Physical Inactivity in Children with Asthma: A Resource for Physiotherapists: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kapil Narale (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (405 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[ | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:User Name|Amy Murray]], [[User:User Name|Chrisostomos Koutsos]], [[User:User Name|David Cowan]], [[User:User Name|Rui Ling Lee]], [[User:User Name|Shuen Wen Lim]] and [[User:User Name|Tommy Flanagan]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Childhood [[asthma]] is the most common chronic illness in the world<ref name="WHO, 2013">World Health Organization. Asthma. http://www.who.int/respiratory/asthma/en/ (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. The UK has among the highest prevalence rates of asthma symptoms in children worldwide, with 1 child being admitted to the hospital every 20 minutes for an asthma attack<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />. This highlights that there is a significant proportion of children suffering from this illness. Despite global efforts to raise awareness of the importance of [[Physical Activity|physical activity]] and the benefits that follow<ref name="WHO, 2016">World Health Organization. Physical activity. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/ (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>, children with asthma are still engaging in less physical activity due to their perceived barriers<ref name="Glazebrook et al. 2006">Glazebrook C, McPherson A, MacDonald I, Swift J, Ramsay C, Newbould R, Smyth A. Asthma as a barrier to children’s physical activity: Implications for body mass index and mental health. Pediatrics 2006;118;2443-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17142530 (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. This strongly suggests the need for education to change the misguided beliefs that exercise will do more harm than good. Although there are organisations such as Asthma UK<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />, SIGN<ref name="SIGN, 2016">SIGN. British guideline on the management of asthma. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/ (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref> and NICE<ref name="NICE, 2013">NICE. Asthma. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25/chapter/Introduction-and-overview (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref> in place to raise awareness of asthma management in children, these current guidelines only emphasise the importance of pharmacological interventions. There are gaps as to what physiotherapy services can offer to a child with asthma. Therefore, there is a need for this resource to equip physiotherapists with the appropriate knowledge and skills to handle asthma management in children and to promote health. | |||

< | |||

= | |||

This | |||

[[ | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

According to the Global asthma report which was produced in 2014 by the Global Asthma Network<ref name="Global Asthma Network, 2014">Global Asthma Network. Global asthma report. http://www.globalasthmanetwork.org/index.php (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref> (GAN) the most recent revised estimate is said to be approximately 334 million people that suffer from asthma worldwide and therefore the burden of disability is extremely high. This figure is inclusive of both adults and children. GAN is part of a worldwide collaboration that includes over half of the world's countries in order to statistically analyze asthma and the potential difficulties it can cause, in order to provide data required by the World Health Organisation<ref name="Asher and Pearce, 2014">Asher I, Pearce N. Global burden of asthma among children. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2014;18;1269-1278. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25299857 (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. | |||

== Childhood Asthma == | |||

According to the the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child, a child is defined as everyone under the age of 18 unless, "under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier"<ref name="United Nations, 1996">United Nations. Convention to the rights of the child. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (Accessed 25 January 2017).</ref>.<br> | |||

According to the the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child, a child is defined as everyone under the age of 18 unless, "under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier"<ref name="United Nations, 1996">United Nations | |||

{{#ev:youtube|a0YdpvBzFYE}} | {{#ev:youtube|a0YdpvBzFYE}} | ||

== Definition, Incidence and Prevalence == | |||

[[File:Screen_Shot_2017-01-25_at_3.37.34_PM.png|right]] | |||

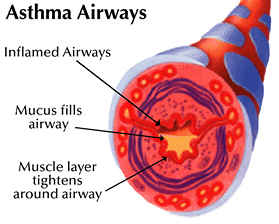

Asthma is an inflammatory disorder of the airways characterised by “paroxysmal or persistent symptoms such as [[Dyspnoea|dyspnea]], chest tightness, wheezing, [[sputum]] production and cough, associated with variable airflow limitation and a variable degree of hyperresponsiveness of airways to endogenous or exogenous stimuli”<ref name="Canadian Thoracic Society, 2010">Canadian Thoracic Society. Recommendations for the management of asthma hildren (6 years and over) and adults. http://www.respiratoryguidelines.ca/sites/all/files/cts_asthma_slim_jim_2010_final.pdf (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref>. | |||

Asthma is | [[Exercise Induced Asthma|Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB)]], is defined as the transient narrowing of the lower airways following exercise and is common among adolescents<ref name="Johannson et al. 2016">Johansson H, Norlander K, Janson C, Malinovschi A, Nordang L, Emtner M. The relationship between exercise induced bronchial obstruction and health related quality of life in female and male adolescents from a general population. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2016; 16(1): 1-9. Full version: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4847200/ (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref>. In the UK, approximately 1 in every 11 children are currently receiving treatment for asthma<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />. | ||

== Causes and Classification == | |||

According to the Asthma UK<ref>Asthma UK. Asthma facts and statistics 2016. https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/ (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>, there are different kinds of asthma triggers. For this resource, we have identified triggers that are more relevant to children:<br> | |||

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged between 2-5 years: | #Animals and pets | ||

#Colds and flu | |||

#Emotions | |||

#Food | |||

#House dust mites | |||

#Indoor environment | |||

#Mould and fungi | |||

#Pollen | |||

#Pollution | |||

#Smoking and second-hand smoke | |||

#[[Stress and Health|Stress and anxiety]] | |||

#Weather | |||

#Female hormones<br> | |||

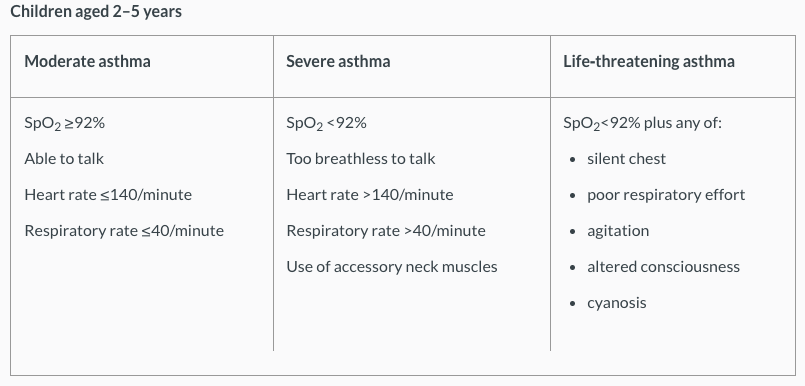

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged between 2-5 years<ref name="NICE quality statement 7">NICE. Quality statement 7: assessing severity. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25/chapter/quality-statement-7-assessing-severity (accessed 20 January 2017).</ref>. For more information, please refer [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25/chapter/quality-statement-7-assessing-severity here]: | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 12.53.26 AM.png]]<br> | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 12.53.26 AM.png]]<br> | ||

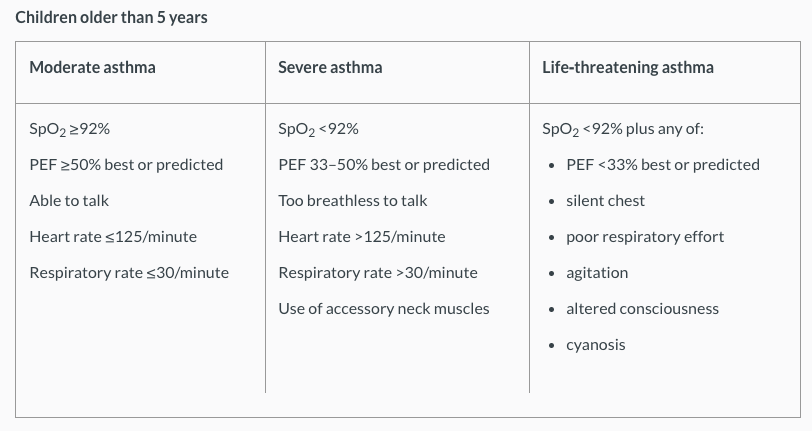

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged over 5 years<ref name="NICE quality statement 7" />. For more information, please refer [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25/chapter/quality-statement-7-assessing-severity here]: | |||

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged over 5 years | |||

[[Image: | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 12.53.38 AM.png]] | ||

=== Statistics === | |||

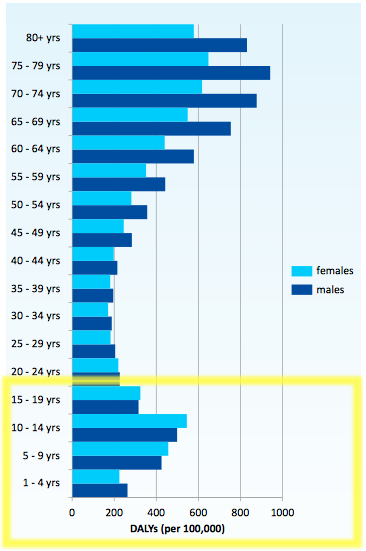

< | The figure below shows the burden of asthma in the global population in 2010<ref name="Global Asthma Network" />. This is measured by the [[Disability-Adjusted Life Year|disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)]], where the years of life prematurely lost and the years of life lived are added together. Specifically to children, the burden of asthma is shown to be greatest between 10-14 years. | ||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 2.20.06 PM.png]] | |||

<br> | Figure - Burden of disease, measured by disability adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 population attributed to asthma by age group and sex<ref name="Global Asthma Network">Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2014. http://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>.<br> | ||

< | According to the Asthma UK<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />: | ||

<br> | *The prevalence of childhood asthma in the UK is among the highest in the world. | ||

*Asthma is the most common chronic illness among children making up for 1 in 5 of all GP consultations. | |||

*On average, there are 3 children with asthma in every classroom with asthma. | |||

*A child is admitted to hospital due to an asthma attack every 20 minutes in the UK. | |||

*In Scotland, 368,000 people (1 in 14) are currently receiving treatment for asthma, amongst which 72,000 of them are children.<br> | |||

Developed by Asthma UK, the SAS visual analytical data can pull together information from locations all over the UK to see the prevalence rates, hospital admissions and percentage of the population in the UK that have asthma and actively seek treatment for this. Please click on the following link to access the Asthma UK analytic tool: [https://data.asthma.org.uk/SASVisualAnalyticsViewer/VisualAnalyticsViewer_guest.jsp?reportName=Asthma+UK+data+portal&reportPath=/Shared+Data/Guest/&reportViewOnly&_ga=1.38119331.106832277.1481754454 Asthma UK, SAS Visual Analytical Data] | |||

== Physical Activity == | |||

=== Definition, Incidence and Prevalence === | |||

[[ | The World Health Organization (WHO) defines [[Physical Activity|physical activity]] as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure”<ref name="WHO, 2016" />.<br> | ||

<br> | Children and adolescents aged 5-17 years old are recommended to do at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity daily, including muscle and bone [[Strength Training|strengthening]] activities at least 3 times a week<ref name="WHO, 2016" />. Even with the knowledge of the benefits of physical activity, the participation rate is reported to be insufficient worldwide. Globally, for adolescents that are aged 11-17 years old, it has been found that 81% of them were insufficiently physically active in 2010<ref name="WHO, 2016" />. In Scotland, the Scottish Health Survey in 2015 established that 27% of children aged 2-15 years did not meet the physical activity recommendations, which included school-based physical activity<ref name="Scottish Government, 2016">Scottish Government. Health of scotland’s population- physical activity. http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/TrendPhysicalActivity (accessed 3 October 2016).</ref>.<br> | ||

< | Children with asthma are generally less active than their healthy peers<ref name="Williams et al. 2008" />. A study found that children with asthma did an average daily physical activity of 116 minutes compared to that of healthy children of 146 minutes, and children with asthma only did less than 30 minutes of physical activity a day<ref name="Lang et al. 2004">Lang DM, Butz AM, Duggan AK, Serwint JR. Physical activity in urban school-aged children with asthma. Pediatrics 2004; 113(4): e341-6. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/113/4/e341.long (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref>. Children with moderate-to-severe asthma were also found to have lower physical activity levels than children with mild asthma<ref name="Lam et al. 2016">Lam K, Yang Y, Wang L, Chen S, Gau B, Chiang B. Physical activity in school-aged children with asthma in an urban city of Taiwan. Pediatrics and neonatology 2016; 57(4): 333-7. Full version: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875957215001916 (Accessed 6 October 2016).</ref>. | ||

=== Sedentary Behaviour === | |||

==== Definition, Incidence and Prevalence ==== | |||

The [[Sedentary Behaviour]] Research Network (SBRN) defines sedentary behaviour as “any waking activity with an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents and a sitting or reclining [[posture]]”<ref name="SBRN, 2016">SBRN. What is sedentary behaviour?. http://www.sedentarybehaviour.org/what-is-sedentary-behaviour / (accessed 5 October 2016).</ref>. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children and adolescents to reduce their sedentary behaviour to less than 2 hours per day<ref name="American College of Sports Medicine, 2014">American College of Sports Medicine. The 2014 united states report card on physical activity for children & youth. https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/other-documents/nationalreportcard_longform_final-for-web(2).pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed 10 November 2016).</ref>. | |||

The | |||

=== Statistics of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour === | === Statistics of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour === | ||

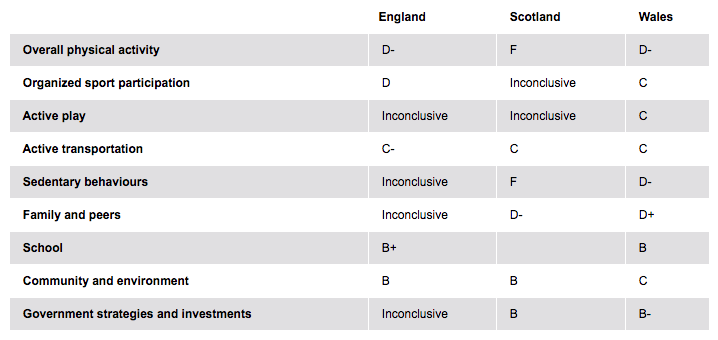

The table below compares physical activity in children between England, Scotland and Wales: | The table below compares physical activity in children between England, Scotland and Wales<ref name="Active Healthy Kids">Active Healthy Kids. The global matrix 2.0 on physical activity for children and youth. http://www.activehealthykids.org/ (accessed 12 January 2017).</ref>. Each category was scored using a grading system of A (highest grade) to F (lowest grade) and also inconclusive results. An A grade is classed as more than 80% of children and young people achieving this grade, a B grade is 60-79%, a C grade is 40-59%, a D grade is 20-39% and an F grade is less than 20% of children and young people achieving this grade: | ||

Children's activity across UK<ref name="Active Healthy Kids" />. For more information, please refer [http://www.activehealthykids.org/ here] | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-24 at 8.58.47 PM.png|x]]<br> | |||

=== Relationship Between Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Obesity in Children with Asthma === | === Relationship Between Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Obesity in Children with Asthma === | ||

Physical activity is essential for the normal growth and development of children and adolescents<ref name="Hills et al. 2007"> | Physical activity is essential for the normal growth and development of children and adolescents<ref name="Hills et al. 2007">Hills AP, King NA, Armstrong TP. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents. Sports Medicine 2007; 37(6): 533-45. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6328258_The_Contribution_of_Physical_Activity_and_Sedentary_Behaviours_to_the_Growth_and_Development_of_Children_and_Adolescents (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref><ref name="Hills et al. 2010">Hills AP, Okely AD, Buar LA. Addressing childhood obesity through increased physical activity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2010; 6(10): 543-49. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/45828143_Addressing_childhood_obesity_through_increased_physical_activity (accessed 14 November 2016).</ref><ref name="Hills et al. 2011" />. 60 minutes of physical activity a day has been shown to improve a child's cardiovascular and [[Bone|bone health]], improve their self-confidence and allow the development of new social and motor skills<ref name="Department of Health, 2011">Department of Health. Physical activity guidelines for children and young people (5-18 years). : https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/541231/CYP_infographic.pdf (accessed 10 November 2016).</ref><ref name="Longmuir et al. 2014">Longmiur PE, Colley RC, Wherley VA, Tremblay MS. Canadian society for exercise physiology position stand: benefit and risk for promoting childhood physical activity. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2014; 39(15): 1271-9. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/apnm-2014-0074 (accessed 6 October 2016).</ref>. It can reduce sedentary behaviour<ref name="Pearson et al. 2014">Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, Biddle SJH, Van Sluijs EMF, Atkin AJ. Associations between sedentary behaviour and physical activity in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews 2014; 15(8): 666-75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4282352/ (accessed 6 October 2016).</ref>, and is crucial in the prevention of becoming overweight and obese<ref name="Strong et al. 2005">Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJR, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, Hergenroeder AC, Must A, Nixon PA, Pivarnik JM, Rowland T, Trost S, Trudeau F. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. The Journal of Pediatrics 2005; 146(6): 732-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347605001009 (accessed 7 October 2016).</ref><ref name="Hills et al. 2011">Hills AP, Andersen LB, Byrne NM. Physical activity and obesity in children. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011; 45(11): 866-70. http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/45/11/866.full.pdf+html (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref>. It can also contribute to present, future health and wellness by imprinting healthy behaviour habits and reducing the risk of future [[Chronic Disease|chronic diseas]]<nowiki/>e<ref name="Longmuir et al. 2014" />. | ||

<br>There is evidence to | <br>There is evidence to suggest that physical activity can improve the asthmatic child’s aerobic and anaerobic fitness<ref name="Strong et al. 2005" />. Physical activity engagement can also reduce the amount of school absences and GP appointments, reduce the strength or dose of medication taken<ref name="Welsh et al. .2005">Welsh L, Kemp JP, Roberts RGD. Effects of physical conditioning on children and adolescents with asthma. Sports Medicine 2005; 35(2): 127-41. http://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00007256-200535020-00003 (accessed 15 October 2016).</ref>, and improve the child’s ability to cope with asthma<ref name="van Veldhoven et al. 2001">Van Veldhoven NHMJ, Vermeer A, Bogaard JM, Hessels MGP, Wijnroks L, Collard VT, Van Essen-Zandvliet EEM. Children with asthma and physical exercise: effects of an exercise programme. Clinical Rehabilitation 2001; 15(4): 360-70. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11828125_Children_with_asthma_and_physical_exercise_Effects_of_an_exercise_programme (accessed 4 October 2016).</ref>.<br> | ||

=== Impact of Asthma on Physical Activity Using the ICF Model === | |||

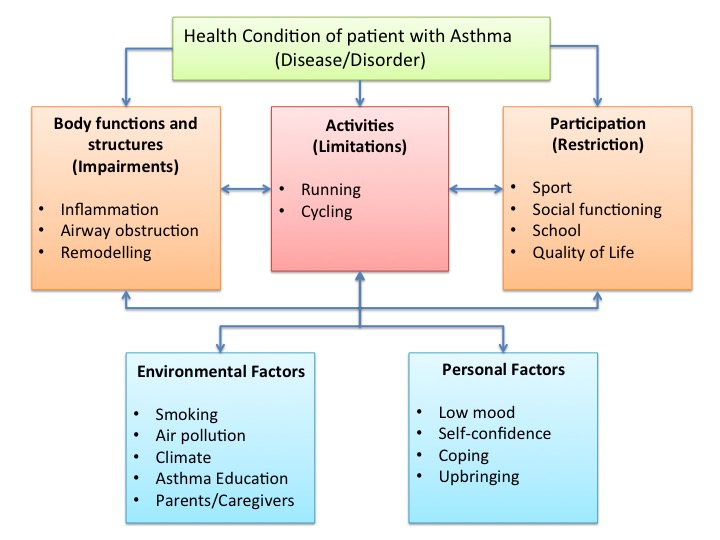

= | The [[International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)|International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health]] (ICF) model is a classification of health and health-related domains and describes how people live with their health condition<ref name="WHO, 2002">World Health Organisation. Towards a common language for functioning disability and health: ICF World Health Organization 2002. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf (assessed 4 October 2016).</ref>. According to the ICF, asthma can influence participation of the child in areas such as sport, school activities, social impact and [[Quality of Life|quality of life]]<ref>Van Gent R, Van Essen-Zandvliet EEM, Klijn P, Brackel HJL, Kimpen JLL, Van Der Ent CK. Participation in daily life of children with asthma. Journal of Asthma 2008; 45(9): 807-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18972300 (Accessed 10 October 2016).</ref>. Personal and environmental factors, such as their parents and asthma education, can also play a role in how children with asthma function.<br> | ||

[[Image:Slide1.jpg|ICF Model]] | |||

=== Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity === | |||

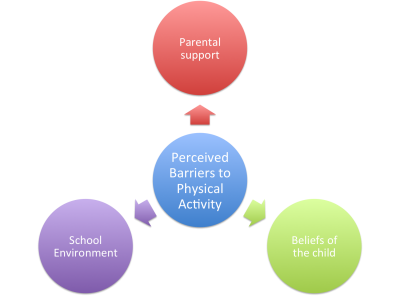

<br> | [[Image:BarriesToExerciseFINAL.png|right|400x300px]]There are 3 main perceived barriers that affect children with asthma. These barriers are involved with the inability to complete or take part in physical activity. The barriers are parental support, beliefs of the child and school environment.<br> | ||

==== Parental Support ==== | |||

Parental activity-related support has the ability to influence a child’s physical activity levels<ref name="Gustafson and Rhodes, 2006">Gustafson SL, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Medicine 2006; 36(1): 79-97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16445312 (Accessed 6 October 2016).</ref>. A study completed in 2004 showed that roughly 1 in 5 parents agree that exercise is harmful for children with asthma, and 1 in 4 parents are afraid that exercise would cause their child to fall ill or increase their symptoms<ref name="Lang et al. 2004" />. It is established that 37% of mothers imposed restrictions to their children’s physical activity levels due to negative beliefs towards asthmatics taking part in physical activity; the mother's negative perception of children’s dyspnea after running on a treadmill and children’s asthma severity<ref name="Dantas et al. 2014">Dantas FM, Correia MA, Silva AR, Peixoto DM, Sarinho ES, Rizzo JA. Mothers impose physical activity restrictions on their asthmatic children and adolescents: an analytical cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014; 14(1): 287-94. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-287 (accessed 14 December 2016).</ref> are also impacted.<br> | |||

==== Beliefs of the Child ==== | |||

<div> | |||

=== | Many children with asthma believe that limitations on their activity, whether it be at school or with sporting activities such as football or swimming, are an inevitable part of having asthma<ref name="Callery et al. 2003">Callery P, Milnes L, Verduyn C, Couriel J. Qualitative study of young people’s and parents’ beliefs about childhood asthma 2003; 53(488): 185-90. Full version: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1314542/pdf/14694693.pdf (Accessed 6 october 2016).</ref>. A study also suggested that the desire to meet socially defined forms of normality, thereby maintaining membership of a valued social group<ref name="Williams et al. 2008" />. This avoids stigma as "social exclusion” appears to be an important factor affecting the participation of physical activity in children with asthma. This may result in low levels of self-efficacy, especially when physical activity engagement is valued amongst their peers. | ||

</div> | |||

< | |||

==== School Environment ==== | |||

<div> | <div> | ||

Studies have shown that a major problem for teachers was differentiating between the normal consequence of exertion from physical activity and breathlessness due to their asthma<ref name="Williams et al. 2010">Williams B, Hoskins G, Pow J, Neville R, Mukhopadhyay S, Coyle J. Low exercise among children with asthma: a culture of over protection? a qualitative study of experiences and beliefs. British Journal of General Practice 2010; 60(577): e319-26. Full version: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913757/pdf/bjgp60-e319.pdf (Accessed 11 October 2016).</ref>. Children may be more likely to be asked to not take part in physical activity at school, so as to reduce the risk of an asthma exacerbation. This then encourages children with asthma not to participate in physical activity. Hence, it is important for school teachers to learn to recognise the correct signs and symptoms, in order to provide better management for the child’s condition and to not send the wrong message to the child with regards to their activity participation. | |||

Studies have shown that a major problem for teachers | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Current Policies to Asthma Management == | ||

=== Asthma UK === | === Asthma UK === | ||

[https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/understanding-asthma/ Asthma UK] is organisation whose goals are to raise awareness of asthma and to support children | [https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/understanding-asthma/ Asthma UK] is an organisation whose goals are to raise awareness of asthma and to support children who have asthma. Their ultimate objective is to raise funding for asthma research, to potentially find a cure for asthma and to fund new innovations to aid with the treatment of asthma. | ||

Asthma UK advocates the benefits of exercise in children with asthma and | Asthma UK advocates the benefits of exercise in children with asthma and recommends that they spend at least 1 hour a day doing some form of physical activity. The organisation feels that as long as the child is managing their asthma well and is actively taking their medication, exercise will benefit them and hopefully improve their confidence about their condition<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />. | ||

While | While Asthma UK has clear guidelines on what to do if a child has an asthma attack and how to handle it, they offer no clear guidance on the intensity or timing of exercise in children with asthma . This is an area of research that would greatly benefit physiotherapists in dealing with paediatric patients, as it will allow them to design an exercise regime and treatment plan which is supported by relevant evidence. This is an area in which the foundation could provide future research and funding, especially as [[obesity]] in children has become an increasing problem in Britain<ref name="Dehghan et al. 2005">Dehghan M, Akhtar-Danesh N, Merchant AT. Childhood obesity, prevalence and prevention. Nutrition journal 2005; 4(24): 24-32. http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/770/art%253A10.1186%252F1475-2891-4-24.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fnutritionj.biomedcentral.com%2Farticle%2F10.1186%2F1475-2891-4-24&token2=exp=1485466280~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F770%2Fart%25253A10.1186%25252F1475-2891-4-24.pdf*~hmac=cef9d736f6141e3f81c3448a8d87297eb356c8a46f039bc13d86a6c40525d70a (accessed 4 January 2017).</ref>. | ||

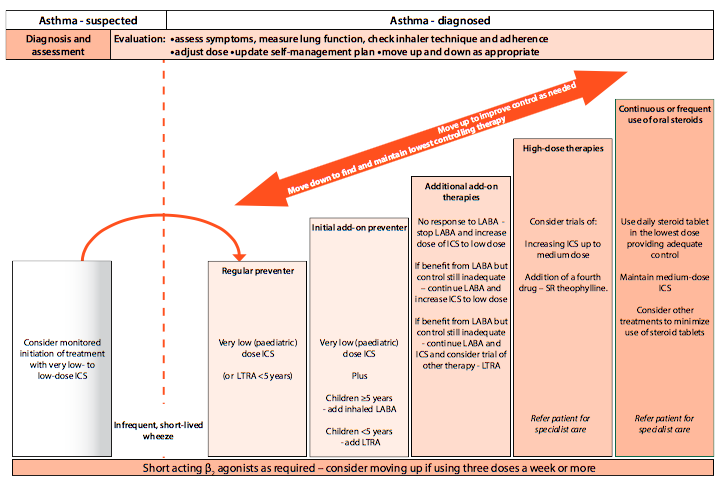

=== Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) === | === Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) === | ||

While the [https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/ SIGN guidelines] provide similar information on what to do in case of an asthma attack, there is little focus on addressing the efficacy and effectiveness of physical exercise in children with asthma. There is a larger emphasis placed on the medical aspect of asthma management and allergen avoidance. In the SIGN guidelines for management of asthma | While the [https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/ SIGN guidelines] provide similar information on what to do in case of an asthma attack, there is little focus on addressing the efficacy and effectiveness of physical exercise in children with asthma. There is a larger emphasis placed on the medical aspect of asthma management and allergen avoidance. In the SIGN guidelines for management of asthma<ref name="SIGN 2016" />, there is only a short mention of improving dietary intake and incorporating exercise-based interventions. However, this is in relation to weight loss in children and not as a health management strategy in unison with medical management, regardless of the child's weight factors. | ||

This guideline in particular is focused almost entirely on the medical approach to managing symptoms. More specifically, in the section of the guideline concerning what a parent can do to help manage their child’s asthma, only the following | This guideline in particular is focused almost entirely on the medical approach to managing symptoms. More specifically, in the section of the guideline concerning what a parent can do to help manage their child’s asthma, only the following 3 instructions are mentioned<ref name="SIGN, 2014">SIGN. Managing asthma in children: a booklet for patients and their families and carers october 2014. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/pat141_CHILDREN.pdf (accessed 28 December 2016).</ref>: | ||

*Making sure the child takes their asthma medication when they should | *Making sure the child takes their asthma medication when they should | ||

*Avoiding exposure of the child to cigarette smoke | *Avoiding exposure of the child to cigarette smoke | ||

*Encouraging the child to lose weight if necessary<ref name="SIGN | *Encouraging the child to lose weight if necessary<br> | ||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 12.40.11 AM.png]]<ref name="SIGN 2016">SIGN. BTS/SIGN British guideline on the management of asthma 2016. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/btssign-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma/ (accessed 28 December 2016).</ref><br> | |||

=== National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) === | |||

[https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25/chapter/Introduction-and-overview NICE (2016a)] state that there is no specific exercise plan for children who have asthma, and offer no time frame or intensity of the amount of exercise a child should do. They say it is appropriate to advise these patients regarding the precautions of exercise-induced asthma and how to manage this<ref name="NICE, 2016">NICE. Management of exercise induced asthma 2016. http://cks.nice.org.uk/asthma#!scenario:4 (accessed 28 December 2016).</ref>. Again, this is an area in which the NICE guidelines could seek to improve on, by developing guidelines on the recommended timing and intensity of exercise for children with asthma. | |||

== | == The Role of Physiotherapy == | ||

Physiotherapists have a wide intervention scope for children with asthma, however, numerous newly-qualified physiotherapists are unaware of their extensive role in the management of respiratory conditions in children.<br> | |||

Physiotherapists have a wide intervention scope for children with asthma however numerous newly-qualified physiotherapists are unaware of their extensive role | |||

=== Subjective Assessment === | === Subjective Assessment === | ||

A diagnosis of asthma can be | A diagnosis of asthma can be confirmed based on various factors and symptoms. The child will be asked to explain the various symptoms, but it is also important to hear the parents' interpretation of the child's symptoms. You should ask the child to describe the frequency, duration and aggravating factors of their symptoms. It is important as a physiotherapist to know if they have been exposed to triggers as listed above in the resource as this might lead to the onset of asthmatic symptoms. It is also helpful to ask if there is any family history of asthma or allergies as this makes the child more likely to be suffering from asthmatic symptoms. While there is an increased risk of children having asthma if there is a family link, it is believed that over 100 genes may be related to asthma. However, the risk of the individual effect of any one of these genes is quite small. Research is still being conducted to establish the genetic link in hereditary asthma<ref name="Ober and Hoffjan, 2006">Ober C, Hoffjan S. Asthma genetics: The long and winding road to gene discovery. Genes and Immunity 2006;7:2:95-100.</ref>. | ||

==== Symptoms ==== | ==== Symptoms ==== | ||

While carrying out a subjective assessment for a child with asthma, it is important to understand the child’s opinion on his/her symptoms, the severity if they are able to communicate and the parent or guardians view on their symptoms. | |||

* Frequent, intermittent coughing – Children can have a persistent cough with an intermittent onset. If noticed by a parent It should be investigated. The child can also suffer from bouts of coughing which get worse when the child has respiratory [[Infection control|infection]]<ref name="Rubin et al. 1998.">Rubin BK, Newhouse MT, Barnes PJ. Conquering childhood asthma: An illustrated guide to understanding the treatment and control of childhood asthma. First Edition. Hamilton, Ontario: Empowering Press.</ref>. | |||

Frequent, intermittent coughing – Children can have a persistent cough with an intermittent onset. If noticed by a parent It should be investigated. The child can also suffer from bouts of coughing which get worse when the child has respiratory infection<ref name="Rubin et al. 1998."> | * Wheezing sound when exhaling – Children often present with a wheezing sound on exhalation. This is a strong indication of asthma that may persist throughout childhood and adult life<ref name="Sears et al. 2003">Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, Wiecek EM, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Herbison GP, Silva PA, Poulton R. A longitudinal, population based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine 2003;349:15:1414-22.</ref>. | ||

* Shortness of Breath – Struggling for breath even at rest and low levels of activity can be a symptom of asthma in children. Heavy and harsh breathing sounds are symptoms parents should look out for. | |||

* Fatigue – Asthma can cause children to sleep poorly, this can cause children to appear tired during the day even after having a full night’s sleep. This can affect performance and behaviour in school as well<ref name="Fagnano et al. 2011">Fagnano M, Bayer AL, Isensee CA, Hernandez T, Halterman JS. Nocturnal asthma symptoms and poor sleep quality amoung urban school children with asthma. Academic Pediatrics 2011;11:6:493-99.</ref>. | |||

* Chest pain & tightness – Chest pain is particularly prevalent in younger children with asthma. Chest tightness can be accompanied by shortness of breath<ref name="Anas, 2007">Anas NG. Pediatric hospital medicine: Textbook of inpatient management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer Health and Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2007.</ref>. | |||

=== Objective Assessment === | === Objective Assessment === | ||

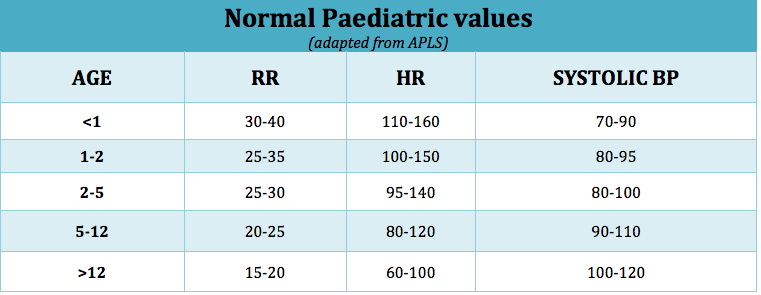

==== Vital signs | ==== Vital signs ==== | ||

[[Vital Signs|Vital signs]] include: | |||

#Heart rate (HR) | #Heart rate (HR) | ||

#Blood pressure (BP) | #Blood pressure (BP) | ||

#Respiratory rate (RR) | #Respiratory rate (RR) | ||

#Oxygen saturation (SpO2) | #Oxygen saturation (SpO2) | ||

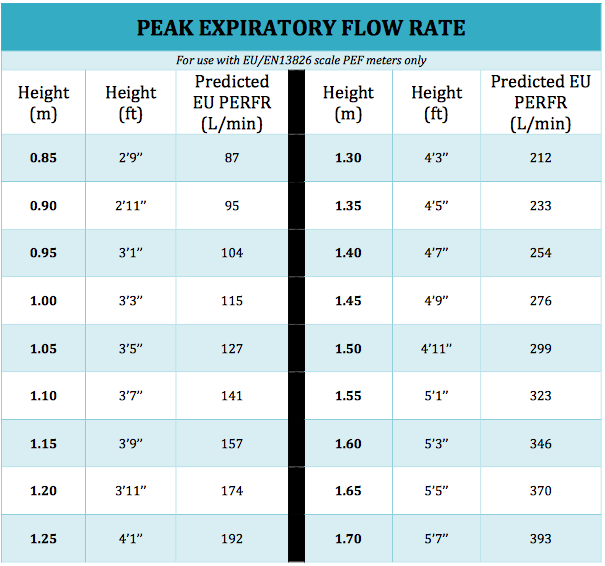

#Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) | #Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF)<br> | ||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 12.25.01 AM.png|x]] | |||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 12.25.01 AM.png|x]] | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 12.15.03 AM.png|x]]<br> | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 12.15.03 AM.png|x]]<br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|055fSYXgNKU }} | |||

{{#ev:youtube|055fSYXgNKU }} | |||

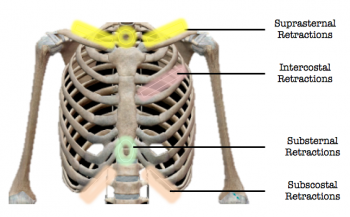

==== Inspection ==== | ==== Inspection ==== | ||

| Line 466: | Line 171: | ||

'''General appearance''' | '''General appearance''' | ||

#Posture | #[[Posture]] | ||

#*Sitting upright or tripod position | |||

#Nasal flaring | #Nasal flaring | ||

#Breathlessness in speech (assessing if the child can complete sentences in | #Breathlessness in speech (assessing if the child can complete sentences in 1 breath) | ||

#Cyanosis | #[[Cyanosis]] | ||

'''Breathing''' | '''Breathing''' | ||

| Line 475: | Line 181: | ||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 6.05.46 PM.png|right|350x225px]] | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-25 at 6.05.46 PM.png|right|350x225px]] | ||

#Retractions: Indrawing of skin | #Chest Retractions: Indrawing of skin | ||

#Use of accessory muscles | #*Suprasternal (Tracheal tug): Middle of neck above sternum | ||

#*Substernal: Abdomen below sternum | |||

#*Intercostal: Skin between each rib | |||

#*Subcostal: Abdomen below [[Ribs|rib cage]] | |||

#*Supraclavicular: Neck above collarbone<br><br> | |||

#Use of accessory muscles | |||

#*[[Sternocleidomastoid]] | |||

#*Parasternal | |||

#*[[Scalene]] | |||

#*[[Trapezius]] | |||

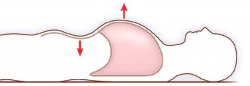

#Thoracic/Shallow breathing | #Thoracic/Shallow breathing | ||

#Paradoxical chest wall movement: Inward movement on inspiration and outward movement on expiration<br> | #Paradoxical chest wall movement: Inward movement on inspiration and outward movement on expiration<br> | ||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 1.16.48 AM.png|250x100px]] | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 1.16.48 AM.png|250x100px]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 490: | Line 203: | ||

#Barrel-shaped | #Barrel-shaped | ||

#Anteroposterior diameter (May increase due to hyperinflation) | #Anteroposterior diameter (May increase due to hyperinflation) | ||

'''Cough''' | '''Cough and sputum''' | ||

#Usually nonproductive accompanied by wheezing | |||

#Sputum may progress to expectoration of viscous, mucoid sputum which is difficult to clear<br><br> | |||

==== Palpation ==== | ==== Palpation ==== | ||

| Line 506: | Line 218: | ||

'''Symmetry of chest movement''' | '''Symmetry of chest movement''' | ||

<br> | To test the symmetry of chest movement, have the child seated erect or stand with their arms by their side. Stand behind child and hold the lower hemithorax on either side of axilla and gently bring your thumbs to the midline. Have the child slowly take a deep breath in and expire. Watch the symmetry of movement of the hemithorax. Simultaneously, feel the chest expansion. Place your hands over upper chest and apex and repeat the process. Next, stand in front of the child and lay your hands over both apices of the [[Lung Anatomy|lung]] and anterior chest and assess chest expansion.<br> | ||

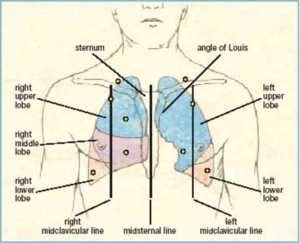

==== Auscultation | ==== [[Auscultation]] ==== | ||

'''Lung fields''' | '''Lung fields''' | ||

#Right anterior lung field (RUL & RML) | #[[File:Screen_Shot_2017-01-25_at_12.49.44_AM.png|right|300x300px]]Right anterior lung field (RUL & RML) | ||

#Right posterior lung field (RUL & RLL) | #Right posterior lung field (RUL & RLL) | ||

#Left anterior lung field (LUL & LLL) | #Left anterior lung field (LUL & LLL) | ||

#Left posterior lung field (LUL & LLL)<br> | #Left posterior lung field (LUL & LLL)<br> | ||

<br>'''Wheezing''' | <br>'''Wheezing''' | ||

High-pitched, widespread<br>To hear what a wheeze sounds like, please refer [http://www.easyauscultation.com/wheezing here] | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

=== Asthma Control Test (ACT) === | |||

The [https://www.asthma.com/content/dam/NA_Pharma/Country/US/Unbranded/Consumer/Common/Images/MPY/documents/80108R0_AsthmaControlTest_ICAD.pdf ACT] was developed as a tool to identify patients with poorly controlled asthma. It is a short, simple questionnaire that patients can do themselves to identify if their asthma may be poorly controlled. The questionnaire is age specific as they have a questionnaire with facial expressions aimed at | The [https://www.asthma.com/content/dam/NA_Pharma/Country/US/Unbranded/Consumer/Common/Images/MPY/documents/80108R0_AsthmaControlTest_ICAD.pdf ACT] was developed as a tool to identify patients with poorly controlled asthma. It is a short, simple questionnaire that patients can do themselves to identify if their asthma may be poorly controlled. The questionnaire is age-specific as they have a questionnaire with facial expressions aimed at children aged 4-11 which makes it easier for them to identify their symptoms. Another asthma control test is aimed at children aged 12 years and older. A score of 19 or less identifies patients with poorly controlled asthma. The ACT has been shown to be reliable and responsive to changes in asthma management in patients<ref name="Kennedy and Jones, 2007">Kennedy J, Jones SM. Asthma control test: Reliability, validity and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. Paediatrics 2007;120:132-3.</ref>.<br> | ||

=== Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children (PAQ-C) and Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAR-A) === | |||

The PAQ-C and the PAQ-A are validated self-report measures of physical activity widely used to assess physical activity in children aged 8-14 and 14-20 respectively<ref name="Kowalski et al. 2005" | The PAQ-C and the PAQ-A are validated self-report measures of physical activity widely used to assess physical activity in children aged 8-14 and 14-20 respectively<ref name="Kowalski et al. 2005" />. Both and PAR-C and PAQ-A are self-administered tests, measuring general moderate to vigorous physical activity levels. It is a low cost, reliable and valid assessment of physical activity from childhood through adolescence<ref name="Kowalski et al. 2005">Kowalski KC, Crocker PRE, Donen RM. The physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) and adolescents (PAQ-A) manual. http://www.hfsf.org/uploads/Physical%20Activity%20Questionnaire%20Manual.pdf (accessed 2 January 2017).</ref>.<br> | ||

=== Paediatric Asthma Quality of life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) === | |||

The PAQLQ is a health-related quality of life assessment that can provide an idea of the functional impairments (Physical, emotional and social) of the paediatric patient that are important to the patients in their everyday lives<ref name="Juniper et al. 1997" | The PAQLQ is a health-related quality of life assessment that can provide an idea of the functional impairments (Physical, emotional and social) of the paediatric patient that are important to the patients in their everyday lives<ref name="Juniper et al. 1997" />. The Paediatric Asthma Quality of life questionnaire (PAQLQ) is targeted at children aged 7-17 years and has 23 questions in 3 areas (Symptoms, activity limitation and emotional function). The activity domain contains ‘patient-specific’ questions. Children are asked to think about how they have been during the previous week and to respond to each of the 32 questions on a 7-point scale (7= not bothered at all- 1= extremely bothered)<ref name="Juniper et al. 1997" />. Calculation of the results involves taking the mean of all the 23 responses and the individual domain scores are the means of the items in those domains<ref name="Juniper et al. 1997">Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Griffith LE, Ferrie PJ. Minimum skills required by children to complete health-related quality of life instruments for asthma: Comparison of measurement properties. European Respiratory Journal 1997;10:10:2285-95. http://erj.ersjournals.com/content/10/10/2285.long (accessed 3 January 2017).</ref>. For information, please refer [https://www.qoltech.co.uk/obtaining.html here] | ||

=== Dalhousie Dyspnea and Perceived Exertion Scale === | |||

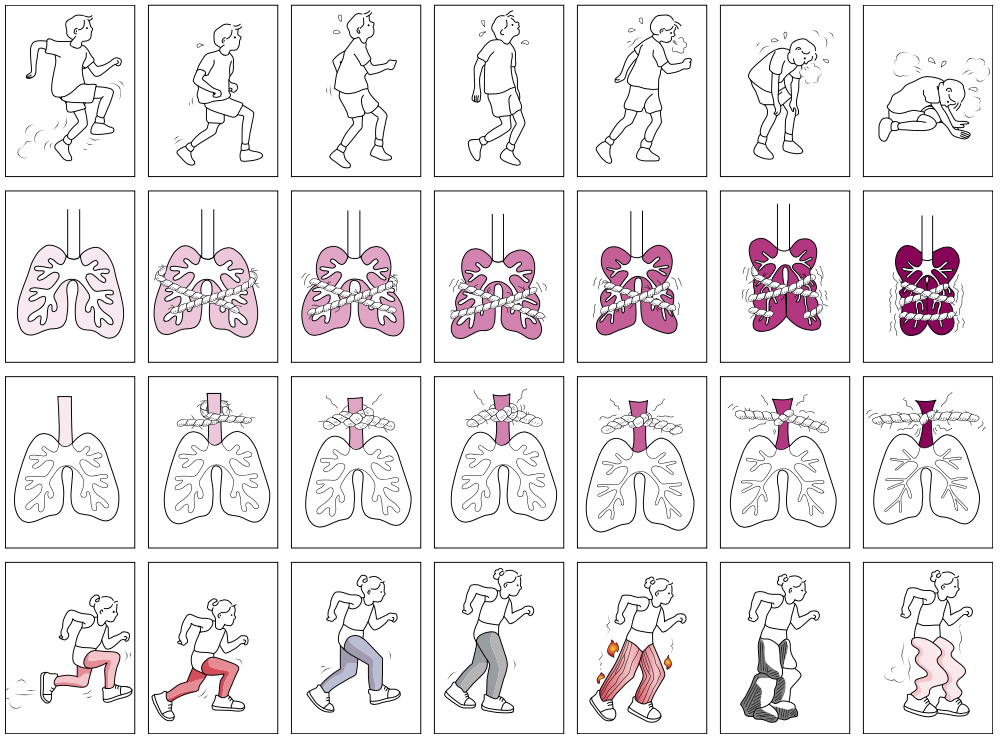

===== Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale | The Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale is a pictorial scale that encompasses the full range of the perception of breathlessness by children<ref name="McGrath et al. 2005">McGrath PJ, Pianosi PT, Unruh AM, Buckley, CP. Dalhousie dyspnea scales: Construct and content validity of pictoriall scales for measuring dyspnea. BMC Pediatrics 2005;5:1:1-7. http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/857/art%253A10.1186%252F1471-2431-5-33.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fbmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com%2Farticle%2F10.1186%2F1471-2431-5-33&token2=exp=1485523512~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F857%2Fart%25253A10.1186%25252F1471-2431-5-33.pdf*~hmac=ddf216625707d441b4155efbb4c5e6c1b26ab8df4c62e535f0273c921de9e7f0 (accessed 2 January 2017).</ref>. Areas tested: | ||

* Breathing effort | |||

* Chest tightness | |||

* Throat closure<br><br>The image below shows 7 pictures that are used with increasing severity in each series<ref name="Pianosi et al. 2015">Pianosi PT, Huebner M, Zhang Z, Turchetta A, McGrath PJ. Dalhousie pictorial scales measuring Dyspnea and perceived exertion during exercise for children and adolescents. American Thoracic Society 2015;12:5:718-26. http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-477OC (accessed 5 January 2017).</ref>. This scale has been validated against the Perceived Exertion Scale in children 7 years or older with asthma or cystic fibrosis.<ref name="McGrath et al. 2005" /> | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-20 at 3.15.00 PM.png]]<br> | |||

=== Paediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM) === | |||

[ | The [http://www.chu-sainte-justine.org/childasthmatools/en/pdf/scorepram_en.pdf PRAM] is a valid and reliable objective assessment of asthma severity for children aged 2-17 years with acute asthma<ref name="Ducharme et al. 2008" />. It is tested on a 12-point scale for 5 different areas (Oxygen saturation, suprasternal retraction, scalene muscle contraction, air entry and wheezing)<ref name="Ducharme et al. 2008">Ducharme FM, Chalut D, Plotnick L, Savdie C, Kudirka D, Zhang X, Meng L, Mcgillivray D. The pediatric respiratory assessment measure: A valid clinical score for assessing acute asthma severity from toddlers to teenagers. The Journal of Pediatrics 2008;10.1016:476–480. http://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(07)00786-X/pdf (accessed 15 Jan 2017).</ref>. | ||

3-hour PRAM scores can be used in clinical settings to facilitate the decision to admit or initiate more aggressive adjunctive therapy to decrease the need for hospitalisation<ref name="Alnaji et al. 2014">Alnaji F, Zemek R, Barrowman N, Plint A. PRAM score as predictor of pediatric asthma hospitalization. Academic Emergency Medicine 2014; 10.111:872–878. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.12422/epdf (accessed 12 Jan 2017).</ref>. | |||

== Physiotherapy Management == | |||

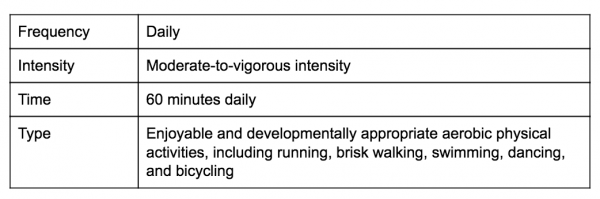

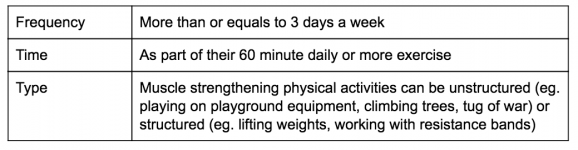

=== | === Exercise Prescription === | ||

According to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), children are required to partake in aerobic exercises, muscle strengthening and bone strengthening exercises<ref name="Wilkins, 2013" />. These exercises are classified according to Frequency, Intensity, Time and Type of physical activity as shown in the tables below: | |||

==== Aerobic Exercise ==== | |||

[[FITT Principle|FITT]] for aerobic exercise for healthy children<ref name="Wilkins, 2013" /> | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 3.20.17 PM.png|600x215px]] | |||

==== Muscle Strengthening ==== | |||

FITT for muscle strengthening for healthy children<ref name="Wilkins, 2013" /> | |||

[[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 3.20.24 PM.png|600x150px]] | |||

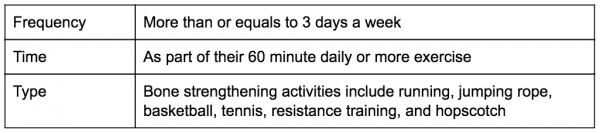

==== Bone Strengthening ==== | |||

FITT for bone strengthening for healthy children<ref name="Wilkins, 2013">Wilkins LW . ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and prescription, 9th ed. + essential clinical. United States: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2013.</ref> | |||

[[Image: | [[Image:Screen Shot 2017-01-26 at 3.20.40 PM.png|600x150px]] | ||

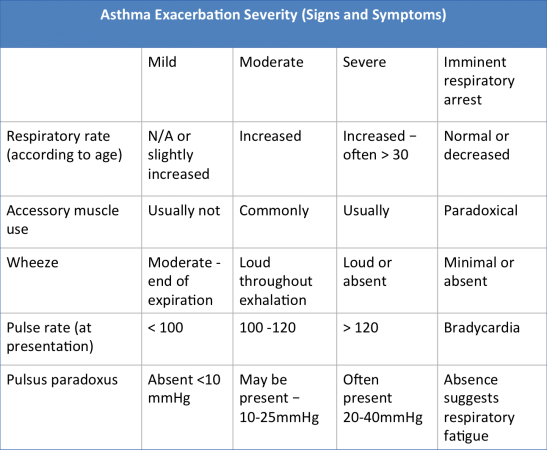

=== Effective Management of Exacerbations === | |||

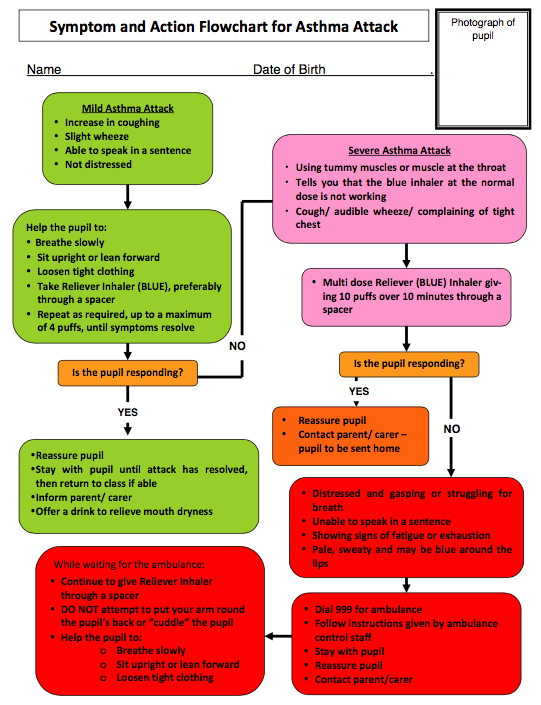

= | Asthma exacerbations in children can be categorised according to its severity. The table below can be useful for the physiotherapist to identify the severity of asthma via signs and symptoms<ref name="Kumar, 2014">Kumar R. Asthma exacerbation Severity. http://www.slideshare.net/RakeshKumar235/management-of-acute-severe-asthma (accessed 7 January 2017).</ref>.<br> | ||

[[Image:Asthma table signs and symptoms.png|600x450px]] | |||

=== Patient Education and Self-management === | |||

Asthma education for children can promote active involvement and facilitation of learning from other’s shared experiences, leading to improved confidence in their own strength and empowerment, as well as their sense of coherence (SOC) in managing their own condition<ref name="Trollvik et al. 2013">Trollvik A, Ringsberg KC, Silén C. Children’s experiences of a participation approach to asthma education. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2013;22:996–1004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23311685 (acessed 10 Jan 2017).</ref>. Studies suggest that physical activity improves cardiopulmonary function without compromising lung function and does not have an adverse effect on wheeze for children with asthma<ref name="Ram et al. 2005">Ram FSF, Robinson SM, Black PN, Picot J. Physical training for asthma (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD001116</ref>. Thus, respiratory education for the child which includes secretion clearance techniques, strengthening of the respiratory muscles and specifically timed inspirations and expirations can act as exacerbation preventative therapy<ref name="Valdivia, 2008">Teaching children to breathe: respiratory education is healing and preventive. Full version: http://fundrogertorne.org/health-childhood-environmental/2009/01/08/teaching-children-to-breathe-respiratory-education-is-healing-and-preventive (accessed 8 Jan 2017).</ref>. | |||

However, educating the child with asthma about the feasibility and benefits of physical activity will not be effective if the family and school contexts are not also persuaded to encourage and facilitate participation<ref name="Coleman et al. 2001">Coleman H, McCann DC, McWhirter J, Calvert M, Warner JO. Asthma, wheeze and cough in 7- to 9-year-old British schoolchildren. Ambulatory Child Health 2001;7:313–21. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1467-0658.2001.00140.x/abstract (accessed 14 Jan 2017).</ref><ref name="Williams et al. 2008">Williams B, Powell A, Hoskins G, Neville R. Exploring and explaining low participation in physical activity among children and young people with asthma: A review. BMC Family Practice 2008; 9(1): 40-51. Full version: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2447841/pdf/1471-2296-9-40.pdf (Accessed 11 October 2016).</ref>. Parents and teachers also need to be educated on how and when children with asthma<ref>Mansour ME, Lanphear BP, DeWitt TG. Barriers to asthma care in urban children: Parent perspectives. Pediatrics 2000;106:512–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10969096 (accessed 2 Jan 2017)</ref> can participate in physical activity, how to adjust medication before and during periods of extended activity and how to differentiate between limitations at times of asthma exacerbation and overall limitations. There is evidence to show that although medical advice were frequently cited by children and parents to explain reduced activity participation, it was in fact their beliefs about the capability of the child to manage the symptoms, safety of the physical activity and motivation of the child that most strongly influenced the child’s desire to take part in physical activity and their parents’ support<ref name="Mansour et al. 2000">Villa F, Castro APBM, Pastorino AC, Santarem JM, Martins MA, Jacob CMA, Carvalho CR. Aerobic capacity and skeletal muscle function in children with asthma. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2011;23:554–9. http://adc.bmj.com/content/96/6/554.full.pdf+html (accessed 5 Jan 2017).</ref>. Therefore, asthma education should be delivered to the child, their family and their school, especially for physical activity participation.<br> | |||

==== Airway Clearance Techniques ==== | |||

= | Airway mucus plugging has long been recognized as a principal cause of death in asthma<ref name="Evans et al. 2009">Evans CM, Kim K, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Mucus Hypersecretion in Asthma: Causes and Effects. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2009; 15(1): 4-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709596/ (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. Airway Clearance Techniques are indicated for individuals whose ability to mobilise and expectorate airway secretions is compromised due to altered cough mechanics or problems with the function of their mucociliary escalator or both<ref name="Volsko 2013">Volsko T. Airway Clearance Therapy: Finding the Evidence. Respiratory Care. 2013;58(10):1669-1678. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24064626 (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. These techniques are not recommended during an acute asthma exacerbation but can be trialed in the sub-acute phase if there are secretion clearance issues to be addressed. Some examples of airway clearance techniques are: Active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) and positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy<ref>Ontario Lung Association. Primary Care Asthma Program. http://www.on.lung.ca/document.doc?id=2497 (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. | ||

The ACBT is an active breathing technique performed by the patient to help clear sputum in the lungs. The 3 main phases are:<br>1. Breathing control<br>2. Deep breathing exercises/ thoracic expansion exercises<br>3. Huffing/ forced expiratory technique (FET) | |||

PEP creates pressure in the lungs and keeps the airways from closing. The air flowing through the PEP device helps move the mucus into the larger airway. A huff will help move the mucus out of the airways. | |||

'''<br>Bubble PEP''' | |||

==== Breathing | The Bubble PEP is a treatment for young children (at least 3 years) who may have a build-up of secretion in their lungs and have difficulty clearing it. The child is encouraged to blow down the tubing into the water and make bubbles. This creates positive pressure back up the tubing and into the child's airways and lungs. The positive pressure opens the child's airways, and helps air to move in and out of the lungs, which moves secretions out of the lungs and clears the patient's airways<ref>NHS Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. Bubble PEP. http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/medical-information-0/procedures-and-treatments/bubble-pep (accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>. For more information, please refer [http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/medical-information-0/procedures-and-treatments/bubble-pep here]<br> | ||

==== Breathing Techniques ==== | |||

A common sign of poorly managed asthma in children is superficial/clavicular breathing. In this type of breathing, expansion of the chest only occurs around the height of the clavicles upon inspiration, the neck muscles pull the first 2 ribs in an upward direction and the diaphragm and abdomen hardly intervene. The inefficiency of this breathing pattern due to its high energy expenditure for minimal gaseous exchange makes it a perfect starting point for respiratory education to introduce lateral, deeper breathing. | A common sign of poorly managed asthma in children is superficial/clavicular breathing. In this type of breathing, expansion of the chest only occurs around the height of the clavicles upon inspiration, the neck muscles pull the first 2 ribs in an upward direction and the diaphragm and abdomen hardly intervene. The inefficiency of this breathing pattern due to its high energy expenditure for minimal gaseous exchange makes it a perfect starting point for respiratory education to introduce lateral, deeper breathing. | ||

Studies suggest that cardiovascular endurance conditioning should be the key aspect of the physical activity a child with asthma receives<ref name="Villa et al. 2011">Villa F, Pastorina A C, Santarém j M, Marina M A, Jacob C M A, Carvalho C R, Castro A P B M. Aerobic Capacity and Skeletal Muscle Function in Children with Asthma. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011; 96(6): 554-9. http://adc.bmj.com/content/96/6/554.full.pdf+htm (accessed 8 January 2017).</ref>. Respiratory exercises enhance exercise tolerance and help build resistance against muscle fatigue. Balloon blowing; cotton-wool straw football exercises are excellent examples of games which are fun for children and simultaneously increase lung volume and improve gaseous exchange to improve quality of life in a relatively controlled manner<ref name="Thomas et al. 2009">Thomas M, McKinley RK, Mellor S, Watkin G, Holloway E, Scullion J, Shaw DE, Wardlaw A, Price D, Pavord I. Breathing exercises for asthma: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2008;64:55–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19052047?dopt=Abstract (accessed 29 Dec 2016).</ref><br> | |||

<br> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|lDplcbllr1c}} | {{#ev:youtube|lDplcbllr1c}} | ||

| Line 603: | Line 313: | ||

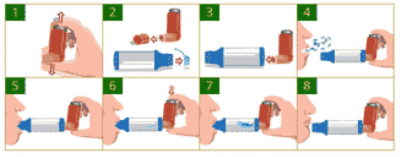

==== Correct Inhaler Use ==== | ==== Correct Inhaler Use ==== | ||

Proper inhaler use is vital to the good management of asthma in children. It is estimated that up to 25% of asthma sufferers use improper inhaler technique<ref name="Bernstein, 2014" | Proper inhaler use is vital to the good management of asthma in children. It is estimated that up to 25% of asthma sufferers use improper inhaler technique<ref name="Bernstein, 2014" />. Improper inhaler use has proven to correlate with poor asthma control and more frequent emergency hospital visits<ref name="Al-Jahdali et al. 2013">AL-Jahdali H, Ahmed A, AL-Harbi A, Khan M, Baharoon S, Bin Salih S, Halwani R, Al-Muhsen S. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2013;9:8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3605255/ (accessed 18 Jan 21017).</ref>. Poor technique is also associated with a lower quality of life and level of patient education is associated with poor inhaler technique<ref name="Hashmi et al. 2012">Hashmi A, Soomro JA, Memon A, Soomro TK. Incorrect Inhaler technique compromising quality of life of Asthmatic patients. Journal of Medicine 2012; 13:16-21 http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/JOM/article/view/7980 (accessed 10 Jan 2017).</ref>. As a result, children need to be educated on the proper use of the inhaler technique, and this is where physiotherapists may come in. | ||

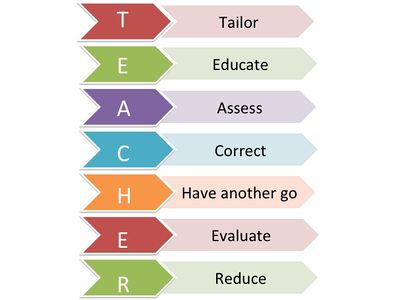

The T.E.A.C.H.E.R acronym is a great way to ensure children are aware of the correct care, and that their programme is tailored specifically to them. The figure below shows what the acronym stands for<ref name="Bernstein, 2014">Bernstein JA, Levy ML, editors. Clinical asthma: Theory and practice. Boca Raton: CRC/Taylor and Francis, 2014.</ref>: [[Image:Slide09.jpg|400x400px|right]] | |||

<br>'''Tailor''' – Tailor the method of delivery to suit your patient. Many younger children especially ones younger than 5 years old have difficulty timing breathing with the inhaler and a spacer is often used to remedy this problem. Children who have shallow patterns of breathing my also find using an inhaler difficult and benefit from using a spacer | |||

'''Educate''' - Educate the child in the correct timing of when to trigger the inhaler and how to take a deep breath. Explain to the child the importance of using the inhaler and why having correct technique is vital. | |||

'''Assess''' – Assess the patients technique, allow them to attempt using the inhaler independently without prompts. Focus on the timing of triggering the inhaler with their breathing. Pay close attention to any mistakes. | |||

'''Correct''' – After assessing the patient's technique, correct the patient on any mistakes they may have made. Reinforce the areas in which their technique was successful and correct areas in which they need to improve. | |||

'''Have Another go''' – Re-assess the patients technique and see if it has improved after correction. | |||

'''Evalute''' – Evaluate the childs technique and see it is of an adequate standard. If not correct and re-assess again. | |||

'''Reduce''' – Children are recommended to use their inhaler 15 minutes before physical activity and during an asthmatic attack. In general use, a patient should be recommended to use the inhaler as conservatively as possible. Health care professionals should recommend reduction in inhaler usage if possible. | |||

Reduce – Children are recommended to use their inhaler 15 minutes before physical activity and during | |||

==== Safe breathlessness ==== | ==== Safe breathlessness ==== | ||

As breathlessness is very subjective and can vary from person to person, choosing a point of safe breathlessness is very much down to the individual. There are no guidelines to determine what is classed as safe breathlessness, therefore parents, teachers, family members and clinicians must take a very subjective approach to this. Children should be encouraged to exercise, but stop if breathlessness gets worse than their perceived normal level. When completing a subjective assessment on a child with | As breathlessness is very subjective and can vary from person to person, choosing a point of safe breathlessness is very much down to the individual. There are no guidelines to determine what is classed as safe breathlessness, therefore parents, teachers, family members and clinicians must take a very subjective approach to this. Children should be encouraged to exercise, but stop if breathlessness gets worse than their perceived normal level. When completing a subjective assessment on a child with asthma, a visual breathlessness scale should be used to aid children as to where they fair on the scale, similar to a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain<ref name="Hawker et al. 2011">Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), Numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale. SF. Arthritis Care & Research 2011; 63:240–52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22588748 (accessed 21 Jan 2017).</ref>. The Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale<ref name="McGrath et al. 2005" /> is an example of this - as shown in section 3 regarding outcome measures - and allows the child to pick where they think they are on the scale to determine their level of breathlessness.<br> | ||

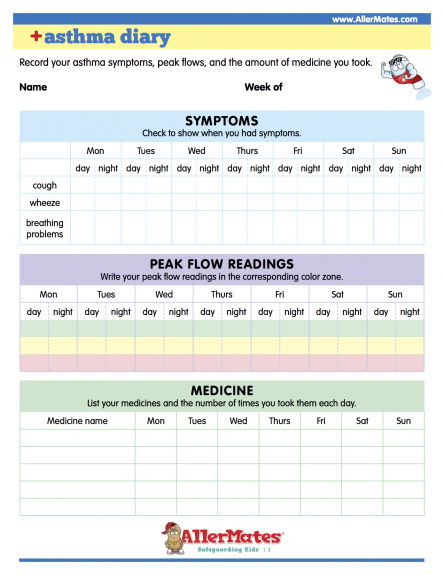

==== Asthma Diary ==== | ==== Asthma Diary ==== | ||

Effective management of your asthma is not solely based on administering the correct medication at the correct times and dosage. This is of course one of the most important aspects in order to keep your asthma well controlled, but by no means the only option. Asthma is an extremely variable condition and no two people’s asthma is likely to be identical. This emphasises the importance of education being an integral aspect of all interactions between the health care professionals and patients, and relevant to asthma patient’s of all ages. Although the focus of education for young children will predominantly be on the caregivers and parents, children as young as 3 years old can be educated on simple asthma management skills and personal triggers. Research | Effective management of your asthma is not solely based on administering the correct medication at the correct times and dosage. This is of course one of the most important aspects in order to keep your asthma well controlled, but by no means the only option. Asthma is an extremely variable condition and no two people’s asthma is likely to be identical. This emphasises the importance of education being an integral aspect of all interactions between the health care professionals and patients, and relevant to asthma patient’s of all ages. Although the focus of education for young children will predominantly be on the caregivers and parents, children as young as 3 years old can be educated on simple asthma management skills and personal triggers. Research has shown that although adolescents may have some degree of difficulty in adhering to asthma education, this could be enhanced through peer support group education with the added support of education given by the health care professional<ref name="Shah et al. 2001">Shah S. Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: Cluster randomised controlled. BMJ 2001;322:583. http://www.bmj.com/content/322/7286/583.short (accessed 5 Jan 2017).</ref> <ref name="Trollvik et al. 2013" /> . | ||

Management can be made easier by the application of an Asthma Diary, which can be made as simple or detailed as you require. However, the more detailed the information is the more beneficial it will be, not only for your child but also the asthma nurse or doctor, who can systematically tailor your treatment to your needs. Identification of what triggers your child’s asthma can sometimes be easily identifiable, however at times it can be complex, therefore keeping a daily asthma diary could help | Management can be made easier by the application of an Asthma Diary, which can be made as simple or detailed as you require. However, the more detailed the information is the more beneficial it will be, not only for your child but also the asthma nurse or doctor, who can systematically tailor your treatment to your needs. Identification of what triggers your child’s asthma can sometimes be easily identifiable, however at times it can be complex, therefore keeping a daily asthma diary could help<br> | ||

The asthma diary<ref name="Allermates, 2009">Allermates. Asthma diary. http://www.allermates.com/asthma/resources/asthma-diary/ (accessed 10 Jan 2017).</ref> includes a record of: | |||

[[Image:AsthmaDiary.png|right|475x575px]] | |||

*Symptoms: This would be beneficial to keep a record, so you can monitor whether your symptoms get better or worse over time. Recording the time when symptoms are worse and what triggered them would be of great benefit so measures can be undertaken to address these issues.<br>If you notice any of the following symptoms such as: | |||

The peak expiratory flow measurements are made using a peak flow meter (PEF), which can be important in the diagnosis and monitoring of asthma. Modern PEF meters are relatively inexpensive, portable, plastic and ideal for children to use in the home setting for day-to-day objective measurements of airflow limitation. | *Frequent waking throughout the night suffering from excessive coughing, wheezing and shortness of breath. | ||

*Administration of the reliever treatment at a much greater rate than normal, or if this doesn’t seem to be working in any way. | |||

*Upon wakening in the morning, you suffer from shortness of breath. | |||

*Finding it increasingly difficult to participate in your usual level of activity. | |||

*Then the most important thing is to phone your doctor who can administer the correct treatment, which can help you bring your child’s asthma back under control. | |||

*Peak Flow Readings: The peak expiratory flow measurements are made using a peak flow meter (PEF), which can be important in the diagnosis and monitoring of asthma. Modern PEF meters are relatively inexpensive, portable, plastic and ideal for children to use in the home setting for day-to-day objective measurements of airflow limitation. The PEF is a measure of the highest expiratory flow that can be generated following the child’s maximal inspiration. The reading will directly be influenced by airway diameter and can be a useful indication of the degree of bronchoconstriction in asthma sufferers<ref name="Main and Denehy, 2016">Main E, Denehy L. Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapy Adults and Paediatrics [Formerly Physiotherapy for respiratory and cardiac Problems]. United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone, 2016.</ref>. | |||

< | *Medication - This is extremely important to record both the various forms of medication the child takes and also the timeframe the medication was administered. This also includes any other types of medication they use, such as over the counter remedies. This information will allow the doctor or practice nurse to monitor how well controlled the child’s asthma is and how effective the medication is in controlling the asthma symptoms. Therefore, clinical decisions can be made whether to change, increase or decrease the medication to gain or maintain control<ref name="Ludman et al. 2016">Netdoctor. Asthma – the importance of keeping a daily asthma diary. http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/conditions/allergy-and-asthma/a6111/asthma-8211-the-importance-of-keeping-a-daily-asthma-diary/ (accessed 4 January 2017).</ref>. | ||

<br> | The asthma diary would also benefit from the recording of the child’s participation in daily activities and the effect these have on asthma symptoms. For example, the child may feel their asthma is well controlled but notice some degree of difficulty when participating in certain exercise or even running for the school bus. Recording of this information will allow your doctor or asthma nurse to generate a written self-management action plan, which is tailored to your child’s needs. For more information, please refer [http://www.allermates.com/asthma/resources/asthma-diary/ here]. According to the SIGN<ref name="SIGN, 2016" /> guidelines on the management of asthma, all patients of all ages should be offered self-management education, which should also include the development of a personalised asthma action plan. Research has shown that symptom-based written plans for children are effective in reducing emergency consultations<ref name="Bhogal et al. 2006" /><ref name="Zemek et al. 2008">Gibson PG, Powell H. Written action plans for asthma: An evidence-based review of the key components. Thorax 2004; 59: 94-99. http://thorax.bmj.com/content/59/2/94 (accessed 06 Jan 2017).</ref>.<br> | ||

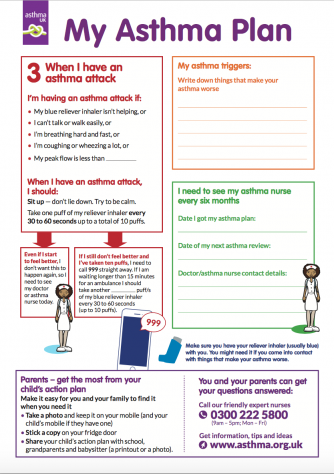

==== Asthma Action Plan ==== | |||

< | Since all children who are diagnosed with asthma are susceptible to asthma exacerbations at some point in time, knowing how to manage and prevent these episodes is extremely important<ref name="Gibson and Powell, 2004">Gibson PG, Powell H. Written action plans for asthma: An evidence-based review of the key components. Thorax 2004; 59: 94-99. http://thorax.bmj.com/content/59/2/94 (accessed 06 Jan 2017).</ref>. Active participation from the parent or individual with asthma in order to prevent exacerbations has led to the universal recommendation by both international and national guidelines to advocate the importance of asthma education for all affected patients, including the provision of a set of written instructions, often named Written Asthma Plans (WAP) or self-management action plans, to guide prevention and successful home management of symptoms and exacerbations<ref name="British Thoracic Society, 2016">British Thoracic Society. BTS/SIGN British guideline on the management of asthma. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/btssign-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma/ (accesed 4 January 2017).</ref><ref name="National Asthma Council, 2017">National Asthma Council Australia, Providing asthma management education for parents and children. Australian Asthma Handbook. http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/management/children/education (accessed 06 Jan 2017).</ref><ref name="Becker et al. 2005">Becker A, Lemière C, Bérubé D, Boulet LP, Ducharme FM, Fitzgerald M, Kovesi T. Summary of recommendations from the Canadian asthma consensus guidelines. CMAJ 2005; 173 (6 suppl): S1-S56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1329945/pdf/20050913.1s00001pS3.pdf (accessed 14 Jan 2017).</ref>. | ||

<br>A systematic review, which examined written asthma plans in children, concluded that there were significant reductions in acute care visits, children achieved better attendance records at school, had less nocturnal awakening and reported improved symptom scores when provision of a written action plan was implemented<ref name="Zemek et al. 2008" />. Research has shown that for children and adolescents, written asthma action plans that are based on symptoms seem to be more effective than those based on peak expiratory flow<ref name="Zemek et al. 2008" /><ref name="Bhogal et al. 2006">Bhogal SK, Zemek RL, Ducharme F. Written action plans for asthma in children. (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD005306</ref>. | |||

Using a written asthma action plan means: | Using a written asthma action plan means: | ||

You can share this with anyone who is looking after your child such as carer, family member or teacher at the child’s school. | |||

* You can use it if your child is suffering an asthma attack – it can be beneficial when the parent or caregiver is panicking or even during the middle of the night when it is difficult to be fully alert. | |||

In order to get the best from the asthma action plan it is important to discuss each section in detail with the child’s GP or asthma nurse and ask any questions needed. If the child is at an age where they can be involved it is important to include them in the discussion so effective self-management can be incorporated. Preparing children with asthma to take independent responsibility for their own asthma management and empowering them to show they are capable of doing so, is significant when understanding how their asthma is being looked after | * That the information about your child’s asthma is all written in one place which will give you peace of mind that the correct procedures will be followed if your child’s symptoms begin to deteriorate. | ||

* Your child is less likely to suffer an asthma attack or have asthma symptoms<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016" />. | |||

In order to get the best from the asthma action plan it is important to discuss each section in detail with the child’s GP or asthma nurse and ask any questions needed. If the child is at an age where they can be involved it is important to include them in the discussion so effective self-management can be incorporated. Preparing children with asthma to take independent responsibility for their own asthma management and empowering them to show they are capable of doing so, is significant when understanding how their asthma is being looked after<ref name="British Thoracic Society, 2016" />. | |||

<br> | <br>The asthma action plan should be taken to all regular asthma reviews so adaptions can be made if necessary<ref name="Asthma UK plan">Asthma UK. Your child's asthma action plan. https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/child/manage/action-plan/ (Accessed 10 January 2017).</ref>. Keep the asthma plan in an obvious place so access can be gained from a number of people and found easily, even a copy can be kept on the child’s phone if this is applicable<ref name="Asthma UK, 2016">Asthma UK. Asthma facts and statistics. https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/ (Accessed 26 January 2017).</ref>.<br> | ||

[[Image:Plan1.png|left|390x475px|x]] | [[Image:Plan1.png|left|390x475px|x]] | ||

| Line 697: | Line 388: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

For more information, please refer [https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/manage-your-asthma/action-plan/ here] | |||

==== Bronchodilators: The Correct Use ==== | |||

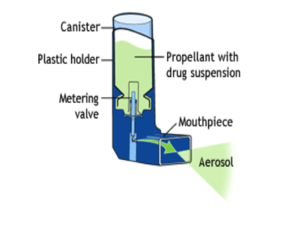

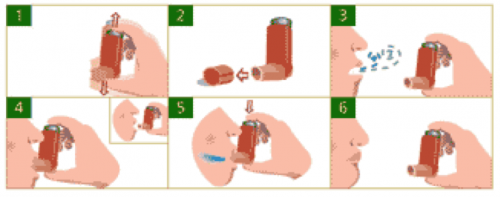

(Figure | [[Image:MDIPufferInhaler.png|right|300x300px]]A metered-dose inhaler, called an MDI for short, is a pressurized inhaler that delivers medication by using a propellant spray. A picture of the metered dose inhaler can be found on the right (Figure 20). | ||

'''Using a Puffer''' | |||

#Shake the inhaler well before use (3 or 4 shakes) | #Shake the inhaler well before use (3 or 4 shakes) | ||

#Remove the cap | #Remove the cap | ||

#Breathe out, away from your inhaler | #Breathe out, away from your inhaler | ||

#Bring the inhaler to your mouth. Place it in your mouth between your teeth and close you mouth around it | #Bring the inhaler to your mouth. Place it in your mouth between your teeth and close you mouth around it | ||

#Start to breathe in slowly. Press the top of you inhaler once and keep breathing in slowly until you have taken a full breath | #Start to breathe in slowly. Press the top of you inhaler once and keep breathing in slowly until you have taken a full breath | ||

#Remove the inhaler from your mouth, and hold your breath for about 10 seconds, then breathe out | #Remove the inhaler from your mouth, and hold your breath for about 10 seconds, then breathe out | ||

< | How to use a MDI<ref name="Asthma Society of Canada, 2017.b" /> [[Image:MDIUseExample.png|500x300px|right]] | ||

If you need a second puff, wait 30 seconds, shake your inhaler again, and repeat steps 3-6. After you've used your MDI, rinse out your mouth and record the number of doses taken. All puffers should be stored at room temperature.<br> | |||

Here are some important reminders about metered dose inhalers<ref name="Asthma Society of Canada, 2017.b">Asthma Society of Canada. How to use a metered-dose Inhaler. http://www.asthma.ca/adults/treatment/meteredDoseInhaler.php (accessed 12 Jan 2017).</ref>: | |||

*Always follow the instructions that come with your MDI.<br> | *Always follow the instructions that come with your MDI.<br> | ||

*Keep your reliever MDI somewhere where you can get it quickly if you need it, but out of children's reach. | *Keep your reliever MDI somewhere where you can get it quickly if you need it, but out of children's reach. | ||

| Line 770: | Line 423: | ||

*Many doctors recommend the use of a spacer, or a holding device to be used with the MDI. | *Many doctors recommend the use of a spacer, or a holding device to be used with the MDI. | ||

*Do not float the canister in water. | *Do not float the canister in water. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 781: | Line 430: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Using a Spacer''' | |||

<br> | [[Image:MDISpacerDiagram.gif|border|alt=|right]]<br> | ||

#Shake the inhaler well before use (3-4 shakes)<ref name="Asthma Society of Canada, 2017a.">Asthma Society of Canada. Spacers - How to use your Inhaler. http://www.asthma.ca/adults/treatment/spacers.php (accessed 12 Jan 2017).</ref> | |||

#Shake the inhaler well before use (3-4 shakes) | |||

#Remove the cap from your inhaler, and from your spacer, if it has one | #Remove the cap from your inhaler, and from your spacer, if it has one | ||

#Put the inhaler into the spacer | #Put the inhaler into the spacer | ||

#Breathe out, away from the spacer | #Breathe out, away from the spacer | ||

#Bring the spacer to your mouth, put the mouthpiece between your teeth and close your lips around it | #Bring the spacer to your mouth, put the mouthpiece between | ||

#your teeth and close your lips around it | |||

#Press the top of your inhaler once | #Press the top of your inhaler once | ||

#Breathe in very slowly until you have taken a full breath. If you hear a whistle sound, you are breathing in too fast. Slowly | #Breathe in very slowly until you have taken a full breath. If you hear a whistle sound, you are breathing in too fast. Slowly breathe in | ||

#Hold your breath for about ten seconds, then | #Hold your breath for about ten seconds, then breathe out | ||

Important Reminders About Spacers<ref name="Asthma Society of Canada, 2017a." />: | |||

*[[Image:MDISPacer.png|right|400x200px]]Always follow the instructions that come with your spacer. As well: | |||

*Always follow the instructions that come with your spacer. As well: | |||

*Only use your spacer with a pressurized inhaler, not with a dry-powder inhaler. | *Only use your spacer with a pressurized inhaler, not with a dry-powder inhaler. | ||

*Spray only one puff into a spacer at a time. | *Spray only one puff into a spacer at a time. | ||

*Use your spacer as soon as you've sprayed a puff into it. | *Use your spacer as soon as you've sprayed a puff into it. | ||

*Never let anyone else use your spacer. | *Never let anyone else use your spacer. | ||

*Keep your spacer away from heat sources. | *Keep your spacer away from heat sources. | ||