Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 238: | Line 238: | ||

*Stretch: levator scapulae, the scalenes, pectoralis minor and major | *Stretch: levator scapulae, the scalenes, pectoralis minor and major | ||

*Strengthen: rhomboids, serratus anterior, lower & middle traps, other observed postural weaknesses | *Strengthen: rhomboids, serratus anterior, lower & middle traps, other observed postural weaknesses | ||

*Mobilizations (godges)<ref name=" | *Mobilizations (godges)<ref name="Vanti" /><ref name="hooper" />: | ||

**1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space | **1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space | ||

***Note: 1st rib mobility may irritate some patients | ***Note: 1st rib mobility may irritate some patients | ||

| Line 244: | Line 244: | ||

**Acromioclavicular jt | **Acromioclavicular jt | ||

**Cervical ROM | **Cervical ROM | ||

*Taping: some patients with severe symptoms respond to additional taping, adhesive bandages or braces to elevate and retract the shoulder girdle.<ref name=" | *Taping: some patients with severe symptoms respond to additional taping, adhesive bandages or braces to elevate and retract the shoulder girdle.<ref name="Vanti" /> | ||

*HEP: | *HEP: | ||

**Emphasize posture | **Emphasize posture | ||

Revision as of 02:04, 28 November 2011

Original Editors

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases: CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library,

Keywords: thoracic outlet syndrome, conservative management, anatomy, physical therapy

Timeline: 10/12/11 - 11/27/11

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The term ‘thoracic outlet syndrome’ (TOS) was originally coined in 1956 by RM Peet to indicate compression of the neurovascular structures in the interscalene triangle possibly corresponding to the etiology of symptoms. Since Peet provided this definition, the condition has emerged as one of the most controversial topics in musculoskeletal medicine and rehabilitation [1]. This controversy extends to almost every aspect of the pathology including the definition, incidence, pathoanatomical contributions, diagnosis and treatment. Controversy with this diagnosis begins with the definition because the term TOS only outlines the location of the problem without actually defining what comprises the problem [1]. TOS encompasses a wide range of clinical manifestations due to compression of nerves and vessels during their passage through the cervicothoracobrachial region.

Investigators have named two main categories of TOS: vascular forms (arterial or venous) which raise few diagnostic problems, and ‘‘neurological’’ forms, which are by far the most frequent as they represent more than 95% of all cases of TOS. The ‘‘neurological forms’’ are classified in the ‘‘true’’ neurological form associated with neurological deficits (mostly muscular atrophy), and disputed neurological forms (with no objective neurological deficit) [2]. The disputed neurological forms are another to blame for controversy of this topic due to the absence of objective criteria to confirm the diagnosis.

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

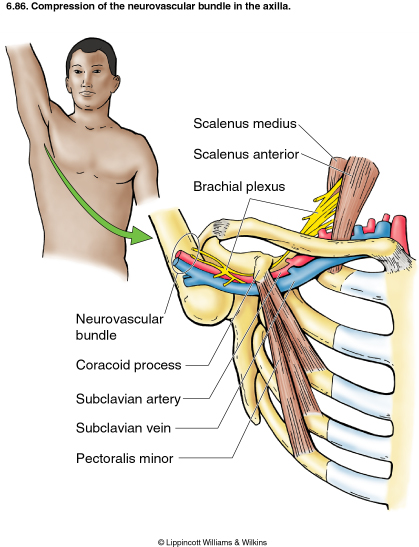

The neural container described as the thoracic outlet is comprised of several structures. Proximally, the cervicoaxillary canal is divided by the first rib into two parts. The proximal portion is comprised of the interscalene triangle and the costoclavicular space, wheras the axilla comprises the distal aspect of the canal. The proximal portion is more clinically relevant due to the potential of neurovascular compression occurring there.

More specifically, the thoracic outlet includes three limited spaces extending from the cervical spine and mediastinum to the lower border of the pec minor muscle. The three compartments include the interscalene triangle, the costoclavicular space, and the throaco-coraco-pectoral space. The interscalene triangle is bordered by the anterior scalene, middle scalene, and the medial surface of the first rib. The trunks of the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery travel through this triangle. The costoclavicular space is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula. The borders of the thoraco-coraco-pectoral space include the coracoid process superiorly, the pec minor anteriorly, and ribs 2-4 posteriorly.

Certain anatomical abnormalities can be potentially compromising to the thoracic outlet as well. These include the presence of a cervical rib, congenital soft tissue abnormalities, clavicular hypomobility [1], and functionally acquired anatomical changes [2]. Cervical ribs form off of the 7th cervical vertebrae and are found in approximately 1% of the population, with only 10% of these people ever experiencing adverse symptoms. Soft tissue abnormalities may create compression or tension loading of the neurovascular structures found within the thoracic outlet. Researchers have found different congenital morphologies of the scalene muscles found in individuals with TOS such as hypertrophy or a broader middle scalene attachment on the 1st rib. Another complicating soft tissue anomaly found is fibrous bands that increase the stiffness and decrease compliance of the thoracic container, resulting in an increase potential for neurovascular load. These soft tissue abnormalities are usually picked up with magnetic resonance imaging [1]. Lastly, Laulan and her colleagues introduce a mechanism of functional acquired anatomical changes that occur with compensation and repetitive activities (usually overhead). In this population, upper limb dysfunction or a muscle imbalance of the neck and shoulder region is considered to be responsible [2].

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

TOS affects approximately 8% of the population, with a female to male ratio of up to 4:1. It is rarely seen in children, with a mean age of affected patients in the fourth decade. Almost all cases of TOS (95-98%) affect the brachial plexus, with the other 2-5% affecting vascular structures, such as the subclavian artery and vein. There are three separate spaces in the thoracic outlet where anatomical variation can potentially lead to TOS.

Cervical ribs are present in approximately 0.5-0.6% of the population, 50-80% of which are bilateral, and 10-20% produce symptoms; the female to male ratio is 2:1. Cervical ribs and the fibromuscular bands connected to them are the cause of most neural compression. [3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome are variable from patient to patient due to the location of nerve and/or vascular involvement. Symptoms range from mild pain and sensory changes to limb threatening complications in severe cases. Patients with thoracic outlet syndrome will most likely present with paresthesia in upper extremity, neck pain, trapezius pain, supraclavicular pain, chest pain, and occipital pain. Patients with upper plexus (C5,6,7) involvement can present with pain in anterior neck from the clavicle up to and including the mandible, ear, and mastoid region. These symptoms can continue into the anterior chest, scapular region, trapezius and into lateral part of the arm continuing all the way to the thumb and index finger. Patients with lower plexus (C8,T1) involvement typically present with symptoms along the medial side of the arm and hand with potential involvement in the anterior shoulder and axillary region. There are four categories of thoracic outlet syndrome and each presents with unique signs and symptoms (see Table 1). Typically thoracic outlet syndrome does not follow a dermatomal or myotomal pattern unless there is nerve root involvement which will be important in determining your PT diagnosis and planning your treatment.

| Arterial TOS | Venous TOS | True TOS | Disputed Neurogenic TOS |

|

|

|

|

Compressors* - a patient that experiences symptoms throughout the daytime while using prolonged postures resulting in increased tension or compression of the thoracic outlet

Releasers* - a patient that experiences a release phenomenon (release of tension or compression to thoracic outlet) that often awakes them at night

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due the variability of presentation TOS can be difficult to tease out from other pathologies with common presentations. A thorough history and evaluation must be done to determine if the patient’s symptoms are truly TOS. The following pathologies are common differential diagnosis for TOS:

• Carpal tunnel syndrome

• DeQuervain’s tenosynovitis

• Lateral/medial epicondylitis

• Complex regional pain syndrome

• Horner’s Syndrome

• Raynaud’s disease

• Nerve root involvement

Systematic causes of brachial plexus pain include:

• Pancoast’s Syndrome

• Radiation induced brachial plexopathy

• Parsonage Turner Syndrome

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

DASH (Disability of Arm Shoulder and Hand)

SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index)

NPRS (Numeric Pain Rating Scale)

Examination

[edit | edit source]

The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list and examination should be individualized to the patient.

History[4]

- Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs/symptoms have affected his/her function.

- Type of symptoms

- Location and amplitude of symptoms

- Irritability of symptoms

- Onset and development over time

- Aggravating/alleviating factors

- Disability

Physical Examination[4]

- Observation

- Posture

- Cyanosis

- Edema

- Paleness

- Atrophy

- Palpation

- Temperature changes

- Supraclavicular fossa

- Neurological Screen

- MMT & Flexibility

- Scalene

- Pectoralis major/minor

- Levator scapulae

- Sternocleidomastoid

- Serratus anterior

- Elevated Arm Stress

- Adson's

- Wright's

- Cyriax Release

- Supraclavicular Pressure

- Costoclavicular Maneuver

- Upper Limb Tension

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR- |

| Elevated Arm Stress | 52-84% | 30-100% | 1.2-5.2 | 0.4-0.53 |

| Adson's | 79% | 74-100% | 3.29 | 0.28 |

| Wright's | 70-90% | 29-53% | 1.27-1.49 | 0.34-0.57 |

| Cyriax Release | NT | 77-97% | NA | NA |

| Supraclavicular Pressure | NT | 85-98% | NA | NA |

| Costoclavicular Maneuver | NT | 53-100% | NA | NA |

| Upper Limb Tension | 90% | 38% | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion | 100% | NT | NA | NA |

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been prescribed to reduce pain and inflammation. Botulinum injections to the anterior and middle scalenes have also found to temporarily reduce pain and spasm from neurovascular compression. Surgical management of TOS should only be considered after conservative treatment has been proven ineffective. However, limb-threatening complications of vascular TOS have been indicated for surgical intervention[5].

Neurogenic TOS: Surgical decompression should be considered for those with true neurological signs or symptoms. These include weakness, wasting of the hand intrinsic muscles, and conduction velocity less than 60 m/sec. The first rib can be a major contributor to TOS. There is controversy, however, regarding the necessity of a complete resection to reduce the chance of reattachment of the scalenes, scar tissue development, or bony growth of the remaining tissue. In addition to the first rib, cervical ribs are removed, scalenectomies can be performed, and fibrous bands can be excised[5]. Terzis found that the supraclavicular approach to treatment to be an effective and precise surgical method [6].

Arterial TOS: Decompression can include cervical and/or first rib removal and scalene muscle revision. The subclavian can then be inspected for degeneration, dilation, or aneurysm. Saphenous vein graft or synthetic prosthesis can then be used if necessary[5].

Venous TOS: Thrombolytic therapy is the first line of treatment for these patients. Because of the risk of recurrence, many recommend removal of the first rib is necessary even when thrombolytic therapy completely opened the vein. Angioplasty can then be used to treat those with venous stenosis[5].

Some larger-chested women have sagging shoulders that increase pressure on the neurovascular structures in the thoracic outlet. A supportive bra with wide and posterior-crossing straps can help reduce tension. Extreme cases may resort to breast-reduction surgery to relieve TOS and other biomechanical problems.[4][3]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Conservative management should be the first strategy to treat TOS since most cases are caused by muscle imbalances and posture. Conservative management includes physical therapy, which focuses on pain management, nerve gliding techniques, muscle endurance, stretching, and patient education. Since every patient presents differently, treatment needs to be individualized.[5] (godges)

Physical Therapy (pre-operative)

The primary purpose is to treat the patient’s TOS with out resorting to surgery.

Stage 1:

The goal of this initial stage is for the patient to decrease and obtain control of his/her symptoms resulting from TOS.

Early treatment will focus on symptom reduction before addressing biomechanical corrections. Cervical traction in combination with a hot pack and light exercise may reduce pain and irritable symptoms for some acute patients.[5]

Patient Education:

Avoidance: identify activities, postures, and actions that exacerbate symptoms in order to avoid them. (godges)

Sleep positions: avoid arm abduction and overhead positions. Patients that wake up at night from pain are considered “releasers”. Some patients who can’t control positioning may need arm or leg sleeves to pin down. These patients should sleep on their uninvolved side or in supine with supportive pillows under the arms[5]

Prognosis: TOS process (with and with out treatment) and potential prognosis to encourage compliance with HEP and activity modifications[5]

Address the patient’s breathing techniques as the scalenes and other accessory muscles often compensate to elevate the ribcage during inspiration. Encouraging diaphragmatic breathing will lessen the work load on already overused or tight scalenes and can possibly reduce symptoms. Since exercise and vigorous aerobic activity promote heavy breathing, the patient should take caution to not exacerbate his/her symptoms.[5]

Stage 2:

Once the patient has control of his/her symptoms, the patient can move to this stage of treatment. The goal of this stage is to directly address the tissues that create structural limitations of motion and compression. Expect to exacerbate the patient’s symptoms a little, but it should not last past the treatment session.

Methods such as soft tissue manipulation and manual techniques can improve flexibility around the thoracic outlet. Joint mobilizations include the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, scapulothoracic, first rib, and cervical spine joints. A combination of these methods during treatment will increase the thoracic outlet space and relieve compression on the neurovascular structures. Nerve mobilization techniques such as sliding and tensioning will address the patient’s neural tension involvement. (godges)

- Stretch: levator scapulae, the scalenes, pectoralis minor and major

- Strengthen: rhomboids, serratus anterior, lower & middle traps, other observed postural weaknesses

- Mobilizations (godges)[4][5]:

- 1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space

- Note: 1st rib mobility may irritate some patients

- Sternoclavicular jt

- Acromioclavicular jt

- Cervical ROM

- 1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space

- Taping: some patients with severe symptoms respond to additional taping, adhesive bandages or braces to elevate and retract the shoulder girdle.[4]

- HEP:

- Emphasize posture

- 1st rib self mobilizations with a towel

- Doorway stretches

Stage 3:

Treatment should increase in intensity, using the same techniques from stage 2, while adding conditioning and strengthening components to the postural muscles. (godges)

Post-Op Physical Therapy (godges)

If a patient does require surgery, then physical therapy should follow immediately to prevent scar tissue and return the patient to full function.

Precautions:

- Don’t lift more than 5lbs during first 6wks post op

- Do not push through new or increased pn

- Report any swelling of surgical or scapular area to surgeon immediately

- Report increased heat, redness, increased pn, drainage, HA, dizziness, n/t hands feet groin or LBP that is new.

- Symptoms lasting longer than 2hrs would indicate need to modify the exercise program

Scalenectomy and neurolysis procedures without 1st rib involvement:

- Early Care: wound care, edema control, scar management, ROM, nerve gliding, drain management, arm sling 2 weeks when active, no sling sitting or sleeping, instead elevated on pillow.

- HEP: edema control, sling use, drainage, sleeping on uninvolved side with supporting pillow for involved side

- Week 1: ROM, nerve glides, cervical ROM, shldr pendulums, hand tendon gliding exercises, Gentle ROM, active and active assisted ROM. 3-4x daily, drain removal at approx 3-5days

- Week 2: sutures to be removed and continue gliding exercises for neck and UE

- Week 3: scar massage and desensitization, minimal weight introduction

- Week 4: phonophoresis to scar site, brachial plexus massage, strengthening exercises. This part of the tx becomes very individualized (how active was pt pre-op). if returning to work, eval ergonomic/body mechanics

- Week 5: progress strengthening exercises

- Week 6: ergonomic training, work-simulated/functional activities. Pt may now lift 5lbs

- Week 7-12: increasing intensity and endurance to function

Physical therapy typically lasts 3 months, with sessions 2-3x week.

Daily stretching for 2yrs to prevent scar contraction, (godges)

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Currently, the research indicates that a conservative treatment approach often provides positive outcomes for TOS compared to non-conservative approaches. Physical therapy can address most problems associated with TOS such as muscle imbalances and postural changes, while saving patients' time and money.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Journal Of Manual &amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy (Maney Publishing) [serial online]. June 2010;18(2):74-83. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 20, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Laulan J, Fouquet B, Rodaix C, Jauffret P, Roquelaure Y, Descatha A. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Definition, Aetiological Factors, Diagnosis, Management and Occupational Impact. Journal Of Occupational Rehabilitation [serial online]. September 2011;21(3):366-373. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Boezaart, AP, et al. Neurogenic thoracic outlet sndrome: A case report and review of the literature. International Journal of Shoulder Surgery. 2010;4:27-35.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. Europa Medicophysica. 2007;43:55-70. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(3):132-138.

- ↑ Terzis J, Kokkalis Z, Supraclavicular approach for thoracic outlet syndrome. American Association for Hand Surgery. Dec 2010:326-337