Tackling Physical Inactivity: A Resource for Raising Awareness in Physiotherapists

Original Editors - Jason Chang, Andrea Christoforou, Maria Cuddihy, Christine Gorsek, Annika Höbler as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

INTRODUCTION TO RESOURCE[edit | edit source]

NB: Currently under HEAVYconstruction. Please stand by. Thank you. (November 2013)

PHYSICAL INACTIVITY: 'THE BIGGEST PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM'[edit | edit source]

Physical inactivity has been deemed "the biggest public health problem of the 21st century"[1] and has been shown to kill more people than smoking, diabetes and obesity combined (Figure 1)[2]. It is ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, killing approximately 3.2 million people (~6% of the total deaths) annually and accounting for approximately 32.1 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs; ~2.1% of global DALYs) annually[3].

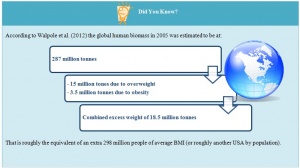

The major burden of disease attributed to physical inactivity is a result of its established role as one of the main risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer. In 2008, NCDs were responsible for 63% of the 57 million deaths worldwide[4] , with physical inactivity estimated to be directly responsible for 6% of the disease burden from coronary heart disease, 7% of type 2 diabetes and 10% of each of breast and colon cancers[5]. If physical inactivity were eliminated, this would translate to an estimated 5.3 million lives being saved each year, or - more realistically - 533,000 or 1.3 million lives saved if physical inactivity were reduced by 10% or 25%, respectively[5]. This is independent of the increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to other factors, such as adiposity, raised blood glucose concentrations and high blood pressure, which are directly influenced by physical inactivity[6]. In particular, obesity engages in a 'vicious cycle' with physical inactivity amplifying the burden to public health (ref Pietiläinen et al) (see Did You Know?).

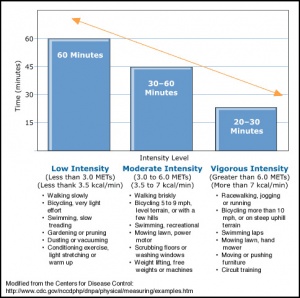

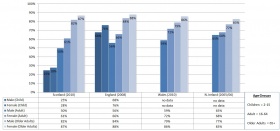

A recent analysis of global data collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 31.1% of adults (aged 15 years or older) worldwide are physically inactive[7]. For this analysis, physical inactivity was defined as not achieving the equivalent of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity at least 5 days per week or 20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity at least 3 days per week[7]. Inactivity was found to increase with age and socio-economic status[7]. For adolescents aged 13 to 15 years old, the problem appears to be worse, with more than 80% reportedly not achieving the public health goal of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day, and with girls being less active than boys[7]. Figure 2 summarises the levels of inactivity, defined as not meeting the recommended national physical activity guidelines for the year listed, in the four UK nations (ref BHF 2012), mimicking the global trends with respect to age and gender (ref: HallalGlobal). The relationship between socio-economic status and physical inactivity, however, is reversed in the UK, with individuals in the lowest income bracket exhibiting higher levels of inactivity than those in the highest income bracket (ref BHF 2012).

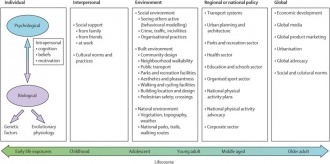

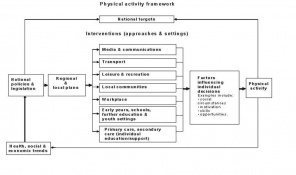

The factors contributing to the 'pandemic of physical inactivity' (ref Kohl 2012) extend beyond the individual. Increasingly, it is being recognised that social, cultural, environmental and national and global policy level factors also play a substantial role, as represented by the proposed ecological model of physical activity (Figure 3) (ref Bauman et al 2012). Effective management of physical activity thus requires interventions targeted at all levels[8]. Accordingly, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have developed a comprehensive, multi-level Physical Activity Framework at which to target interventions (Figure 4) (ref PH8 http://publications.nice.org.uk/physical-activity-and-the-environment-ph8/public-health-need-and-practice#physical-activity-framework).

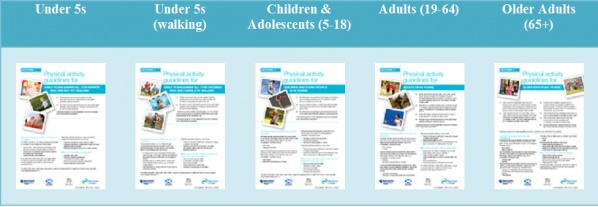

To that end, physical activity initiatives have propped up around the world. Leading the global forum, WHO have adopted the WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health, publishing recommended physical activity guidelines and providing implementation aids to support national policymakers[8]. In the UK, Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries' Chief Medical Officers was recently published (in 2011), providing updated national guidelines, the evidence underpinning them and guidance for their local implementation[9]. Links to other examples of global and national initiatives are provided below. Physical activity is finally being recognised as a public health priority.

Further Reading[edit | edit source]

CPD[edit | edit source]

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY: THE 'BEST MEDICINE'[edit | edit source]

All parts of the body which have a function if used in moderation and exercised in labour in which each is accustomed, become thereby healthy, well developed and age more slowly; but if unused and left idle they become liable to disease, defective in growth and age quickly.

- Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, ca 400 B.C.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

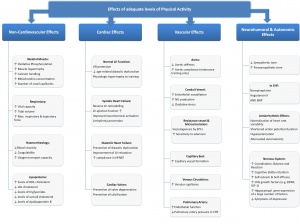

In addition to the high prevalence of and risks associated with physical inactivity, physical activity has become a public health priority[8] because of the overwhelming body of evidence supporting its effectiveness as a holistic health intervention (ref Warburton: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/174/6/801.full.pdf+html). While physical activity has only recently (circa 2000) factored into the public health agenda[8], quantitative evidence of its widespread health benefits has been formally emerging since 1950s. In the 1950s, Professor Morris and colleagues showed that men engaged in work requiring a level of physical activity (e.g. active conductors or postmen) were less likely to suffer from coronary heart disease than men with sedentary jobs (e.g. bus drivers or clerical workers)[10]. Sixty years later, the evidence continues to materialise, with a recent study suggesting that exercise can be as effective as pharmaceutical interventions in the prevention and rehabilitation of a number of health conditions, particularly stroke[11].

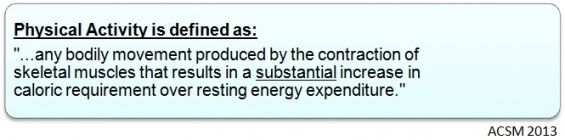

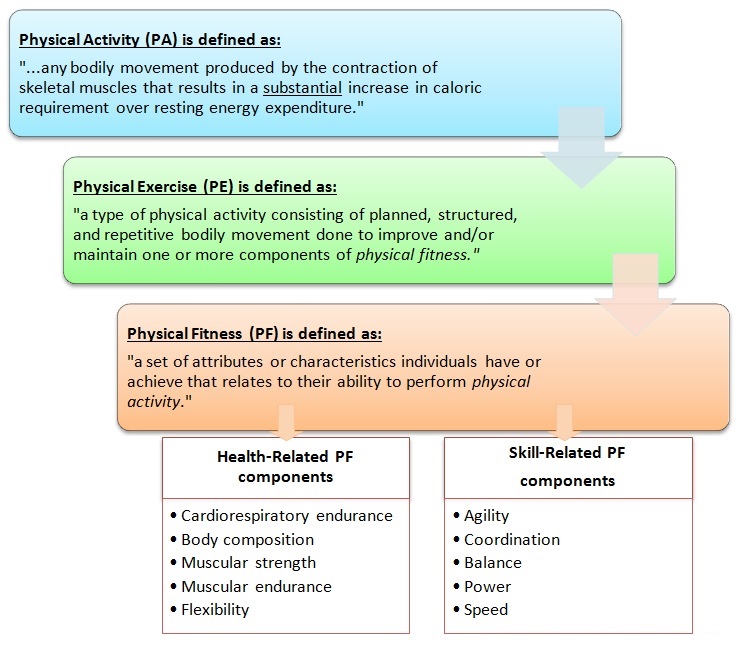

Physical activity refers to “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle that uses energy” (ref: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/physical_activity/facts/en/index2.html) and can involve anything from daily household chores to structured exercise and sport. (It is important to note, however, that the terms 'physical activity' and 'exercise' are often used interchangeably (Blair LaMonte Evol of guidelines).) The general benefits afforded by physical activity are not restricted to physical aspects of health (e.g. reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (Schuler, Adams and Goto 2013)), nor are they restricted to any particular age-group or clinical population. Substantial evidence supports positive effects on cognition, mental health and well-being (Cotman et al 2007; Lange-Asschenfeldt and Kojda 2008; http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11916-007-0004-z). Futhermore, these physical and mental health benefits traverse the lifespan - from the very young to the very old (Hillman et al 2008; http://www.cmaj.ca/content/174/6/801.full.pdf+html; Hyde, Maher, Elavsky: Enhancing our understanding of phys activity…). They also apply to various ‘clinical’ as well as non-clinical populations, including, for example, individuals living with chronic or long-term conditions, such as low back pain (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19217208), multiple sclerosis (http://msj.sagepub.com/content/14/1/35.abstract) or cystic fibrosis (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095254612000804) and the ‘generally well’ population (http://www.cmaj.ca/content/174/6/801.full.pdf+html).

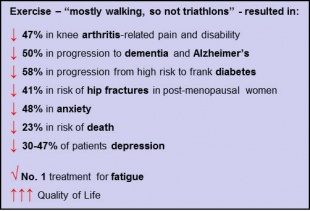

The YouTube video by Dr. Mike Evans below provides a stimulating and compelling overview of the evidence, with some key points highlighted in the box to the right:

|

23 and 1/2 Hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health? |

Key Points: |

Sedentary Behaviour[edit | edit source]

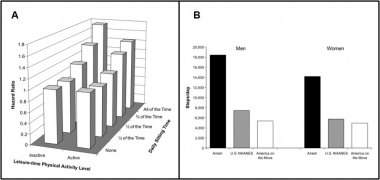

As emphasised in the video 23 and ½ Hours and embraced by the latest physical activity guidelines <hyperlink to next section?>, the ‘dose’ of physical activity that seems to confer the majority of these health benefits (in adults) is 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity on most days of the week (ref Blair, Lamonte, Nichaman 2004: evolution of PA guidelines). However, one aspect of physical activity promotion that this dose recommendation does not address is sedentary behaviour. Sedentary behaviour refers to the execution of activities involving sitting or lying that result in low levels of energy expenditure, such as sitting during a commute, at a desk at work or in front of the TV at home (Bussman et al: To total the amount of activity..2013). An overwhelming body of evidence is mounting to suggest that sedentary behaviour is associated with increased risk of chronic disease and death and has its own pathophysiological profile, independent of the execution of moderate to vigorous physical activity (Figure 5) (Wilmot et al 2012; Owen et al http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3404815/?tool=pubmed; Bankoski: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/34/2/497.short). Fortunately, given the amount of time potentially spent sitting each day (see Did You Know? below), there is also evidence to suggest that short breaks in sedentary time can confer substantial health benefits (http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/31/4/661.short; http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/5/590.short), as highlighted in the short video below.

|

Is Sitting On Your Backside Dangerous? |

|

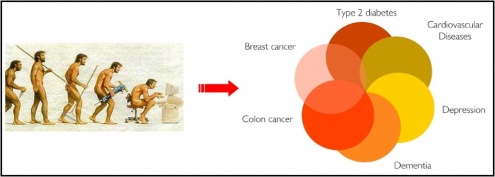

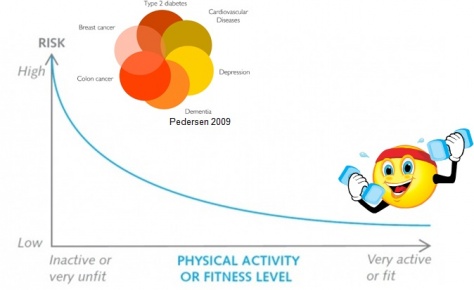

The cumulative evidence of the risks and benefits of physical inactivity and activity, respectively, should not be surprising. Humans are built for movement. As hunters and gatherers for most of human history, our genes have evolved to accommodate the high energy expenditure levels required to be ‘the fittest’ and survive in those prehistoric conditions (Katzmarxkk: paradigm shift paper; Booth review 2002…). Yet, since the industrial revolution and development of modern conveniences, modern-day humans have become less active overall (Figure 6) (ref Katzmarzyk), thus disrupting that inherent homeostatic mechanism (Booth 2002) and leading to the manifestation of 'the diseasome of physicial inactivity' (ref Pedersen 2009) (Figure 7) (Pedersen 2009; Figure in http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805368/).

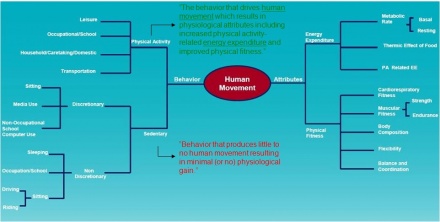

Thus, it is clear that the physical activity paradigm should incorporate sedentary behaviour (Katzmaky), and physical activity initiatives and recommendations should adapt accordingly (ref: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12170-008-0054-8#page-1; ref: time to stand up for your health diabetelogica 2011;). To further aid in this endeavour, a new conceptual framework has evolved, redefining physical activity and representing the complex, multi-dimensional nature of physical activity and sedentary behaviour as components of human movement (Figure 8) (ref http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22287443).

The Development and Evolution of Physical Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Beginning with Morris’ work on occupational physical activity in the 1950s (ref Paffenbarger, Blair and Lee), the evidence emerging from the years of epidemiological research of the risks associated with inactivity or a sedentary lifestyle provided the rationale for the development of physical activity guidelines (Blair, LaMonte 2004). Identifying the appropriate ‘dose’ of physical activity that would extract the greatest reward in public health, however, required an ongoing examination of data emerging from both epidemiological and exercise training studies and the decision to focus these recommendations on the population who would benefit most, namely those who were most inactive and thus contributing most to the public health burden (ref Lee&Skerret 2001; ref Blair, LaMonte 2004).

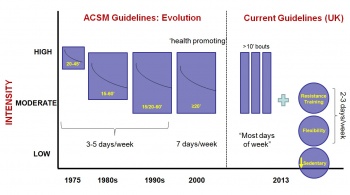

Figure 9 below summarises the evolution of the physical activity guidelines. The first, which came out in the 1970s, called for continuous, high-intensity physical activity, with the goal of achieving physical fitness rather than promoting health (ref Blair La Monte). Subsequent studies, which revealed substantial health benefits from lower levels of intensity (ref Blair La Monte) and the identification of a clear dose-response relationship between the amount of physical activity and the health benefits (ref Lee and Skerret) allowed for flexibility in the achievement of the guidelines. It had become clear that the main contributor to health was not so much the intensity but the volume of physical activity executed, with those performing enough to expend on the order of 1000kcals per week reaping the majority of the health benefits (ref Lee and Skerret).

More recently, additional evidence of the complimentary effects of resistance training, of the enhancing effects of flexibility training (http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/101/7/828.full), of the sufficiency of meeting the guidelines with as little as 10-minute bouts of physical activity (Loprinzi 2013) and the clear physical-activity-independent risks associated with sedentary behaviour (Figure 5 (ref Katzm)) has informed the current physical activity guidelines (Figure 9) provided by WHO and various nations worldwide. Table 1 compares the guidelines provided by WHO and the UK. Links to WHO's and various nations' physical activity guidelines are provided below.

WHO Guidelines[4]

US Guidelines[5]

UK Guidelines[6]

Irish Guidelines[7]

Canadian Guidelines[8]

Australian Guidelines[9]

New Zealand Guidelines[10]

PHYSIOTHERAPISTS AS 'PHYSICAL ACTIVITY CHAMPIONS'

[edit | edit source]

First, do no harm...

- Hippocratic Oath

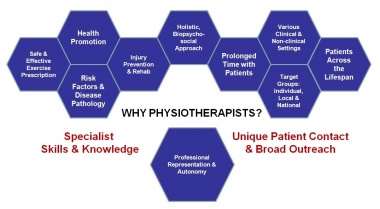

Physiotherapists have the potential to make a substantial impact on individual, community and public health. Their holistic, biopsychosocial (newref: Sanders 2013), and non-invasive approach, professional autonomy (newref: HCPC standards), specialist knowledge and skill set (newref WCPT policy statement at http://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-exercise%20experts), relatively prolonged patient contact time and varied clinical practice populations and settings places the physiotherapist in the ideal position for the widespread promotion of physical activity (refs: Khan guest editorial: http://sunshinephysio.com/resources/articles/PhysicalActivityChampions.pdf) Dean 2009 and WCPT ppt on ActivityandHealth).

In the past, physiotherapy intervention, including exercise prescription, has predominantly focused on the restoration of function lost as a result of an acute incident or on the maintenance of function in neurological or cardio-respiratory disease (ref Verhagen and Engbers 2008 role of physio). However, a shift in the public health need toward the prevention or management of chronic lifestyle conditions, including NCDs, obesity, osteoarthritis and depression (WHO ref 4), and toward the mitigation of the effects of ageing an increasing ageing population (newref: Spijker 2013) has demanded a shift in the role of the physiotherapist in addressing this need through the widespread promotion of physical activity (and other health-promoting lifestyle changes) (ref Dean pt1). Recognising this emerging role and “professional and ethical responsibility” (ref Dean-ptI), physiotherapy professional bodies around the world have brought physical activity promotion to the forefront of their agenda with links to two clear examples provided below:

Notably, in Scotland, in association with the Allied Health Professionals (AHP) National Delivery Plan (2012-2015), which includes physiotherapists, the AHP Directors Group have formed the Physical Activity and Health Alliance (PAHA) and have pledged to “…work with a range of partners to increase the level of physical activity in Scotland” (newref: http://www.paha.org.uk/Announcement/ahp-directors-physical-activity-pledge).

Since physical activity participation is influenced by multiple factors, including individual, socio-cultural, environmental and government policy (Figures 3 and 4), there is potential for physiotherapists to intervene at all levels. The remainder of this resource offers guidance on how this may be achieved.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY FOR THE INDIVIDUAL[edit | edit source]

Physical activity promotion at the level of the individual is not a novel concept. As first-point-of-contact practitioners, primary care providers, particularly GPs, have acknowledged a necessary role in physical activity promotion for decades, with varying degrees of follow-through in different countries (Weiler & Stamatakis 2010). Serving as role models, Sweden have been providing “Exercise on Prescription” since the 1980s (Hellenius & Sundberg), while New Zealand

have participated with the provision of the "Green Prescription” for the past 15 years (ref http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/prescription-good-health-green-prescriptions-action). Most recently, Scotland have joined in and launched a new physical activity pathway, in accordance with the AHP Director Group’s pledge (ref pledge) to “[a]gree a form of questioning and brief intervention for each patient, every time and embed this in all AHP services” (ref pledge).

In general, the past few years have seen a revitalisation in the push for physical activity promotion in primary (ref:Kahn 2011-exercise in primary care) and secondary (newref:Allison et al 2013) care. As multi-tier healthcare providers, physiotherapists can assume an active role by taking advantage of each patient encounter to assess and promote physical activity (O’Donahue&Dean 2010; Dean 2009, pt1). Three main features of physical activity promotion at the level of the individual are described below.

<text/picture with hyperlink to different sections?>

The Physical Activity 'Vital Sign'[edit | edit source]

Assessment is an important tool in the physiotherapists arsenal, enabling the collection of relevant information for a clinically-reasoned, holistic and patient-centred approach to diagnosis and subsequent management. Despite the evidence, patients’ habitual physical activity and sedentary levels are generally not assessed as part of the standard physiotherapy assessment[14][14].Yet, all patients coming into contact with a physiotherapist suffer from and/or are susceptible to the effects of physical inactivity, regardless of their presenting complaint. Thus, the assessment of physical activity and sedentary levels has a relevant place in the physiotherapy examination[15][15].

In the general medicine community, physical activity has been declared the fifth vital sign[16][16] – a modifiable sign that should be assessed at every clinical encounter[16][16][17][17]. Different approaches may be used to measure levels of physical activity (e.g. observation, heart rate monitors, motion sensors), but questionnaires are likely to be the most appropriate in the context of a typical physiotherapy assessment, given time and resource constraints[15][15]. Three alternatives for the assessment of a patient’s physical activity levels are describes below.

The General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ)[edit | edit source]

The GPPAQ was developed by the UK’s Department of Health in collaboration with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. It is a brief, validated screening tool for the assessment of adults’ (16 to 74 years) physical activity levels as they relate to their occupation and leisure time. It takes only 30 seconds to complete and additional few minutes to calculate the individual’s Physical Activity Index (PAI) and determine the level of intervention required (newref: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51962/).

| Download the Questionnaire! |

The Scottish Physical Activity Screening Question (Scot-PASQ)[edit | edit source]

The Scot-PASQ was developed and validated by NHS Health Scotland in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh (newref: http://www.paha.org.uk/Resource/scottish-physical-activity-screening-question-scot-pasq). It has been implemented in Scotland’s new Physical Activity Pathway. It is a brief screening tool that consists of three questions, the first two of which specifically assess whether the patient is meeting the minimum national recommendations.

| Download the Questionnaire! |

[edit | edit source]

The Kaiser Permanente Approach: The ‘Exercise Vital Sign’[edit | edit source]

Kaiser Permanente are a not-for-profit, California-based integrated managed care consortium that have adopted a simple method for assessing physical activity levels in each patient, at every visit (ref Sallis 2011). Coined the ‘Exercise Vital Sign” (EVS), it is brief screening tool that consists of two questions and has shown good face and discriminant validity (newref: Coleman http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22688832). It is described in the 40-second video below.

|

Kaiser Permanente: Making Exercise a Vital Sign |

Key Points: The EVS: "2 questions, 1 minute" (ref Sallis 2011) 1) “On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate or greater physical activity?” 2) “On those days, how many minutes do you engage in activity at this level?” |

Whether these or other assessment methods are applied, care should be taken that they are relevant to the patient’s age and clinical status to ensure accuracy in measurement[15]. It also should be borne in mind that one of the main limitations of using questionnaires to assess the overall physical activity levels of an individual is recall bias [15](ref Hussey&Wilson 2003). Most individuals (48-63%) tend to over-estimate their physical activity levels (Sjuijs 2007). It has also been observed with adolescents reporting their own physical activity levels (Corder 2011) and with mothers reporting the activity levels of their young children (Hasketh 2013). The Physical Activity Resource Center for Public Health (PARC-PH) at the University of Pittsburgh have developed an excellent resource, containing up-to-date information on various physical activity and sedentary behaviour assessment tools, the link to which can be accessed via the University of Pittsburgh's logo.

Physical Activity Resource Center for Public Health[17]

Finally, to enable follow-up and to adhere to the relevant professional record-keeping requirements (e.g. [19][23]), the results of the assessment should be documented in the patient’s medical records[17][17]. Appropriate management can then be implemented[16][16]. While it is debateable whether querying a patient’s activity level challenges their behaviour and perspective, it serves as a starting point and provides the opportunity to - at the very least - inform the patient of the potential consequences of his/her behaviour[16].

CPD – Suggest ‘Raising the Issue of Physical Activity’[20].

Mobilising Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is a complex, multifactorial (Figure 3) and multi-dimensional (Figure 7) health behaviour[21][22]. The role of the physiotherapist in counselling a patient to adopt, change or maintain such a behaviour can be equally complex. It may involve forming a partnership with the patient[23], defining the target behaviour (e.g. increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behaviour), exploring and addressing the unique combination of personal, socio-cultural, environmental, policy factors underlying the patient’s behaviour[21] [24] and identifying the most suitable (patient-centred) approach(es) to mobilise and help the patient sustain the behaviour[25]. Long-term adherence to physical activity is essential for the health benefits to be realised[26].

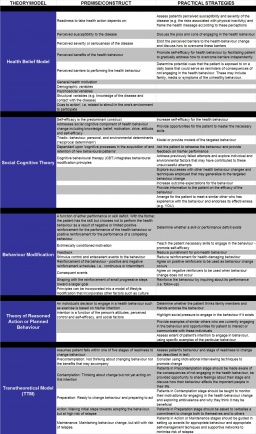

Several theoretical models of and counselling approaches for health behaviour change have been developed[27][28]. A working knowledge of these models and the various approaches to their practical application is another essential tool in the physiotherapist’s arsenal, if s/he is to help effect and sustain behaviour change in the patient. A summary is provided below.

Theoretical Models of Health Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

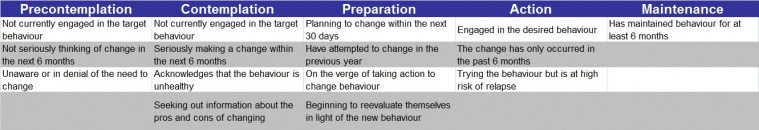

Table 2 provides a brief description of and practical suggestions for some of the most prominent theoretical models (ref Dean 2009 and Elder 1999). Among these, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)[29] has received the most attention in the field due to its ease and utility in clinical practice[27][30]. It assumes that a patient’s readiness to change falls within one of five stages, based on his/her level of engagement with the particular health behaviour[29] (Tables 2 and 3):

| Table 2. adapted from Dearn 2009 p2 and elder 1999 |

| Table 3. Adapted from Dean pt 2 2009 |

Determining the patient’s stage of readiness through a series of specific questions facilitates the identification of strategies or subsequent interventions that will be most effective in guiding the patient to progress to the next stage [28][30]. The Health Behavior Change Research (HBCR) workgroup at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa provide a series of relevant questionnaires for applying the TTM to physical activity. The American Council on Exercise® (ACE) offers practical guidance on how to use the TTM to help a patient make healthy behaviour changes. In particular, Motivational Interviewing, described below, has gained wide acceptance as an effective means of motivating behaviour change within the TTM framework[31].

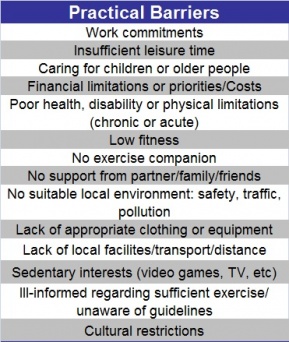

While the TTM and other health behaviour models suffer from limitations[30], they are useful in helping to understand the potentially modifiable factors that underlie behaviour and behaviour change. Taken together, these theoretical models converge on key, interrelated determinants of behaviour change[28][32]. In particular, self-efficacy (i.e. one’s perceived ability to execute the behaviour) [33][34][30][35], barrier identification and negotiation[36][24] (Table 4), S.M.A.R.T, patient-centred goal-setting[37][38] and feedback, including reinforcement and follow-up[27][24][39] have been found to significantly impact physical activity behaviour change. A physiotherapist can work with the patient to modulate these factors to promote behaviour change[27][32], using various approaches[40], some of which are described below.

|

Table 4. Various barriers reported by patients with respect to physical activity. (Compiled from references...) |

[edit | edit source]

Methods to Promote Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Behavioural counselling encompasses a spectrum of interventions, which can be rooted in one or more behavioural theories[25]. Two approaches - Brief Advice and Brief Intervention - do not require extensive training to be effectively executed (ref CSP – Brief Interventions: Evidence Briefing (physical activity…) and are integrated as part of Scotland's new Physical Activity Pathway[41]. A third approach, Motivational Interviewing, is also recommended, although it requires additional training [42].

Brief Advice [edit | edit source]

Brief Advice consists of a short (~3 minute), structured conversation with the patient aimed at raising awareness of the benefits of physical activity, exploring barriers and identifying some solutions. It may be suitable for a patient in the early stages of readiness, namely precontemplation and contemplation[28], or for a patient in the maintenance stage, requiring only reinforcement to maintain the behaviour[25].

Brief Intervention[edit | edit source]

Brief Interventions are longer (~3-20 minutes) structured conversations, which delve deeper into the patient’s needs, preferences and circumstances with the aim of motivating and supporting the patient toward the behaviour change in a non-judgmental and positive manner. More time is spent discussing the benefits of the behaviour change, addressing barriers, setting goals and building confidence.

The NHS Scotland Knowledge Network have produced short videos describing these two approaches as part of their Every Step Counts Learning pack, in which they describe the new Physical Activity Pathway.

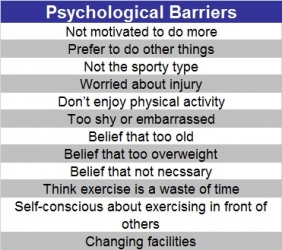

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational Interviewing (Rollnick and Miller 1995 – see refs in doc below) is a behaviour change intervention that has been most recently (2009) defined as “…a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change” (Rollnick&Miller2009). This short interview with William R Miller, the founder of Motivational Interviewing, describes the approach’s beginnings:

<insert video http://www.motivationalinterview.org/quick_links/about_mi.html>

Motivational Interviewing consists of two phases, the first in which intrinsic motivation is reinforced and the second in which commitment to change is enhanced[43]. It is based on five general principles (Miller 1983) (Table 5). Monash University in Australia have developed a learning resource, which includes videos in which the five general principles are modelled.

<hyperlink Monash University logo: http://www.monash.edu.au/pharm/current/step-up/motivational-interviewing/>

| Table 5. Adapted from SHinitizky |

Motivational Interviewing is an approach which aims to challenge the patient in a supportive and self-reflective manner, working under the assumption that the patient knows what is best for him/herself. The clinician’s role is to collaborate with, guide and support the patient through his/her journey of behaviour change. Although distinct from the Transtheoretical Model[42], Motivational Interviewing is often used in conjunction with it, as it has been shown to facilitate progression through the stages[31]. In particular, it has been shown to be effective in those who are in the low stages of readiness to change[44] and in a range of health settings[43].

As MI requires standardised training for optimal delivery [43], it presents an excellent CPD opportunity for physiotherapists[17]. The following site serves as a useful starting point:

<hyperlink MI http://www.motivationalinterview.org/index.html>

Further Reading

CPD

PA on prescription temp header

[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity 'On Prescription'[edit | edit source]

Education[edit | edit source]

In the context of education physiotherapists are advantageously placed to advice about the associated risks and benefits of physical activity and physical inactivity respectively. This is currently taking place in forms such as patient counselling, information leaflets and mass media communications.

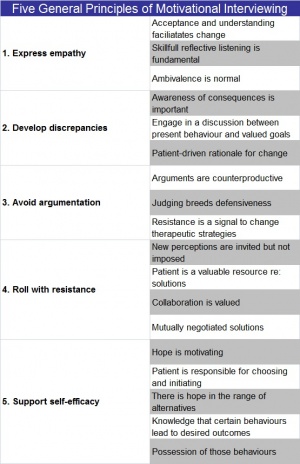

However, despite such concerted efforts Sluijs et al. (2007) found that much of the evidence points to a limited and moderate positive effect on influencing physical activity levels in the general population. In addition the lack of awareness regarding what it means to be physically active and the detriments of sedentary behaviour remains high.

Therefore, it is vital that we re-evaluate the way in which education in this topic is being delivered so as to maintain the credibility of new research in the eye of the public. The last thing the public needs is to be constantly bombarded with cautions and information coming from multiple sources with conflicting and/or inconsistent statements.

As physiotherapists we have a natural role in augmenting the practice of effective education through our advantage of having 1-to-1 patient contact time. Refining our delivery of education ensures we can ride the momentum of current studies and convey it to our patients, helping the public to be more self-sufficient in tackling this issue.

In a 2004 NHS briefing it was suggested that “behaviourally based interventions can be significantly more cost-effective than traditional service delivery” Interestingly, relating to the previous section on behaviour change it is a logical and tailored approach in tackling sedentary behaviour and eliciting greater physical activity. Combine effective education and the theoretical models of behavioural change there exists the potential to achieve:

- Increased knowledge and awareness of Physical Activity benefits & detriments of Physical Inactivity.

- Increased knowledge and awareness of services available – increasing self-efficacy and the potential of increasing adherence of new lifestyle.

- Changing attitudes and motivations.

- Changing beliefs and perceptions about Physical Activity, sedentary behaviour and social norms.

- Influencing how health services are used.

A positive outcome or consultation depends on our relationship with patients as physiotherapists. The topic of physical activity and sedentary behaviour can be a very sensitive subject as it relates to aspects of an individual’s way life which they may or may not wish to talk about or have even contemplated. Furthermore, we are essentially promoting a lifestyle change. Whether it be big or small, habits are never easy to change. Sluijs et al. (2007) mentioned two key issues to consider when it comes to a person’s intention to change:

- On the extent to which a person perceives their own behaviour as ‘unhealthy’.

- On the belief that a change in behaviour will decrease the health risks.

Thus, building on these two key principles of “intention to change” education can be tailored to obtain the greatest impact.

So…what then would the educational content be about?

This question would largely depend on the population group and the individual themselves. But a good place to start would be to revisit the definition of Physical Activity and to clarify the hierarchical structure to which physical Exercise belongs.

There is a common misconception that physical activity equals exercise and that exercise means having to go to the gym. This misrepresentation can easily become a contributing barrier.

It is our role as physiotherapists and ambassadors of health promotion to address any misconceptions early on to allow for any interventions and treatments to have any meaningful effect.

According to Sluijs et al. (2007) a study conducted in the Netherlands found that of those that were identified as physically inactive, 48%-61% of them overestimated their level of PA. This false perception of activity levels has also been shown in adolescent populations in the UK (Corder et al. 2011).

Risk and Benefits[edit | edit source]

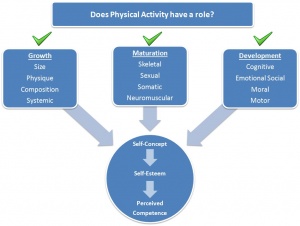

The prevailing and growing list of evidence concerning the physiological benefits derived from physical activity as seen in adults is also the case in children (Janssen 2010) and older adults (Haapanen-Niemi 2000). Although understandably the relative effects and magnitudes will differ somewhat between individuals and between ages. Thus, whilst we can universally educate all age groups concerning the biological benefits there are other motivations can be addressed by increasing physical activity.

Furthermore, physiotherapist has a profound role in health education. Patient contact may occur at any stage in a person’s life. Therefore when contemplating and discussing the benefits of physical activity it would be highly efficacious to also consider beyond the physiological underpinnings. For example consider discussing the benefits from engaging in physical activity by appealing to that individuals priorities e.g. self-esteem, socialising, making the school team, etc.

Children & Preadolescents

Education for individuals in this age group may benefit more if the advantages of physical activity were explained in concepts that would translate into motivations or an inspiration to achieving a goal not necessarily hinged on simply “being more physically fit”.

The early developmental years of children are vital in building a healthy foundation for their body to grow into. In fact the same benefits that apply to older adults, albeit with differing magnitudes, are true for children and preadolescents (ACSM 2013; SASA 2011). The more we move under different stresses the better our muscles, bones and other structures adapt. Similarly, physical activity is vital in improving the neurological development of the brain such as increased hippocampal volume and its related affects on relational memory tasks (Chaddock 2010).

It would be unjust to assume that children have no stress since the causes of such may be wholly subjective. We can address the psychosocial issues through physical activity which can target certain physiological changes that may contribute/result from stress, counterbalancing its effect.

Figure x. summarises the psychosocial issues relatively well in the context of the perception of oneself. PA can have an effect on all of the components of growth and development. Whilst some of the issues may be of lesser relevance concerning a toddler than a preadolescent it is important to instil the right sense of physical activity habit. Our body has naturally come to expect and need a certain amount of activity to thrive, we must therefore nurture it to prevent later-life issues.

Adolescent & Adults

Physical activity has both rehabilitative and preventative benefits regarding all aspects of health. Thus, it is important to also consider an individual’s mental health as much as is possible. Whilst we must not profess to be experts in this area we can nonetheless empathise in the best way possible. Take for instance the research by Baldwin & Hoffman (2002) where they have observed a drop in self-esteem in early adolescence. If coupled with poor body image or the social stigmas attached to overweight and obesity, mental health can suffer, possibly leading to a cycle of reduced social interactions and increased sedentary behaviour, and consequently a reduction in health. By maintaining a habit of physical activity it may help overcome some of these issues, and provide the individual the necessary toolkit in tackling and understanding these issues.

Furthermore, physical activity in early and later adulthood is important in gearing oneself for the natural and inevitable (avoid this word?) changes of aging. Physical activity has been observed as a factor in the development and maintenance of the brain (LE). Studies have shown moderate intensity cycling as having a positive effect on the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) whether it’s in healthy individuals or those suffering from chronic conditions such as multiple sclerosis (Gold et al. 2003). This can have implications regarding the reduction of the risks in developing conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Older Adults

Most in this age group or approaching this age group tend to prioritise maintaining their cognitive abilities as their goal. As was mentioned earlier we have shown the benefits habitual physical activity can have on the cognitive function.

Additionally, it is important to consider decreasing sedentary behaviour as physical inactivity leads to increased risk of all-cause mortality whether it’s an increase in risk of developing cardiovascular disease or respiratory complications (Katzmarzyk and Lee, 2012). Maintaining physical activity is also the cornerstone of maximising self-sufficiency. This may seem paradoxical at first for those who have decreased mobility and independence, but by encouraging whatever level of physical activity it will nonetheless carry some benefit as opposed to none. Habitual activity ensures the maintenance of adequate levels of flexibility, balance and exercise tolerance (Nelson et al. 2007) so as to negotiate ADL, this can translate to an effect that reduces the incidence of falls.

Guidelines[edit | edit source]

| link | link | link | link | link |

Risks of Physical Inactivity[edit | edit source]

Prescription[edit | edit source]

The prescription is likely to be the most difficult stage for the prescribing physiotherapist. Whilst this may seem daunting this is also perhaps the most creative/inventive part of the whole process in helping the patients become more physically active and decrease inactivity.

Two key issues will test both the physiotherapist and the patient:

- Uptake of adequate levels of physical activity

- Adherence to adequate levels of physical activity

Those that have chanced upon the film Field of Dreams will likely recall the optimistic phrase “If you build it, he will come”. Whilst we all need to have faith and trust in our patients, as physiotherapists we must practice our art with the highest degree of efficiency and efficacy. Thus, when it comes to physical activity prescription it is not enough to rely on the assumption that:

- “If you recommend exercise, they will do it…”

- “If you write a programme, they will follow it…”

Handcock & Jenkins (2003)

Linke et al. (2012) have reported that attrition rates in the general population who begin an exercise program are as high as 50% within the first 6 months. Whilst no recent studies have looked at attrition rates in sedentary individuals that have taken up a physical activity scheme or an exercise program, we cannot ignore the fact that without adequate support and appropriate prescription adherence will remain a tremendous issue.

Whilst it is unrealistic to expect all patients receiving a prescription of physical activity to see it through to the end it is both our duty and goal to maximise the chances. It is therefore important to tailor the prescription to be SMART and personalised [? Sentence referring to consideration for above sections].

An exercise prescription may be thought of as having the following basic components but should always be considered in tandem:

Mode[edit | edit source]

Is the type/form of physical activity that may be undertaken after consultation with the patient taking into account of their goals as well as interests and hobbies. In determining the mode one may be guided by considering the Frequency, Intensity and Time (FIT) components:

Frequency[edit | edit source]

May be considered as the number of occurrences of a particular physical activity during the day OR the number of days dedicated to a particular physical activity programme.

Guideline: Physical Activity targeting cardiorespiratory endurance (aerobic) is recommended 3-5 days a week (ACSM; Swedish). Significant improvements begins to plateau if frequency exceeds 5 days a week (Garber 2011), however this may be ameliorated by practicing a variety of physical activities. Similarly physiotherapists must also instil in their patients a good sense of pacing as discussed earlier [discuss in education?]. This allows the decrease in unnecessary injury through excessive high frequency of high intensity activities.

Additionally, whilst our roles are to encourage the frequency of physical activities of our patients and the general public it is equally important to encourage a decrease in the frequency a person is physically inactive. It is a matter of strategising and prioritising as to what is feasible. It may sometimes be helpful to ease certain individuals into a more active lifestyle

Intensity[edit | edit source]

Interpreted as how ‘vigorous’ a physical activity is. Garber et al. 2011 denotes there to be a positive dose response of derived health benefits from increasing physical activity intensity. Furthermore, it is also important to note the applicability of the “progressive overload” principle with regards to intensity levels. Just like training a particular muscle, physical activity levels below certain minimum intensity is unlikely to elicit any beneficial physiological changes (Garber 2011; Mason 2013).

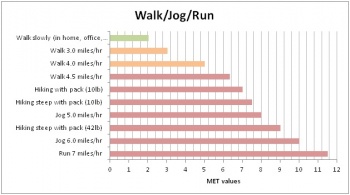

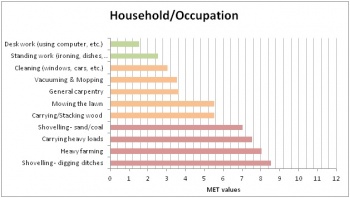

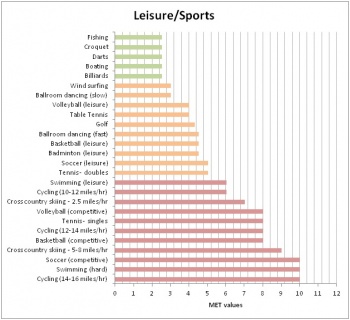

There are a number of measures scientists and health professionals have used to quantify the relative intensity levels of differing physical activities. These have included:

- VO2R = Percentage of oxygen uptake reserve.

- HRR = Heart Rate Reserve.

- VO2 = Oxygen consumption.

- HR = Heart Rate.

- MET = Metabolic Equivalents.

Whilst each of these relative methods of quantifying intensity has its advantages and disadvantages being acquainted with the concept of Metabolic Equivalents (MET) may help in giving an overview of what may be suitable.

The MET is a convenient and easily understood way of conceptualising the energy cost of physical activities as a multiple of resting metabolic rates (Jetté et al. 1990). The following tables summarises the relative Intensity with respect to the Mode of activity.

| |

| |

| |

| Figure. | |

Time[edit | edit source]

Is the measure in minutes or hours expended for a particular physical activity. A great majority living a sedentary lifestyle or those working to become more physically active often quote time as a barrier. Whilst it is easy to brush this off as mere excuses we must acknowledge that everyone has different priorities and won’t necessarily coincide with the aims you as a physiotherapist would like to achieve. It is then of great importance that as physiotherapists we need to educate our patients and the public of the current evidence-based guidelines regarding amount of time spent on physical activity.

As recommended in the Start Active, Stay Active report published in 2011 adults should aim to accumulate at least 150 minutes of physical activity of moderate intensity on at least 5 days of the week. What is important to note is the flexibility in structuring physical activity into sessions and need not be greater than 10 minutes. Patients that are previously sedentary and needing to ease into a more active lifestyle pursuing just 20 minutes of exercise per day can provide health benefits (ACSM 2013)

Risk Assessment[edit | edit source]

There is an inherent risk to everything we do it is a part of life. There is no certain policy, only the best available policy. Therefore, insofar as evidence has shown and sound clinical reasoning allows the benefits of encouraging and pursuing physical activity far outweighs the risks.

Like all other areas of physiotherapy practice the same standard of risk assessment and manual handling is required. The suitability of physical activity depends both on the presenting patient and sound judgment of the prescribing specialist. As physiotherapist we are in excellent position in our knowledge and skills to take advantage and adapt a safe and achievable physical activity programme.

When considering the risks, contraindications and feasibility of prescribing physical activity we must contemplate the following:

- Individuals who are healthy but sedentary.

- Individuals that are apparently health and sedentary.

- Individuals with comorbidities.

- Individuals with a disability.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) has been an effective method for health professionals to assess individuals with disability in reintegrating back with society or identifying areas that needs greater existence. It is a great tool when addressing the issues of physical inactivity amongst people with disabilities as highlighted by Rimmer (2005). The same model can theoretically be used as an adapted template to help clinicians draw out the key areas/issues when making a risk assessment as to what may be suitable for the individual.

[Insert ICF model ppt.]

Comorbidities

1) In general exercise very rarely provokes a cardiovascular event in apparently healthy individuals with normal cardiovascular systems (ACSM 2013).

2) However, evidence indicates an acute and transient increase in the risk of sudden cardiac death and/or myocardial infarction in individuals performing vigorous intensity exercises with diagnosed or occult CVD. Nonetheless, such occurrences remain a rarity.

Additionally there is clear evidence of a dose-response relation between physical activity and health. Whilst this is not strictly a risk assessment of physical activity it is worth considering the risk of physical inactivity when weighing up the advantages and disadvantages, and is worth educating the public about.

Resources[edit | edit source]

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY: THE COMMUNITY AND GOVERNMENT POLICY[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists can have an influence in all these dimensions and should take a multifactor approach to activity promotion-from individual interventions, to community input all the way up to government policy development.

Community[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists are in a place to have community/public health roles as well. A large systematic review assessed the effectiveness of various community wide physical activity interventions[45]. These ranged from signs promoting stair use to school based interventions encouraging limited television and video game time[45]. They concluded that community wide programmes regarding health education, school-based physical education, and social support were very effective interventions, again emphasizing that physical inactivity is a vast problem and it needs a multipronged approach in order to be successful[45].

Physiotherapists can be creative in how they get involved in promoting physical activity education. Below are some examples of physiotherapist led community programmes that promote physical activity and target populations with varying needs.

Babies to teens:

- Kidilates-pilates for infants and young kids even with disabilities

- Ready Steady Go Kids-preschool multi-sport

- Physiocise-kids and teens

Adults:

- PhysioledPilates

- Back to Fitness NHS service

Older Adults:

Volunteering[edit | edit source]

Home[edit | edit source]

There are 111 volunteering roles in the health and social care sectors ranging from roles in administration to teaching PA classes[46].

- Crisis, the national charity for homeless individuals, look for physiotherapists to volunteer and provide services such as assessments, advice, treatments and referrals to additional services for their clients over the Christmas period[47].

- The Riding for the Disabled Association has a selection of volunteering positions that vary from administration duties, instructing and physiotherapy[48].

Abroad[edit | edit source]

It was estimated by the United Nations Development Programme that over 80% of the world’s 650 million disabled people reside in impoverished countries with little access to rehabilitation facilities, education, and employment. Overseas organisations are looking for physiotherapist for the development of rehabilitation services both in hospitals and in community based clinics.

Oppurtunties for CPD:

These are just a few of the many examples that physiotherapists can take up as an added role or make community education a more main role in their career as able. Physiotherapists have many continuing education opportunities available to them that may help them find a new role, such as pilates certificate, specialising in women’s health (e.g. antenatal exercise classes), paediatrics, long term conditions etc.

Government and Policy[edit | edit source]

Role in Public Health[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation highlights the requirement for supplementary preventative health programmes in order to combat the emergence of lifestyle related ailments and long term disorders.

Karen Middleton, AHP lead at the Department of Health in England, has recognized governance in public and preventative health as a difficulty for physiotherapy[48].

Public Health Service Examples:

1. Planning of education programmes for the promotion of the role of the physiotherapist in public health.

2. Assisting physiotherapists in their advising roles on PA.

3. Collaboration with Exercise on Prescription Instructors in Chronic Pain Services.

4. Promotion of the use of stairs in an NHS hospital.

5. Daytime yoga classes for individuals with a physical disability.

Consultant Role in Policy[edit | edit source]

Band 8 Physiotherapy Consultants act as clinical physiotherapist leads within a specialist service while assessing and treating their own specialist caseload of patients. In addition, they have a role in clinical governance providing physiotherapy guidance within organisations and out with, while also partaking in research[49].

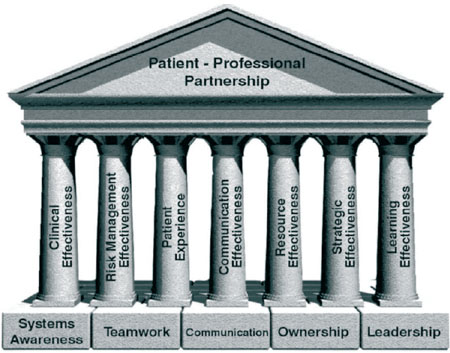

Clinical Governance

[edit | edit source]

"Clinical governance is a system through which NHS organizations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish."[50]

Clinical governance is a term used to describe the broad range of activities that assist in the sustenance and improvement of high quality patient care. It is the responsibility of healthcare organisations, to the public they serve, that care delivered is safe and of the highest quality. In regards to implemented systems, structures and actions implemented healthcare organizations are required to produce evidence that standards are being maintained. In order to determine whether physiotherapists are delivering best quality of care in regards to PA an active role in research, service evaluation and clinical audit is crucial.

Pillars of Clinical Governance[51]:

Research[edit | edit source]

Research is the about the acquisition of new information and the discovery of which treatments and mode of care produce the best effects. It gives us direction on what we should be doing in our clinical practice. Clinical audit addresses the quality of care and whether best practice is being implemented, if what needs to be done is being applied and how well is being done[52].

Transitional research describes the procedure of applying and extending the results of basic research beyond the clinical research setting to clinical practice and finally to health policy ie. From bench to bedside to community settings thus targeting public health[53].

Service Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Service evaluation aims to interpret and evaluate current care. It is designed to identify what type of standard a current service achieves[54].

Clinical Audit

Carried out in order to provide information to better equip the delivery of best practice and care for the patient, clinical audit addresses the question whether a service meets a predetermined standard[54].

Clinical Audit Process[55]

Resources:

The NICE Physical Activity Pathway gives an in depth and interactive overview of tackling the issue of physical activity in the workplace, through local services and education, NHS services, government and policy, and training.

KEY RESOURCES[edit | edit source]

REFERENCES[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century [warm up].J Sports Med 2009;43(1):1-2.

- ↑ Khan KM, Tunaiji HA. As different as Venus and Mars: time to distinguish efficacy (can it work?) from effectiveness (does it work?) [warm up] . Br J Sports Med 2011;45(10):759-760.

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO).Prevalence of physical inactivity 2013; Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO).Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) 2013; Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380(9838):219-29.

- ↑ Hallal PC, Bauman AE, Heath GW, Kohl HW, Lee IM, Pratt M. Physical activity: more of the same is not enough [comment] . Lancet 2012;380(9838):190-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380(9838):247-57.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Kohl HW 3rd, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet 2012;380(9838):294-305.

- ↑ Department of Health. Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers 2011; Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/start-active-stay-active-a-report-on-physical-activity-from-the-four-home-countries-chief-medical-officers Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Paffenbarger RS Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM. A history of physical activity, cardiovascular health and longevity: the scientific contributions of Jeremy N Morris, DSc, DPH, FRCP. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(5):1184-92

- ↑ Naci H, Ioannidis JPA. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ 2013;347:f5577.

- ↑ DocMikeEvans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo [last accessed 18/11/13]

- ↑ Risk Bites. Is sitting on your backside dangerous?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COIGHiMveG4 [last accessed 26/11/13]

- ↑ Petty, N.J. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. 2001. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Hussey J, Wilson F. Measurement of Activity Levels is an important part of physiotherapy assessment. Physiotherapy 2003;89(10):585-93.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Sallis, R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;45:473-4

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Khan KM, Weiler R, Blair SN. Prescribing exercise in primary care. BMJ 2011; 343

- ↑ AHIPResearch. Kaiser Permanente: Making Exercise a Vital Sign. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hxfp0LOaLMM [last accessed 03/13/13]

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Quality Assurance Standards 2012. Available at: fckLRhttp://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/professionalism/csp-expectations-members/quality-assurance-standards (accessed 3 November 2013).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPAHASPASQ - ↑ 21.0 21.1 Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380(9838):258-71.

- ↑ Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR Jr, Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behaviour. J Phys Act Health 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11-8.

- ↑ Jonas S, Phillips EM. ACSM’s Exercise is MedicineTM: A Clinician’s Guide to Exercise Prescription. American College of Sports Medicine 2009 Philadelphia

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther 1993;73(11):771-82.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Steptoe A, Kerry S, Rink E, Hilton S. The impact of behavioural counselling on stage of change in fat intake, physical activity, and cigarette smoking in adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):265-9.

- ↑ Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Medicine 2013:1-10.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part II): Evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):354-68.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behaviour change in primary care. Am J Prev Med 1999;17(4):275-84.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Prochaska JO and DiClemente CC. Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward An Integrative Model of Change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(3):390-5.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Nigg CR, Geller KS, Motl RW, Horwath CC, Wertin KK, Dishman RK. A research agenda to examine the efficacy and relevance of the transtheoretical model for physical activity behaviour. Psychol Sport Exerc 2011;12(1):7-12.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Shinitzky HE, Kub J. The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs 2001;18(3):178-85.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rhodes RE and Fiala B. Building motivation and sustainability into the prescription and recommendations for physical activity and exercise therapy: The evidence. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):424-41.

- ↑ Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman, 1997.

- ↑ O’Hea EL, Boudreaux ED, Jeffries SK, Carmack Taylor CL, Scarinci IC, Brantley PJ. Stage of change movement across three health behaviors: the role of self-efficacy. Am J Health Promot 2004;19(2):94-102.

- ↑ Dishman RK, Motl RW, Sallis JF, Dunn AL, Birnbaum AS, Welk GJ, Bedimo-Rung AL, Voorhees CC, Jobe JB. Self-management strategies mediate self-efficacy and physical activity. Am J Prev Med 2005;29(1):10-8.

- ↑ Al-Otaibi HH. Measuring stages of change, perceived barriers and self efficacy for physical activity in Saudi Arabia. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2013;14(2):1009-16.

- ↑ Nothwehr F, Yang J. Goal setting frequency and the use of behavioural strategies related to diet and physical activity. Health Educ Res 2007;22(4):532-8.

- ↑ Shilts MK, Horowitz M, Townsend MS. Goal setting as a strategy for dietary and physical activity behaviour change: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 2004;19(2):81-93.

- ↑ DiClemente CC, Marinilli AS, Singh M, Bellino LE. The role of feedback in the process of health behaviour change. Am J Health Behav 2001;25(3):217-27.

- ↑ CSP Facilitating Behaviour Change, Evidence Briefing. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/facilitating-behaviour-change-evidence-briefing (accessed 19 Nov 2013).

- ↑ NHS Health Scotland. Physical Active Pathway For Secondary Care. Available at: http://www.healthscotland.com/documents/21759.aspx (accessed 21 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Miller WR and Rollnick S. Ten Things that Motivational Interviewing Is Not. Behav Cog Psych 2009;37(2):129-40.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Martins RK and McNeil DW. Review of Motivational Interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29(4):283-93.

- ↑ Resnicow K, DiIlorio C, Soet JE, Borrelli B, Hecht J, Ernst D. Motivational Interviewing in Health Promotion: It Sounds Like Something Is Changing. Health Psychol 2002;21(5):444-451.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, Stone EJ, Rajab MW, Corso P, and the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2002;22(4S):73-107

- ↑ VSO. Physiotherapists: Volunteer opportunities overseas for physiotherapists. Available at: http://www.vso.org.uk/volunteer/opportunities/community-and-social-development-health/physiotherapists (Accessed 23 November 2013).

- ↑ Crisis. Specialist Volunteers: Physiotherapy. Available at: http://www.crisis.org.uk/pages/service-volunteers.html#physiotherapy (Accessed 24 November 2013).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 CSP Move for Health. Physiotherapy Public Health Service Examples. 2013. Available at: http://www.csp47.co.uk/framework/sites/default/files/Move%20for%20Health%20exemplars1-5.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2013).

- ↑ NHS. National Profiles for Physiotherapy. 2005. Available at:fckLRhttp://www.nhsemployers.org/PayAndContracts/AgendaForChange/NationalJobProfiles/Documents/Physiotherapy.pdf (Accessed 24 November 2013).

- ↑ Scally G, Donaldson LJ. Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. British Medical Journal.1998; 317(7150): 61-65.

- ↑ Nicholls S, Cullen R, O’Neill S, Halligan A. Clinical governance: its origins and its foundations. British Journal of Clinical Governance. 2000. 5 (3):72 – 178.

- ↑ Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. What is the difference between clinical audit and research? 2012 [online] Available at: http://www.hqip.org.uk/what-is-the-difference-between-clinical-audit-and-research/ (Accessed 24 November 2013).

- ↑ Seals D.R. Translational physiology: from molecules to public health. Topical Review. The Journal of Physiology. 2013; 591(14):3457-69.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 National Research Ethics Service. Differentiating audit, service evaluation and research. 2006. Available at:fckLRhttp://www.nres.nhs.uk/applications/guidance/?EntryId62=66988 (Accessed 24 November 2013).

- ↑ Research & Professional Development. Available at: http://www.rpd-research.org.uk/about.html (Accessed 28 November 2013).

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

![[1]](/images/e/eb/GAPALogo.jpg)

![[2]](/images/f/f7/ParticipActionLogo.jpg)

![[3]](/images/5/5d/GetIrelandActive1.jpg)

![WHO Guidelines[4]](/images/thumb/4/4a/WHOFlag.png/257px-WHOFlag.png)

![US Guidelines[5]](/images/thumb/d/de/Flag_of_the_United_States.png/342px-Flag_of_the_United_States.png)

![UK Guidelines[6]](/images/thumb/5/5b/UKFlag.png/360px-UKFlag.png)

![Irish Guidelines[7]](/images/thumb/5/54/Flag_of_Ireland.jpg/360px-Flag_of_Ireland.jpg)

![Canadian Guidelines[8]](/images/thumb/b/b6/Flag_of_Canada.png/360px-Flag_of_Canada.png)

![Australian Guidelines[9]](/images/thumb/c/c1/Flag_of_Australia.png/360px-Flag_of_Australia.png)

![New Zealand Guidelines[10]](/images/3/34/Flag_of_New_Zealand.png)

![[11]](/images/7/76/CSPLogo.jpg)

![[12]](/images/e/ee/WCPTLogo.jpg)

![[13]](/images/f/fd/PAHA-AHPPledge.jpg)

![The Individual[14]](/images/2/24/IndividualLogo.jpg)

![The Community[15]](/images/thumb/8/86/CommunityLogo.jpg/239px-CommunityLogo.jpg)

![Government & Policy[16]](/images/thumb/1/1d/GovernmentLogo.jpg/187px-GovernmentLogo.jpg)

![Physical Activity Resource Center for Public Health[17]](/images/thumb/c/c4/UniofPitss.jpg/180px-UniofPitss.jpg)

![[18]](/images/e/e7/HBCRLogo.jpg)

![[19]](/images/e/ea/ACELogo.jpg)

![[20]](/images/3/35/NHSEduforScot.jpg)

![[21]](/images/c/c6/VolunteeringEngland.jpg)

![[22]](/images/7/7f/RDA.jpg)

![[23]](/images/3/32/VolunteerCRISIS.jpg)

![[24]](/images/3/31/AbroadVSO.jpg)