Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

[http://thoracicoutletsyndromes.com/index.html thoracicoutletsyndromes.com] | [http://thoracicoutletsyndromes.com/index.html thoracicoutletsyndromes.com] | ||

[http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/thoracic/thoracic.htm NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page] | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Revision as of 21:56, 27 November 2011

Original Editors

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

add text here related to databases searched, keywords, and search timeline

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The term ‘thoracic outlet syndrome’ (TOS) was originally coined in 1956 by RM Peet to indicate compression of the neurovascular structures in the interscalene triangle corresponding to the possible etiology of the symptoms. Since Peet provided this definition, the condition has emerged as one of the most controversial topics in musculoskeletal medicine and rehabilitation [1]. This controversy extends to almost every aspect of the pathology including the definition, incidence, pathoanatomical contributions, diagnosis and treatment. Controversy with this diagnosis begins with the definition because the term TOS only outlines the location of the problem without actually defining what comprises the problem [1]. TOS encompasses a wide range of clinical manifestations due to compression of nerves and vessels during their passage through the cervicothoracobrachial region.

Investigators have named two main categories of TOS: vascular forms (arterial or venous) which raise few diagnostic problems, and ‘‘neurological’’ forms, which are by far the most frequent as they represent more than 95% of all cases of TOS. The ‘‘neurological forms’’ are classified in the ‘‘true’’ neurological form associated with neurological deficits (mostly muscular atrophy), and disputed neurological forms (with no objective neurological deficit) [2]. The disputed neurological forms are another to blame for controversy of this topic due to the absence of objective criteria to confirm the diagnosis.

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

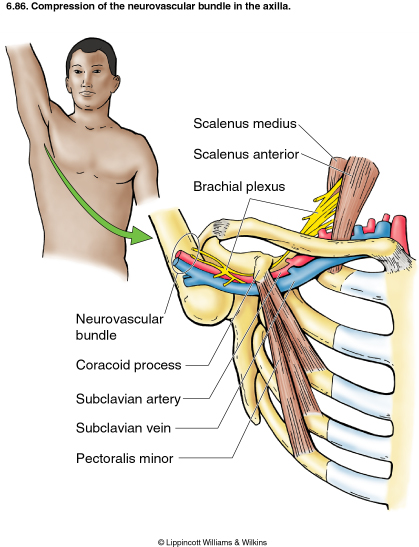

The neural container described as the thoracic outlet is comprised of several structures. Proximally, the cervicoaxillary canal is divided by the first rib into two parts. The proximal portion is comprised of the interscalene triangle and the costoclavicular space, wheras the axilla comprises the distal aspect of the canal. The proximal portion is more clinically relevant due to the potential of neurovascular compression occurring there.

More specifically, the thoracic outlet includes three limited spaces extending from the cervical spine and mediastinum to the lower border of the pec minor muscle. The three compartments include the interscalene triangle, the costoclavicular space, and the throaco-coraco-pectoral space. The interscalene triangle is bordered by the anterior scalene, middle scalene, and the medial surface of the first rib. The trunks of the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery travel through this triangle. The costoclavicular space is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula. The borders of the thoraco-coraco-pectoral space include the coracoid process superiorly, the pec minor anteriorly, and ribs 2-4 posteriorly.

Certain anatomical abnormalities can be potentially compromising to the thoracic outlet as well. These include the presence of a cervical rib, congenital soft tissue abnormalities, clavicular hypomobility [1], and functionally acquired anatomical changes [2]. Cervical ribs form off of the 7th cervical vertebrae and are found in approximately 1% of the population, with only 10% of these people ever experiencing adverse symptoms. Soft tissue abnormalities may create compression or tension loading of the neurovascular structures found within the thoracic outlet. Researchers have found different congenital morphologies of the scalene muscles found in individuals with TOS such as hypertrophy or a broader middle scalene attachment on the 1st rib. Another complicating soft tissue anomaly found is fibrous bands that increase the stiffness and decrease compliance of the thoracic container, resulting in an increase potential for neurovascular load. These soft tissue abnormalities are usually picked up with magnetic resonance imaging [1]. Lastly, Laulan and her colleagues introduce a mechanism of functional acquired anatomical changes that occur with compensation and repetitive activities (usually overhead). In this population, upper limb dysfunction or a muscle imbalance of the neck and shoulder region is considered to be responsible [2].

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

add text here

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome are variable from patient to patient due to the location of nerve and/or vascular involvement. Symptoms range from mild pain and sensory changes to limb threatening complications in severe cases. Patients with thoracic outlet syndrome will most likely present with paresthesia in upper extremity, neck pain, trapezius pain, supraclavicular pain, chest pain, and occipital pain. Patients with upper plexus (C5,6,7) involvement can present with pain in anterior neck from the clavicle up to and including the mandible, ear, and mastoid region. These symptoms can continue into the anterior chest, scapular region, trapezius and into lateral part of the arm continuing all the way to the thumb and index finger. Patients with lower plexus (C8,T1) involvement typically present with symptoms along the medial side of the arm and hand with potential involvement in the anterior shoulder and axillary region. There are four categories of thoracic outlet syndrome and each presents with unique signs and symptoms (see Table 1). Typically thoracic outlet syndrome does not follow a dermatomal or myotomal pattern unless there is nerve root involvement which will be important in determining your PT diagnosis and planning your treatment.

| Arterial TOS | Venous TOS | True TOS | Disputed Neurogenic TOS |

|

|

|

|

Compressors* - a patient that experiences symptoms throughout the daytime while using prolonged postures resulting in increased tension or compression of the thoracic outlet

Releasers* - a patient that experiences a release phenomenon (release of tension or compression to thoracic outlet) that often awakes them at night

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due the variability of presentation TOS can be difficult to tease out from other pathologies with common presentations. A thorough history and evaluation must be done to determine if the patient’s symptoms are truly TOS. The following pathologies are common differential diagnosis for TOS:

• Carpal tunnel syndrome

• DeQuervain’s tenosynovitis

• Lateral/medial epicondylitis

• Complex regional pain syndrome

• Horner’s Syndrome

• Raynaud’s disease

• Nerve root involvement

Systematic causes of brachial plexus pain include:

• Pancoast’s Syndrome

• Radiation induced brachial plexopathy

• Parsonage Turner Syndrome

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

DASH (Disability of Arm Shoulder and Hand)

SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index)

Examination

[edit | edit source]

The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list and examination should be individualized to the patient.

History

- Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs/symptoms have affected his/her function.

- Type of symptoms

- Location and amplitude of symptoms

- Irritability of symptoms

- Onset and development over time

- Aggravating/alleviating factors

- Disability

Physical Examination

- Observation

- Posture

- Cyanosis

- Edema

- Paleness

- Atrophy

- Palpation

- Temperature changes

- Supraclavicular fossa

- Neurological Screen

- MMT & Flexibility

- Scalene

- Pectoralis major/minor

- Levator scapuae

- Sternocleidomastoid

- Serratus anterior

- Elevated Arm Stress

- Adson's

- Wright's

- Cyriax Release

- Supraclavicular Pressure

- Costoclavicular Maneuver

- Upper Limb Tension

- Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR- |

| Elevated Arm Stress | 52-84% | 30-100% | 1.2-5.2 | 0.4-0.53 |

| Adson's | 79% | 74-100% | 3.29 | 0.28 |

| Wright's | 70-90% | 29-53% | 1.27-1.49 | 0.34-0.57 |

| Cyriax Release | NT | 77-97% | NA | NA |

| Supraclavicular Pressure | NT | 85-98% | NA | NA |

| Costoclavicular Maneuver | NT | 53-100% | NA | NA |

| Upper Limb Tension | 90% | 38% | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion | 100% | NT | NA | NA |

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been prescribed to reduce pain and inflammation. Botulinum injections to the anterior and middle scalenes have also found to temporarily reduce pain and spasm from neurovascular compression. Surgical management of TOS should only be considered after conservative treatment has been proven ineffective. However, limb-threatening complications of vascular TOS have been indicated for surgical intervention[3].

Neurogenic TOS: Surgical decompression should be considered for those with true neurological signs or symptoms. These include weakness, wasting of the hand intrinsic muscles, and conduction velocity less than 60 m/sec. The first rib can be a major contributor to TOS. There is controversy, however, regarding the necessity of a complete resection to reduce the chance of reattachment of the scalenes, scar tissue development, or bony growth of the remaining tissue. In addition to the first rib, cervical ribs are removed, scalenectomies can be performed, and fibrous bands can be excised[3].

Arterial TOS: Decompression can include cervical and/or first rib removal and scalene muscle revision. The subclavian can then be inspected for degeneration, dilation, or aneurysm. Saphenous vein graft or synthetic prosthesis can then be used if necessary[3].

Venous TOS: Thrombolytic therapy is the first line of treatment for these patients. Because of the risk of recurrence, many recommend removal of the first rib is necessary even when thrombolytic therapy completely opened the vein. Angioplasty can then be used to treat those with venous stenosis[3].

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

add text here

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

thoracicoutletsyndromes.com NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Journal Of Manual & Manipulative Therapy (Maney Publishing) [serial online]. June 2010;18(2):74-83. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 20, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Laulan J, Fouquet B, Rodaix C, Jauffret P, Roquelaure Y, Descatha A. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Definition, Aetiological Factors, Diagnosis, Management and Occupational Impact. Journal Of Occupational Rehabilitation [serial online]. September 2011;21(3):366-373. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(3):132-138.