Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE): Difference between revisions

Katie White (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Maram Salem (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (290 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

< | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:David Greaves|David Greaves]], [[User:Lynette Fox|Lynette Fox]], and [[User:Katie White|Katie White]] as part of the [[Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} <br> | |||

</div> | |||

== Introduction == | |||

[[File:PNE.webp|right|frameless|234x234px]] | |||

Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts more than three months. It is a very common and prevalent problem that affects most age groups worldwide. Chronic pain is a multifactorial disorder that is influenced by biology, psychology, environmental, and social factors.<ref>Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Aug;123(2):e273-e283.</ref> Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is a strategy that aims to teach patients to reshape their mindset and perception of [[Pain Behaviours|pain]] despite these factors. It provides patients a better understanding of their condition and motivates them to become active participants in their treatment programs. | |||

Based on a large number of high-quality studies, it has been shown that teaching people with chronic pain more about the neuroscience of their pain produces immediate and long-term changes. PNE has been shown to have positive effects in reducing pain, disability, and psychosocial problems, improving patient's knowledge of pain mechanisms, facilitating movement and decreasing healthcare consumption.<ref>Zimney KJ, Louw A, Cox T, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. Pain neuroscience education: Which pain neuroscience education metaphor worked best?. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;75(1):1-7. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6739553/<nowiki/>(accessed 19.4.2022)</ref> | |||

== Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) == | |||

= | With respect to PNE, [[Chronic Pain and the Brain|chronic pain]] is not viewed as a result of unhealthy or dysfunctional tissues. Rather, it is due to [[Neuroplasticity|brain plasticity]] leading to hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, known as central sensitization.<ref name=":1">Nijs J, Girbés EL, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy. 2015; 20 (1): 216-220.</ref> The ultimate goal for Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is to increase pain tolerance with movement (e.g., be able to perform exercise with mild discomfort), reduce any fear associated with movement, and reduce central nervous system hypersensitivity. In practice, this often includes the use of educational pain analogies, re-education of patient misconceptions regarding disease pathogenesis, and guidance about lifestyle and movements modifications that can be introduced. | ||

PNE | There are two clinical indications for initiating Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)<ref name=":2">Nijs, J., Paul van Wilgen, C., Van Oosterwijck, J., van Ittersum, M., Meeus, M.,How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: Practice guidelines, Manual Therapy, 2011, 16:5, 413-418</ref>: | ||

* the clinical picture is dominated by central sensitization | |||

* illness coping mechanisms or poor illness perception is present | |||

[[Image:Effects_of_central_sensatisation.png|313x313px|alt=|thumb|Effects of central sensitization]] | |||

Central sensitization is when there is amplification of pain in the central nervous system. It can result in hypersensitivity to stimuli, responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli, and increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field. <ref>[[Central Sensitisation]]</ref>This can be assessed during the subjective and objective portion of a patient's evaluation. A physical therapist can determine what a patient's perception of their own pain is and how they cope with their pain. [[File:Upload_version_of_systemic_effects.jpg|alt=|thumb|426x426px|Pain behaviors caused by central sensitization]]PNE aims to reconceptualize pain to patients with these four main points: | |||

* Pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues | |||

* Pain is modulated by many factors from somatic, psychological, and social domains | |||

* The relationship between pain and the state of tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists | |||

* Pain can be conceptualized as the conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger<ref name=":0">Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical therapy reviews. 2007 Sep 1;12(3):169-78.</ref> | |||

==== | == Application of PNE == | ||

The application of PNE is most useful as part of a combination therapy for chronic pain that includes physiotherapy intervention (including [[Therapeutic Exercise|exercise therapy]]) and may or may not include [[Pain Medications|pharmacological treatment]]. Its application is best applied by trained and skilled clinicians with experience in managing patients with chronic pain conditions. Overall, PNE serves as a method of reconceptualizing a patient's perception of their pain experience, providing an avenue for reducing pain, disability and improving [[Quality of Life|quality of life]]<ref name=":0" />. PNE puts the complex process of describing the nerves and brain into a format that is easy to understand for everyone regardless of age, educational level, or ethnic group.<ref name=":10">Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.</ref>{{#ev:youtube|?v=6RGP_usIbBU|width}}<ref>Pain Neuroscience Education PAINWeek | |||

Available:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RGP_usIbBU (accessed 19.4.2022)</ref> | |||

Methods of PNE delivery vary but can typically involve around 4 hours of teaching that is provided to a group or individually, either in single or multiple sessions.<ref name=":4">Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy. 2011; 16(6):544-549.</ref>PNE consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurobiology and neurophysiology of pain and [[Pain Facilitation and Inhibition|pain processing]] by the [[Introduction to Neuroanatomy|nervous system]].<ref name=":10" /> It is implemented prior to administering physical therapy interventions with a verbal explanation. This is subsequently reinforced throughout the course of treatment to ensure proper carryover of reconceptualization of pain during and after discharge from physical therapy. | |||

During the first educational session, the clinician should explain central sensitization along with the use any of the following: pictures, booklets, pamphlets, metaphors, drawings, question/answer assignments, and neurophysiology pain questionnaires. Topics addressed include acute pain vs. chronic pain, how it evolves from acute pain to chronic pain, interpretation of stimuli to the nervous system, and external factors that may impact pain (such as anxiety, stress, depression, pain perceptions, and behavior). Patients are encouraged to read the handouts or brochures handed to them from the clinician at home.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

During subsequent sessions, the patient is encouraged to ask questions and receive clarification for any questions they may have about the neurophysiology of their pain. The clinician can address psychosocial aspects of a patient's pain during any visit. Some examples of clinically indicated advice that can be provided include advising the patient to stop worrying about their pain, reduce stress, implement relaxation techniques, and become more physically active. The treatment rationale should be provided throughout the patient's plan of care. Continually reinforcing and educating the patient regarding their pain physiology is recommended. The overarching goal is to motivate and encourage the patient to complete their treatment program in order to achieve their functional goals. <ref name=":2" /> | |||

Figure 4. illustrates the content of PNE education sessions with patients<ref name=":10" /> | |||

[[Image:Methods of PNE.jpg|center|Figure 4. displays the content of PNE education sessions|alt=Figure showing the content of PNE education sessions|369x369px]] | |||

An example of a metaphor or story that can be used with patients is provided here: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. | |||

=== PNE for Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions<ref name=":13">Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.</ref> === | |||

[[Image:Chronic MSK conditions.jpg|alt=|thumb|Chronic MSK conditions with positive PNE results |301x301px]]These conditions are often characterised by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitisation). Figure 5 highlights chronic musculoskeletal conditions that benefit from PNE, including osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, pelvic pain, whiplash, lateral epicondylitis, and low back pain.<ref name=":6">Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.</ref><ref name=":7">Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.</ref> | |||

Recent studies suggest that PNE in conjunction with either therapeutic exercise or manual therapy yielded significant reduction in pain ratings.<ref>Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E., Diener, I., The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2016, 32:5, 332-355.</ref> | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] | |||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine]] | |||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Pain]] | |||

[[ | |||

[[ | |||

Latest revision as of 16:11, 18 November 2023

Original Editor - David Greaves, Lynette Fox, and Katie White as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - David Greaves, Lynette Fox, Becky Mead, Katie White, Kim Jackson, Maram Salem, Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Vanessa Rhule, Rachael Lowe, Lauren Lopez, Rishika Babburu and Evan Thomas

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts more than three months. It is a very common and prevalent problem that affects most age groups worldwide. Chronic pain is a multifactorial disorder that is influenced by biology, psychology, environmental, and social factors.[1] Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is a strategy that aims to teach patients to reshape their mindset and perception of pain despite these factors. It provides patients a better understanding of their condition and motivates them to become active participants in their treatment programs.

Based on a large number of high-quality studies, it has been shown that teaching people with chronic pain more about the neuroscience of their pain produces immediate and long-term changes. PNE has been shown to have positive effects in reducing pain, disability, and psychosocial problems, improving patient's knowledge of pain mechanisms, facilitating movement and decreasing healthcare consumption.[2]

Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)[edit | edit source]

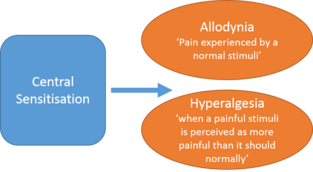

With respect to PNE, chronic pain is not viewed as a result of unhealthy or dysfunctional tissues. Rather, it is due to brain plasticity leading to hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, known as central sensitization.[3] The ultimate goal for Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is to increase pain tolerance with movement (e.g., be able to perform exercise with mild discomfort), reduce any fear associated with movement, and reduce central nervous system hypersensitivity. In practice, this often includes the use of educational pain analogies, re-education of patient misconceptions regarding disease pathogenesis, and guidance about lifestyle and movements modifications that can be introduced.

There are two clinical indications for initiating Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)[4]:

- the clinical picture is dominated by central sensitization

- illness coping mechanisms or poor illness perception is present

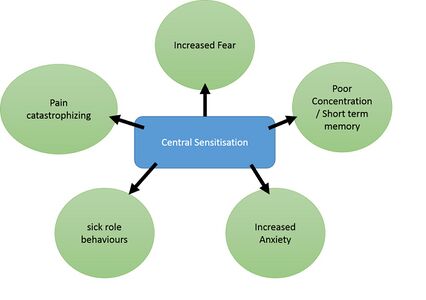

Central sensitization is when there is amplification of pain in the central nervous system. It can result in hypersensitivity to stimuli, responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli, and increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field. [5]This can be assessed during the subjective and objective portion of a patient's evaluation. A physical therapist can determine what a patient's perception of their own pain is and how they cope with their pain.

PNE aims to reconceptualize pain to patients with these four main points:

- Pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues

- Pain is modulated by many factors from somatic, psychological, and social domains

- The relationship between pain and the state of tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists

- Pain can be conceptualized as the conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger[6]

Application of PNE[edit | edit source]

The application of PNE is most useful as part of a combination therapy for chronic pain that includes physiotherapy intervention (including exercise therapy) and may or may not include pharmacological treatment. Its application is best applied by trained and skilled clinicians with experience in managing patients with chronic pain conditions. Overall, PNE serves as a method of reconceptualizing a patient's perception of their pain experience, providing an avenue for reducing pain, disability and improving quality of life[6]. PNE puts the complex process of describing the nerves and brain into a format that is easy to understand for everyone regardless of age, educational level, or ethnic group.[7]

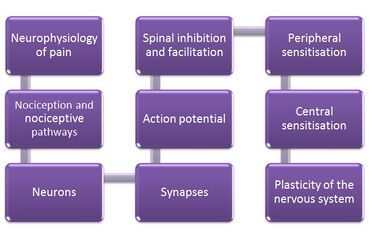

Methods of PNE delivery vary but can typically involve around 4 hours of teaching that is provided to a group or individually, either in single or multiple sessions.[9]PNE consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurobiology and neurophysiology of pain and pain processing by the nervous system.[7] It is implemented prior to administering physical therapy interventions with a verbal explanation. This is subsequently reinforced throughout the course of treatment to ensure proper carryover of reconceptualization of pain during and after discharge from physical therapy.

During the first educational session, the clinician should explain central sensitization along with the use any of the following: pictures, booklets, pamphlets, metaphors, drawings, question/answer assignments, and neurophysiology pain questionnaires. Topics addressed include acute pain vs. chronic pain, how it evolves from acute pain to chronic pain, interpretation of stimuli to the nervous system, and external factors that may impact pain (such as anxiety, stress, depression, pain perceptions, and behavior). Patients are encouraged to read the handouts or brochures handed to them from the clinician at home.[4]

During subsequent sessions, the patient is encouraged to ask questions and receive clarification for any questions they may have about the neurophysiology of their pain. The clinician can address psychosocial aspects of a patient's pain during any visit. Some examples of clinically indicated advice that can be provided include advising the patient to stop worrying about their pain, reduce stress, implement relaxation techniques, and become more physically active. The treatment rationale should be provided throughout the patient's plan of care. Continually reinforcing and educating the patient regarding their pain physiology is recommended. The overarching goal is to motivate and encourage the patient to complete their treatment program in order to achieve their functional goals. [4]

Figure 4. illustrates the content of PNE education sessions with patients[7]

An example of a metaphor or story that can be used with patients is provided here: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education.

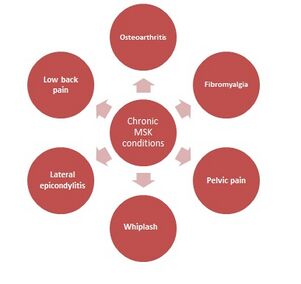

PNE for Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions[10][edit | edit source]

These conditions are often characterised by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitisation). Figure 5 highlights chronic musculoskeletal conditions that benefit from PNE, including osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, pelvic pain, whiplash, lateral epicondylitis, and low back pain.[11][12]

Recent studies suggest that PNE in conjunction with either therapeutic exercise or manual therapy yielded significant reduction in pain ratings.[13]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Aug;123(2):e273-e283.

- ↑ Zimney KJ, Louw A, Cox T, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. Pain neuroscience education: Which pain neuroscience education metaphor worked best?. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;75(1):1-7. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6739553/(accessed 19.4.2022)

- ↑ Nijs J, Girbés EL, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy. 2015; 20 (1): 216-220.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Nijs, J., Paul van Wilgen, C., Van Oosterwijck, J., van Ittersum, M., Meeus, M.,How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: Practice guidelines, Manual Therapy, 2011, 16:5, 413-418

- ↑ Central Sensitisation

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical therapy reviews. 2007 Sep 1;12(3):169-78.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.

- ↑ Pain Neuroscience Education PAINWeek Available:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RGP_usIbBU (accessed 19.4.2022)

- ↑ Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy. 2011; 16(6):544-549.

- ↑ Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.

- ↑ Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.

- ↑ Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.

- ↑ Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E., Diener, I., The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2016, 32:5, 332-355.