Cauda Equina Syndrome

Original Editor - Laurie Fiegle and Tabitha Korona

Top Contributors - Laura Finucane, Tabitha Korona, Scott Buxton, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Thibaut Seys, Laurie Fiegle, Jolien Wauters, Kim Jackson, Evan Thomas, Rachael Lowe, Margo De Mesmaeker, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Claire Knott, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, Kai A. Sigel, 127.0.0.1, Karen Wilson, Tony Lowe, Candace Goh, Shaimaa Eldib, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Saud Alghamdi and Garima Gedamkar

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases:

- PubMed

- PEDro

- Public library

- Google Scholar

- Web of knowledge

Keywords:

- Cauda equina

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

Definition[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome is a serious neurological condition affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord. It is due to a nerve compression that an acute loss of function of the lumbar plexus occurs which stops the sensation and movement[1]. The syndrome is characterized by dull pain in the lower back and upper buttocks and a lack of feeling in the buttocks, genitalia and thigh, together with the disturbance of bowel and bladder function[2].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

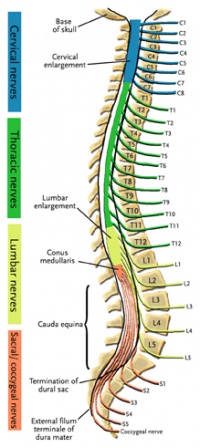

The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord. The spinal cord allows transmission of signals to and from the brain to allow for movement, sensation, and visceral function. Nerves exiting the spinal cord are divided into sections based on their location of exit; for example, cervical nerves exit the cervical spine and thoracic nerves exit the thoracic spine. The conus medullaris is the distal end of the spinal cord and is usually located at the L1-L2 vertebral level[3].

Nerve roots continue to down the vertebral column after the conus medullaris and are referred to as the cauda equina. The cauda equina includes nerves from lumbar, sacral and coccygeal origins. Being a bundle of nerves, the cauda equina is named for its resemblance to a horse's tail.

The spinal cord extends from the medulla oblongata to the level of T12-L1 where it terminates as the conus medullaris[4]. The cauda equina consists of nerve roots distal to the conus medullaris. These have both a dorsal and ventral root. Each root has specific function. The ventral root provides motor fibers for the efferent pathway and sympathetic fibers[4][5]. The dorsal root is composed of afferent fibers for the transmission of sensation. Orientation within the cauda equina is unique and specific[5]. The lower lumbar and all the sacral nerves come together in the cauda equina region. The functions of those nerves are[4]:

- Sensory innervation to the saddle area

- Voluntary control of the external anal and urinary sphincters

- Sensory and motor fibers to the lower limbs.

Epidemiology/Etiology

[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome can be caused by a number of etiologies but the most common relate to compression of the cauda equina such as a herniated lumbosacral disc, spinal stenosis, and spinal neoplasm. Non-compressive causes include ishemia, infection, and inflammatory conditions.

Ruptured disc, tumor, or fracture can also lead to Cauda equina syndrome.

CES is rare, both atraumatically as well as traumatically. Males and females are equally affected, and it can occur at any age but primarily in adults. The incidence of CES is variable, depending on the etiology of the syndrome. The prevalence among the general population has been estimated between 1:100 000 and 1:33 000. The most common cause of CES is herniation of a lumbar intervertebral disc[3]. It is reported by approximately 1% to 10% of patients with herniated lumbar disks. The prevalence among patients with low back pain is approximately four in 10 000[6].

Many structures, pathologies and iatrogenic processes are attributed to damaging the cauda equina, including infections such as meningitis, rare causes such as abdominal aortic dissection, and complications after surgery, anesthetic procedures, spinal manipulation or epidural injections[7]. Arslanoglu and Aygun recently reported a case in which ankylosing spondylitis eroded the posterior elements and traction on the lumbar nerve roots and led to CES. Mohit and colleagues described how an inferior vena cava thrombosis led to CES in a 16-year-old patient and how an inferior vena cava thrombectomy was required to relieve symptoms. The literature includes fewer than 20 reports of cases in which sarcoidosis caused CES, with the most recent report, by Kaiboriboon and colleagues[5].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

| [8] |

Since the cauda equina nerve roots supply most of the lower extremities (including the pelvic region) sensory and motor innervations, cauda equina syndrome results in multiple motor and sensory signs. The most common signs and symptoms include bilateral sciatica, saddle region anesthesia, loss of bowel and bladder control, bilateral foot weakness, quadriceps weakness, and severe back pain. Other signs and symptoms include decreased sensation between the legs, buttocks, or feet[9].

Differential Diagnoses[edit | edit source]

- Conus medullaris syndrome * Herniated Nucleus Pulposis * Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Lumbar vertebrae fracture

- Mechanical back pain

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Spinal cord compression

- Spinal tumor

- Sacral fractures[5]

- Abscesses[5]

- Lymphoma

- Central or centerolateral disk prolapsed[7]

- Space-occupying lesions that compress nerve roots have been described as causes of CES.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

If cauda equina syndrome is expected, medical referral is a necessity to decrease the possibility of permanent damage. Diagnostic procedures used to confirm cauda equina syndrome may include an MRI or myelogram[10]. For diagnosis of cauda equine syndrome, one or more of the following must be present[7][2]

- Bladder and/or bowel dysfunction - Reduced sensation in saddle area - Sexual dysfunction

+ Possible neurological deficit in the lower limb (motor/sensory loss, reflex change)

Outcomes Measures[edit | edit source]

Based on the SF-36, ODI, and Low Back Outcome Scores, patients who have had CES do not return to a normal status[11].

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

| [12] |

Once CES is diagnosed, emergent surgical decompression is recommended to avoid potential permanent neurological damage[6].

The emergent surgical decompression must take place as soon as possible in order to reduce or eliminate pressure on the nerve. It is recommended to perform the decompression within 24-48 hours after the appearance of the first symptoms of compression so that there is a maximum potential for improvement of sensory and motor deficits as well as bladder and bowel functioning[13].

The role of surgery is to relieve pressure from the nerves in the cauda equina region and to remove the offending elements[13].

Surgical strategy is usually focused on the underlying causes. Generally, spine posterior decompression is often adequate - unless there is a lesion such as vertebrae destruction, neoplasm or large abscess in the anterior spine. Multiple surgical approaches of decompression are recommended such as discectomy, microdiscectomy, microscopic decompression, fenestrations, laminectomy, hemisemilaminotomy, distraction laminoplasty, multilevel laminectomies, neurolysis of CE, and intradural exploration of the nerve roots[6].

The surgical decompression takes away the cause of pain but most individuals still have complaints afterwards:

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction

- Muscle weakness or paralysis in lower extremities - Walking disorders[7]

Most recovery takes place in the first year after the operation; however, there can be recovery up to the third year post-operation. After this time period, recovery is very minimal[14].

Physical Therapy management

[edit | edit source]

The ultimate goals of physical management are to ensure maximum neurological recovery and independence, a pain-free and flexible spine, maintenance of mobility and strength in lower limbs, of core strength, improvement of standing and walking function, improvement of bladder, bowel and sexual function, improvement of endurance and safe functioning of the various systems of the body with minimal or no inconvenience to patients and prevention or minimization of complications. [11](Level of evidence 1A) It is equally important for patients to regain assertiveness, take control of their own lives, and return to activities of their choice. The importance of on-going support to maintain health and independence following discharge should be strongly emphasized. [14, 15](Level of evidence 3A & 1A)

Locomotion training as a therapeutic exercise was initially recognized in spinal cord injury patients, beginning with Body-weight Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT) and Knee Ankle Foot Orthosis (KAFOs) personalized in soft-cast for the stabilization of the limbs. They have experienced Patterned Electrical Stimulation (PES) assisted isometric exercise to prevent limb muscle atrophy. It is known that PES-assisted isometric exercise reduces the degree of lower limb muscle atrophy in individuals with recent motor complete spinal cord injury, but not to the same extent as a comparable program of FES assisted exercise. [16] (Level of evidence 1B)

The principles of using electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves or nerve roots for restoring useful bladder, bowel, and sexual function after damage or disease of the central nervous system are described. Activation of somatic or parasympathetic efferent nerves can produce contraction of striated or smooth muscle in the bladder, rectum, and sphincters. Activation of afferent nerves can produce reflex activation of somatic muscle and reflex inhibition or activation of smooth muscle in these organs. In clinical practice these techniques have been used to produce effective emptying of the bladder and bowel in patients with spinal cord injury and to improve continence of urine and feces. [17] (Level of evidence 1A)

The use of manual therapy in conjunction with exercise is of potential benefit for patients suffering from low back pain. Utilization of manual therapy in a management program is associated with improvements in pain and disability. It is noteworthy to mention, however, that the manual therapy used in these studies was not of uniform technique nor applied only to one region. The techniques used in these studies were varied, and included both thrust and non-thrust manipulation/mobilization. Successful results were reported with techniques described as follows: flexion distraction manipulations, sidelying lumbar rotation thrust, posterior-to-anterior mobilizations, sidelying translatoric side bending manipulations, thoracic thrusts and neural mobilizations. [18](Level of evidence 1A)

Individualized exercises often include components of unweighted walking or cycling, spinal mobility and lumbar flexion exercises, hip mobility exercises, hip strengthening, and core strengthening. [18](Level of evidence 1A)

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome is rare and is estimated to account for fewer than 1 in 2000 of patients with severe low back pain[11] (Level of evidence 1A)

The annual incidence rate of cauda equina lesions has been estimated at 3.4 per million and the period prevalence at 8.9 per 100,000 [19]

It’s accounting for a reported incidence of 1-5% of spinal pathology in the literature.[20] (Level of evidence 2B)

Presentations[edit | edit source]

| [15] | [16] |

Resources

[edit | edit source]

For more information regarding the emergency medical treatment of cauda equina syndrome please see the article entitled "Orthopedic pitfalls:cauda equina syndrome." [21]

Case Studies

[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jun W. et al. Cauda equina syndrome caused by a migrated bullet in dural sac. Turk Neurosurg 2010 Oct;20(4):566-9. [1C]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Shi J. et al. Clinical classification of cauda equina syndrome for proper treatment. Acta orthop 2010 Jun;81(3):391-5. [1B] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Shi" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Boek: Dutton, M. (2008). Orthopaedic: Examination, evaluation, and intervention (2nd ed.). New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 John McNamee, Peter Flynn, [...], and Barry Kelly, Imaging in Cauda Equina Syndrome – A Pictorial Review, The ulster Medical Journal, Januarie 1, 2013. Pictorial review. [5]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Alex Gitelman, MD, Shuriz Hishmeh, MD, Brian N. Morelli, Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review, The American Journal of Orthopedics®, 2008. [3A]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 MA Bin, WU Hong, JIA Lian-shun, YUAN Wen, SHI Guo-dong and SHI Jian-gang, Cauda equina syndrome: a review of clinical progress, Chinese Medical Journal, 2009 [1A]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Stuart Fraser, Lisa Roberts, Eve Murphy, Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Literature Review of Its Definition and Clinical Presentation, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Volume 90, Issue 11, Pages 1964-1968, November 2009 [1A]

- ↑ High Impact Graphics. Anatomy and Function of Cauda Equina. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IcvkQloIc_g [last accessed 20/04/14]

- ↑ Shapiro S. Medical Realities of Cauda Equina Syndrome Secondary to Lumbar Disc Herniation. SPINE 2000;25:3, 348-52

- ↑ Ogilvie J. Complications in Spondylolisthesis Surgery. SPINE 2005;30:65 S97-S101

- ↑ McCarthy MJ, Aylott CE, Grevitt MP, Hegarty J., Cauda equina syndrome: factors affecting long-term functional and sphincteric outcome, 2007 [2B]

- ↑ Robert Hacker. Microsurgery for disc herniation with Cauda Equina Syndrome. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbcXBk3sqrU [last accessed 20/04/14]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 A. Gardner, E. Gardner and T. Morley, Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position, Eur Spine J. 2011 May; 20(5): 690–697. [1A]

- ↑ Wagih E.M., Management of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries: current standard of care revisited, ACNR, Volume 10 Nr.1, March/April 2010 [3A]

- ↑ Paul Bolin. Cauda Equina Syndrome - CRASH! USMLE Step 2 and 3. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8tEB4eMfE28 [last accessed 20/04/14]

- ↑ CES UK. Presentation - A Neurological Perspective of Cauda Equina Syndrome . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLnY_esmmhE [last accessed 20/04/14]

1. Jun W. et al. Cauda equina syndrome caused by a migrated bullet in dural sac. Turk Neurosurg 2010 Oct;20(4):566-9. [1C]

2. Shi J. et al. Clinical classification of cauda equina syndrome for proper treatment. Acta orthop 2010 Jun;81(3):391-5. [1B]

3. Boek: Dutton, M. (2008). Orthopaedic: Examination, evaluation, and intervention (2nd ed.). New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

4. John McNamee, Peter Flynn, [...], and Barry Kelly, Imaging in Cauda Equina Syndrome – A Pictorial Review, The ulster Medical Journal, Januarie 1, 2013. Pictorial review. [5]

5. Alex Gitelman, MD, Shuriz Hishmeh, MD, Brian N. Morelli, Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review, The American Journal of Orthopedics®, 2008. [3A]

6. Boek : Rovenský, Jozef; Payer, Juraj (Eds.), 2009, V, 230 pages. ‘Dictionary of rheumatic disease’

7. MA Bin, WU Hong, JIA Lian-shun, YUAN Wen, SHI Guo-dong and SHI Jian-gang, Cauda equina syndrome: a review of clinical progress, Chinese Medical Journal, 2009 [1A]

8. Stuart Fraser, Lisa Roberts, Eve Murphy, Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Literature Review of Its Definition and Clinical Presentation, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Volume 90, Issue 11, Pages 1964-1968, November 2009 [1A]

9. Shapiro S. Medical Realities of Cauda Equina Syndrome Secondary to Lumbar Disc Herniation. SPINE 2000;25:3, 348-52 [5]

10. Ogilvie J. Complications in Spondylolisthesis Surgery. SPINE 2005;30:65 S97-S101

11. Fraser S. et al. Cauda equina syndrome: a literature review of its definition and clinical presentation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Nov;90(11):1964-8. [1A]

12. Jiangang Shi, Lanshun Jia, Wen Yuan, GouDong Shi, Bin Ma, Bo Wang, and JianFeng Wu, Clinical classification of cauda equina syndrome for proper treatment, Acta Orthopeadica, 2010, Juni. [1B]

13. MA Bin, WU Hong, JIA Lian-shun, YUAN Wen, SHI Guo-dong, SHI Jian-gang, Cauda equina syndrome: a review of clinical progress, MA Chinese Medical Journal 2009; 122(10):1214-1222. [1A]

14. A. Gardner, E. Gardner and T. Morley, Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position, Eur Spine J. 2011 May; 20(5): 690–697. [1A]

15. Wagih E.M., Management of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries: current standard of care revisited, ACNR, Volume 10 Nr.1, March/April 2010 [3A]

16. Emiliana B., Agostino Z., Cristina M., Epidemiology and clinical management of Conus-Cauda Syndrome and flaccid paraplegia in Friuli Venezia Giulia: Data of the Spinal Unit of Udine, Basic Applied Myology 19 (4): 163-167, 2009 [1B]

17. Creasey GH., Craggs MD., Functional electrical stimulation for bladder, bowel and sexual function, Spinal Cord Injuries, 2012;109:247-57 [1A]

18. Karen M.B., Julie M.W., Timothy W.F., Lumbar spinal stenosis-diagnosis and management of the aging spine, Manual Therapy 16, 2011 (308-317) [1A]

19. Boek: Podnar S. Epidemiology of cauda equina and conus medullaris lesions. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(4):529–531. doi: 10.1002/mus.20696, 2006.

20. J. G. Kennedy, K. E. Soffe, A. McGrath, M. M. Stephens, Predictors of outcome in cauda equina syndrome, Eur Spine J, 12 april 1999. [2B]

21. Small S, Perron A, Brady W. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2005;23:159-63. [5]

22. David E. Trentham, Rheumatic disease clinics of North America ; Diagnostic Issues, Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, Volume 20, Number 2, May 1994 [5]

23. McCarthy MJ, Aylott CE, Grevitt MP, Hegarty J., Cauda equina syndrome: factors affecting long-term functional and sphincteric outcome, 2007 [2B]