Acromioclavicular Joint Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 171: | Line 171: | ||

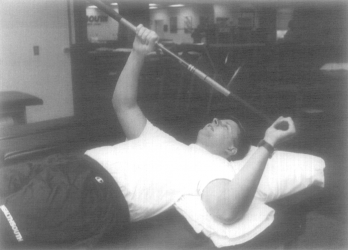

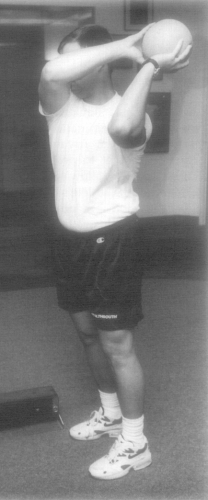

Plyos (dynamic stretch shortening): medicine ball toss and catch, tubing plyos. Sport specific exercises: a two-hand overhead side to side throw for the overhead athlete.<br> | Plyos (dynamic stretch shortening): medicine ball toss and catch, tubing plyos. Sport specific exercises: a two-hand overhead side to side throw for the overhead athlete.<br> | ||

[[Image:AJD Plyometric ex.png|center|210x500px]] | [[Image:AJD Plyometric ex.png|center|210x500px]] | ||

{{#ev:youtube|aLj--YqCXhw|412}} | {{#ev:youtube|aLj--YqCXhw|412}} | ||

==== Return to sport ==== | |||

Return to sport guideline: | Return to sport guideline: | ||

*Grade I: 2-4 weeks | *Grade I: 2-4 weeks | ||

*Grade II: 4-8 weeks | *Grade II: 4-8 weeks | ||

Revision as of 20:52, 10 January 2018

Original Editors - Mathilde De Dobbeleer

Top Contributors - Mostafa Mataich, Kim Jackson, Mathilde De Dobbeleer, Scott Cornish, Ilona Malkauskaite, Lien Hennebel, Admin, Yuli-Karisma Borremans, Rachael Lowe, George Prudden, Kai A. Sigel, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Fasuba Ayobami, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Vidya Acharya, Borms Killian, Wanda van Niekerk, Venus Pagare, Tarina van der Stockt, Tony Lowe, Oyemi Sillo, Amanda Ager, Naomi O'Reilly, Lucinda hampton and Olajumoke Ogunleye - Killian Borms, Haytem Mkichri, Anna Jansma, Yassin Khomsi.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Disorders is a general term to cover a range of conditions. It can be due to trauma, such as joint dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint or degenerative conditions, such as osteoarthritis.[1] An acromioclavicular dislocation is a traumatic dislocation of the joint in which a displacement of the clavicle occurs relative to the shoulder.[2]

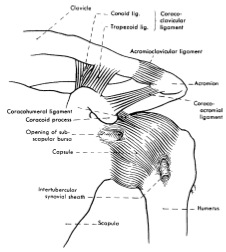

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The acromioclavicular joint is a diarthrodial joint with an interposed fibrocartilagninous meniscal disc that connects the clavicle with the acromion. It has an intra-articular synovium and an articular cartilage interface[3] and is characterised by the various angles of inclination in the sagittal and coronal planes and by a disc. 2 types of disc have been observed; a complete disc (very rare) and a meniscoid-like disc. [4].[5] The acromioclavicular joint is surrounded by a capsule and reinforced by the superior/inferior capsular ligaments with the coracoclavicular ligaments (trapezoid and conoid) also important structures for stability of the joint.[6]

The acromioclavicular (AC) ligament and coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments are part of the static stabilisers of the joint. The AC ligament controls horizontal stability in the anteriorposterior plane whilst the CC ligaments serve to control vertical stability. The conoid part of this ligament attaches posteriorly and medially on the clavicle with the trapezoid part attaches anteriorly and laterally. The trapezius and deltoid muscles also provide dynamic stabilisation of the AC joint.[7]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Injuries to the AC Joint account for approximately 10% of acute injuries to the shoulder girdle, with separations of the AC Joint accounting for 40% of shoulder girdle injuries in athletes. Commonly, injury happens when falling onto an outstretched hand or elbow, direct blows to the shoulder, or falling onto the point of the shoulder.[6]

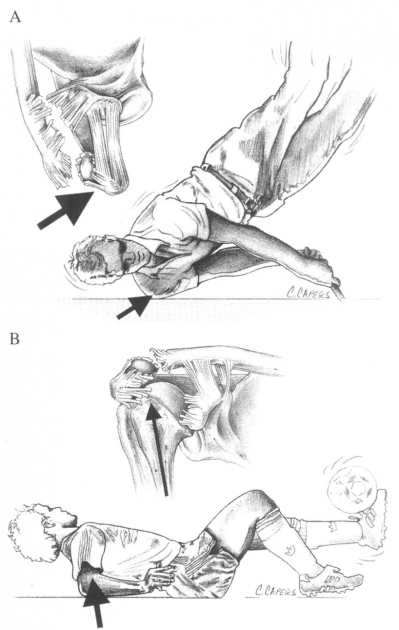

Figure 2 illustrates the common mechanism of injury:

(A) a direct force onto the point of the shoulder

(B) indirect forces to the AC joint can also cause injury. For example ,a fall on to the elbow can drive the humerus proximally, disrupting the AC joint. In this case, the force is referred only to the AC ligaments and not the coracoclavicular ligaments.[8]

The injury is frequently seen in hockey and rugby players, but is also seen in alpine skiing, snowboarding, football, cycling and motor vehicle accidents. [9][10]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

With an AC joint injury pain is often felt radiating to the neck and deltoid. The AC joint may also becme swollen, the upper extremity often held in adduction with the acromion depressed, which may cause the clavicle to be elevated.[11]

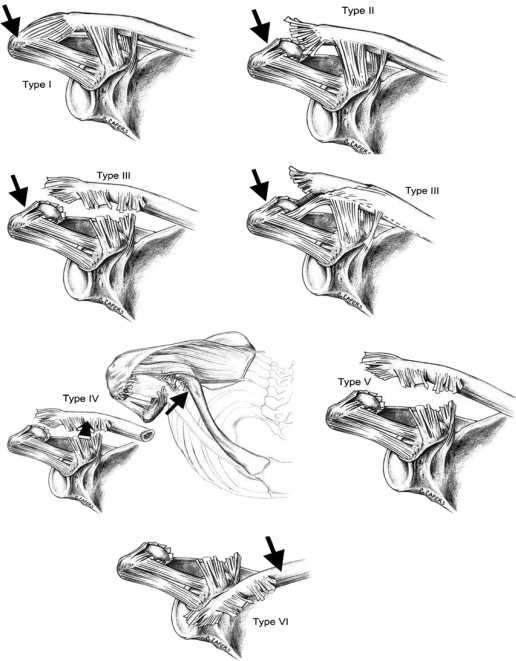

Allman et al described a 3 grade classification with Rockwood and Green expanding this to a 6 grade classification model (known as the Rockwood grades). This classification of AC joint injuries assists in deciding on appropriate treatment options and helps to avoid complications by failure to recognise the pattern of injury. [12]

| Grade |

Description |

Observation/Testing |

|---|---|---|

| I |

Sprain of AC ligaments. The AC and CC ligaments are intact |

No instability of clavicle detected on stress tests |

| II |

AC ligaments are ruptured, CC ligaments are intact. Often described as a subluxation. |

Clavicle is unstable to direct stress tests |

| III |

Complete disruption of both the AC and CC ligaments without significant disruption of the delto-trapezial fascia. This is often described as a dislocation. |

Deformity present with clavicle appearing elevated (acromion depressed), clavicle unstable in both vertical and horizontal plane |

| IV |

Distal clavicle is posteriorly displaced into trapezius muscle |

Posterior deformity present. |

| V |

More severe form of grade III. Complete disruption of both the AC and CC ligaments with disruption of the delto- trapezial fascia. |

Pseudo lateral clavicle elevation, downward displacement of the scapular. |

| VI |

Inferior displacement of the distal clavicle, either subacrominal or subcoracoid |

Severe trauma, usually accompanied by other significant injuries. |

Using digital measurement instead of a solely visual diagnosis is recommended because of the higher intra- and interobserver reliability.[13]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Most dislocations are situated in the Glenohumeral joint and 90% of this dislocations are anterior which can cause concomitant pathologies such as a Hill sachs lesion or injury of the brachial plexus. [14]

- Pain in the AC joint from osteoarthritis or disc disease[15]

- Osteolysis of the distal clavicle [16]

- Instability of the AC joint [16]

- Rotator-cuff impingement or tear [16]

- Adhesive capsulitis [16]

- Thoracic outlet syndrome [16]

- Superior labral tears [16]

- Complex pain syndrome [16]

- Shoulder dislocation [6]

- Anterior humerus subluxation [6]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Acromioclavicular dislocation is often diagnosed via radiography. Possible problems can occur with patients suffering from a type I injury as nothing abnormal is evident on a radiograph. Diagnosis is therefore determined by the mechanism of injury and tenderness over the AC joint.[17]

- Resisted AC Joint Extension Test

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- DASH: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaires.[12]

- Simple Shoulder Test questionnaires: Purpose is to assess functional disability of the shoulder, scored from 12 questions: 2 about function related to pain, 7 about function/strength and 3 about range of motion [12]

- Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): The primary outcome measure is the patients’ perceived level of pain and disability. It consists of 2 subscales, pain and disability, which are combined to produce a total score ranging from 0 (no pain or functional difficulty) to 100 (highest level of pain and functional difficulty). The SPADI is reliable, valid, and responsive for shoulder pain of musculoskeletal, neurogenic, or undetermined origin. [18]

- American Shoulder Elbow Surgeon (ASES): This measures functional limitations and pain in patients with musculoskeletal shoulder pathologies. The functional score is calculated from 10 questions relating to function using a 4 point scale.[18]

Examination[edit | edit source]

- AC Joint Palpation for Tenderness

- O’brien test: Examination using the O’Brien test tightens the posterior capsule and posteriorly translates the humeral head, stressing the labrum resulting in pain and weakness.

- Paxinos sign: Provocative testing for acromioclavicualr joint injury[11] [20]. Walton et al found that the Paxinos test is a good clinical diagnostic tool and bone scanning is the most reliable imaging modality for the diagnosis of AC joint pathology. When both of these tests are positive, there is a high degree of confidence for a diagnosis of AC joint pathology [20].

- Test of Stenvers 4: Clavicular Roll

- Resisted AC Joint Extension Test

A history of the mechanism of injury and palpation of the AC joint help to differentiate between a type I and a type II injury. A minor deformity in the AC joint is indicative of a type II injury. In a type I injury, swelling is usually present with pain on abduction of the arm, whereas with a type II pain is usually experienced in all movements of the arm. An obvious step deformity of the AC joint indicates a type III injury and the patient usually supports the injured arm as close as possible to his body.[21]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treating an AC joint injury will vary depending on its severity.

Nonoperative treatment is recommended for type I and type II AC separations, but for type III this is still much debated, as there is a high chance of early onset degenerative within the joint. However surgical intervention may be chosen as in certain cases this may yield better functional results, especially where the patient is younger, highly active or where a type III injury does not respond to conservative management. For type IV and V surgical repair is highly recommended.

There are several surgical methods, but the 4 most common surgical options are:

- AC joint fixation using hook-plates

- coracoacromial ligament transfer

- coracoclaviculair interval fixation

- a coracoclaviculair ligament reconstruction.[23][24]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Types I and II[edit | edit source]

Initial treatment should adhere to the RICER protocol, rest, ice, compression, elevation and referral within the first 48 hours and NSAIDs. A sling should be used to immobilise the shoulder along with keeping the shoulder in a elevated position when at rest. Taping to help support the joint can also be useful.

A sling can be in situ until the pain subsides. Return to normal activities is normally around 2-4 weeks for a type I injury, 4-6 weeks for a type II and 6-12 weeks for a type III[12]. For patients whose symptoms do not improve within this frame, intra-articular steroid injections may be indicated [24]

There is, however, a lack of evidence regarding rehabilitation protocols. Reid et al developed a best practice guideline after a systematic review of current practice[12]

Acute Phase[edit | edit source]

Range of motion (ROM): passive, active-assisted, active

- Glenohumeral Joint (GHJ): Internal rotation, external rotation, flex to tolérance : towel slides, pendular exercises

- Scapula: protraction, retraction, elevation, depression

- Active-assisted exercise using a L bar for Internal and external rotation: GHJ 30° to 45° abduction, 30° to 40° forward flexion:

Soft tissue: manage tightness

- Pectoralis minor stretch

- Posterior part of the GHJ: sleeper stretch

Isometric exercises: should be multi-angle, submaximal and subpainful

Closed Kinetic Chain: (no weight)

- hand supported in various planes and levels of elevation, control scapula position and progress to 90°

- elbow supported internal rotation/external rotation

- wall slides, scapula clock

- push-ups on wall

Recovery Phase[edit | edit source]

Avoid aggravation of the injury: example of exercises are bench press, prone press-ups, shoulder press or dips. Proximal stability must be reached before strength.

Range of motion: regain full range of motion of GHJ (including horizontal adduction), IR/ER at 90° abduction GHJ and capsular stretches.

Closed kinetic chain: increase the loads of previous closed kinetic chain exercises. Add active arm elevation and rotation.

Axial loaded active ROM (transition from closed kinetic chain to open kinetic chain (OKC)):

- wall slides with trunk and lower limb work

- wall slides in the scapular plane

Kinetic chain:

- trunk and hip extension (scapular retraction) e.g. low row exercices

- trunk and hip flexion (scapular protraction) e.g. punches

- bilateral and unilateral pull with trunk rotations, e.g. upper cuts

- Deltotrapezial complex work : exercises with cables, shrugs, abduction at various angles

Plyos (dynamic stretch shortening): medicine ball toss and catch, tubing plyos. Sport specific exercises: a two-hand overhead side to side throw for the overhead athlete.

Return to sport[edit | edit source]

Return to sport guideline:

- Grade I: 2-4 weeks

- Grade II: 4-8 weeks

- Grade III: 6-8 weeks

Post-operative Types V and VI

Type V and VI are considered to require surgical repair.

Hook Plate: post-operative therapy

Post-operatively, the arm is immobilised in a sling for 4 weeks. Patients are instructed not to perform tasks that will bring their arm above their head. During this time, the patient engages in physical therapy, including passive motion twice a week. After 4 weeks, the patient is allowed to elevate and abduct the arm actively to a level of 90°. The plate is removed after 12 weeks.[25]

Post-operative treatment follows similar guidelines as that for Type I and II injuries, but the duration of sling use is longer at around 3 to 4 weeks. Treatment consists initially of ROM exercises, followed by progressive strengthening. Rehabilitation needs to be followed through to full strength and mobility in order to avoid incidence of persistent pain and instability of the AC joint.[26][27]

Studies comparing the results of non-operative and surgical treatment of type III AC separations have shown that surgical interventions do not have a substantial benefit. Bannister et al concluded that conservative management of type III injuries yielded a return to full shoulder kinematics more quickly with less complications.[28] Conservative management should be considered as the first line of treatment for type III separations [29]

For type IV and V injuries there is no evidence based literature recommending a specific treatment for these injuries. Surgery is the preferred treatment, but there has been a reported case of the successful use of manual reductions, which converted the type IV to a type II.[30]

Taping

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Reid D, Polson K, Johnson L. Acromioclavicular Joint Separations Grades I–III A Review of the Literature and Development of Best Practice Guidelines. Sports Med 2012; 42 (8): 681-696.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

ACJ injuries are usually as the result of trauma, falling onto an outstretched arm or a direct blow to the shoulder. Pain may radiate out and the joint may become swollen. 6 grades of injury have been described with anything above a grade 3 requiring surgery. Grades 1 and 2 can be treated conservatively and grade 3 management remains much debated although a non surgical approach should be tried initially. Depending on the mechanism of injury there may be concomitant injuries such as hills sachs lesion and examination and treatment should reflect the history of the injury and activity background of the patient

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Codsi JM. The painful shoulder: when to inject and when to refer. Cleveland clinic journal of medicine 2007; 74(7): 473-482. (level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Heijmans E, Eekhof J; Neven AK. Acromioclaviculaire luxatie, huisarts & wetenschap, november 2010(level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Saccomanno MF. Acromioclavicular joint instability: anatomy, biomechanics and evaluation. Joints 2014; 2(2): 87–92.

- ↑ De Palma AF. Surgical anatomy of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1541–1550.

- ↑ Salter EG, Jr, Nasca RJ, Shelley BS. Anatomical observations on the acromioclavicular joint in supporting ligaments. Am J Sports Med 1987;15(3):199-206.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Magee DJ, Zachazewski JE, Quillen WS. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation.fckLRElsevier Health Sciences, 2008.

- ↑ Suezie K, Blank A, Strauss E. Management of Type 3 Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocations Current Controversies. Bulletin of the Hospital for Joint Diseases 2014; 72(1): 5360.

- ↑ Beim GM. Acromioclavicular joint injuries. Journal of Athletic Training 2000;35(3):261-267.

- ↑ Johansen JA, Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Petersen SA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: indications for treatment and treatment options. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20:70-82.

- ↑ Culp LB, Romani WA. Physical Therapist Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention Following the Surgical Reconstruction of a Grade III Acromioclavicular Joint Separation. Journal of the American physical therapy association 2006; 86:857-869.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Micheli LJ. Encyclopedia of Sports Medicine. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Reid D, Polson K, Johnson L, Acromioclavicular Joint Separations Grades I–III A Review of the Literature and Development of Best Practice Guidelines. Sports Med. 2012; 42(8): 681-696.

- ↑ Schneider MM, Balke M, Koenen P, Fröhlich M, Wafaisade A, Bouillon B, Banerjee M. Inter- and intraobserver reliability of the Rockwood classification in acute acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016; 24(7): 2192-6.

- ↑ Nepola VJ, Newhouse EK, Recurrent shoulder dislocation. The iowa orthopaedic journal 1993; 13: 97-106

- ↑ Robb AJ, Howitt S, Conservative management of a type III acromioclavicular separation: a case report and 10-year follow-up. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2011; 10: 261–271.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Fraser-Moodie JA, Shortt NL, Robinson CM. Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008 ;90-B: 697-707.

- ↑ 4. Johansen JA, Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Petersen SA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: indications for treatment and treatment options. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20 p.S70-82

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Harris KD, Deyle GD, Gill NW, Howes RR. Manual Physical Therapy for Injection-Confirmed Nonacute Acromioclavicular Joint Pain. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 2012; 42(2): 66-80.

- ↑ Physiotutors. AC Joint Line Tenderness | Acromioclavicular Joint Pathology. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U31quA3ZsjY

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Walton J, Mahajan S, Paxinos A, Marshall J, Bryant C, Shnier R, Quinn R, Murell GAC. Diagnostic Values of Tests for Acromioclavicular Joint Pain. The Journal Of Bone & Joint Surgery 2004; 86-A (4): 807-812.

- ↑ Culp LB, Romani W. Physical Therapist Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention Following the Surgical Reconstruction of a Grade III Acromioclavicular Joint Separation. Journal of the American physical therapy association 2006; 86:857-869.

- ↑ Physiotutors. AC Joint Provocation Cluster | Acromioclavicular Joint Pathology. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npHPXrV6_JI

- ↑ Johansen JA, Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Petersen SA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: indications for treatment and treatment options. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20: S70-82

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Hootman JM. Acromioclavicular Dislocation: Conservative or Surgical Therapy. Athl Train. 2004; 39(1):10–11.

- ↑ Gstettner C, Tauber M, Hitzl W, Resch H. Rockwood type III acromioclavicular dislocation: surgical versus conservative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008; 17(2): 220-225.

- ↑ Johansen JA, Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Petersen SA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: indications for treatment and treatment options. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011; 20: S70-82

- ↑ Glick JM, Milburn LJ, Haggerty JF, Nishimoto D. Dislocated acromioclavicular joint: follow-up study of 35 unreduced acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med 1977; 5: 264-70.

- ↑ Bannister GC, Wallace WA, Stableforth PG, Hutson MA. The management of acute acromioclavicular dislocation. A randomised prospective controlled trial. Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989; 71(5): 848-850.

- ↑ Nissen CW, Chatterjee A. Type III acromioclavicular separation: results of a recent survey on its management. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2007 Feb. 36(2):89-93.

- ↑ Johansen JA, Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Petersen SA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: indications for treatment and treatment options. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20 p.S70-82

- ↑ KT Tape. KT Tape: AC Joint. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJEhxOkg8Pg [last accessed 28/3/15]