Cervical Radiculopathy

Original Editor - Stéphanie Dartevelle

Top Contributors - Scott Buxton, Admin, Jasper Vermeersch, Stéphanie Dartevelle, Rachael Lowe, Garima Gedamkar, Kim Jackson, Scott Cornish, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Thomas Rodeghero, Jesse Demeester, Laura Ritchie, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Evan Thomas, Stijn De Coninck, Venugopal Pawar, Fasuba Ayobami, Maxime Tuerlinckx, Candace Goh, Rucha Gadgil, Wendy Walker, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Johnathan Fahrner, Khloud Shreif, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Jelle Van Hemelryck

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

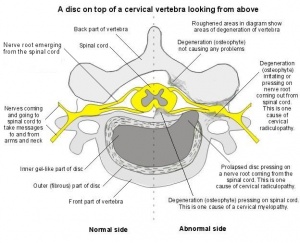

"Cervical radiculopathy is a disease process marked by nerve compression from herniated disk material or arthritic bone spurs. This impingement typically produces neck and radiating arm pain or numbness, sensory deficits, or motor dysfunction in the neck and upper extremities."[1]

Cervical radiculopathy occurs with pathologies that causes symptoms on the nerve roots. [2] Those can be compression, irritation, traction, and a lesion on the nerve root caused by either a herniated disc, foraminal narrowing or degenerative spondylitic change (Osteoarthritic changed or degeneration) leading to stenosis of the intervertebral foramen[2] [3].

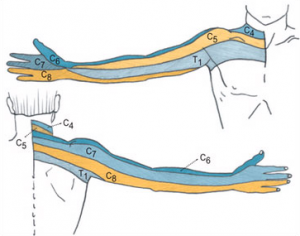

We have 8 cervical nerve roots, for 7 cervical vertebrae and this may seem confusing at first. However a nerve root comes out of the spinal column between C7 and T1, hence the name C8 as T1 already exists [2].

Most of the time cervical radiculopathy appears unilaterally, however it is possible for bilateral symptoms to be present if severe bony spurs are present at one level, impinging/irritating the nerve root on both sides. If peripheral radiation of pain, weakness or pins and needle are present, the location of the pain will follow back to the concerned afected nerve root [2].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Cervical radiculopathy is defined as a disorder affecting a spinal nerve root in the Cervical Spine, therefore a knowledge of the brachial plexus is crucial to understanding the impact of nerve root impingement or damge has on the body.

| [4] |

Epidemiology / Etiology

[edit | edit source]

Simply defined cervical radiculopathy is a dysfunction of a nerve root in the cervical spine, as this is such a broad disorder with several mechanisms of pathology people of any age can be affected[5], with peak prominence between the ages of 40-50[6][7][8] with a reported prevelance of 83 people per 100,000 people[2]

The two main mechanisms of the nerve root irritation or impingement are[9]:

- Spondylosis leading to stenosis - More common in older patients

- Disc Herniation - More common in younger patients

This rule is not correct 100% of the time but it is a good basis to go on for a logical reason: As you age, disc height decreases and there is less material within the intervertebral disc itself making a prolapse less likely and making it harder for a prolapse to impinge a nerve root.

Just think: There is more material to prolapse from a disc of a younger person!

Of all of the potential nerve roots to be impinged upon the C7 (46.3%) and C6 (16.7%) roots are most commonly affected, the potential explanation for this is that the foramina are largest in the upper cervical region and progressively decrease in size as you descend making nerves more susceptable[10]. The order of most commonly affected nerve roots goes:

C7 (46%) --> C6 (18%) --> C5 (6%) --> C8 (6%)[10]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typical symptoms of cervical radiculopathy are: radiating arm pain corresponding to the dermatomes (no always present), neck pain, parasthesia, muscle weakness in myotome, reflex impairment/loss, headaches, scapular pain and sensory and motor dysfunction in upper extremities and neck. [2] [8] [3] [11] [12]

If a nerve root is compressed it can cause a combination of factors: inflammatory mediators, changes in vascular response and intraneural edema which cause radicular pain. Absence of radiating pain doesn’t exclude nerve root compression. The same appears with sensory and motor dysfunction that might be present without significant pain. [2]

Symptoms are generally amplified when an extension or rotation of the neck takes place, because the neural foramen becomes smaller or the (dysfunctional) neural tissue is mechanically charged. [2] This often induce a decrease in cervical spine range of motion (ROM), which can result in a decrease in muscle length of the cervical spine musculature (upper trapezius, scalenes, levator scapula).

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

When you want to diagnose Cervical radiculopathy (CR), you have to consider several other conditions that sometimes have the same symptoms of CR, such as shoulder pathology, peripheral nerve disorders, thoracic outlet syndrome, brachial plexus pathology, systemic disease, Cervical myelopathy, Ligamentous Instability, Vertebral Artery Insufficiency, Herniated nucleous pulposus and spinal tumors. Parsonage-Turner syndrome is also a condition that can have the same symptoms. This condition is not well known amongst physical therapists. [13]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The most common diagnostic method has been imaging studies (radiograph and MRI) to check the presence of possible compression and electrophysiologic studies (EMG) to examine nerve conduction velocity.[14] [2] [8] In 2003, Dr. Robert Wainner and colleagues examined the accuracy of the clinical examination and developed a clinical prediction rule to aid in the diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. Their research demonstrated that these 4 clinical tests, when combined, hold high diagnostic accuracy compared to EMG studies: Positive tests for Spurling-A, Upper limb tension-A, distraction test and cervical rotation of the involved side less than 60 degrees (see resources for more information regarding these tests). When all 4 of these clinical features are present, the post-test probablity of cervical radiculopathy is 90%, if only three of the four test are positive the probability decrease to 65%.[15] [3] [8]

We also make a difference between acute and chronical. Most of the time a radiating pain caused by a disk herniation is acute, while bilateral axial neck and radiating arm pain caused by cervical spondylosis is chronical. [2]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures are an essential tool to assess whether or not you are having a positive. negative or static effect on a patients' condition. Cervical Radiculopathy is no different. There are a lot of outcome measures in existance and it is important to know if the tool you are using is measuring what you want to measure (Specificity) and how good it is correctly identifying a pattern (Sensitivity)[16].

FABQ NDI Neck Pain and Disability Scale

Examination[edit | edit source]

There is a group of clinical exam tests that all together have a 90% probability to diagnose cervical radiculopathy. These tests are the upper limb tension test, ipsilateral cervical rotation less than 60 degrees, neck distraction test and Spurling test. [17]

On the other hand another article concluded that Spurling, neck distraction, Valsalva and upper limb tension tests are most useful in establishing a diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy in patients without neurological deficits. While a negative ULTT test might be used to rule it out. [18]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

There are several intervention strategies for managing cervical radiculopathy with physical therapy and surgical interventions being the most common. Long-term benefits of surgical interventions are questionable with reported numbers of 25% of people continuing to experience pain and disability at 12 month follow-ups[19]. There is a significant amount of evidence available to support the use of physical therapy interventions for patients with cervical radiculopathy, and the benefit of physical therapy and manual techniques in general for patients with neck pain with or without radicular symptoms (see key evidence for a list of references).

The nonoperative treatment includes a period (+/- one week, not more) of immobilisation with a cervical collar to decrease the compression on the nerve root; cervical traction; medication to reduce the pain; physical therapy and manipulation including massage, stretching, exercices to improve range of motion and eventually ice, heat and electrical stimulation. They must be used together and not separately to show improvement. But all these elements of the treatment need further studies to prove more effectiveness. [2]

Physiotherapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Regarding physical therapy interventions, in 2007 Joshua Cleland and colleagues examined the predictors of positive short-term outcomes in people with a clinical diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. The following clinical features were found to be most predictive of a positive short-term outcome:

- Age <54

- Dominant arm not affected

- Looking down does not worsen symptoms

- Treatment involves manual therapy, cervical traction, and deep neck flexor strengthening for at least 50% of visits

If 3 of these features are present, the probability of success is 85%, and increases to 90% if all 4 are present[20]

Although a definitive treatment progression for treating CR has not been developed a general consensus exists within the literature that using manual therapy techniques in conjunction with therapeutic exercise is effective in regard to increasing function, as well as AROM, while decreasing levels of pain and disability[21].

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis is important for any condition but due to the close proximity of the cervical spine and structures such as the vertebral arteries it is crucial that you, during the initial assessment of a patient, that you rule out any conditions which can cause severe damage to the patients blood supply to the brain especially during any manual therapy.

- Spinal Tumor

- Systemic diseases known to cause peripheral neuropathies

- Cervical myelopathy

- Ligamentous Instability

- Vertebral Artery Insufficiency (VBI)

- Herniated nucleous pulposos (HNP)

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

The following are key evidence pieces for physical therapy interventions as they relate to both cervical radiculopathy and neck pain in general:

Manual therapy compared to 'usual' physical therapy and general practitioner care[22]

Clinical Practice Guidelines[23]

Classification System for Neck Pain[24]

Proposal of Treatment-Based Classification System[25]

Prognostic factors for neck pain in the general population[26]

Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation for patients with neck pain[27]

Clinical prediction rule for thoracic manipulation in patients with neck pain[28]

Related Pages

[edit | edit source]

CPR for cervical radiculopathy

CPR for traction for neck pain

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Neck Pain

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1pk-02YRTTMMVRCbL7mlDo1kpFvw423q5b0YiejfNFm06UlM9q|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Eubanks J. Cervical Radiculopathy: Nonoperative Management of Neck Pain and Radicular Symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2010 Jan 1;81(1):33-40.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Eubanks, JD.Cervical Radiculopathy:Nonoperative Management of Neck Pain and Radicular Symptoms.American Family Physician 2010;81,33-40

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kenneth A. Olson. Manual physical therapy of the spine.Saunders Elsevier 2009.p 253, 257, 258

- ↑ Anatomy Zone. Brachial Plexus - Branches - 3D Anatomy Tutorial. Available from:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VdiFNYdIo1ofeature=c4-overview-list=PLmGQgRI4QyEDCSPyYurmzj_zatY5BWz_r

- ↑ Marc J. Levine, Todd J. Albert, Michael D. Smith.Cervical Radiculopathy: Diagnosis and Nonoperative Management.Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 1996;4:305-316

- ↑ Ellenberg M, Honet J, Treanor W. Cervical Radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994; 75:342-352.

- ↑ Radhaknshnank et al. Epidemiology of Cervical Radiculopathy. A Population Based Study. Brain. 1994: 117; 325-335

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Young IA,Michener LA,Cleland JA,Aguilera AJ,Snyder AR.Manual therapy, exercise, and traction for patients with cervical radiculopathy: a randomize clinical trial.Physical Therapy 2009;89:632-642 (B)

- ↑ Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon M, et al. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy: A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain 1994; 117:325-335.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bogduk N. Twomey CT. Clinically Relevant Anatomy for the Lumbar Spine. 2ed. Edinburgh UK: Churchill Livingston. 1991

- ↑ Kenneth W. Lindsay, Ian Bone.Neurology and neurosurgery illustrated.4th ed. Churchill Livingstone.p408

- ↑ Kuijper B, Tans JT, Beelen A, Nollet F, de Visser M.Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy : randomised trial.BMJ 2009;p1-7

- ↑ C: R. Erhard et al. Cervical Radiculopathy or Parsonage-Turner Syndrome: Differential Diagnosis of a Patient With Neck and Upper Extremity Symptoms. JOSPT. OCTOBER 2005fckLRVolume 35, No. 10

- ↑ Partanen J, Partanen K, Oikarinen H, et al. Preoperative electroneuromyography and myelography in cervical root compression. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991; 31:21-26.

- ↑ Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2003;28(1):52-62.

- ↑ Lalkhen A. McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain (2008) 8 (6): 221-223.

- ↑ C: Wainner et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine 2003 Jan 1. 28(1):52-62.

- ↑ A1: Sidney M. Rubinstein et al. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. European Spine Journal. Volume 16, Number 3, 307-319

- ↑ Heckmann J, Lang J, Zobelein I, et al. Herniated cervical intervertebral discs with radiculopathy: an outcome study of conservatively or surgically treated patients. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:396-401.

- ↑ Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Whitman JM, et al. Predictors of short-term outcomes in people with a clinical diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. Phys Ther. 2007;87(12):1619-1632.

- ↑ Boyles, Robert; Toy, Patrick; Mellon, James; Hayes, Margaret; Hammer, Bradley.Effectiveness of manual physical therapy in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy 19 (2011) 135-142.

- ↑ Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HC, et al. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by a general practitioner for patients with neck pain. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(10):713-722.

- ↑ Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, et al. Neck Pain: Clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Assoction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):A1-A34.

- ↑ Childs JD, Fritz JM, Piva SR, et al. Proposal of a Classification System for Patients with Neck Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(11):686-700.

- ↑ Fritz JM &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Brennan GP. Preliminary Examination of a Proposed Treatment-Based Classification System for Patients Receiving Physical Therapy Interventions for Neck Pain. Phys Ther. 2007;87(5):513-524.

- ↑ Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, et al. Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in the General Population. Spine. 2008;33(4S):S75-S82.

- ↑ Cleland JA, Childs JD, McRae M, et al. Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation in patients with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Man Ther. 2005;10:127-135.

- ↑ Cleland JA, Childs JD, Fritz JM, et al. Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Guiding Treatment of a Subgroup of Patients with Neck Pain: Use of Thoracic Spine Manipulation, Exercise, and Patient Education. Phys Ther. 2007;87(1):9-23.