The Effectiveness of Core Stability Exercise in the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain

Original Editor - .... as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Josh Plail, Yann Moysey, Timothy Sheehy, Samuel Soroya, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe and Admin

Chronic Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

This wiki page aims to investigate the effectivness of core stability exercises for chronic non- specific low back pain. We will discuss the evidence for and against the intervention with regards to general exercise, measuring "effectivness" using pain (primary) and function (secondary) as our outcome measures. In conjunction we have provided a overview of chronic low back pain and core stability exercises (To see more extensive details please see links to other relvant physiopedia pages). From reading this we hope students and clinicians a like can make their own mind up about the use of core stability exercises in clinical practice.

Background[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is an extremely common patient complaint with approximately 80% of the World population developing low back pain at some point (Deyo and Weinstein, 2001). 1/3 of the UK population will experience back pain each year (NICE 2009). It is the main cause of years lived with disability (Vos 2012). It is among 10 of the leading reasons for patient visits to medical facilities. (Patel and Ogle 2000). Non-specific low back pain is tension/soreness and or stiffness in the lower back region whereby it is not possible to find a cause for the pain (NICE 2009). Most cases resolve fairly quickly, but a significant number of patients develop chronic lower back pain. Patients experience unremitting pain and often become functionally impaired. Chronic LBP represents a greater financial burden in the form of direct costs resulting from loss of work and medical expenses, as well as indirect costs (Dagenais et al. 2008).

Definition[edit | edit source]

Generally there is a scarcity of information on the prevalence and incidence of chronic low back pain, partly due to lack of agreement about its definition. Chronic low back pain is mostly defined as persistent pain occurring on most days and lasting longer than 3 months (Maher 2004;Von Korff 1996; Waddell 2004) Others also define it as pain exceeding normal healing times and frequently reoccurring back pain over long periods. Acute and chronic LBP warrant separate consideration as they may respond differently to the same interventions. (Sierpina 2002; van Tulder 1999)

Causes[edit | edit source]

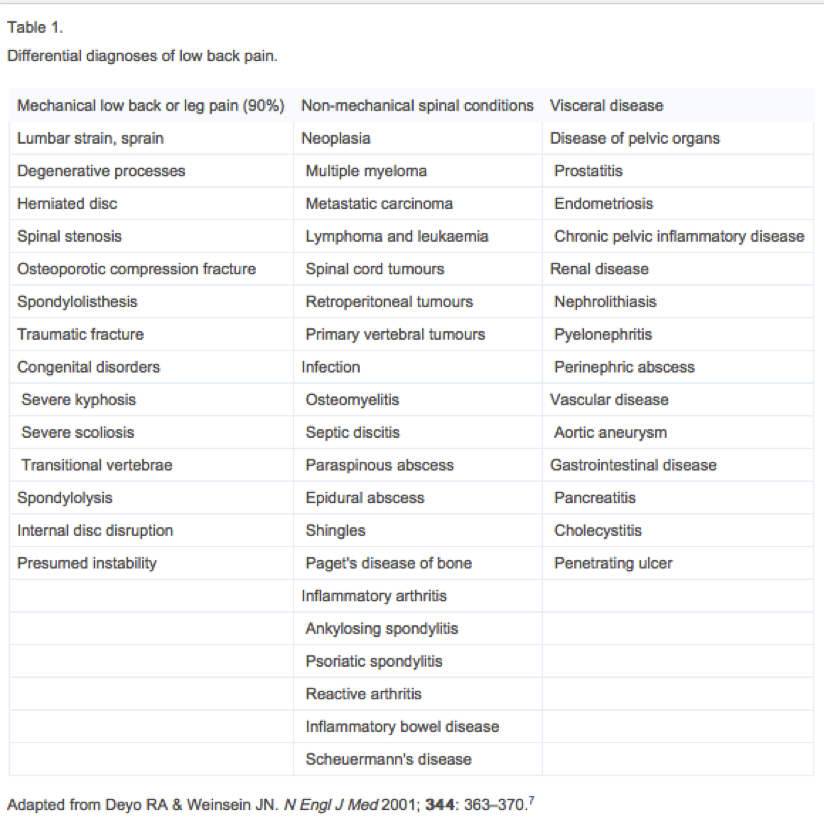

Mechanical disorders are the cause in 90% of cases with the remaining 10% of cases being due to manifestation of systemic illness (Nachemson 1976). Despite the large number of pathological conditions that give rise to low back pain cases 85% are without patho-anotomical or radiological abnormalities (Deyo and Weinsein, 2001). Most episodes of low back pain resolve quickly and are not incapacitating, nonetheless pain and disability are often ongoing and recurrences are common (Pengel et al. 2003). It is estimated 10 to 20% of effected adults develop symptoms of chronic low back-pain (Diamond and Borenstein, 2006).

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Many different patient characteristics have been described that predict who is at risk of developing chronic LBP. However, only a few have been replicated consistently in multiple studies. These include increasing age, previous back pain, job dissatisfaction, pain below the knee and depression. (Anderson 1999, Cherkin et al. 1999,Epping-Jordan et al. 1998) Depression has long been noted to be associated with various chronic pain syndromes, and several studies have reported it’s relationship with chronic back pain in particular in multiple studies (Epping-Jordan et al. 1998). Women are more commonly affected with LBP and some studies show increases in chronic LBP (Cherkin et al. 1999). Thomas et al. (1999) found that persistent back pain was associated with “premorbid factors” such as poor baseline functional status, high levels of psychological stress, poor self rated health, low levels of physical activity, smoking and obesity. Smoking has been found in multiple epidemiological studies to be a risk factor for the development of chronic low back pain (Deyo and Bass, 1989).

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The longer the patient suffers from back pain the worse the prognosis. The chance of low back pain resolving is its highest during the first week (Anderson 1999). By the end of year one that chance diminishes significantly. In Van den Hoogen et al. 1998's study on the course of low back pain, 35% patients had pain at 12 weeks and 10% of patients had pain at 1 year. Thomas et al. 1999 reported similar outcomes at 1 year with 10% of patients complaining of the same back pain form the first episode. Carey et al. 2000 found that 2/3 of patients with chronic low back pain at 3 months still had functionally disabling symptoms at 22months and only 16% of patients became symptom free. Most patients on disability for more than 6 months will not return to work. The number of patients returning to work approaches zero at 2 years (Anderson 1997). Once established, chronic low back pain is persistent and achieving complete remission becomes less likely as time goes by. The question remains how to treat chronic low back pain, and can you prevent it from occurring in the first place?

Core Stability[edit | edit source]

Definition

[edit | edit source]

Many authors have attempted to define core stability, which consequently means a globally accepted definition is yet to be confirmed (Huxel –Bliven and Anderson 2013). However, a widely accepted definition of core stability is:

“Comprises of the lumbopelvic-hip complex and is the capacity to maintain equilibrium of the vertebral column within its physiologic limits

by reducing displacement from perturbations and maintaining structural integrity.”

(Akuthota, Nadler 2004, Liemohn, Baumgartner, Gagnon 2005, Panjabi 2003, Panjabi 1992, Smith, Nyland, Caudill, Brosky, Caborn 2008, Willson, Dougherty, Ireland, Davis 2005)

History[edit | edit source]

The first acknowledgment of core stability was by Henry and Florence Kendall who were both Physiotherapist's and first developed the idea of a “neutral pelvis” in 1940/1950’s (Kent 2012).

They initially suggested that the surrounding superficial muscle groups were responsible for the maintenance of alignment and of “neutral spine” . The muscles they were referring to were the erector spinae, hamstrings, abdominals and the hip flexors. Following on from this, it was suggested that pelvic tilt was pelvic movement deviating from the neutral position.

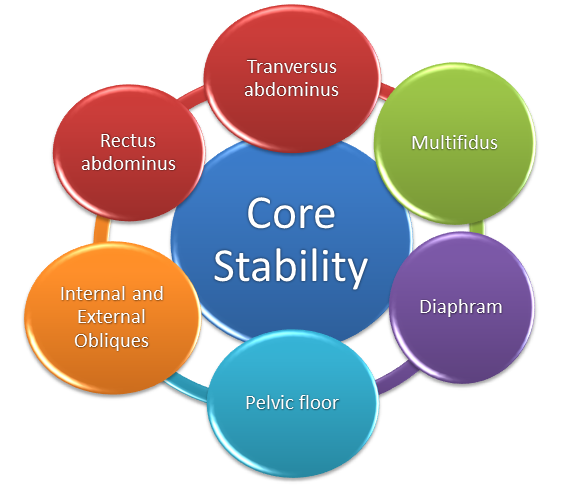

Over the years, the concept of core stability has changed and auhtors such as Paul Hodges have highlighted the significance and contribution of the Transverus Abdominus muscle, especialy in lumbo pelvic stability. Upon this basis, it has now become and important part in the management of spinal stability and exercises orientated upon the activation, recruitment and strengthening the core are a common avenue of treatment (Hodges 1999).

Theories and Applications, How does it fit in to the wider picture ?

[edit | edit source]

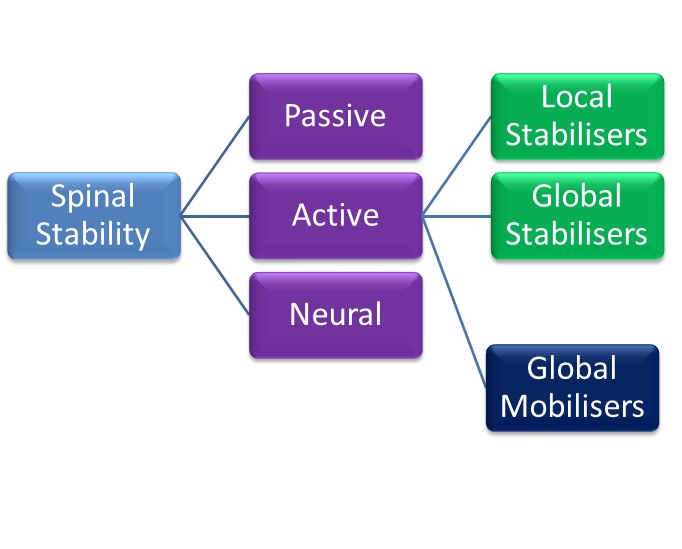

In attempt to add some clarity to the phenomena of the stabilisng system of the spine, Panjabi proposed a classification model which offered an explaination into the functioning of the spine. His model consisted of three categories (Panjabi 1992), Active, Passive and Neural and the evident importance of core stability can be seen.

Passive[edit | edit source]

The passive category consists of the basic components of the spine which allow for soft tissue attachment (Panjabi 1992).

• The lumbar vertebrae

• The joint capsules

• The intervertebral disc

• Ligaments surrounding the area

These structures of the spine do not contribute to any significant spinal stability in the neutral alignment. The skeletal structure does support the basic framework and the tensile properties in the various ligaments do start to resist end range movement, however do not have the capability to produce forces which initiate spinal movement is not caused by the passive structures.

Active[edit | edit source]

The active structures hold responsibility for the initiation of gross spinal movement as well as providing contributing to spinal segmentation.

Bergmark (1989) further classified the active system into the local and global stabilising system.

The local globalising system was slated to have a primary role in the mainatancence of spinal segement stability and stiffness.

The Global stabilising system was stated to be more superficial and with a primary function to generate force to control movement, there is often eccentric contractions to control motion segments throughout range

Global mobilisers

[edit | edit source]

A further active functional classification was suggested by Comerford and Mottram (2001). They have proposed the idea of “global mobilisers”. The primary role of these muscles is for shock absorption and to generate the gross spinal concentric contractions required for gross motor function.

Neural

[edit | edit source]

The neural component, according to Punjabi, is responsible for recieving information from the various transducers and relaying the relative signal onto the active system to achieve segmental stability. Until sufficient stability has been achieved, the neural components continue to control the active systems.

Figure 1. [edit | edit source]

A model showing the relationship between the three models proposed by Punjabi (1992), Comerford and Mottram's (2001) and Bergmark (1989), which influecne "spinal stability".

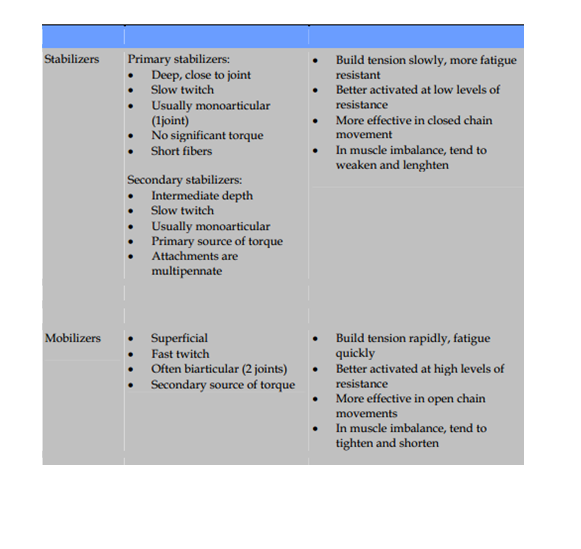

Figure 2.[edit | edit source]

A table proposed by Norris (2008), identifying the different characteristics between the stablisers and mobilisers.

(Norris 2008)

Relevant anatomy

[edit | edit source]

(Kibler, Press and Sciascia 2006)

Physiology

[edit | edit source]

It has been stated that core is characterised by “Proximal stability for distal mobility” (Putnam 1993, Zattara and Bouisset 1988)

When contracting, the primary role of the core stability muscles is to raise the intra-abdominal pressure and to increase the tension in the thoracolumbar fascia.

The increase in intra-abdominal pressure stiffens and strengthens the relevant structural support around the spine, compacts the arthrogenic structures and in combination with abdominal contraction, it can encourage a rigid cyclinder and stiffness to occur around the spine (McGill and Norman 1987).

This gives the spine a relative degree of stability which is needed to facilitate superficial muscle activation and gross motor action.

Core stability functions[edit | edit source]

• Anticipatory postural adjustments – pre-programmed muscle activation which helps the body to anticipate the subsequent force

• To create interactive moments that help to control the exposure of force and loading that is applied to a joint

• To help in force control throughout the various locations in the body

(Kibler, Press and Sciascia 2006)

Typical core exercises[edit | edit source]

A lumbo-pelivic stability programme is constructed in three sections (Richardson, Hodges and Hides (2004).

Section 1 - Entails segmental control and active recruitment over global mobilisers - specifically transversus abdominus, pelvic floor and diaphragm

Section 2 - Whislt maintianing segmental control and activation, introducing closed chain exercises, with low velocity and low load.

Section 3 - Whilst maintaining segmental control, introducing open chain exercises with high velocity and load. Movement of adjacent body segements can be used to stress the core structures

Many of the specific exercises listed below have been proven to significantly increase general health, sports functioning, and significantly decrease in pain.(Gladwell, Head, Haggar et al 2006)

Phase 2[edit | edit source]

Bridging

Single leg fall out

Single leg extension in supine

Basic 4 point Kneeling

Advanced 4 point Kneeling

The modified one leg stretch: Crook lying, slide one leg away as far as possible and then return to start position.

The modified shoulder bridge: Crook lying, “peeling” the bottom off the mat. Progression: Increase the range of movement (more of the spine away from the mat).

Swimming (a modification from a four point base): Box position, slide one foot along the floor behind, return to the start position. Repeat on other leg.

Phase 3.[edit | edit source]

Bridging progression onto a pilates ball

Pilates ball plank

Recent Evidence[edit | edit source]

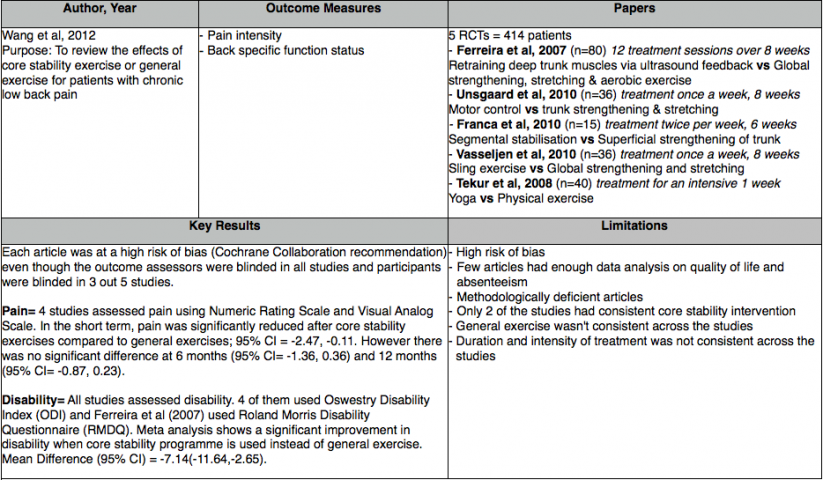

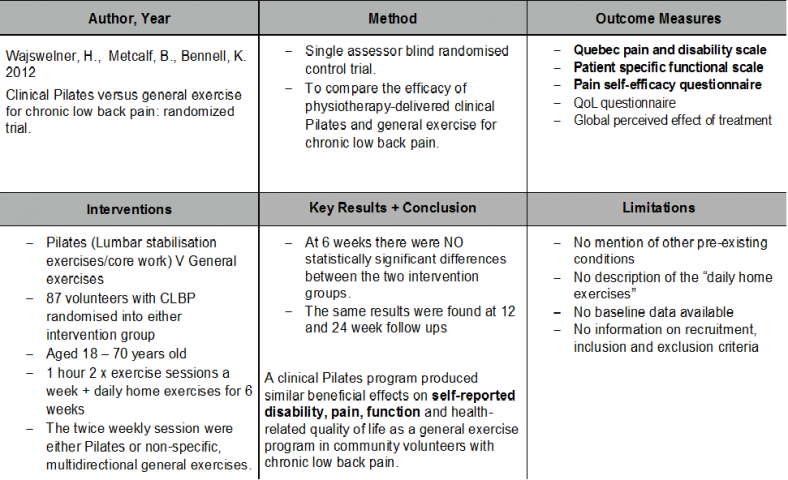

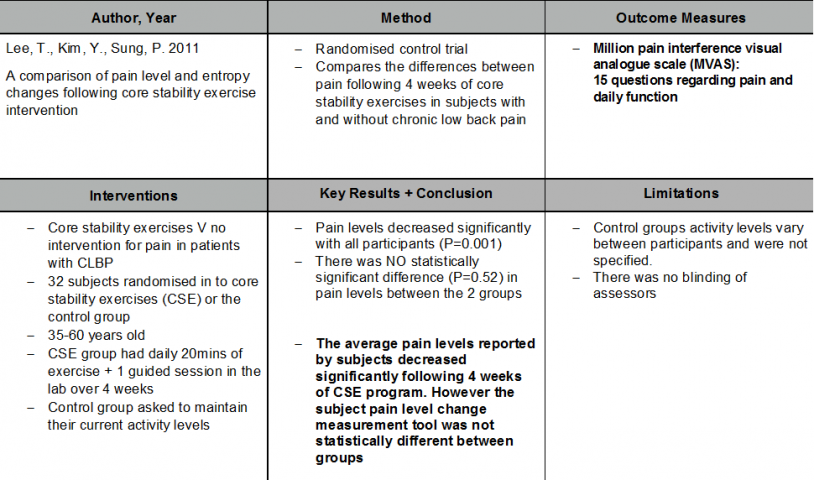

This chapter will look at the evidence which shows positive effects and ambiguity of core stability for chronic low back pain. The European Guidelines have stated that the following are recommended in the management of chronic non-specific low back pain: cognitive behavioural therapy, exercise therapy and educational therapy (Airaksinen el al, 2006). When searching the literature, studies only compared core stability exercise with general exercise therapy out of the European Guidelines recommendations.

Pain and function were selected as outcome measures to determine the effectiveness of core stability exercises as these were the consistent outcome measures in the evidence and have been shown to be major factor of psychosocial well-being of patients (Gureje et al, 1998; Stevens et al, 1996).

Evidence For

[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

Evidence Against[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The meta-analysis showed core stability exercise has signficant improvement in both pain and function compared to general exercise for patients with chronic low back pain. However these findings were only significant in the short term. In contrast, evidence published since this meta-analysis has found no significant difference between core stability and general exercises neither short term nor long term even though both interventions did improve pain and function. It should be noted though that no study reported adverse effects from core stability exercise when compared to general exercise with respect to pain and function.

In conclusion these findings show that clinicians have a choice to either administer core stability exercise or general exercise when a patient has chronic non-specific low back pain. Core stability exercise can be used as an alternative to general strengthening and stretching if patient is more suitable and if it would encourage compliance. However clinicians should not expect a significant improvement by choosing core stability in regards to pain and function especially in the long term.

Limitations

[edit | edit source]

The wealth of literature available compared core stability exercises to general exercise. Although there is literature to support the use of other therapies e.g. CBT, mobilisations and pharmacology they have not been compared directly to core stability exercises. Therefore further research is required into these areas.

References[edit | edit source]

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, Mannion AF, Reis S, Staal JB, Ursin H, Zanoli G. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006 Mar;15 Suppl 2:S192-300.

Akuthota, V, SF Nadler. Core strengthening, Archives of Physical Medical Rehabilitation, 2004, 85(3)(suppl 1):S86-S92.

Andersson, G. B. J. (1997). The epidemiology of spinal disorders. The adult spine: Principles and practice.

Bergmark, Anders. Stability of the lumbar spine:A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum, 1989, VOL. 60, NO. 230

Carey, T. S., Garrett, J. M., & Jackman, A. M. (2000). Beyond the good prognosis: examination of an inception cohort of patients with chronic low back pain. Spine, 25(1), 115.

Cherkin, D. C., Deyo, R. A., Street, J. H., & Barlow, W. (1996). Predicting poor outcomes for back pain seen in primary care using patients' own criteria. Spine, 21(24), 2900-2907.

Comerford, M. J, S. L. Mottram. Functional stability re-training: principles and strategies for managing mechanical dysfunction, Manual Therapy, 2001, 6(1), 3±14

Dagenais, S., Caro, J., & Haldeman, S. (2008). A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. The Spine Journal, 8(1), 8-20.

Deyo, R. A., & Bass, J. E. (1989). Lifestyle and low-back pain: the influence of smoking and obesity. Spine, 14(5), 501-506.

Deyo, R.A., Weinstein, J.N.(2001)Low back pain. New England Journal of Medicine;344(5):363–70.

Diamond, S., & Borenstein, D. (2006). Chronic low back pain in a working-age adult. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 20(4), 707-720.

Epping-Jordan, J. E., Wahlgren, D. R., Williams, R. A., Pruitt, S. D., Slater, M. A., Patterson, T. L., ... & Atkinson, J. H. (1998). Transition to chronic pain in men with low back pain: predictive relationships among pain intensity, disability, and depressive symptoms. Health Psychology, 17(5), 421.

Gladwell ,Valerie, Samantha Head, Martin Haggar And Ralph Beneke. Does a Program of Pilates Improve Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain? Journal of sports rehabilitation, 2006, 15, 338-350

Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. JAMA. 1998 Jul 8;280(2):147-51.

Hodges, P.W. Is there a role for transverus abdominus in lumbo-pelvic stability? Manual therapy, 1999, 4 (2), 74±86.

Huxel Bliven, Kellie C, Barton E Anderson. Core stability training for injury prevention, Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2013, Volume 5, 514.

Kent, Christine. The end of the “neutral pelvis” – part 1[online]. Albuquerque, 2012 [ 10/01/14]. Available from: http://wholewoman.com/blog/?p=1074

Kibler, Ben W, Joel Press and Aaron Sciascia. The role of core stability in athletic function, Sports medicine, 2006, 36(3): 189-98

Lee, T., Kim, Y., Sung, P. (2011) A comparison of pain level and entropy changes following core stability exercise intervention. International medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 17(7): pp.362-368

Liemohn, Wp, Ta Baumgartner, Lh Gagnon. Measuring core stability. Journal of Strength abd Conditioning Research/ National strength and conditioning association, 2005, 19(3):583-586.

Maher, C. G. (2004). Effective physical treatment for chronic low back pain. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 35(1), 57-64.

Mcgill, SM and RW Norman. Reassessment of the role of intra-abdominal pressure in spinal compression. Ergonomics, 1987, 30(11):1565-88

Norris, CM. Back Stability. Human Kinetics. Champaign, 2008,

Patel, A. T., & Ogle, A. A. (2000). Diagnosis and management of acute low back pain. American family physician, 61(6), 1779.

Panjabi, MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. Journal of Spinal Disorders. 1992, 5:390-396

Panjabi, MM. Clinical spinal instability and low back pain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2003, 13:371-379.

Pengel, L. H., Herbert, R. D., Maher, C. G., & Refshauge, K. M. (2003). Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. Bmj, 327(7410), 323.

Putnam, CA. Sequential motions of body segments in striking and throwing skills: descriptions and explanations. Journal of Biomechanics, 1993, 26 (1):125-35

Richardson CA, PW Hodges, J Hides. Therapeutic Exercise for Lumbo-pelvic Stabilization: A Motor Control Approach for the Treatment and Prevention of Low Back Pain. 2 edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Savigny, P., Watson, P., & Underwood, M. (2009). Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ, 338.

Sierpina, V. S., Curtis, P., & Doering, J. (2002). An integrative approach to low back pain. Clinics in Family Practice, 4(4), 817-831.

Smith, CE, J Nyland, P Caudill, J Brosky, DN Caborn. Dynamic trunk stabilization: a conceptual back injury prevention program for volleyball athletes. Journal of Orthopaedic Sports Physical Therapy. 2008,38:703-720.

Stevens SE, Steele CA, Jutai JW, Kalnins IV, Bortolussi JA, Biggar WD. Adolescents with physical disabilities: some psychosocial aspects of health. J Adolesc Health. 1996 Aug;19(2):157-64.

Thomas, E., Silman, A. J., Croft, P. R., Papageorgiou, A. C., Jayson IV, M., & Macfarlane, G. J. (1999). Predicting who develops chronic low back pain in primary care: a prospective study. Bmj, 318(7199), 1662-1667.

van den Hoogen, H. J., Koes, B. W., van Eijk, J. T. M., Bouter, L. M., & Devillé, W. (1998). On the course of low back pain in general practice: a one year follow up study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 57(1), 13-19.

Van Tulder, M. W., Koes, B. W., & Bouter, L. M. (1997). Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine, 22(18), 2128-2156.

Von Korff, M., & Saunders, K. (1996). The course of back pain in primary care. Spine, 21(24), 2833-2837.

Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Naghavi, M., Lozano, R., Michaud, C., Ezzati, M., ... & Brooks, P. (2013). Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2163-2196.

Waddell, G. (2004). The back pain revolution (Vol. 265482). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Wajswelner, H., Metcalf, B., Bennell, K. (2012). Clinical pilates versus general exercise for chronic low back pain: randomized trial. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 44(7): pp.1197-1205

Wang XQ, Zheng JJ, Yu ZW, Bi X, Lou SJ, Liu J, Cai B, Hua YH, Wu M, Wei ML, Shen HM, Chen Y, Pan YJ, Xu GH, Chen PJ. A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain.PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52082.

Willson, JD, CP Dougherty, ML Ireland, IM Davis. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. Journal of American Academy of orthopaedic Surgeons, 2005, 13:316-32