS is typically managed nonoperatively for a one- to three-month duration, and surgical management may often be delayed and/or electively performed after having a discussion with the patient (or athlete) regarding the ideal timing given the athletes current sport-specific requirements.

Conservative management consists of rest, activity modification, stretching, orthotics, and physical therapy. Nonoperative modalities include, but are not limited to:

- NSAIDs

- Botulinum toxin injections[2]

- Gait training

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The only nonoperative treatment that is certain to alleviate the pain of CECS is the cessation of causative activities.

- Normal physical activities should be modified, pain allowing.

- Cycling may be substituted for running in patients who wish to maintain their cardiorespiratory fitness, as it is associated with a lower risk of compartment pressure elevation.

- Massage therapy may provide some benefit to patients with mild symptoms or to those who decline surgical intervention.

Overall, however, nonoperative treatment has been generally unsuccessful [6] and symptoms will not disappear without treatment.

Physical Therapy in CECS

Conservative therapy has been attempted for CECS, but it is generally unsuccessful. Symptoms typically recur once the patient returns to exercise. Discontinuing participation in sports is an option, but it is a choice that most athletes refuse. [11]

Pre-surgical therapy

Pre-surgical therapy in CECS includes reduction of activity, with encouragement of cross-training and muscle stretching before initiating exercise. Other preoperative measures are rest, shoe modification, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation.[11]

Post-surgical therapy

Post-surgical therapy for CECS includes assisted weight bearing with some variation, depending on surgical technique. Early mobilisation is recommended as soon as possible to minimise scarring, which can lead to adhesions and a recurrence of the syndrome.

Activity can be upgraded to stationary cycling and swimming after healing of the surgical wounds. Isokinetic muscle strengthening exercises can begin at 3-4 weeks. Running is integrated into the activity program at 3-6 weeks. Full activity is introduced at approximately 6-12 weeks, with a focus on speed and agility.[11] The following are recommendations for a full recovery and to avoid recurrence;

- Wearing more appropriate footwear to the terrain

- Choosing more appropriate surfaces and terrain for exercise

- Pacing your activities

- Avoiding certain activities altogether

- Mastering strategies for recovery and maintenance of good health (e.g, appropriate rest between sessions)

- Modifying the workplace to lower the risk of injury

Postoperative physical therapy is essential for a successful recovery. depending on the nature of the procedure, expected timelines for healing and progress made during rehabilitation. Treatment incorporates strategies to restore range of motion, mobility, strength and function.[12]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

- Acute Compartment Syndrome (ACS) of the lower leg is a time sensitive limb threatening surgical emergency.

- Late findings of ACS can lead to limb amputation, contractures, paralysis, multi-organ failure and death.

- Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, assessment of the six P's (pain, poikilothermia, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness and paralysis) and intracompartmental pressure (ICP).

- ICP measurement above 30mmHg is considered critical and treatment with emergent surgical decompression should be considered.

- The gold standard of acute compartment treatment is full fasciotomy[2].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chandwani D, Varacallo M. Exertional compartment syndrome. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jun 3. StatPearls Publishing. Available: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/64490/(accessed 29.10.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Pechar J, Lyons MM. Acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg: a review. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2016 Apr 1;12(4):265-70. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4970751/(accessed 29.10.2021)

- ↑ McQueen, M. M., and P. Gaston. "Acute compartment syndrome." Bone & Joint Journal 82.2 (2000): 200-203.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Abraham TR. Acute Compartment Syndrome. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. (2016)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Oprel PP., Eversdij MG., Vlot J., Tuinebreijer WE. The Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg: A Difficult Diagnosis? Department of Surgery-Traumatology and Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 2010, 4, 115-119

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Bong MR., Polatsch DB., Jazrawi LM., Rokit AS. Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome, Diagnosis and Management. Hospital for Joint Diseases 2005, Volume 62, Numbers 3 & 4.

- ↑ Van der Wal, W. A., et al. "The natural course of chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg." Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 23.7 (2015): 2136-2141.

- ↑ Frink, Michael, et al. "Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients." Injury 38.5 (2007): 607-613

- ↑ Pedowitz RA, Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ, Gershuni DH: Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the leg. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:35-40.

- ↑ Chechik, O., G. Rachevsky, and G. Morag. "Michael Drexler, T. Frenkel Rutenberg, N. Rozen, Y. Warschawski, E. Rath, Single minimal incision fasciotomy for the treatment of chronic exertional compartment syndrome: outcomes and complications, Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery · September 2016

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gregory A Rowdon, MD; Chief Editor: Craig C Young, MD et al Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome Treatment & Management Updated: Oct 08, 2015.

- ↑ Val Irion, Robert A. Magnussen, Timothy L. Miller , Christopher C. Kaeding “Return to activity following fasciotomy for chronic exertional compartment syndrome” Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol , Volume 24, Issue 7, pp 1223–1228.