Telerehabilitation and Smartphone Apps in Physiotherapy: Difference between revisions

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

===== Clinical implications ===== | ===== Clinical implications ===== | ||

Maclean et al. (2000) investigated the role of motivation in clinical settings, stating its importance in determining patient outcomes and underlying the difficulties encountered when promoting its development. To increase patient’s motivation, the authors suggest: | |||

•Goal setting (clear and revisable), including patient feelings and point of views (which should be accepted and respected) | |||

•Accept patient’s idiosyncrasies and worth patient’s value system | |||

•Have a warm, approachable and competent manner | |||

•Remind the patient that goals exist beyond the ward setting | |||

•Do not stress the responsibility for motivation and recovery merely on the patient | |||

Future research could focus on improving our telehealth behaviour interventions but also our theoretical and practical understanding of health behaviour change (Riley et al. 2008). However, from the research associated with specific models as a theoretical basis for other types of intervention there is generally an improvement in patient behaviour. In the development of applications is important that we can tailor the intervention to suit the individual and are able to SMART set goals, motivate and ensure progression through behaviour change models in the short term as well as in the long term. | Future research could focus on improving our telehealth behaviour interventions but also our theoretical and practical understanding of health behaviour change (Riley et al. 2008). However, from the research associated with specific models as a theoretical basis for other types of intervention there is generally an improvement in patient behaviour. In the development of applications is important that we can tailor the intervention to suit the individual and are able to SMART set goals, motivate and ensure progression through behaviour change models in the short term as well as in the long term. | ||

Revision as of 18:29, 23 November 2015

Original Editor - Oriana Catenazzi, Alicia Rebellato, Hannah Meredith, Aaron Kirk, Martin Fitheridge, Marco Zavagni

Introduction to Telerehabilitation and smartphone physiotherapy applications

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to introduction

Learning Outcomes

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the learning outcomes

Table of Contents [edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the table of contents

Overview of Telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to diagnostic tests for the condition

Telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Progression of technology[edit | edit source]

Applications for specific conditions[edit | edit source]

Scotlands Telehealth and Telecare delivery plan[edit | edit source]

The patient perspective on telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Key points[edit | edit source]

Understanding the patient[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Over the last decade the development and use of telehealth interventions for changing patient behaviours has greatly increased (Riley et al.2011). The use of mobile applications must take in account the physical and socio-psychological needs of health practitioners and patients. The user approaching a device, is not purely interested in what the device does, but rather how the device makes them feel: the developer must remember that the application is developed focusing on the customer and is designed to satisfy all their needs (Ruiz et al., 2012). The ability to access extensive and multifaceted programs provides health care professionals with the opportunity deliver behavioural change interventions that can be adapted to meet the patient’s characteristics, behaviours and environment (Patrick et al. 2008). In order to analyse the effectiveness of these interventions, health behaviour theories and models are used to guide the development and delivery of the intervention (Riley et al. 2011). Bandura’s Transtheoretical Model (bandura, 1982) and Self-Determination Theory (Prochaska and Velicer, 1999) have served as the basis for many health care interventions and it is important that the physiotherapist understands the underlying principles behind these theories. The use of health behaviour models and theories will assist the health care professional at the initiation stage of the intervention to meet their baseline characteristics of the patient and also during the intervention when behaviour change is taking place. To understand our patient fully it is necessary to examine their motivation, efficacy, and goals, then apply a theoretical model to our intervention.

Transtheoretical model[edit | edit source]

The TTM by Prochaska and Di Clemente (1983) consist of five stages related to changing individuals behaviour. Pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation are the motivational stages of the theory where the idea of changing behaviour varies from not at all to ready to change . These stages are followed by action and maintenance, during these stages the behaviour has been modified for less than six months and then established over the next six months. Depending on how the individual reacts to the process of change progression and regression between stages can occur. There are ten processes of change that need to be considered when changing behaviour and each can relate to specific stage in the model (Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente & Fava, 1988). These are the actions taken by the individual to develop a rationale for their changing behaviour it will help them overcome any potential barrier they may encounter in their pathway through the stages of change.

Table1. Transtheoretical model constructs (Glanz et al. 2008)

Table1. Transtheoretical model constructs (Glanz et al. 2008)

Prochaska et al. (1992) proposed that the effectiveness of the process of change will vary according to the individual's stage of readiness to change. From a physiotherapy perspective the processes of change could affect an individual’s behaviour towards an intervention in numerous ways. For example, consciousness raising will make the patient more aware of why they are performing the intervention, Self-liberation will provide the individual with the belief that committing or recommitting to an intervention will lead to behavioural change and to act on that belief (Glanz et al. 2008) and helping relationships such as the relationship between physio and patient will also help to facilitate change. These are just three of the ten processes of change and each process may have an impact on different stages of change. The aforementioned will affect the pre-contemplation, contemplation and action stages of the TTM.

Figure 4. The Transtheoretical model taken from Adams and White (2003)

Figure 4. The Transtheoretical model taken from Adams and White (2003)

Furthermore within the TTM there are different measures of behaviour that affect the individual's progression through the stages (Velicer et al. 1998). These measures include decisional balance , self-efficacy and temptation. The decisional balance aspect of the theory involves weighing up the pros and cons of changing. The use of self-efficacy within this model was adapted from Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (1982). It is defined as the confidence the individual has in their ability to cope with situations where a relapse is extremely likely. Temptation is the intensity of urges to engage in a specific behaviour when the individual is in a certain situation (Glanz et al. 2008). These concepts can be analysed by a temptation measure or a self-efficacy measure as both are similar in structure (Velicer, DiClemente, Rossi & Prochaska, 1990). These outcome measures are particularly useful in that latter stages of change and beneficial establishing why a relapse has occurred (Velicer et al. 1998). If we examine the model as a whole, the stages of change are the central construct of the TTM, the processes of change are theorised as independent variables, and decisional balance, self-efficacy and temptations are hypothesized as intermediate dependent outcomes (Velicer et al. 1998; DiClemente, 2003).

The TTM has been used with varying degrees of success across a wide range of interventions such as smoking cessation, diet, stress management, medication adherence, alcohol abuse and physical activity and has been used in a variety of settings including the home, community and workplace. In a review by Adams and White (2003) the researchers examined TTM interventions and physical activity adherence and found that within the literature, due to the nature of voluntary participants in the interventions the subjects who completed all follow up measurements were predominantly white, middle class, female, and regularly active despite having a more diverse population initially (Cardinal and Sachs 1994; Marcus et al. 1998; Paterson and Aldana 1999 Norris et al. 2000; Boch et al. 2001). This can undermine the reliability and validity of the results as it doesn’t take into account the persons from a lower socioeconomic groups and participants at the precontemplation stage who are the most likely to benefit from this type of intervention. For the TTM to promote inclusion it is necessary that all studies represent participants at all stages of activity not just those who are initially sedentary or already active (Adams and White, 2003). One of the other key findings from this review was that the interventions were more successful in promoting physical activity in the short term this was due to a limited number of studies measuring the effect of their intervention in the long term.

Existing literature has proposed that stage-based interventions such as the TTM are more successful than non-stage based interventions (Prochaska, DiClemente, Velicer & Rossi, 1993; Campbell et al., 1994). This has been scrutinised by more current literature concerning the effectiveness of this approach in changing health-related behavior (Bunton, Baldwin, Flynn & Whitelaw, 2000; Littell & Girvin, 2002). Therefore it is necessary to examine some of the reasons why the TTM may lack value.

The TTM was originally developed for addictive behaviours. A lack of evidence may be due to some behaviours being more suited to the TTM than others. This has been mentioned previously by Orford (1992) in relation to the TTM being more suitable to smoking interventions than to alcohol or drug use. Povey et al. 1999 also came to the conclusion that it is difficult to use with dietary interventions. Other authors have proposed that in order to accurately analyse the effectiveness of the TTM, behaviour change should not be the only focus of an intervention and the researcher should aim to influence alternative outcomes such as increases in knowledge in order to progress through the stages of change (Campbell et al., 1994; Cole, et al. 1998). Although this contradicts itself as the end result of stage progression is ultimately behavioural change (Clarke & Eves, 1997). Bridle et al. (2005) stated that a theory-driven interventions of behavioural change should take into account several essential features. There must be identification of an individual’s readiness to change. Once this has been established the intervention can be suited to that initial stage and all theoretical variables that the TTM hypotheses in order to enable stage progression. Following this the stage of change and other variables need to be continually assessed, and the intervention should be adaptive to the individual's readiness to change. This process should be replicated until a change in behaviour has taken place. Following the pathway will result in tailored interventions that react to individual’s progress through the different stages of change in the TTM (Bridle et al. 2005).

The TTM has been used in a telehealth setting previously via a mobile phone interventions. Obermayer et al. (2004) and Riley et al. (2008) who used text messaging (sms) interventions to promote smoking cessation and found 25% difference in participants who managed to quit smoking after six weeks using the same intervention and a similar patient age group. Therefore using the TTM could be beneficial for specific patient groups within a physiotherapy setting as long as the intervention develops as the patient progress through the stages of the model in order to develop the desired behavioural change.

The TTM and ICF framework The ICF framework takes into account all the biopsychosocial factors necessary for regaining health and is well established within physiotherapy practice. The use of behaviour change models, in particular the TTM, can coincide and relate to the ICF framework and as suggested by Riley et al. (2008) should be adapted to meet the needs of the individual over time. When a physiotherapist is implementing an intervention for a specific patient, the goals will be patient centred. Therefore the physiotherapist must understand what the needs of the patient and investigate these needs further and establish the barriers and facilitators which may present themselves during the intervention (Homa and Patterson, 2005). Once the appropriate subjective and objective examinations have been implemented the correct application and choice of techniques is imperative and there must be an assessment of whether or not the intervention has been successful (Homa and Patterson, 2005). As the patient is moving through the stages of change the ICF model will be used at each stage to ensure patient centred practice. It is important that we, as the physiotherapist look at all the biopsychosocial considerations before developing our clinical reasoning for a behavioural change intervention (Jelsma and Scott, 2011).

Self-efficacy theory[edit | edit source]

Self- efficacy theory was first proposed by Bandura (1982) it refers to an individual's sense of confidence in their ability to execute a specific behaviour in different environments (Bandura, 1997). An individual’s level of self-efficacy will depend on the amount of perseverance and effort applied to a specific behaviour (Bandura, 1982). The individual's view of their efficacy may shape their actions, effort and attitude (Bandura, 1977; Eysenck, 1978). An essential component of self-efficacy theory is that the stronger the belief a person has in their ability to perform a set of actions, the more likely they are to comply and maintain participation throughout an intervention. However, those who have an inferior amount of self-efficacy could apply less effort and have an increased chance of relapsing when trying to change their behaviour (Bandura and Cervone, 1983). Furthermore Bandura (1997) suggest that a person's level of self- efficacy is based on personal beliefs rather than objective assessments. Therefore a person’s beliefs can often predict their behaviour more accurately than their capabilities. This can result in a behaviour level that does not match the individual's capabilities and could be why behaviour between individuals varies even when they have similar understanding and skills set (Lee et al. 2008). It could then be argued that having self-efficacy alone could be sufficient enough to initiate a behavioural change (Bandura, 1997).

There are many barriers to self-efficacy especially in the elderly and vulnerable populations that telehealth interventions are designed for. Misunderstanding the ageing process among older adults may result in restricted activity levels (Lachman et al. 1997). Lack of knowledge about the benefits of exercise may produce a dismissive attitude toward participation towards interventions involving physical activity (King et al. 1992). More so, Supposed ill health and symptoms related to physical disabilities associated with chronic disease are reasons behind dropping out of an intervention (Clark, 1999; Lian et al. 1999). Within this population group many of the barriers to activity are attitudinal and we must use the self-efficacy theory in order to provide appropriate interventions that install confidence and believe in the individual to help them to modify their behaviour. (Lee et al. 2008).

Existing literature has concluded that self-efficacy-based interventions to improve physical activity levels had a significant effect on outcome measures such as distance walked among older adults (Allison and Keller, 2004) and improvements in physical activity levels (Allen, 1996), but not in self-efficacy itself. This could indicate that self-efficacy is not necessary for bringing change in physical activity behaviour. This has been further emphasised by Calfas et al. (1997) and McAuley et al. (1994) who also used theory based interventions and found no connection between self-efficacy and behavioural change. Another limitation with self-efficacy literature especially with physical activity interventions is the lack of reporting by the authors on the actual content of the intervention making it difficult to compare interventions and standardisation of behavioural change techniques (Ashford et al. 2010).

Conversely, physical activity interventions aiming to improve self -efficacy have improved confidence and the individual's adherence to physical activity interventions (Dunn et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2007). Existing research confirms that self-efficacy beliefs are critical in the initial adoption of an exercise routine (Lee et al. 2008). If the participant is able to believe that they can exercise under circumstances that could result in the relapsing behaviour it is more likely that they will take part in exercise intervention (Clark, 1996; Sallis et al. 1988). Therefore including self-efficacy theory in the design of physical activity intervention would be advantageous in guiding the participant towards adopting a new behaviour. Furthermore, In a systematic review by (Ashford et al. 2010) they found that self-efficacy was increased when the parts of the intervention was performed by a peer prior to the participant taking part and therefore knowing that another person was able to perform the activity gave the participants increased confidence in their own capabilities.

In summary self -efficacy is a vital component of behavioural change, confidence in one’s ability to perform a certain behavioural change intervention. Looking at self-efficacy from a physiotherapy perspective it would apply the same principles as the physical activity interventions mentioned above. Influencing beliefs and establishing barriers to interventions could be influential when developing a telehealth intervention. Self-efficacy could be essential in patients complying with any intervention that may be beneficial to their health including mobile applications aimed at a specific injury, a health condition or chronic pain intervention.

Motivation[edit | edit source]

Motivation is complex term, and has been subjected to various definitions and approaches. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) defines motivation as “a phenomenal experience being a sufficient reason for action”, which then lead Deci and Ryan (2000) to further develop its content focusing on the “functional significance of events” as the main determinant for motivation.

In Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985) separate motivation into types, centred on the different goals that lead to the development of an action:

1. Intrinsic motivation, which denotes the act of doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable thus leading a person to act for the fun or challenge rather than because of external prods, pressures, or rewards. Spontaneous behaviours, which confer benefits to the organism, are not completed for any instrumental reason rather than constructive experience associated with exercising and empowering one’s capacities.

2. Extrinsic motivation, which denotes the act doing something because it leads to a separable outcome: social demands and roles that require individuals to assume responsibility for non-intrinsically stimulating duties. It can be further defined into four categories:

• External regulation, in which individuals perform tasks to satisfy an externally imposed demand.

• Introjection, in which individuals perform tasks in order to avoid guilt or anxiety or to enhance self-esteem.

• Identification, in which individuals identify the own importance of a behaviour, accepting its rules as his or her own.

• Integration, in which individuals entirely assimilate rules and regulations and those are congruent with his or her own values and needs.

3. Amotivation, which refers to the state of lacking an intention to act. Individuals who are amotivated lack intentionality and sense of personal causation due to the fact that they are not valuing an activity, not feeling competent to do it, or not believing it will lead to a desired outcome.

Motivation between individuals varies in amount, level (how much?) and orientation (what type?). Orientation of motivation refers to the essential attitudes and goals that lead to the development of a certain action (why are we doing this?). Research across various settings supports the role of communication in enhancing psychological functioning, self-regulation and intrinsic motivation.

The ideal situation is that an individual is able to self-monitor himself because he truly believes in the intervention and knows how this is intrinsically important for him/her (Teixeira et al. 2012) or because enjoyment of the activity leads to the adoption of a certain lifestyle (Cocosila et al. 2009). If neither self-consciousness or enjoyment could lead an individual to change its behaviour towards a healthier lifestyle, family encouragement and family cohesion could determine better outcomes within the rehabilitation setting (Rosland et al. 2011)

Self-determination theory[edit | edit source]

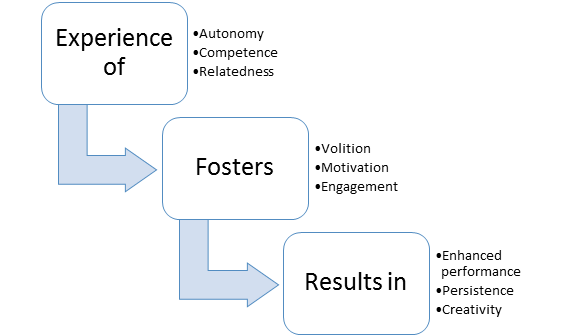

Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) is a macro‐theory of human motivation, personality development, and well‐being. The theory focuses especially on volitional or self‐determined behaviour and the social and cultural conditions that promote it. (Ryan et al. 2009)

Ryan and Deci (2000) propose three basic human needs involved in self-determination which motivate people to initiate behaviour:

1. Autonomy, which is the perception of experiencing a sense of choice and psychological freedom in the initiation of activities,

2. Competence, which is the ability to master challenges and the perception of being effective in dealing with the environment,

3. Relatedness, which is the sense of being cared for and connected to other people.

The quality of motivation is enhanced when any of these needs is satisfied, optimized if all three are satisfied and diminished if the person feels frustrated (Sanli et al., 2012).

A person’s motivation for an activity is a dynamic and constant continuum which development is based on certain aspects. External factors reduce feelings of autonomy thus prompting a shift from autonomous to controlled motivation or amotivation. On the other side, several other factors promote autonomous motivation (Visser et al. 2010).

Motivational states exist along this SDT continuum with amotivation (a state in which there is no intention to act) being the bottom form of motivation and intrinsic motivation (a state in which an action is performed for purely joy and interest of the activity itself) being the top form.

Extrinsically motivated behaviors, cover the continuum between amotivation and intrinsic motivation, varying in the extent to which their regulation is self-determined. These include external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation and integrated regulation. Externally regulated motivation (i.e., the least self-determined form of extrinsic motivation) results in behaviors performed to obtain rewards (e.g., praise, monetary compensation) or to avoid negative consequences (e.g., criticism from others).

Goal setting[edit | edit source]

The Aristotelic theory of final causality, in which every action is caused by a purpose, is the basic connection between Ryan and Deci (2000) SDT Theory and Locke (1996) Goal-Setting theory.

“A Goal is the object or the aim of an action” (Locke, 1996)

Goals have both internal (ideas) and external (object or condition to which they refer) aspects.

Goals help individuals to serve their dispositional desires, channelling them in a more concrete direction to be satisfied in an effective and efficient manner: internal aspect guides action to attain the external, desired state. (Ryan and Deci 2002).

Goals vary in content (the inner object) and intensity (the scope, focus of the selective process).

Locke et al. (1996) demonstrated the goals vary qualitatively (the goal content is what the person is seeking) and quantitatively (difficulty and specificity influence the content of a goal), summarizing that:

The more difficult the goal, the greater the achievement

The more specific or explicit the goal, the more precisely performance is regulated

Goals that are both specific and difficult lead to the highest performance and commitment.

Commitment to goals is attained when the individual is convinced that the goal is important and attainable.

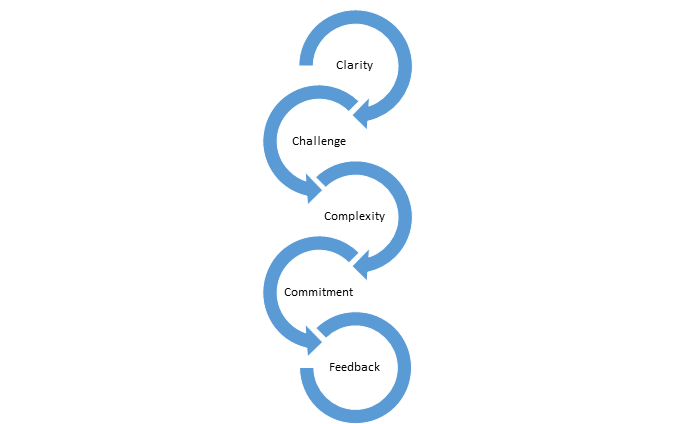

To underlie the importance of setting specific and difficult goals that, with feedback, lead to higher performance, Locke developed 5 fundamentals principles that constitutes an effective goal setting:

• Clarity: Goals are measurable and unambiguous. There should be no misunderstanding regarding which behaviours will be rewarded.

• Challenge: Goals are challenges. If a task is too easy, don’t expect the accomplishment to be significant.

• Complexity: if Goals are highly complicated, make sure that the individual won’t fight in the face of overwhelming odds.

• Commitment: Goals acceptance implies effort, over time, towards the accomplishment.

• Feedback: provides knowledge on progress towards the Goals.

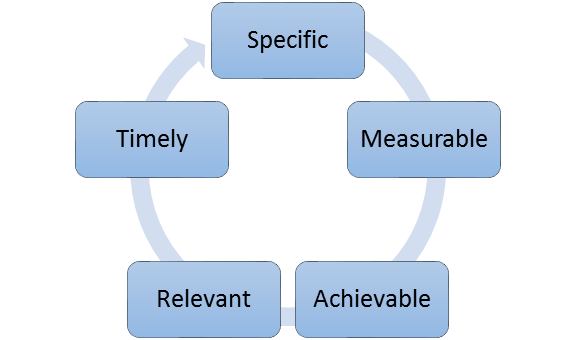

In 1981, Doran published an article titled “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives” in which described a new criteria on how to write meaningful objectives:

Despite the SMART acronym it clearly derives from Goal Setting Theory and is widely used in rehabilitation setting (Bovend'Eerdt et al., 2009). some limitations could arise:

•Specific, but changeable!

•Measured, by patient or by health carers or by both?

•Achievable, but may still be challenging!

•Relevant, to whom?

•Time, limited by who?

Clinical implications[edit | edit source]

Maclean et al. (2000) investigated the role of motivation in clinical settings, stating its importance in determining patient outcomes and underlying the difficulties encountered when promoting its development. To increase patient’s motivation, the authors suggest:

•Goal setting (clear and revisable), including patient feelings and point of views (which should be accepted and respected)

•Accept patient’s idiosyncrasies and worth patient’s value system

•Have a warm, approachable and competent manner

•Remind the patient that goals exist beyond the ward setting

•Do not stress the responsibility for motivation and recovery merely on the patient

Future research could focus on improving our telehealth behaviour interventions but also our theoretical and practical understanding of health behaviour change (Riley et al. 2008). However, from the research associated with specific models as a theoretical basis for other types of intervention there is generally an improvement in patient behaviour. In the development of applications is important that we can tailor the intervention to suit the individual and are able to SMART set goals, motivate and ensure progression through behaviour change models in the short term as well as in the long term.

Research[edit | edit source]

Current smartphone applications and modernization of physiotherapy

[edit | edit source]

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

Current physiotherapy applications[edit | edit source]

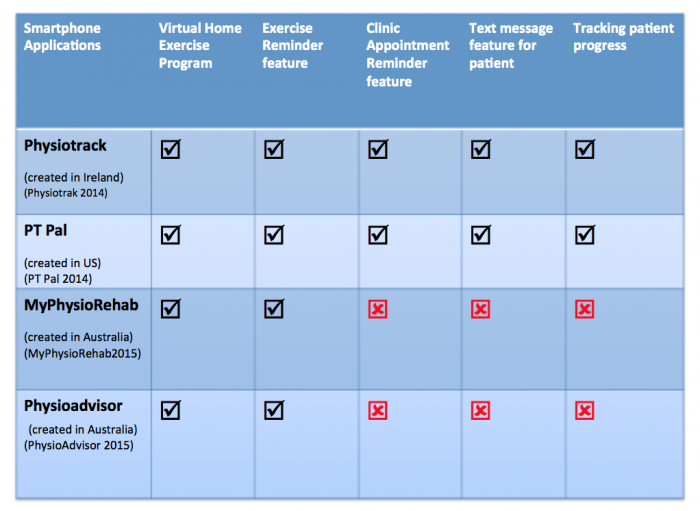

The following table compares key features of four different smartphone applications used worldwide in the creation and training of the home exercise programme (HEP) for the patient. Descriptions of their key HEP features, communication outlets, tracking/ reports and costs are outlined below.

PT Pal (PT Pal 2015)

PT Pal is a HIPPA compliant smartphone application launched in 2013 that was designed as a patient-centered approach to increase patient compliance with home exercise programs. Naveen Khan, a patient who was having difficulty adhering to her own physiotherapy program, is the founder and CEO of PT Pal. The application includes an exercise database for allied health professionals including Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists and Speech and Language Therapy. This application is constantly expanding and caters to multiple patient groups such as adult, paediatric, cognitive, specific care such as hip and knee as well traumatic brain injury. For the purpose of this wiki we will be discussing the app’s use for general musculoskeletal injuries for adults in physiotherapy practice.

PT Pal is an application that aims to solve patient non-compliance by storing, tracking and scheduling a patient's physical therapy exercises.

Further considerations: Improved communication [edit | edit source]

Facilitating patient-provider relationship[edit | edit source]

Utilising reminder services to enhance communication[edit | edit source]

Facilitating Knowledge and Education through Physiotherapist communication[edit | edit source]

Communicating the right exercise prescription[edit | edit source]

Further considerations: Facilitating behaviour change[edit | edit source]

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation towards rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Self-efficacy and goal setting[edit | edit source]

Cost effectiveness[edit | edit source]

Limitations

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the limitations

Conclusing Remarks [edit | edit source]

add text here relating to key evidence with regards to any of the above headings

CPD Test your knowledge [edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.