Telerehabilitation and Smartphone Apps in Physiotherapy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

===== Motivation ===== | ===== Motivation ===== | ||

Motivation | ===== Motivation ===== | ||

Motivation is complex term, and has been subjected to various definitions and approaches. Csikszentmihalyi<ref name="Csikszentmihalyi">Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The psychology of optimal performance. NY: Cambridge UniversityPress 1990</ref> defines motivation as “''a phenomenal experience being a sufficient reason for action''”, which then lead Deci and Ryan<ref name="Deci & Ryan 2000">Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55(1):68.</ref> to further develop its content focusing on the “functional significance of events” as the main determinant for motivation. | |||

In Self-Determination Theory, Deci & Ryan<ref name="Deci & Ryan 1985">Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. : Springer Science &amp; Business Media; 1985.</ref> separate motivation into types, centred on the different goals that lead to the development of an action: | |||

#'''Intrinsic motivation''', which denotes the act of doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable thus leading a person to act for the fun or challenge rather than because of external prods, pressures, or rewards. Spontaneous behaviours, which confer benefits to the organism, are not completed for any instrumental reason rather than constructive experience associated with exercising and empowering one’s capacities. | |||

#'''Amotivation''', which refers to the state of lacking an intention to act. Individuals who are amotivated lack intentionality and sense of personal causation due to the fact that they are not valuing an activity, not feeling competent to do it, or not believing it will lead to a desired outcome. | |||

#'''Extrinsic motivation''', which denotes the act doing something because it leads to a separable outcome: social demands and roles that require individuals to assume responsibility for non-intrinsically stimulating duties. It can be further defined into four categories: | |||

*''External regulation'', in which individuals perform tasks to satisfy an externally imposed demand. | |||

*''Introjection'', in which individuals perform tasks in order to avoid guilt or anxiety or to enhance self-esteem. | |||

*''Identification'', in which individuals identify the own importance of a behaviour, accepting its rules as his or her own. | |||

*''Integration'', in which individuals entirely assimilate rules and regulations and those are congruent with his or her own values and needs.<br> | |||

Motivation between individuals varies in amount, level (''how much?'') and orientation (''what type?''). Orientation of motivation refers to the essential attitudes and goals that lead to the development of a certain action (''why are we doing this?''). Research across various settings supports the role of communication in enhancing psychological functioning, self-regulation and intrinsic motivation. | |||

The ideal situation is that an individual is able to self-monitor himself because he truly believes in the intervention and knows how this is intrinsically important for him/her<ref name="Teixeira et al. 2012">Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Mata J, Palmeira AL, Markland D. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9(1):22.</ref> or because enjoyment of the activity leads to the adoption of a certain lifestyle<ref name="Cocosila et al. 2009">Cocosila M, Archer N. Adoption of mobile ICT for health promotion: an empirical investigation. Electronic Markets 2010;20(3-4):241-250.</ref>. If neither self-consciousness or enjoyment could lead an individual to change its behaviour towards a healthier lifestyle, family encouragement and family cohesion could determine better outcomes within the rehabilitation setting<ref name="Rosland et al. 2011">Rosland A, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2012;35(2):221-239.</ref>. | |||

The ideal situation is that an individual is able to self-monitor himself because he truly believes in the intervention and knows how this is intrinsically important for him/her | |||

===== Self-determination theory ===== | ===== Self-determination theory ===== | ||

Revision as of 21:58, 23 November 2015

Original Editor - Oriana Catenazzi, Alicia Rebellato, Hannah Meredith, Aaron Kirk, Martin Fitheridge, Marco Zavagni

Introduction to Telerehabilitation and smartphone physiotherapy applications

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to introduction

Learning Outcomes

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the learning outcomes

Table of Contents [edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the table of contents

Overview of Telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to diagnostic tests for the condition

Telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

In recent years, technology has revolutionised all aspects of medical rehabilitation, from developments in the provision of cutting edge treatments to the actual delivery of the specific interventions (Brennan et al. 2009). Telerehabilitation refers to the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to provide rehabilitation services to people remotely in their home or other environments (Brennan et al. 2009). Such services include therapeutic interventions, remote monitoring of progress, education, consultation, training and a means of networking for people with disabilities[1].

Using technology to deliver rehabilitation services has many benefits for not only the clinician but also the patients themselves. It provides the patient with a sense of personal autonomy and empowerment, enabling them to take control in the management of their condition (Brennan et al. 2009). In essence they are becoming an active partner rather than a passive participant in their care. It enables access to care for individuals in remote areas or for those who have mobility issues associated with physical impairment, access to transport and socioeconomic factors [1]. In addition, it cuts down the associated travel costs and time spent travelling for both the healthcare provider and the patient (Kairy et al. 2009). Research has found that the rehabilitation needs for individuals with long-term conditions such as stroke, TBI and other neurological disorders are often unmet in the patient’s local community [1].

As telerehabilitation expands, patient continuity of care improves. It enables clinicians to remotely engage and deliver patient care outside of the medical setting, thus eliminating the issue of distance between clinician and patient (Brennan et al. 2009). This opportunity to continue rehabilitation within the patient’s own social and vocational environment should lead to greater functional outcomes (Temkin et al. 1996).

The shift in the global demographics towards an increasing elderly population brings with it an associated increase in chronic health conditions (Dexter et al. 2010). This highlights the need for changes to be made in the delivery of rehabilitation services with the incorporation of self-management strategies and technology. In America, between 2005 and 2030, it is predicted that the number of adults over 65 years will increase from 37 million to 70 million or more (Institute of Med 2008). The figure below represents the predicted growth in the elderly population in the UK. It indicates that by 2035, individuals aged 65 and over will account for 23% of the total population (National Statistics 2012).

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/resources/percentolderpeopleuk19852010and2035_tcm77-258758.png

(National Statistics, 2012)

Growing numbers of elderly people have an impact on the NHS, incurring considerable health costs due to the growing demand for treatments (Cracknell 2010). It is hoped by integrating telehealth measures, these costs will be reduced. Kortke et al (2006) found a significant improvement in patient outcomes when using telerehabilitation and 58% reduction in cost in comparison to in-patient rehabilitation.

Generally, most systematic reviews that have been carried out investigating the efficacy of telerehabilitation report the patient’s perspective on its use as a positive experience with significant clinical outcomes (Rogante et al. 2010). The hope for the future is to continue to develop and use new, innovative technologies that will transform current practice and make telerehabilitation an integral part of healthcare [1].

Progression of technology[edit | edit source]

Telerehabilitation for physical disorders has been short lived. The problems that arose for this type of rehabilitation stemmed from the difficulties it imposed on the so-called “hands on” therapies, particularly physiotherapy and occupational therapy[1]. However, as technology has progressed in healthcare, the possibilities for effective telerehabilitation in therapies such as these has improved.

Figure 1. Progression of technology in telerehabilitation.

Early research into telerehabilitation was introduced with small pilot studies. In some of the first projects, clinicians used the telephone to provide follow up and to administer self-assessment measures (Korner-Bitensky and Wood Dauphinee 1995). From this, telerehabilitation continued to progress into the 1980’s with pre-recorded video material for client use and interaction (Wertz et al. 1992).

Eventually, live interactive video conferencing was introduced (Brennan et al. 2004). The potential uses for video conferencing in healthcare and telerehabilitation became apparent in the 1990’s with many projects being carried out in physiotherapy. In a randomised control trial (RCT) by Russell and colleagues (2011), the efficacy of this internet-based telerehabilitation system was assessed versus conventional physiotherapy in the provision of outpatient rehabilitation to patients who had received total knee replacement (TKR). Comparable results were reported with the two rehabilitation methods and patients were satisfied with the telerehabilitation treatment provided (Russell et al. 2011).

The use of videoconferencing allows for the provision of consultations, diagnostic assessments and delivery of treatment interventions as well as providing verbal and visual interaction between participants. However, problems lay initially in the inability to measure participant’s physical performance; for example in physiotherapy, these would include measures such as range of motion and gait. This was soon overcome by measurement tools that were able to objectively quantify participant’s physical performance [1]. Developments continued to be made using sensor and remote monitoring technologies for within the home which further enhanced the benefits of these new innovative technologies of telerehabilitation (Brennan et al. 2009). These developments provided a means of home-based exercise monitoring by the patient and the rehab professional while also enabling the professional to track patient compliance to specific exercise programmes (Zheng et al. 2005).

Virtual environments are another technological method introduced to healthcare. These allow users to interact with computer generated environments in real time [1]. Virtual reality begins with real world scenes which are then virtualized, thus mimicking real world environments (Cooper et al. 2001). It enables healthcare professionals to design environments which can be used in areas such as surgery, physical rehabilitation and education and training.

In recent years, smartphones have revolutionised communication within the medical setting. This modernisation is allowing the opportunity to provide medical support when and where people need it. Figure 2 below indicates the predicted growth in smartphone users in the UK up until 2017. Recently, it has been reported that half of smartphone owners use their devices to get health information (Boulos et al. 2014), with one fifth of smartphone users actually using health related applications (apps) (Fox and Duggan 2012). There are a wide range of mobile apps available for healthcare professionals, medical students, patients and the general public (Boulos et al. 2014).

Figure 2. Predicted growth in smartphone users in the UK

Applications for specific conditions[edit | edit source]

Scotlands Telehealth and Telecare delivery plan[edit | edit source]

The patient perspective on telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Key points[edit | edit source]

Understanding the patient[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Over the last decade the development and use of telehealth interventions for changing patient behaviours has greatly increased (Riley et al.2011). The use of mobile applications must take in account the physical and socio-psychological needs of health practitioners and patients. The user approaching a device, is not purely interested in what the device does, but rather how the device makes them feel: the developer must remember that the application is developed focusing on the customer and is designed to satisfy all their needs (Ruiz et al., 2012). The ability to access extensive and multifaceted programs provides health care professionals with the opportunity deliver behavioural change interventions that can be adapted to meet the patient’s characteristics, behaviours and environment (Patrick et al. 2008). In order to analyse the effectiveness of these interventions, health behaviour theories and models are used to guide the development and delivery of the intervention (Riley et al. 2011). Bandura’s Transtheoretical Model (bandura, 1982) and Self-Determination Theory (Prochaska and Velicer, 1999) have served as the basis for many health care interventions and it is important that the physiotherapist understands the underlying principles behind these theories. The use of health behaviour models and theories will assist the health care professional at the initiation stage of the intervention to meet their baseline characteristics of the patient and also during the intervention when behaviour change is taking place. To understand our patient fully it is necessary to examine their motivation, efficacy, and goals, then apply a theoretical model to our intervention.

Transtheoretical model[edit | edit source]

The TTM by Prochaska and Di Clemente (1983) consist of five stages related to changing individuals behaviour. Pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation are the motivational stages of the theory where the idea of changing behaviour varies from not at all to ready to change . These stages are followed by action and maintenance, during these stages the behaviour has been modified for less than six months and then established over the next six months. Depending on how the individual reacts to the process of change progression and regression between stages can occur. There are ten processes of change that need to be considered when changing behaviour and each can relate to specific stage in the model (Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente & Fava, 1988). These are the actions taken by the individual to develop a rationale for their changing behaviour it will help them overcome any potential barrier they may encounter in their pathway through the stages of change.

Table1. Transtheoretical model constructs (Glanz et al. 2008)

Table1. Transtheoretical model constructs (Glanz et al. 2008)

Prochaska et al. (1992) proposed that the effectiveness of the process of change will vary according to the individual's stage of readiness to change. From a physiotherapy perspective the processes of change could affect an individual’s behaviour towards an intervention in numerous ways. For example, consciousness raising will make the patient more aware of why they are performing the intervention, Self-liberation will provide the individual with the belief that committing or recommitting to an intervention will lead to behavioural change and to act on that belief (Glanz et al. 2008) and helping relationships such as the relationship between physio and patient will also help to facilitate change. These are just three of the ten processes of change and each process may have an impact on different stages of change. The aforementioned will affect the pre-contemplation, contemplation and action stages of the TTM.

Figure 4. The Transtheoretical model taken from Adams and White (2003)

Figure 4. The Transtheoretical model taken from Adams and White (2003)

Furthermore within the TTM there are different measures of behaviour that affect the individual's progression through the stages (Velicer et al. 1998). These measures include decisional balance , self-efficacy and temptation. The decisional balance aspect of the theory involves weighing up the pros and cons of changing. The use of self-efficacy within this model was adapted from Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (1982). It is defined as the confidence the individual has in their ability to cope with situations where a relapse is extremely likely. Temptation is the intensity of urges to engage in a specific behaviour when the individual is in a certain situation (Glanz et al. 2008). These concepts can be analysed by a temptation measure or a self-efficacy measure as both are similar in structure (Velicer, DiClemente, Rossi & Prochaska, 1990). These outcome measures are particularly useful in that latter stages of change and beneficial establishing why a relapse has occurred (Velicer et al. 1998). If we examine the model as a whole, the stages of change are the central construct of the TTM, the processes of change are theorised as independent variables, and decisional balance, self-efficacy and temptations are hypothesized as intermediate dependent outcomes (Velicer et al. 1998; DiClemente, 2003).

The TTM has been used with varying degrees of success across a wide range of interventions such as smoking cessation, diet, stress management, medication adherence, alcohol abuse and physical activity and has been used in a variety of settings including the home, community and workplace. In a review by Adams and White (2003) the researchers examined TTM interventions and physical activity adherence and found that within the literature, due to the nature of voluntary participants in the interventions the subjects who completed all follow up measurements were predominantly white, middle class, female, and regularly active despite having a more diverse population initially (Cardinal and Sachs 1994; Marcus et al. 1998; Paterson and Aldana 1999 Norris et al. 2000; Boch et al. 2001). This can undermine the reliability and validity of the results as it doesn’t take into account the persons from a lower socioeconomic groups and participants at the precontemplation stage who are the most likely to benefit from this type of intervention. For the TTM to promote inclusion it is necessary that all studies represent participants at all stages of activity not just those who are initially sedentary or already active (Adams and White, 2003). One of the other key findings from this review was that the interventions were more successful in promoting physical activity in the short term this was due to a limited number of studies measuring the effect of their intervention in the long term.

Existing literature has proposed that stage-based interventions such as the TTM are more successful than non-stage based interventions (Prochaska, DiClemente, Velicer & Rossi, 1993; Campbell et al., 1994). This has been scrutinised by more current literature concerning the effectiveness of this approach in changing health-related behavior (Bunton, Baldwin, Flynn & Whitelaw, 2000; Littell & Girvin, 2002). Therefore it is necessary to examine some of the reasons why the TTM may lack value.

The TTM was originally developed for addictive behaviours. A lack of evidence may be due to some behaviours being more suited to the TTM than others. This has been mentioned previously by Orford (1992) in relation to the TTM being more suitable to smoking interventions than to alcohol or drug use. Povey et al. 1999 also came to the conclusion that it is difficult to use with dietary interventions. Other authors have proposed that in order to accurately analyse the effectiveness of the TTM, behaviour change should not be the only focus of an intervention and the researcher should aim to influence alternative outcomes such as increases in knowledge in order to progress through the stages of change (Campbell et al., 1994; Cole, et al. 1998). Although this contradicts itself as the end result of stage progression is ultimately behavioural change (Clarke & Eves, 1997). Bridle et al. (2005) stated that a theory-driven interventions of behavioural change should take into account several essential features. There must be identification of an individual’s readiness to change. Once this has been established the intervention can be suited to that initial stage and all theoretical variables that the TTM hypotheses in order to enable stage progression. Following this the stage of change and other variables need to be continually assessed, and the intervention should be adaptive to the individual's readiness to change. This process should be replicated until a change in behaviour has taken place. Following the pathway will result in tailored interventions that react to individual’s progress through the different stages of change in the TTM (Bridle et al. 2005).

The TTM has been used in a telehealth setting previously via a mobile phone interventions. Obermayer et al. (2004) and Riley et al. (2008) who used text messaging (sms) interventions to promote smoking cessation and found 25% difference in participants who managed to quit smoking after six weeks using the same intervention and a similar patient age group. Therefore using the TTM could be beneficial for specific patient groups within a physiotherapy setting as long as the intervention develops as the patient progress through the stages of the model in order to develop the desired behavioural change.

The TTM and ICF framework The ICF framework takes into account all the biopsychosocial factors necessary for regaining health and is well established within physiotherapy practice. The use of behaviour change models, in particular the TTM, can coincide and relate to the ICF framework and as suggested by Riley et al. (2008) should be adapted to meet the needs of the individual over time. When a physiotherapist is implementing an intervention for a specific patient, the goals will be patient centred. Therefore the physiotherapist must understand what the needs of the patient and investigate these needs further and establish the barriers and facilitators which may present themselves during the intervention (Homa and Patterson, 2005). Once the appropriate subjective and objective examinations have been implemented the correct application and choice of techniques is imperative and there must be an assessment of whether or not the intervention has been successful (Homa and Patterson, 2005). As the patient is moving through the stages of change the ICF model will be used at each stage to ensure patient centred practice. It is important that we, as the physiotherapist look at all the biopsychosocial considerations before developing our clinical reasoning for a behavioural change intervention (Jelsma and Scott, 2011).

Self-efficacy theory[edit | edit source]

Self- efficacy theory was first proposed by Bandura (1982) it refers to an individual's sense of confidence in their ability to execute a specific behaviour in different environments (Bandura, 1997). An individual’s level of self-efficacy will depend on the amount of perseverance and effort applied to a specific behaviour (Bandura, 1982). The individual's view of their efficacy may shape their actions, effort and attitude (Bandura, 1977; Eysenck, 1978). An essential component of self-efficacy theory is that the stronger the belief a person has in their ability to perform a set of actions, the more likely they are to comply and maintain participation throughout an intervention. However, those who have an inferior amount of self-efficacy could apply less effort and have an increased chance of relapsing when trying to change their behaviour (Bandura and Cervone, 1983). Furthermore Bandura (1997) suggest that a person's level of self- efficacy is based on personal beliefs rather than objective assessments. Therefore a person’s beliefs can often predict their behaviour more accurately than their capabilities. This can result in a behaviour level that does not match the individual's capabilities and could be why behaviour between individuals varies even when they have similar understanding and skills set (Lee et al. 2008). It could then be argued that having self-efficacy alone could be sufficient enough to initiate a behavioural change (Bandura, 1997).

There are many barriers to self-efficacy especially in the elderly and vulnerable populations that telehealth interventions are designed for. Misunderstanding the ageing process among older adults may result in restricted activity levels (Lachman et al. 1997). Lack of knowledge about the benefits of exercise may produce a dismissive attitude toward participation towards interventions involving physical activity (King et al. 1992). More so, Supposed ill health and symptoms related to physical disabilities associated with chronic disease are reasons behind dropping out of an intervention (Clark, 1999; Lian et al. 1999). Within this population group many of the barriers to activity are attitudinal and we must use the self-efficacy theory in order to provide appropriate interventions that install confidence and believe in the individual to help them to modify their behaviour. (Lee et al. 2008).

Existing literature has concluded that self-efficacy-based interventions to improve physical activity levels had a significant effect on outcome measures such as distance walked among older adults (Allison and Keller, 2004) and improvements in physical activity levels (Allen, 1996), but not in self-efficacy itself. This could indicate that self-efficacy is not necessary for bringing change in physical activity behaviour. This has been further emphasised by Calfas et al. (1997) and McAuley et al. (1994) who also used theory based interventions and found no connection between self-efficacy and behavioural change. Another limitation with self-efficacy literature especially with physical activity interventions is the lack of reporting by the authors on the actual content of the intervention making it difficult to compare interventions and standardisation of behavioural change techniques (Ashford et al. 2010).

Conversely, physical activity interventions aiming to improve self -efficacy have improved confidence and the individual's adherence to physical activity interventions (Dunn et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2007). Existing research confirms that self-efficacy beliefs are critical in the initial adoption of an exercise routine (Lee et al. 2008). If the participant is able to believe that they can exercise under circumstances that could result in the relapsing behaviour it is more likely that they will take part in exercise intervention (Clark, 1996; Sallis et al. 1988). Therefore including self-efficacy theory in the design of physical activity intervention would be advantageous in guiding the participant towards adopting a new behaviour. Furthermore, In a systematic review by (Ashford et al. 2010) they found that self-efficacy was increased when the parts of the intervention was performed by a peer prior to the participant taking part and therefore knowing that another person was able to perform the activity gave the participants increased confidence in their own capabilities.

In summary self -efficacy is a vital component of behavioural change, confidence in one’s ability to perform a certain behavioural change intervention. Looking at self-efficacy from a physiotherapy perspective it would apply the same principles as the physical activity interventions mentioned above. Influencing beliefs and establishing barriers to interventions could be influential when developing a telehealth intervention. Self-efficacy could be essential in patients complying with any intervention that may be beneficial to their health including mobile applications aimed at a specific injury, a health condition or chronic pain intervention.

Motivation[edit | edit source]

Motivation[edit | edit source]

Motivation is complex term, and has been subjected to various definitions and approaches. Csikszentmihalyi[2] defines motivation as “a phenomenal experience being a sufficient reason for action”, which then lead Deci and Ryan[3] to further develop its content focusing on the “functional significance of events” as the main determinant for motivation.

In Self-Determination Theory, Deci & Ryan[4] separate motivation into types, centred on the different goals that lead to the development of an action:

- Intrinsic motivation, which denotes the act of doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable thus leading a person to act for the fun or challenge rather than because of external prods, pressures, or rewards. Spontaneous behaviours, which confer benefits to the organism, are not completed for any instrumental reason rather than constructive experience associated with exercising and empowering one’s capacities.

- Amotivation, which refers to the state of lacking an intention to act. Individuals who are amotivated lack intentionality and sense of personal causation due to the fact that they are not valuing an activity, not feeling competent to do it, or not believing it will lead to a desired outcome.

- Extrinsic motivation, which denotes the act doing something because it leads to a separable outcome: social demands and roles that require individuals to assume responsibility for non-intrinsically stimulating duties. It can be further defined into four categories:

- External regulation, in which individuals perform tasks to satisfy an externally imposed demand.

- Introjection, in which individuals perform tasks in order to avoid guilt or anxiety or to enhance self-esteem.

- Identification, in which individuals identify the own importance of a behaviour, accepting its rules as his or her own.

- Integration, in which individuals entirely assimilate rules and regulations and those are congruent with his or her own values and needs.

Motivation between individuals varies in amount, level (how much?) and orientation (what type?). Orientation of motivation refers to the essential attitudes and goals that lead to the development of a certain action (why are we doing this?). Research across various settings supports the role of communication in enhancing psychological functioning, self-regulation and intrinsic motivation.

The ideal situation is that an individual is able to self-monitor himself because he truly believes in the intervention and knows how this is intrinsically important for him/her[5] or because enjoyment of the activity leads to the adoption of a certain lifestyle[6]. If neither self-consciousness or enjoyment could lead an individual to change its behaviour towards a healthier lifestyle, family encouragement and family cohesion could determine better outcomes within the rehabilitation setting[7].

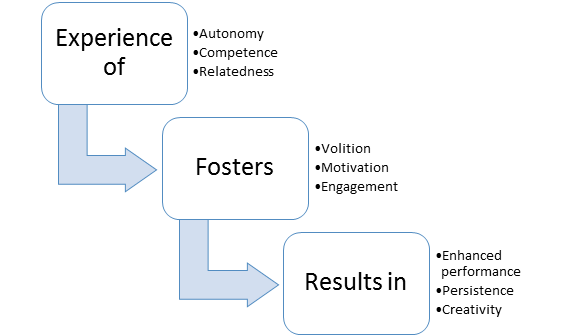

Self-determination theory[edit | edit source]

Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) is a macro‐theory of human motivation, personality development, and well‐being. The theory focuses especially on volitional or self‐determined behaviour and the social and cultural conditions that promote it. (Ryan et al. 2009)

Ryan and Deci (2000) propose three basic human needs involved in self-determination which motivate people to initiate behaviour:

1. Autonomy, which is the perception of experiencing a sense of choice and psychological freedom in the initiation of activities,

2. Competence, which is the ability to master challenges and the perception of being effective in dealing with the environment,

3. Relatedness, which is the sense of being cared for and connected to other people.

The quality of motivation is enhanced when any of these needs is satisfied, optimized if all three are satisfied and diminished if the person feels frustrated (Sanli et al., 2012).

A person’s motivation for an activity is a dynamic and constant continuum which development is based on certain aspects. External factors reduce feelings of autonomy thus prompting a shift from autonomous to controlled motivation or amotivation. On the other side, several other factors promote autonomous motivation (Visser et al. 2010).

Motivational states exist along this SDT continuum with amotivation (a state in which there is no intention to act) being the bottom form of motivation and intrinsic motivation (a state in which an action is performed for purely joy and interest of the activity itself) being the top form.

Extrinsically motivated behaviors, cover the continuum between amotivation and intrinsic motivation, varying in the extent to which their regulation is self-determined. These include external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation and integrated regulation. Externally regulated motivation (i.e., the least self-determined form of extrinsic motivation) results in behaviors performed to obtain rewards (e.g., praise, monetary compensation) or to avoid negative consequences (e.g., criticism from others).

Goal setting[edit | edit source]

The Aristotelic theory of final causality, in which every action is caused by a purpose, is the basic connection between Ryan and Deci (2000) SDT Theory and Locke (1996) Goal-Setting theory.

“A Goal is the object or the aim of an action” (Locke, 1996)

Goals have both internal (ideas) and external (object or condition to which they refer) aspects.

Goals help individuals to serve their dispositional desires, channelling them in a more concrete direction to be satisfied in an effective and efficient manner: internal aspect guides action to attain the external, desired state. (Ryan and Deci 2002).

Goals vary in content (the inner object) and intensity (the scope, focus of the selective process).

Locke et al. (1996) demonstrated the goals vary qualitatively (the goal content is what the person is seeking) and quantitatively (difficulty and specificity influence the content of a goal), summarizing that:

The more difficult the goal, the greater the achievement

The more specific or explicit the goal, the more precisely performance is regulated

Goals that are both specific and difficult lead to the highest performance and commitment.

Commitment to goals is attained when the individual is convinced that the goal is important and attainable.

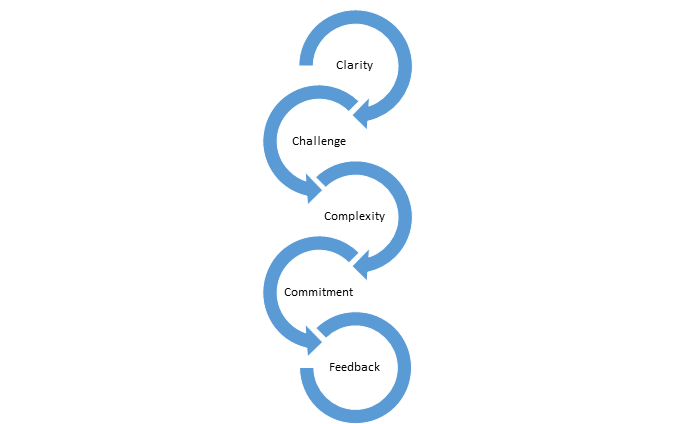

To underlie the importance of setting specific and difficult goals that, with feedback, lead to higher performance, Locke developed 5 fundamentals principles that constitutes an effective goal setting:

• Clarity: Goals are measurable and unambiguous. There should be no misunderstanding regarding which behaviours will be rewarded.

• Challenge: Goals are challenges. If a task is too easy, don’t expect the accomplishment to be significant.

• Complexity: if Goals are highly complicated, make sure that the individual won’t fight in the face of overwhelming odds.

• Commitment: Goals acceptance implies effort, over time, towards the accomplishment.

• Feedback: provides knowledge on progress towards the Goals.

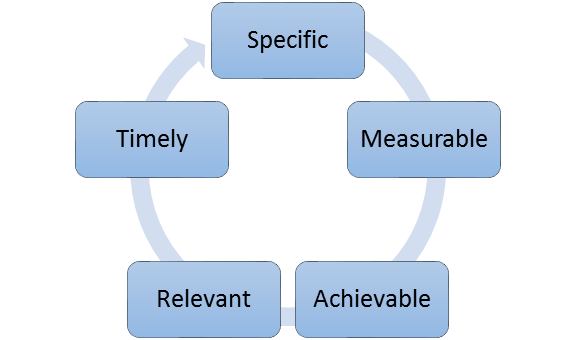

In 1981, Doran published an article titled “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives” in which described a new criteria on how to write meaningful objectives. The article underlined that goals, to be effective, should be relevant to the person involved, challenging but still achievable and realistic, and specific in order to be measured:

S.M.A.R.T. goals are used everyday in rehabilitation settings, even if difficult to develop and time-consuming (Bovend'Eerdt et al. 2009). In fact, despite the SMART acronym it clearly derives from the Goal Setting Theory and it is routinely used by physiotherapists, there is little research on how to develop the best goal setting. Some limitations could arise:

Specific, but changeable!

Measured, by patient or by health carers or by both?

Achievable, but may still be challenging!

Relevant, to whom?

Time, limited by who?

Clinical implications[edit | edit source]

Maclean et al. (2000) investigated the role of motivation in clinical settings, stating its importance in determining patient outcomes and underlying the difficulties encountered when promoting its development. To increase patient’s motivation, the authors suggest:

Goal setting (clear and revisable), including patient feelings and point of views (which should be accepted and respected)

Accept patient’s idiosyncrasies and worth patient’s value system

Have a warm, approachable and competent manner

Remind the patient that goals exist beyond the ward setting

Do not stress the responsibility for motivation and recovery merely on the patient

Future research could focus on improving our telehealth behaviour interventions but also our theoretical and practical understanding of health behaviour change (Riley et al. 2008). However, from the research associated with specific models as a theoretical basis for other types of intervention there is generally an improvement in patient behaviour. In the development of applications is important that we can tailor the intervention to suit the individual and are able to SMART set goals, motivate and ensure progression through behaviour change models in the short term as well as in the long term.

Research[edit | edit source]

Current smartphone applications and modernization of physiotherapy

[edit | edit source]

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

Current physiotherapy applications[edit | edit source]

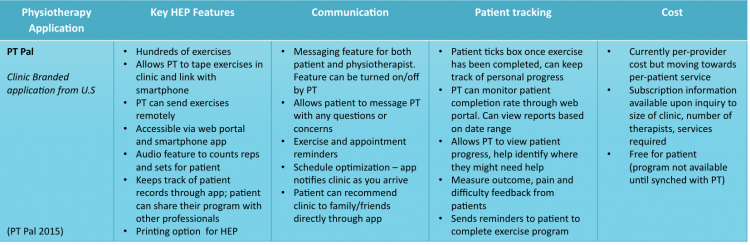

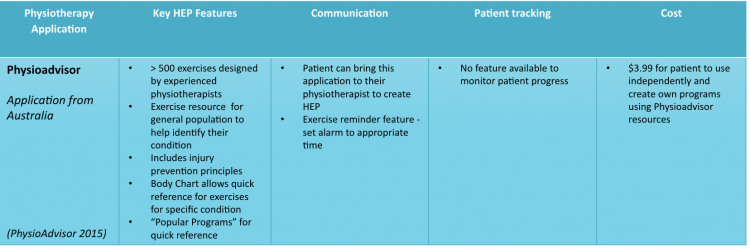

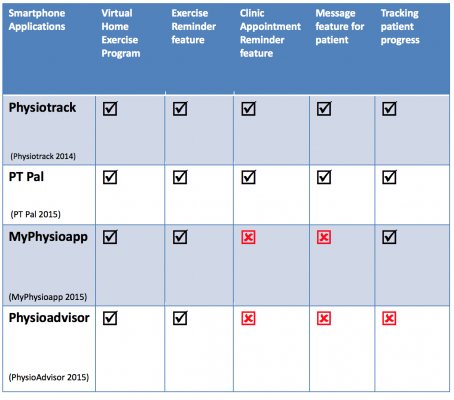

The following table compares key features of four different smartphone applications used worldwide in the creation and training of the home exercise programme (HEP) for the patient. Descriptions of their key HEP features, communication outlets, tracking/ reports and costs are outlined below.

PT Pal is a HIPPA compliant smartphone application launched in 2013 that was designed as a patient-centered approach to increase patient compliance with home exercise programs. Naveen Khan, a patient who was having difficulty adhering to her own physiotherapy program, is the founder and CEO of PT Pal. The application includes an exercise database for allied health professionals including Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists and Speech and Language Therapy. This application is constantly expanding and caters to multiple patient groups such as adult, paediatric, cognitive, specific care such as hip and knee as well traumatic brain injury. For the purpose of this wiki we will be discussing the app’s use for general musculoskeletal injuries for adults in physiotherapy practice.

PT Pal is an application that aims to solve patient non-compliance by storing, tracking and scheduling a patient's physical therapy exercises.

Physioadvisor (Physioadvisor 2015)

PhysioAdvisor is a website service and smartphone application designed by experienced physiotherapists and provides a comprehensive range of physiotherapy and injury rehabilitation exercises. The website was launched in 2008 and the first version of the application was launched in 2010. The application provides over 500 exercises and 800 images useful for the general musculoskeletal population. The application was designed as a reference for all ages, patients, athletes, physiotherapists and other health professionals. Exercises are grouped into strengthening, flexibility, pilates, popular programs, balance, swiss ball, foam roller, resistance band and massage ball exercises. The PhysioAdvisor website expresses that the "PhysioAdvisor Exercises" is one of the top selling Health & Fitness apps in Australia (PhysioAdvisor 2015).

Further considerations: Improved communication [edit | edit source]

Facilitating patient-provider relationship[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy smartphone applications, which aim to support home exercise programs can help further engage the patient throughout treatment. In healthcare, the term compliance is often defined as the 'patient's behaviours (in terms of taking medication, following diets or executing lifestyle changes) that coincide with healthcare providers' recommendations for health and medical advice' (Jim et al. 2008). For the purpose of this discussion, research often uses the term compliance to relate to patient adherence to a program, however we will use the term patient participation as a more engaging term.

As mHealth continues to evolve, it is predicted that it will provide the foundation to support self-management, health monitoring, self-directed learning and interactive patient-clinician communications into the future (Dicanno et al. 2015). All of the applications described above facilitate self-management through interactive user face to effectively communicate and deliver exercise programs to the patient. This feature allows the intervention the potential to be more effective by engaging in contextual sensitivity. This is the ability of the technology to shape the intervention based on unique circumstance or the individual's environment (Dicianno et al. 2015). Physioadvisor is one of the most simplistic applications in terms of communicated exercises as it uses a database of more than 500 exercise and 800 images, targeted to the patient directly by the recommendations created through the application The patient can also bring this application to their physiotherapist where the physiotherapist can then tailor exercises through the app (PhysioAdvisor 2015).

PT Pal, Physiotrak and MyPhysioapp incorporate a more interactive environment where the physiotherapist has the option to film the patient demonstrating exercises in clinic and upload directly to their program through the application, in addition to having access to a full database of preloaded exercises. Exercises on each device provide clearly written and verbal instruction for enhanced clarity. If an exercise is not included in any of these applications, a request can be sent directly to the company and they will update the application accordingly. The patient-prescriber relationship is a strong predictor of patient participation throughout treatment and a healthy relationship is built on trust in healthcare professionals (Jim et al. 2008). Physiotherapy exercises prescribed through mobile technology can facilitate this relationship by actively engaging the patient with more memorable individualized programs. Research has identified that too little time spent with patients is likely to threaten a patient's motivation to maintain therapy (Jim et al. 2008). These applications offer a tangible solution by providing an interactive exercise environment in between sessions.

Utilising reminder services to enhance communication[edit | edit source]

There are several issues with therapeutic non-compliance, including two major clinical issues concerning effect on treatment outcomes and increased financial burden for society (Jin et al. 2008). A significant contributing factor to therapeutic non-compliance is the failure to attend scheduled appointments. Research has documented several characteristics contributing to this absenteeism including demographic variables, family responsibility, ethnicity and religion (Collins et al. 2013). For the purpose of this discussion, we will only consider the most common reason for not attending appointments, which is forgetfulness (Chen et al. 2007; Geraghty et al. 2008, Collins et al. 2013). If the reader would like to further follow up on reasons why outpatients fail to attend their scheduled appointments, please follow this link here. It has been implied that SMS (short message system) reminders can play a role in reducing non-attendance at out-patient clinics (Geraghty et al. 2008). Additionally, researchers have tested the use of SMS across different preventative health behavior interventions and suggested its usefulness to provide patient education, appointment reminders, behavioural interventions, data acquisition and communication between patient and healthcare provider (Bouhaider et al. 2013). Taking in consideration the applications presented in our review, only PT Pal and Physiotrack will be critically discussed in this section, as they both offer reminder and message services for the patient. The application MyPhysioapp offers the patient the option to set up exercise reminders, however it does not mention appointment reminders. The message feature appears to benefit the physiotherapy practice, where the clinician is able to send 'push messages' to the patient's phone to inform them about available services, send promotions or links to their website. There is an option for the physiotherapist to incorporate personal comments on the patient program, which the patient receives on the application (Myphysioapp 2015). This application is clinic branded and offers the patient easily accessible contact details for the clinic through the main app page. MyPhysioapp describes this feature as an opportunity for patients to share the clinic details with friends and family to increase referrals to the clinic. Alternatively, Physioadvisor offers exercise reminders, however since the application is designed primarily as a reference for patients seeking their own information, there is no feature to link reminders with clinic appointments or option to message your physiotherapist (Physioadvisor 2015).

PT Pal has several embedded features to facilitate patient appointment efficiency. Features include incorporating reminder feature in your smartphone for appointment times, but also a schedule optimization feature for better service to patients. This feature allows the clinic to prioritize patients and call you in the event of an appointment opening up (PT Pal 2015). Providing clear information is important as many patients state that lack of understanding is a reason for not attending appointments (Colins et al. 2013). Similarly, PhysioTrack sets reminders to the patient's phone for appointment adherence. The website marketing specifically promotes the ability of this app to reduce cancellations (Physiotrak 2014). Both of these applications incorporate a reminder system embedded in the smartphone's calendar. Several studies have shown the use of SMS reminders to play positive role to play in reducing non-attendance at out-patient clinics (Chen et al. 2007). Literature focuses on the SMS feature found across many apps, but limited research is available concerning embedding reminders in smartphone calendar systems. For the purpose of this discussion, they will arguably apply similar outcomes, as they offer pop up reminder to attend an appointment. Research is also lacking into physiotherapy musculoskeletal outpatient clinics, as one review looked specifically across 10 major clinical domains including Activities of Daily Living, Alzeheimer's/Dementia care, Chemotherapy symptom management, palliatiave care management, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, falls and falls risk, osteoarthritis and dermatology (Geraghty et al. 2008). SMS reminders appear to have a significant impact on adherence to appointments and would be relevant to physiotherapy musculoskeletal outpatient clinics. Additionally, the use of SMS and increased communication between the patient and physiotherapist can further benefit patient participation in a rehabilitation program. Both PT Pal and PhysioTrack allow the physiotherapist to message the patient through the application to see check in on their efforts. Alternatively, the patient can also respond and send messages to their physiotherapist if they have any questions or concerns. Both systems send messages using push notifications through their software, however Physiotrack also mentions sending an SMS or e-mail as an alternative if the message can not be received by the patient.

This is an important feature as tailored health messages are more engaging and effective at changing behavior than untailored, bulk messages (Fjeldsoe et al. 2009). Recent research has identified that text-messaging improves outcomes in a outpatient cardiovascular rehabilitation setting. In this study, text messages were sent 3-5 times weekly and consisted of heart-healthy tips, requests for weight and BP input and minutes of exercise per day as well as medication adherence (Lounsbury et al. 2015). Results from this study indicated that the addition of SMS is cost-effective and significantly improves outcomes and compliance alongside a traditional cardiorehabilitaiton program (Lounsbury et al. 2015). Historically, SMS represents the most frequently used mobile phone feature in research focused on the role of mobile phones as a tool for encouraging and monitoring health, with much of this literature is specifically centered on diabetes management and weight loss (Monroe et al. 2015). Text messages were most often used to send motivational messages, educational information, social support and for self-monitoring (Monroe et al. 2015). It would be beneficial to identify research supporting these physiotherapy applications and the future ways that physiotherapy smartphone applications can incorporate messages to stimulate behavior change. PT Pal has several ongoing studies that will be published in the upcoming year (Catenazzi 2015).

Facilitating Knowledge and Education through Physiotherapist communication[edit | edit source]

Another strong predictor on patient participation in healthcare is effective patient knowledge about their condition and course of action. Patient education is extremely important to enhance therapeutic compliance and healthcare providers should supply patients with adequate education about their treatment and disease (Jin et al. 2008). All of the smartphone applications discussed provide additional resources relevant to the patient's condition. PhysioTrack is partnered with the University of Dublin and SportEx to keep up to date with relevant research protocols. Additionally, PhysioTrack allows physiotherapists to send their patient relevant information and research about their condition (Physiotrack 2015). Similarly, MyPhysioapp allows physiotherapists to provide their patients with relevant health topics like diagnosis, self-management concepts and general health literacy (MyPhysioapp 2015). PT Pal is partnered with various hospitals to stay up to date on clinical protocols and has recently appointed a clinical advisor, Dr. Russel Carter to their team (PT Pal 2015). This allows the application to communicate up to date research with their clients (Catenazzi 2015). Lastly, PhysioAdvisor incorporates additional information through an injury profile library to help inform and educate patients (Physioadvisor 2015). Education for patients is important as many patients describe not attending appointments because they perceived that their appointment was unnecessary. Providing clear information to patients is important since many patients appear to lack understanding over their own healthcare (Collins et al. 2007). Communicating relevant information about the patient's condition can further engage the patient in his or her own treatment concerns and builds a greater understanding and partnership with the physiotherapist.

Communicating the right exercise prescription[edit | edit source]

Finally, the importance of communicating the appropriate exercise prescription in an interactive manner is discussed. mHealth applications creates new opportunities for patients to strengthen their relationship with their therapist, reinforce standing of the plan of care, confirm home exercise techniques and proactively address relevant concerns (Dicanno et al. 2015). As previously mentioned, all of the physiotherapy smartphone applications that are discussed here offer detailed individualized exercise programs to increase patient participation in the home exercise program. All applications offer clear images and descriptions for easy-to-understand explanations of how to perform the exercises.

PT Pal is arguably the most interactive device of them all as the exercise programs offers an audio option to count sets and reps as well as overall duration of the program. In addition to this, pop-up motivational notifications can inform a patient when they are almost done their exercises (PT Pal 2015). Importantly, PT Pal has the feature to collect pain and difficulty feedback from patients to help tailor exercise prescriptions and adapt programs in real time. When asked how physiotherapists have responded to using the app, Naveen Khan has stated:

“They love it. They feel like it's quicker, they got feedback that they've never gotten before. Often, the physiotherapist will give too many or not enough and they might hurt, so the app lets the patient give the clinician some feedback and they can react on it, so it's more personalized thoughtful care" - Naveen Khan, CEO and founder of PT Pal

Rehabilitation professionals can utilize this information to better understand any relevant environmental factors affecting exercise adherence as well as utilizing this real time data to receive patient feedback that is less subjective to recall bias in future appointments (Dicianno et al 2015). Physiotherapists' who use PT Pal can monitor patient progress remotely and send reminders or follow up notes to patients who may not be completing their program or appear to be having difficulty (PT Pal 2015). The patient confirms (with a click of the box) once an exercise is completed, allowing the patient to keep track themselves. Additionally, the physiotherapist is notified with highlighted coloured button of red, yellow or green informing the physiotherapist of the patient’s status with the HEP (Catenazzi 2015). Additionally, the patient who uses PT Pal has their program stored in the application which they can share with other health professionals. In this way, it keeps all health professionals informed on the quality of care and they can work together remotely (Catenazzi 2015). PT Pal is continually evolving and targeting the application to more health professionals (PT Pal 2015)

Similarly, MyPhysioapp also requests the patient's current symptom using a VAS scale (1-5) once they start their program. The application incorporates timed sets, reps and rest intervals. Upon completion of the program, the patient has the option to write any relevant notes or comments on their personal progress. The patient can then use this information to track progress and monitor their symptoms over the duration of their physiotherapy program (MyPhysioapp 2015). In comparison, Physiotrak stores the patient's exercise prescription history and offers a 'compliance button' for the patient to track when they complete their exercises (Physiotrak 2014). This information is sent directly to the physiotherapist's portal where they can monitor patient's progress. Physiotherapists have the option to track the patient's progress with a reporting feature on their account. As we have evaluated, PhysioAdvisor does not offer any reporting option or tracking program to monitor patient compliance with the program.

An important feature for patient participation in healthcare is accessibility and satisfaction with the healthcare facilities (Jin et al 2008). These physiotherapy applications helps to promote healthcare facilities remotely in the patient's own environment. An important feature of the application is that is must be useful and usable, and this may link with adoption and frequent use of mobile application (Monroe et al. 2015). If the physiotherapist is able to communicate effectively with the patient about their condition, treatment and home exercise options using any of these applications, there will likely be improved patient participation and engagement with their rehabilitation process.

Further considerations: Facilitating behaviour change[edit | edit source]

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation towards rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Self-efficacy and goal setting[edit | edit source]

Cost effectiveness[edit | edit source]

The common occurrence of patients’ failing to attend scheduled appointments is estimated to cost 65 pounds per incidence. This results in underutilization of the healthcare system as well as prolonged waiting lists (Geraghty et al. 2008). A smartphone application is a potential method to prevent cancellations through effective reminder systems. Each application costs a small renewable fee which is based on the number of physiotherapists and or clinics that require subscription (except for Physioadvisor which is a one time nominal fee for the patient). Important to note is that therapeutic non-compliance has been associated with excess urgent care visits, hospitalizations and higher treatment costs (Jim et al. 2008). These applications can be seen as an investment for the clinic to help increase clinic efficiency, reduce cancellations and prevent future health care demand. The Scottish Government understands this priority and accepts the relevance of such applications as ways to manage rising costs and demand as mentioned in the National Delivery plan (The Scottish Government 2012).

Scotland has started to recognize the way forward with ‘Scotland’s Digital Future’ and its benefits by providing a significant investment in telehealth. NHS 24 continues to work with NHS boards to develop the use of healthcare in all health-related areas (The Scottish Government 2011). While these applications provide an exciting new outlet for Physiotherapy to proceed towards in the future, there are some barriers and limitations to the successful implementation of these new technologies. Through a discussion and understanding of these obstacles, further research can be directed at ways to improve and adapt technologies to suit the current needs of healthcare.

Limitations

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the limitations

Concluding Remarks [edit | edit source]

With the ever enhancing realm of technology and mHeath applications, the future generation of physiotherapists must be aware of the evolving changes in technology to make physiotherapy an interactive environment with the patient. This will support an increase in motivation and facilitate participation in a home exercise program. As one review discovered, non-compliance remains a major issue in improving healthcare outcomes despite many studies highlighting this ongoing issue over the years (Jin et al. 2008). The new face of physiotherapy applications can facilitate patient adherence by creating an interactive exercise environment that promotes self-efficacy and behavior change through enhanced communication, goal setting and progress reporting means. As this wiki has highlighted, there are many links that can be made between the models of behavior change and some of the smartphone applications discussed here, however due to wide variation in terms of study designs and applications, it is difficult to pinpoint potential influences of mobile-phone based strategies on physical activity behavior (Monroe et al. 2015). Additionally, the effectiveness of smartphone applications to improve health behaviours is an emerging field of research (Kirwan et al. 2012). As the Scottish Government highlights for our way forward, we need to improve sustainability and value by establishing a baseline, and developing consistent outcome measures and indicators to track the impact of telehealth and telecare on working practices, productivity and resource use (The Scottish Government 2014). Future research is necessary to focus on these novel physiotherapy applications and the effect on patient behavior change and patient experience. Research should also target physiotherapy programs administered via these applications to identify any advances in rehabilitation and home exercise programs. As the Scottish Government identifies, we need to raise awareness, publish and promote innovative approaches, good practice and illustrate user/patient experiences to further develop good practice (The Scottish Government 2014). The physiotherapy smartphone applications discussed in this wiki page have identified a new and emerging area in physiotherapy to better our practice and further facilitate the patient-physiotherapist relationship. The list of smartphone physiotherapist applications is not exhaustive, and many other applications currently exist and will be created in the future. The information presented here should allow the reader to identify key features provided in smartphone applications that may enhance the physiotherapist-patient relationship. Physiotherapists need to be aware of the expanding significance of telerehabilitation as new technology might offer further support to our patients.

CPD Test your knowledge [edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 THEODOROS, D. and RUSSELL, T., 2008. Telerehabilitation: current perspectives. Vol. 131, pp. 191-209.

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The psychology of optimal performance. NY: Cambridge UniversityPress 1990

- ↑ Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55(1):68.

- ↑ Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. : Springer Science & Business Media; 1985.

- ↑ Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Mata J, Palmeira AL, Markland D. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9(1):22.

- ↑ Cocosila M, Archer N. Adoption of mobile ICT for health promotion: an empirical investigation. Electronic Markets 2010;20(3-4):241-250.

- ↑ Rosland A, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2012;35(2):221-239.