Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury

This article requires a page merger with a similar article of a similar name or containing repeated information. (16 May 2024)

<div class="editorbox"

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Injuries to the ACL are relatively common knee injuries amongst athletes.[1] They occur most frequently in those who play sports involving pivoting (e.g. football, basketball, netball, soccer, European team handball, gymnastics, downhill skiing). They can range from mild such as small tears/sprain to severe when the ligament is completely torn. Both contact and non contact injuries occur allthough most common are non contact tears and ruptures.It appears that females tend to have a higher incidence of ACL injury than males. The incidence rate between 2.4 and 9.7 times higher in females athletes competing in similar activities.[2][3][4][5][6]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The knee is being stabilized by 4 ligaments:

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

- Medial collateral ligament

- Lateral collateral ligament

The role of the ACL is to prevent forward movement of the tibia from underneath the femur. It is less thick than the PCL and thus more likely to be injured.

The ligament has a proximal attachment in the fossa on the postero-medial aspect of the lateral condyle of the femur and terminates distally on the tibial plateau in front of and lateral to the anterior tibial spine. [7][8]The ACL has a multiple bundle structure which allows it to be functional at all knee angles. Two main aspects can be distinguished:

- Anteromedial part which is tight in knee flexion and lax in knee extension. It attaches on the proximal aspect of the femoral attachment and inserts on the anteromedial portion of the tibial insertion.

- Posterolateral band which is lax in flexion and tight in extension and partly prevents hyperextension. The fibers attach to the posterolateral aspect of the tibial attachment.

Mechanisms of injury / Pathological process

[edit | edit source]

Three major types of ACL injuries are distinguished:[9]

- Direct contact

- Indirect contact

- Non contact

Most common are the non contact injuries caused by forces generated within the athlete’s body while most other sport injuries involve a transfer of energy from a source external to the athlete’s body.[10] A cut-and-plant movement is the typical mechanism that causes the ACL to tear: sudden change of direction or speed with the foot firmly planted. A direct impact to the front of the tibia or stiff-legged landing are other frequently reported causes.

Women are three times more prone to have the ACL injured then men. It is due to following reasons[11]

- Smaller size and different shape fo the intercondylar notch

- Wider pelvis and greater Q angle

- Greater ligament laxity

- Shoe surface interface

- Neuromuscular factors

A wider pelvis requires the femur to angle toward the knee, lesser muscle strength gives less support to the knee and hormonal variations may alter the laxity of ligaments.[12][13]

Biomechanics of injury

[edit | edit source]

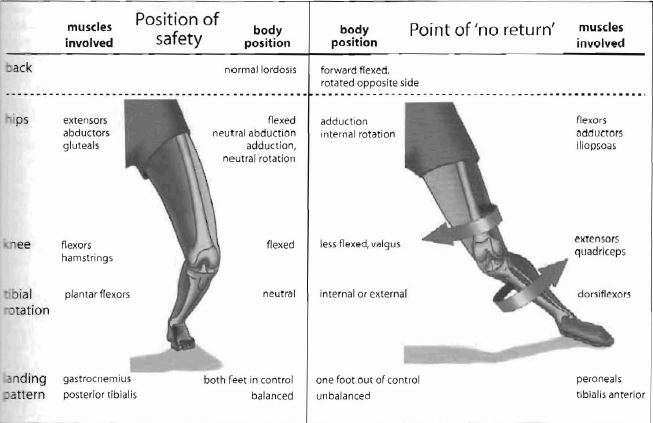

As 60-80% ofACT, injuries occur in non-contact siluations,it sccms likely that the appropriate prevention efforts are warranted.Cutting or sidestep maneuvers are associated with dramatic increases in the varus-valgus and internal rotation moments. The ACL is placed at greater risk with both varus and internal rotation moments. The typical ACL injury occurs with the knee externally rotated and in 10-30° of flexion when the knee is placed in a valgus position as the athlete takes off from the planted foot and internally rotates with the aim of suddcnly changing direction.(fig shown below).[14][15]The ground reaction force falls medial to the knee joint during a cutting maneuver and this added force may tax an already tensioned ACL and lead to failure. Similarly, in the landing injuries, the knee is close to full extension.High-speed activities such as cutting or landing maneuvers require eccentric muscle actio of the quadriceps to resist further flexion. It may be hypothesized that vigorous eccentric quadriceps muscle action may playa role in disruption of ACL. Although this normally may be insufficient to tear the ACL, it may be that the addition of valgus knee position and/or rotation could trigger an ACL rupture.[16]

The athlete could be off balance, be hed or held by an opponent, be trying to avoid collision with an opponent, or have adopted an unsually wide foot position. These perturbations contribute to the injury by causing the athlete to plant the foot so as to promote unfavorable lowerextremity alignment; this may be compounded by inadequate muscle protection and poor neuromuscular control.[17] Fatigue and loss of concentration may also be a factor. What has become recognized is that unfavorable body movements in landing and pivoting can occur,leading to what has become known as the'functional valgus' or 'dynamic valgus' knee, a pattern of knee collapse where the knee falls medial to the hip and foot. This has been called by Ireland the'position of no return', or perhaps it should be termed the 'injury prone position' since there is no proof that one cannot recover from this position (Fig below)[18]. Intervention programs aimed to reduce the risk of ACL injury are baseed on training safer neuromuscular patterns in simple maneuvers such as cutting and jump landing activities.[19]

Grades of injury

[edit | edit source]

An ACL injury is classified as a grade I, II, or III sprain. [20]

Grade I sprain

o The fibres of the ligament are stretched, but there is no tear.

o There is a little tenderness and swelling.

o The knee does not feel unstable or give out during activity.

o No increased laxity and there is a firm end feel.

Grade II sprain

o The fibres of the ligament are partially torn or incomplete tear with hemorrhage.

o There is a little tenderness and moderate swelling with some loss of function.

o The joint may feel unstable or give out during activity.

o Increase anterior translation, yet there is still a firm end point.

o Painful and pain increase with Lachman's and anterior drawer stress tests.

Grade III sprain

o The fibres of the ligament are completely torn (ruptured); the ligament itself has torn completely into two parts.

o There is tenderness (but not a lot of pain, especially when compared to the seriousness of the injury). There may be a little swelling or a lot of swelling.

o The ligament cannot control knee movements. The knee feels unstable or gives out at certain times.

o There is also rotational instability as indicated by a positive pivot shift test.

o No end point is evident.

o Hemarthrosis occurs within 1-2 hours.

An ACL avulsion occurs when the ACL is torn away from either the upper leg bone or lower leg bone. This type of injury is more common in children than adults. The termanterior cruciate dificient knee refers to a grade 3 sprain in which there is a complete tear of the ACL. It is generally accepted that a torn ACL will not heal.[21]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[1][edit | edit source]

- Occur after either a cutting maneuver or one leg standing,landing or jumping.

- There may be an audible pop or crack at the time of injury

- A feeling of initial instability, may be masked later by extensive swelling

- Episodes of "giving way" especially on pivoting or twisting motions. Patient has a "trick knee" and a predictable instability.

- A torn ACL is extremely painful, in particular immediately after sustaining the injury

- Swelling of the knee, usually immediate and extensive, but can be minimal or delayed

- Restricted movement, especially an inability to fully extension

- Possible widespread mild tenderness

- Tenderness at the medial side of the joint which may indicate cartilage injury

Associated Injuries[edit | edit source]

Injuries to ACL rarely occur in isolation. The presence and extent of other injuries may affect the way in which the ACL injury is managed.[22]

Meniscal Lesions[edit | edit source]

A torn ACL mostly does not occur isolated: over 50% of all ACL ruptures have associated meniscal injuries. If seen in combination with a medial meniscus tear and MCL injury, it is called O’Donohue’s triad.[1] which have 3 components

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL) tear / strain

- Meniscal tear

Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries[edit | edit source]

Associated injury to MCL (grade I-III) poses a particular problem due to tendency to develop stiffness after this injury. Most orthopaedic surgeon will first treat MCL injury in an limited motion knee brace for a period of six weeks, during which time the athlete would undertake a comprehensive rehabilitation program. Only then would ACL reconstruction be performed or be treated.[23]

Bone Contusions and Microfractures[edit | edit source]

Subcortical trabecular bone injury (bone bruise) may occur due to the pressures exerted on the knee in traumatic injury and are especially associated with ACL rupture. Associated injuries of the menisci and the MCL tended to increaset he progression of bone contusion[24]. The focal signal abnormalities in subchondral bone marrow seen on MRI (undetectable on rdiographs) are thought to represent microtrabecular fractures, haemorrhage and oedema without disruption of adjacent cortices or articular cartilage.[25] Bone contusions may occur in isolation to ligamentous or meniscal injury.[26]

Occult bony lesions have been reported in 84-98% of the patients with ACL rupture.[24][27][28] The majortiy of these have lesions of the lateral compartment[29], involving either the lateral femoral condyle, the lateral tibial plateau, or both. The boney bruising itself is unlikely to cause pain or reduced function.[30] Although the majority of bony lesions resolve, permanent alterations may remain. There is confusion in the literature as to how long these bony lesions remain hoever it has been reported that they can persist on MRI for years[31]. Rehabilitation and the long-term prognosis may be affected in those patients with extensive bony and associated articular cartilage injuries. In the case of severe bone bruising it has been recommended to delay return to full weightbearing status to prevent further collapse of subchondral bone and further aggravation of articular cartilage injury.[31]

Chondral Injury[edit | edit source]

Hollis et al suggested that all patients following traumatic ACL disruption sustained a chondral injury at the time of initial impact with subsequent longitudinal chondral degradation in compartments unaffected by the initial bone contusion a process that is accelerated at 5 to 7 years’ follow-up[32].

Tibial Plateau Fractures[edit | edit source]

A tibial plateau fracture is a bone fracture or break in the continuity of the bone occurring in the proximal part of the tibia or shinbone called the tibial plateau; affecting the knee joint, stability and motion. The tibial plateau is a critical weight-bearing area located on the upper extremity of the tibia and is composed of two slightly concave condyles (medial condyle and lateral condyle) separated by an intercondylar eminence and the sloping areas in front and behind it. It can be divided into three areas: the medial tibial plateau (the part of the tibial plateau that is nearer to the center of the body and contains medial condyle), the lateral plateau (the part of the tibial plateau that is farthest away from the center of the body and contains the lateral condyle) and the central tibial plateau (located between the medial and lateral pleateaus and contains intercodylar eminence).

These fractures are also cause by by a varus (inwardly angulating) or valgus(outwardly angulating) force combined with axial loading or weight bearing on knee and are occur rarely alone, mostly occure with ACL injuries. The fracture of lateral tibial plateau is also called as Seagond fracture which is most comman to occur with ACL injury.

Posterolateral Corner Injury[edit | edit source]

The stability of the posterolateral corner of the knee is provided by capsular and noncapsular structures that function as static and dynamic stabilizers[33] including the fibular collateral ligament, the popliteus muscle and tendon including its fibular insertion (popliteofibular ligament), and the lateral and posterolateral capsule. Injuries to this region that result in posterolateral rotatory instability can be but are uncommonly isolated; usually these injuries are associated with concurrent ligamentous injuries elsewhere in the knee.[34][35][36][37]High-grade posterolateral corner injuries are usually associated with rupture of one or both cruciate ligaments. Importantly, failure to address instability of the posterolateral corner structures increases forces at anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and PCL graft sites and may ultimately predispose to failure of the cruciate reconstruction.[38][39][40]

Popliteal Cyst[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures

[edit | edit source]

The exact diagnosis can be made by

1. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION which includes the following important tests to perform

2. RADIOGRAHS :

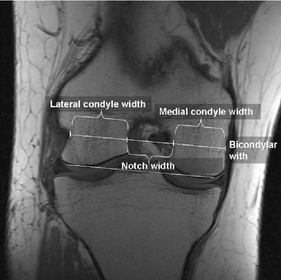

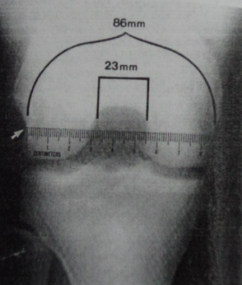

Radiographs of the knee should be performed when an ACL tear is suspected, this consist of an AP veiw, lateral veiw adn patellofemoral projection. the standing AP weight bearing veiw provides a way of evaluating the joint space between the femur and tibia.[41] It also allows for measurement of notch width index which is important predictive values for ACL tears.[42]. The patellar tendon and height are measured on lateral radiograph. A tunnel veiw in addition may be helpful. The Merchant's radiograph veiw [43] not only shows the joint space between the femur and patella but also helps to determine wheather the patient has patellofemoral malalignment. Following should me noticed clearfully in an X ray.

- Notch width index

- Osteochondral fracture

- Segond fracture

- Bone bruise

Notch width index is the ratio of the width of the intercondylar notch to the width of the distal femur at the level of the popliteal groove measured on a tunnel veiw roentgenogram of the knee. The normal intercondylar notch ratio was 0.231 ± 0.044. The intercondylar notch width index for men is larger than that of women. It was found that athletes with noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries had a notch width index that was at least 1 standard deviation below the mean which means that a person with ACL injury have presentation on small notch width index as campared to normal. It is measured with the help of ruler placed parallel to joint line. Narrowest portion of notch at level of ruler is to be measured.[44] In more chronic ACL injuries, there may be interchondral eminence spurring or hypertrophy,patellar facet osteophyte formation

This is also one of the reason that why women are more prone to have ACL injury as campared to men. It has also been seen that the value of inner angle of lateral condyle of femur was significantly higher in women athletes with ACL tear compared to those without. Value of width of intercondylar notch was statisticaly smaller in athletes with ACL tear, compared to those without. Also it was seen that the inner angle of lateral femoral condyle is better predicting factor for ACL tear in young female handball players compared to intercondylar notch width.[45]

In more chronic ACL injuries, there may be interchondral eminence spurring or hypertrophy,patellar facet osteophyte formation, and joint space narrowing with marginal osteophytes.It is particulary important in skeletally immature patients to have plain radiographic assesement. This is because there is frequently a ligamentous avulsion in this age group.

Bone bruise is usually present in conjunction with an ACL injury more than in 80% of cases.[46] The most comman site is over the lateral femoral condyle. The bone bruise is most likely caused by impaction between the posterior aspect of the lateral tibial plateau and the lateral femoral condyle during displacement of the joint at the time of the injury. The presence of bone bruise indicates impaction trauma to the articular cartilage.[47] Patients with bone bruise are more prone to develop osteoarthiritis later.[48] Bone bruise is more prominent in MRI.

Bone bruise diagrame Bone bruise in X ray Bone bruise in MRI

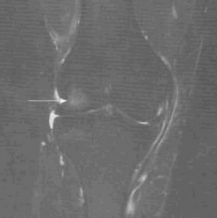

3. MRI:

MRI has the advantage of providing a clearly defined image fo all the anatomic sturctures of the knee. Normal ACL is seen as a well defined band of low signal intensity on sagittal image through the intercondylar notch. With an acute injury to the ACL , the continuity of the ligament fibers appears disrupted and the ligament substance is ill defined, with a mixed signal intensity representing local edema and hemarrhage. [49]

MRI can diagnose the ACL injuries with an accuracy of 95% or better.[50] MRI will also reveal any associated meniscal tears,chondral injuries or bone bruises.

'4. INTRUMENTED LAXITY TESTING/ARTHOMETRIC EVALUATION OF KNEE':

An adjunct ot the clinical special tests in assesing anterior translation is the use of instrumented laxity testing. The most commanly cited arthrometer is the KT1000 (Medmetric,San Diego,Calif). The arthrometer provides an objective measurement of the anterior translation of the tibia that supplements the Lachman test in ACL injury. It can be particularly useful in the examination of acutely injured patients in whom pain and guarding may preclude evaluation. In such patients the Lachman and other tests can be difficult to perform accurately. The arthrometeric results can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess ACL intergrity or as part of the follow up examination after ACL reconstruction.[51] The results of the KT1000 and its sibling. the KT 2000 have been noted to be both reliable and accurate.[52]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The same characteristics for an ACL injury can be found at knee dislocations and meniscal injuries andcollateral ligaments injury or posterolateral corner of the knee. Other problems that have to be considered are patellar dislocation or fracture, and a femoral, tibial or fibular fracture.

The differential diagnosis of an acute hemarthrosis of the knee due to ACL in addition to a major ligamentous tear would include meniscal tear or patellar dislocation or osteochondral fracture.

Differentiation can mostly be made based on a thorough examination with particular attention for the mechanism at time of injury. An additional MRI scan can visualize the injury.

Can you spot the ACL and associated injuries in the MRI below?

Examination[edit | edit source]

The examination of ACL injury can be done in two ways

- Physical/ Clinical examination

- Examination under anesthesia and arthroscopy

Physical/ Clinical Examination:

An organized, systematic physical examination is imperative when examining any joint. Immediately after the acute injury, the physical examination may be very limited due to apprehension and guarding by the patient.While inspecting, the examiner should look for

- overall alignment of the knee.[53]

- severe distortion of the normal alignment may represent a fracture of the distal femur or proximal tibia or indicate knee dislocation.[54]

- Any gross effusion, which most commanly be present within a few hours after an ACL injury. Absence of an effusion does not mean that an ACL injury has not occured; in fact, with more severe injuries that include the surrounding capusle and soft tissues, the hemarthrosis may be able to escape from the knee, and the degree of swelling may paradoxically be diminished. In addition, the presence of swelling an effusion does not guaurantee that an ACL injury has occured.[55]According to Noyes et al, in the absence of bony trauma, an immediate effusion is believed to have a 72% correlation with an ACL injury of some degree.

- Bony abnormality may suggest an associated fracture of the tibial plateau.

- Palpation follows inspection and should begin with the uninvolved extremity. Palpation confirms the presence and degree of effusion and bony injury. Subtle effusions missed during inspection should be picked up by the careful manual examination.[56]Palpation of joint lines and collateral ligaments can rule out a possible associated meniscus tear or sprained ligaments.

- Periarticular tenderness should also be examined.[57]

- Assessing the patient’s range of motion (ROM) should be carried out to look for lack of complete extension, secondary to a possible bucket-handle meniscus tear or associated loose fragment.[58]

- Laxity testing should be done either with the special test or with the help of arthrometer.

Examination under anaesthesia and arthroscopy:

Arthroscopy combined with examination under anesthesia is an accurate way to diagnose a tore ACL, it may be indicated in the case in which the diagnosis is suspected from the patient's history but is not evident on clinical examination. the main value of using arthroscopy on the basis of examination is to diagnose associate joint pathologic conditions such as meniscal tears or chondral fractures.[59][60]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Immediately after the trauma, the RICE principle should be applied.

Conservative treatment of isolated ACL tears (including physiotherapy and use of a knee brace) can have good outcome and may be indicated in patients:[61][62]

- with partial tears and no instability symptoms

- with complete tears and no symptoms of knee instability during low-demand sports who are willing to give up high-demand sports

- who do light manual work or live sedentary lifestyles

- whose growth plates are still open (children)

Surgical treatment is usually advised in dealing with combined injuries and for patients who frequently participate in high demand sports activities.

Physiotherapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Acute Stage[edit | edit source]

After ACL injury, regardless of whether surgery will take place or not, physiotherapy management focuses on regaining range of movement, strength, proprioception and stability.

PRICE should be used in order to reduce swelling and pain, to attempt full range of motion and to decrease joint effusion.

Exercises should encourage range of movement, strengthening of the quadriceps and hamstrings and proprioception. Consider integrating any of these exercises into a rehabilitation programme at this stage as is appropriate for the client:

- SQs/SLR

- ankle DF/PF/circumvention

- Knee flexion/extension slides in sitting

- Patellar mobilisations

- Glut Med work in side lying

- Gluteal exercises in prone

- Knee flexion in prone (gentle kicking exercises)

- weight transfers in standing (forwards/backwards, side/side)

NMES combined with exercise is more effective in improving quadriceps strength than exercise alone[63].

Also consider taping to provide stability and to encourage reduction in swelling.

Rehabilitation Stage[edit | edit source]

Once pain and swelling have reduced and normal range of movement has returned the knee should be rehabilitated to regain full stability and function. The more equal the injured leg is in strength and range of movement compared to the unijured leg, the better any outcome will be post surgery. For rehabilitation see Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Given the importance of neuromuscular factor the etiology of ACL injuries, numerous progam have aimed to improve neuromuscular control during standing, cuting, jumping and landing.[64] The component of neuromuscular training are:

- Balance training

- Landing with increaded flexion at the knee and hip

- Controlling body motions, especially in deceleration and pivoting maneuvers

- Some form of feedback to the athlete during training of these activities

- Also following the PEP plan.(in the video below)

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00549

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/acl-injury/DS00898

http://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/sport-injuries/knee-pain/acl-injury

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

In order to provide the injured athlete with the best care, physiotherapists should have elaborate knowledge of anatomy and functioning of the ACL.The key stone to have proper care of ACL injury start from its correct and diagnosis withing first one hour of injury before the development of tense hemarthrosis. This should include the detection and diagnosis of associate injuries also.[65] The treatment for the injury and the return to play for an athlete depends completely upon the grade and associated injuries.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1LoKNAID323NNuX1ch6EpTuMFzpvQXK20XCjKWtmWuCqaJdI65|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Yasuharu Nagano, Hirofumi Ida, Masami Akai, Toru Fukubayashi. Biomechanical characteristics of the knee joint in female athletes during tasks associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee 2009; 16(2): 153-158

- ↑ Arendt E,Dick R. Knee injuries patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of literature. Am J Sports Med 995;23:694-701

- ↑ Arendt EA, Agel J,Dick R.Anterior cruciate ligament injury patterns among collegiate men and women. J Athl Train 1999;34:86-92.

- ↑ Garrick JG, Requa RK. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in men and women: how common are they? In: Griffin LY, ed. Prevention of noncontact ACL injuries. Rosemont,IL:American Academy Orthopaedic Surgeons,2001:1-10.

- ↑ Agel J,Arendt E,Bershadsky B.Anterior cruciate ligament inury in national collegiate athletic association basketball and soccer: a 13 year review.Am J Sports Med 2005;33(4):524-30.

- ↑ Beynnon BD,Johnson RJ,Abate JA,et al. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, Part 1. Am J Sports Med 2005;33(10):1579-602.

- ↑ M. Kjaer, M.Krogsgaard, P.Magnusson, L.Engebretsen, H.Roos, T.Takala, S.L-Y Woo. Textbook of Sports Medicine. Blackwell Science. Hong Kong. 2003

- ↑ R. Putz, R. Pabst. Sobotta atlas van de menselijke anatomie. Bon Stafleu Van Loghum. Houten/Diegem. 2002

- ↑ T.E. Hewett,S.J. Shultz,L.Y. Griffin, Understanding and Preventing Noncontact ACL Injuries. American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. 2007

- ↑ M. Darrow. The knee Sourcebook. The McGraw-Hill Companies. USA. 2007

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Ch 27.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ (2005). "Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak knee valgus moment during sidestepping: implications for ACL injury". Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 20 (8): 863–70

- ↑ Mountcastle, Sally; et al. "Gender Differences in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Vary With Activity. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 35.10 (2007)

- ↑ Olsen OE,Myklebust G,Engebretsen L, et al.Injury mechanisms for anterior cruciate ligament injuries in team handball: a systematic video analysis.Am J Sport Med 2004;32(4):1002-12.

- ↑ Teitz CC.video analysis of ACL injuries. In:Griffin LY, ed. Prevention of Non contact ACL injuries.Rosemont,IL: American Academy Orthopaedic Surgeons,2001

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Ch 27.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ Teitz CC.video analysis of ACL injuries. In:Griffin LY, ed. Prevention of Non contact ACL injuries.Rosemont,IL: American Academy Orthopaedic Surgeons,2001

- ↑ Ireland ML.Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young female athletes.Your Patient &amp;amp; Fitness 1996;10(5):26-30.

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Ch 27.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ William E.Prentice, Rehabilitation techniques for sports medicine and athletic training; fourth ed.Mc Graw Hill publications.

- ↑ Souryal.T.T.Freeman, and J.Evans.1993. Intercondylar notch size and ACL injuries in atheletes: a prospective study. Am. J. of Sports Med.21:535-39.

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.page 483.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Ch 27,pg 483.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Yoon KH, Yoo JH, Kim KI.J. fckLRBone contusion and associated meniscal and medial collateral ligament injury in patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Aug 17;93(16):1510-8.

- ↑ Dorothy M. Niall and Vladimir Bobic. Bone Bruising and Bone Marrow Edema Syndromes: Incidental Radiological Findings or Harbingers of Future Joint Degeneration? International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine [Accessed online 20th January 2012 at http://www.isakos.com/innovations/niall.aspx]

- ↑ Rick W. Wright, Mary Ann Phaneuf, Thomas J. Limbird and Kurt P. Spindler. Clinical Outcome of Isolated Subcortical Trabecular Fractures (Bone Bruise) Detected on Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Knees. Am J Sports Med September 2000 vol. 28 no. 5 663-667

- ↑ Mark A. Rosen, Douglas W. Jackson, Paul E. Berger. Occult osseous lesions documented by magnetic resonance imaging associated with anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related SurgeryfckLRVolume 7, Issue 1 , Pages 45-51, March 1991

- ↑ R.B. Frobell, H.P. Roos, E.M. Roos, M.-P. Hellio Le Graverand, R. Buck, J. Tamez-Pena, S. Totterman, T. Boegard, L.S. Lohmande. The acutely ACL injured knee assessed by MRI: are large volume traumatic bone marrow lesions a sign of severe compression injury? Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 16, Issue 7, July 2008, Pages 829-836

- ↑ Viskontas DG, Giuffre BM, Duggal N, Graham D, Parker D, Coolican M. Bone bruises associated with ACL rupture: correlation with injury mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 2008 May;36(5):927-33. Epub 2008 Mar 19.

- ↑ Szkopek K, Warming T, Neergaard K, Jørgensen HL, Christensen HE, Krogsgaard M. Pain and knee function in relation to degree of bone bruise after acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011 Apr 8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01297.x. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Atsuo Nakamae, Lars Engebretsen, Roald Bahr, Tron Krosshaug and Mitsuo Ochi. Natural history of bone bruises after acute knee injury: clinical outcome and histopathological findings. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, Volume 14, Number 12, 1252-1258

- ↑ Hollis G. Potter, Sapna K. Jain,Yan Ma, Brandon R. Black, Sebastian Fung and Stephen Lyman. Cartilage Injury After Acute, Isolated Anterior Cruciate Ligament TearfckLRImmediate and Longitudinal Effect With Clinical/MRI Follow-up. Am J Sports Med February 2012 vol. 40 no. 2 276-285

- ↑ Baker CL, Norwood LA, Hughston JC. Acute posterolateral rotatory instability of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am1983 ; 65:614 –618

- ↑ Chen FS, Rokito AS, Pitman MI. Acute and chronic posterolateral rotatory instability of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000; 8:97 –110

- ↑ Fanelli GC, Edson CJ. Posterior cruciate ligament injuries in trauma patients: part II. Arthroscopy1995 ; 11:526 –529

- ↑ Davies H, Unwin A, Aichroth P. The posterolateral corner of the knee: anatomy, biomechanics and management of injuries. Injury 2004; 35:68 –75

- ↑ Fanelli GC. Surgical reconstruction for acute posterolateral injury of the knee. J Knee Surg 2005;28 : 157–162

- ↑ Moorman CT 3rd, LaPrade RF. Anatomy and biomechanics of the posterolateral corner of the knee. J Knee Surg2005 ; 18:137 –145

- ↑ Harner CD, Vogrin TM, Hoher J, Ma CB, Woo SL. Biomechanical analysis of a posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: deficiency of the posterolateral structures as a cause of graft failure. Am J Sports Med 2000; 28:32 –39

- ↑ LaPrade RF, Resig S, Wentorf F, Lewis JL. The effects of grade III posterolateral knee complex injuries on anterior cruciate ligament graft force: a biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med1999 ; 27:469 –475

- ↑ Rosenberg TD,Paulos LE, Parker RD, et al: The 45-degree posteroanterior flexion weight- bearing radiograph of the knee.J Bone Joint Surg 1988;70A:1479-1483.

- ↑ Shelbourne KD,Davis TJ, Klootwyk TE. The relationship between intercondylar notch width of the femur and the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears. A prospective study.Am J Sports Med 1998;26:402-408

- ↑ Merchant A: Patellofemoral malalignment and instabilities. In: Ewing JW,ed. Articular cartilage and knee joint function: basics science and arthroscopy. New York; Raven press.1990:79-91.

- ↑ Souryal TO, Moore HA, Evans JP,Intercondylar notch size and anterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes.A prospective study: Am J Sports Med 16:449,1988.

- ↑ Miljko M, Grle M, Kozul S, Kolobarić M, Djak I.Intercondylar notch width and inner angle of lateral femoral condyle as the risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury in female handball players in Herzegovina;Coll Antropol. 2012 Mar;36(1):195-200.

- ↑ beynnon BD,Johnson RJ,Abate JA,et al.Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries,part 1.Am J Sports Med 2005;33(10):1579-602.

- ↑ Johnson DL, Urban WP,Caborn DNM,et al. Articuar cartilage changes seen with magnetic resonance imaging detected bone bruise associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med 2005;33(1):131-48.

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.

- ↑ Turner da,Podromos CC, Petsnick JP, Clark JW: Acute injury of the knee: Magnetic resonance evaluation.Radiology 154:711-722,1985.

- ↑ Nogalski MP,Bach BR Jr: Acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries.In Fu FH,Harner CD,Vince KG: Knee surgery. Baltimore, Williams&amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins,1994,pp 679-730.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ Kowalk DL,Wojtys EM,Disher J,Loubert P:Quantitative analysis of the measuring capabilities of the KT1000 knee ligament arthrometer. Am J Sports Med 21:744-747,1993.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeLee, Drez,Muller. Orthopaedic sports Medicine,Principles &amp;amp;amp; Practice. Vol 2; 2nd edition.Saunder's publication, printed in USA.

- ↑ DeHaven KE:Diagnosis of acute knee injuries with hemarthrosis,Am J Sports Med 8:9,1980.

- ↑ Noyes FR et al: Arthroscopy in acute traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee, J Bone Joint Surg 62A:687,1980

- ↑ D E Meuffels, M M Favejee, M M Vissers, MP Heijboer, M Reijman, J Verhaar. Ten year follow-up study comparing conservative versus operative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. A matched-pair analysis of high level athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009; 43(5):347-351

- ↑ J. Craig Garrison, Douglas Wyland. Rehabilitation Following a Minimally Invasive Procedure for the Repair of a Combined Anterior Cruciate and Posterior Cruciate Ligament Partial Rupture in a 15-Year-Old Athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40(5):297-309

- ↑ Kyung-Min KiM, Ted Croy, Jay HerTel, SuSan Saliba. Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction on Quadriceps Strength, Function, and Patient-Oriented Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40(7):383-391.

- ↑ Hewett TE,Lindenfield TN,Riccobene JV, et al.The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study.Am J Sports Med 1999;27:699-706.

- ↑ Brukner, Khan. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd edition.Ch 27.Tata McGraw- Hill Publishing. New Delhi.