Tackling Overprescription: Difference between revisions

Debbie Kenny (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Debbie Kenny (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Throughout this resources you will be provided opportunities to: | Throughout this resources you will be provided opportunities to: | ||

[[File:Stop-and-Think-cartoon small.jpg|left|frameless]] | * [[File:Stop-and-Think-cartoon small.jpg|left|frameless]] | ||

Reflect on your own practice experience and clinical knowledge to consider the relevance of the information within your own field of work. | |||

Reflect on your own practice experience and clinical knowledge to consider the relevance of the information within your own field of work. | * [[File:Screen Shot 2018-04-06 at 2.59.20 PM.png|left|frameless|204x204px|border]] | ||

[[File:Screen Shot 2018-04-06 at 2.59.20 PM.png|left|frameless|204x204px|border]] | |||

Continuing Professional Development will offer supplementary links to further your understanding on a given topic through current evidence based journal articles. | Continuing Professional Development will offer supplementary links to further your understanding on a given topic through current evidence based journal articles. | ||

[[File:Quiz time.jpg|left|frameless|164x164px]] | * [[File:Quiz time.jpg|left|frameless|164x164px]] | ||

Take quizzes to consolidate your learning and maybe challenge coworkers to teach those around you. | Take quizzes to consolidate your learning and maybe challenge coworkers to teach those around you. | ||

Revision as of 14:57, 17 April 2018

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Should we put a brief introduction here to highlight what we're suggesting is the problem, and highlight the purpose of this wiki then go into Peter's section with more detail

Throughout this resources you will be provided opportunities to:

Reflect on your own practice experience and clinical knowledge to consider the relevance of the information within your own field of work.

Continuing Professional Development will offer supplementary links to further your understanding on a given topic through current evidence based journal articles.

Take quizzes to consolidate your learning and maybe challenge coworkers to teach those around you.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

This resource will enable the reader to:

- Define deprescription and its relevance to the Health Care system

- Explain the role of the physiotherapy profession in deprescription

- Justify the value of deprescription within AHP’s and its application within health care

- Recognize populations at risk of over-prescription and identify common clinical problems/scenarios and medications involved

- Rationalize appropriate non-pharmacological alternatives

- Explain how multidisciplinary teams can work together to better promote/apply deprescription

- Evaluate one’s own practice in relation to the movement of deprescription

Audience[edit | edit source]

This resource is intended for qualified or pre-reg student physiotherapists who are interested in recognizing clinical circumstances of overprescription and further educating themselves on the potential role that could play is addressing this growing issue. All other allied health professionals, academics or individuals interested in the topic are also welcome.

Overview of medication over prescription[edit | edit source]

According to current health projections, due to an increasingly ageing population, the prevalence of multi-morbidity in the UK is predicted to rise significantly[1]. Multi-morbidity can be described as the presence of two or more chronic medical conditions in an individual[2]. Over the next twenty years, the prevalence of multi-morbidity is predicted to increase by 26% in the 65-74 age group, 64.5% in the 75-84 age group and 211% in the 85+ age group[1]. With each morbidity or disease, there are different recommendations for treatment medications in accordance with disease-specific guidelines. Whilst guidelines are readily available, they are very much tailored to be disease-specific. The guidelines do not modify or consider the applicability for patients taking medications for multi-morbidity, where adhering to guidelines for each and every drug will inevitably lead to overconsumption of medications[3]. This over consumption of medications is commonly known as ‘Polypharmacy’.

Despite the topical use of the term polypharmacy to describe the use of multiple medications, a clear definition is still lacking. Some authors define polypharmacy as taking more than five medications[4], whilst others define polypharmacy as taking medication which lacks an indication, is ineffective, or duplicating the treatment offered by another medication.[5] The term polypharmacy itself should not be used as a universal term, but instead be considered as either ‘Appropriate’ or ‘Problematic’ polypharmacy.[6] Appropriate polypharmacy are medicines which, when prescribed according to best evidence, can extend life expectancy and improve quality of life, by treating a specific condition or illness. However, problematic polypharmacy is the inappropriate prescribing of multiple medicines, or where the intended benefit of the medicines are not realized.[7] According to research, problematic polypharmacy increases the risk of interactions and adverse drug events (ADEs) as well as affecting patient compliance and quality of life. [6]

This lack of clarity reflects the difficulty in setting an accurate cut-off point for not only when polypharmacy begins, but also at which point polypharmacy becomes problematic. According to a review of [4], the most common point at which polypharmacy is considered to begin is the use of more than five medications[4]. If applying the cut-off point outlined by[4], research highlights that in certain settings, between twenty-five and fifty percent of all patients aged seventy-five or older are exposed to polypharmacy on a daily basis.[8][9][10][11] Factors such as patient age, updated medication treatment criteria, cross-activity, interference and effect on metabolism should be considered when trying to determine if the patient’s polypharmacy is appropriate or problematic. [6]

Research has suggested that problematic polypharmacy is associated with multiple negative consequences, for both health and finance. Consequences associated with problematic polypharmacy include:

- Increased risk for ADEs. [12][13]

- Reduced functional capacity [14]

- Reduced cognitive impairment [15]

- Increased risk of falls [16]

- Negative affect on nutritional status [15]

- Overall increased risk of mortality [17]

- Increased health care costs for both the patient and the health care system [18]

Problematic polypharmacy is generally seen as the result of a cascade of prescribing. [5] This cascade is often initiated when an adverse drug effect is misinterpreted as a new medical problem, leading to the prescribing of more medication to treat the initial drug-induced symptom(s). Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) (medications which should be avoided in older adults and those with certain health conditions), are also increasingly probable to be prescribed in the setting of problematic polypharmacy. [5][19]Means to addressing problematic polypharmacy has long been a topic of interest, and according to Moriarty et al. (2017), the majority of consequences of problematic polypharmacy can be minimized or even prevented by using a patient-centered, structured process with planning, tapering and close monitoring during, and after medication withdrawal. According to literature, this process is known as Deprescribing. [20]

Deprescribing[edit | edit source]

Deprescribing is defined as the process of withdrawal (and/or dose reduction) of inappropriate medications supervised by a health care professional.[21][22] The term “Deprescribing” first appeared in literature in 2003 [23]. The term has become more widespread in recent years, with literature recommending that the term Deprescribing should be internationally adopted in order to create a universal understanding, both in research and practice, of this specific concept of medication withdrawal or reduction. [24]

The following videos provides an easy to follow in-depth discussion regarding the concept.

With increasing concern about the negative effects of overuse of medications, there in growing attention being paid to approaches which can minimize harm and promote healthy wellbeing. Focus is shifting from prescribing, which is the starting or renewing of medications, toward this concept of Deprescribing, especially within an ageing population (Reeve et al. 2017). It is very important to note that Deprescribing is very different to non-adherence or non-compliance. Desprescription involves health care professional direction and supervision with the same level of expertise and attention that prescribing entails. [21]

As well as the misinterpretation of symptoms discussed previous, whilst medications may be prescribed and initiated for an appropriate reason, potential insufficient monitoring, follow-up, and transfer between providers and care settings may contribute to medications being continued indefinitely and inappropriately. [20] According to research, there are high levels of inappropriate medication use in older adults across a variety of settings and countries, proposing that there are currently vast unrealized opportunities for Deprescription[25][26]. As well as opportunity, research suggests there is a desire for this desire for this concept of deprecribing to be introduced. Despite a moderate agreement in the specific medicines to deprescribe, a study by Page et al. (2016) found that both physicians and pharmacists in the study had ‘substantial’ agreement that desprecribing is beneficial for the patient[27]. As well as Health Professionals, research suggests that older individuals themselves are “eager” to undertake deprescribing [28]. The authors’ suggested that this desire was linked to the individuals’ feeling of taking a large number of medications and with the belief that some of the medications were no longer necessary. [28]

With an increasing interest in deprescribing, this resource aims to provide understanding of the potential role that the Physiotherapist can play in this growing concept

Take a moment to complete this short quiz to to see how much you've learned about polypharmacy in our current health care system and society.

The Potential Role of the Physiotherapist in Deprescribing[edit | edit source]

The authors of this resource are students of Physiotherapy, and not Supplementary Prescribers (SPs) or Independent Prescribers (IPs). Therefore the discussion of the role of the Physiotherapist in supplementing alternative and complimentary options to polypharmacy will be approached whilst considering our scope of practice.

As an emerging role, the role played by the Physiotherapist in Deprescribing has previously not been examined, to the knowledge of the authors. Therefore, this resource aims to investigate the potential role the Physiotherapist can play in this growing concept.

Available literature linking physiotherapy with deprescribing has focused only on the role of physiotherapy as a supplementary treatment for pain relief when reducing opioid dosage.

Research [29][30][31] suggest that patients in severe pain, despite use of high-dose opioids, may experience significant improvement in pain severity, functioning, and mood when their opioid is tapered to a lower, safer dose. In this research, opioid-dose reduction was supplemented by interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs, including physiotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy and occupational therapy, which showed long-term improvements in pain, functioning and emotional health[29][30][31]. There was no distinction of which individual treatment modality was most effective however these studies highlight the potential for a multi-disciplinary approach to deprescription. In addition, guidelines for opioid use recommend that patients with long term complex pain should have their opioid dosage regularly reviewed, with removal or reduction of opioids supplemented with non-opioid analgesics or non-drug treatments such as physiotherapy, where appropriate. [32][33]

This resource aims to bridge a gap in literature by investigating the potential role the Physiotherapist can play in the deprescribing process itself.

Have you ever considered the potential role for allied health professionals in deprescription? If so, how did you envision it?

Deprescribing in Other Health Care Professions[edit | edit source]

As well as identification of polypharmacy, there are other roles to share in the deprescription process. [21] Literature suggest that the following elements are fundamental in the process of Deprescribing. [34][35]

- Collect a complete and comprehensive medication history

- Assess overall risk of harm and benefit and individual patient factors which may affect deprescribing

- Identify potentially inappropriate medications

- Decide on medication withdrawal

- Plan tapering or withdrawal process and monitoring with documentation and communication to all persons relevant to care

- Conduct monitoring and support

- Documentation

Whilst the elements are easily classifiable, the specific profession of the multidisciplinary team responsible for each is not as easily distinguished. Instead, much of the available literature recommends sharing the process.

Shared, informed decision making is crucial to delivering patient-centered care, and it is just as important to delivering Deprecription. [21] While some patients evidently may still seek recommendation from their physician, or seek their physician to make decisions regarding medication[36][37], shared multidisciplinary decision making can still occur through discussion of options, benefits, harms and consideration of patient preferences. [38] When Deprescribing medication(s), patients’ should be provided with sufficient knowledge of the decision to be made, have realistic expectations for outcomes and be confident in their decision. [39] Members of the multidisciplinary team are ideally located to play a part in this process.

As well as physicians, general practitioners (GPs), nurses, medical specialists and pharmacist have all been highlighted in the literature to being involved in leading or contributing to deprescribing efforts. Research indicates that multidisciplinary interventions are generally the most effective at reducing polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use. [21] [40] Research recommends that pharmacists and nurses be involved in the deprescribing process in practice. The author suggests that patients are generally more comfortable with the involvement of a pharmacist or nurse in the process of deprescribing. [41]

Evidence suggests that patients are more willing to have a medication deprescribed if it is recommended by a health professional whom they have a relationship with. [42][43][44] The health professionals elucidated in the studies were physicians, GPs and medical specialists. Furthermore, research suggest that interventions with close involvement of the local GP are more likely to be successful in achieving deprescribing than those which are conducted by an external research team. [34] When considering the avenue of GP desprecribing, it must be noted that the primary care setting provides access to prescription history and medical records and provides opportunity for monitoring after discontinuation, which the GP cannot offer. Evidence recommends that effective communication between GP’s and specialists with access to this information may serve as a viable solution to this issue [45].

Regardless of specific elements or mechanical tasks in the Deprescribing process, it is clear from the evidence that sharing the process amongst the multidisciplinary team provides the greatest platform for success.

The following sections will provide in-depth discussion regarding the potential roles that the Physiotherapist could play in this deprescribing process.

Benefits and Harm of Deprescription[edit | edit source]

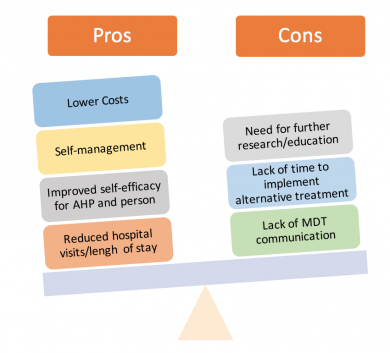

This next section highlights the relevant evidence both in support of and against the potential for deprescription as a treatment option from the patient and AHP perspective.

The Patient's Perspective[edit | edit source]

92% of older adults are hypothetically willing to decrease the amount of medication they are taking. One concern is this “willingness” may not transfer to real life when it comes to actually implementing deprescription (Reeve et al. 2013a; Qi et al. 2015; Kalogianis et al. 2016; Reeve et al. 2016b).

Patients are presently more willing to try deprescription if their doctor is the one to suggest it or if it comes from another medical practitioner they have a strong relationship with (Reeve et al. 2013b; Linksy et al. 2015; Reeve et al. 2016a).

- This could be a role for physiotherapists in the future if we change how patients’ view the various role differences in allied health professionals.

Patients’ concerns with deprescribing are: not believing it’s appropriate for them and fear related to withdrawal. (Reeve et al. 2013b; Linksy et al. 2015; Reeve et al. 2016a; Reeve et al. 2016b).

- This could be addressed with effective communication that educates the patient on the appropriateness of deprescribing.

Patients want to understand their medication better, and an increase in their knowledge on medication could help resolve some adverse reactions from occurring and improve patient adherence (Reeve and Wiese 2014)

- Following pharmacist led medication reviews, patients found they understood more, were content with decisions and overall felt like they had a better quality of life (Jokanovic et al. 2017a).

In areas where healthcare is not free, patients felt that if they didn’t need to be on numerous medications or potentially no medications, there would be less out of pocket costs (Reeve and Wiese 2014).

- Kalogianis et al. (2016) found 14.7% of people in residential aged care facilities within Australia, stated that paying less for medication would positively affect their willingness to try deprescription.

Looking back on the individuals you've worked with, can you think of anyone that would have been keen to explore the potential of reducing their prescription or some that would have resisted out of concern?

The Allied Health Care Perspective[edit | edit source]

CON’s

- It has been PROVEN polypharmacy has NEGATIVE health benefits such as: decreased quality of life, adverse drug reactions, increased fall occurrence, hospitalization, mortality and non-adherence (Hajjar et al. 2007; Olsson et al. 2011; Jyrkka et al. 2012; Maher et al. 2014; Wallace et al. 2017).

- Passarelli et al. (2005) found inappropriate medications doubled a patient’s chance of adverse reactions.

- Antiplatelet drugs, insulin, warfarin and hypoglycemics have been found to be a cause of 2/3 of adverse drug reactions in hospitals (Budnitz et al. 2011).

- Polpharmacy burdens healthcare providers by the constant rise in demand for medical administration, which limits the staff’s time for provision of non-pharmacological care (Kalogianis et al. 2016). Unfortunately, it is suggested that fragmented healthcare systems are barriers to multi-disciplinary team communication in the implementation of deprescription (Reeve et al. 2014; Mudge et al. 2015).

Negative consequences include exacerbation of underlying diseases and drug withdrawal symptoms (Iyers et al. 2008). Adverse drug withdrawal events can occur (ex. insomnia when decreasing benzodiazepines or rebound heartburn when stopping protein pump inhibitors), but serious harm is rare (Graves et al. 1997; Marcum et al. 2012; Paquin et al. 2014).

PRO's

- Numerous studies have proven to lower costs in healthcare in relation to deprescription (Holland et al. 2008; Jokanovic et al. 2016; Jokanovic et al. 2017a). The funding saved from deprescription can then be used on other interventions (Williams et al. 2004; Garfinkel et al. 2007; Kutner et al. 2015).

- Estimated savings of $716.46 US per participant on a generic statin can be achieved when the drug is removed (Kutner et al. 2015). Follow-up on their study showed that most participants remained off the drug.

- Proven clinical outcomes with deprescription have also been displayed in patients with diabetes and high blood pressure, which resulted in better cholesterol control and overall medication management (Jokanovic et al. 2017a).

- When reviewing individualized withdrawal of inappropriate medications, it was found that only 2-18% of patients actually restart medication due to reoccurrence of the condition or symptoms (Garfinkel et al. 2007; Garkinfel and Mangin 2010)

- 14-64% of patients successfully discontinued their proton pump inhibitors (Haastrup et al. 2014), 25-85% of patients discontinued benzodiasepines, but when discontinuing antihypertensive medication 15-80% of patient restarted medication before the end of the study (Iyer et al. 2008; Paquin et al. 2014)

- Declercq et al. (2013) found that withdrawal symptoms DO NOT have a significant effect on behavior in the patient population with dementia, when reducing/removing their antipsychotics

- This emphasizes the need to review the appropriateness of which drugs are most tolerated when deprescribed, but it is promising for future outcomes in deprescription.

- By simply removing unnecessary or inappropriate patient medication in palliative care could offer public health benefits (Holmes et al. 2008; Jokanovic et al. 2017b).

- In the US, 177,504 emergency hospital visits during 2004-2005 occurred by adverse drug reactions in adults over age of 65. (Jokanovic et al. 2017b; Budnitz et al. 2007)

- Australia = 30% unplanned hospital visits are from patients over 75 year old and ¾ of them are preventable (Runciman et al. 2003; Jokanovic et al. 2017b).

- Antiplatelet drugs, insulin, warfarin and hypoglycemics have been found to be a cause of 2/3 of adverse drug reactions in hospitals (Budnitz et al. 2011)

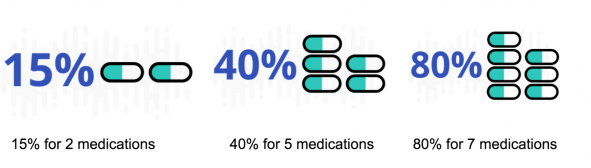

- Having ≥ 5 medications have been related to an increase of falls, frailty, delirium and disability in a geriatric population (Freyer et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2016; Senel et al. 2017). The table below is derived from data presented in Gnjidic et al. (2012) and Turner et al. (2016) research on the risk of falls while on varying amounts of drugs. {| class="wikitable" | |Sensitivity |Specificity |- |Risk of Falls on > 5 Medications |75.7% |44.5% |- |Risk of Falls on > 10 Medications |24.3% |85.5% |}

- In the US, 177,504 emergency hospital visits during 2004-2005 occurred by adverse drug reactions in adults over age of 65. (Jokanovic et al. 2017b; Budnitz et al. 2007)

Positive effects include: reduction of inappropriate drug use, overall medication numbers, decreased hospital lengths of stay, general health improvement and limits the decline in a patient’s quality of life (Scott et al. 2015).

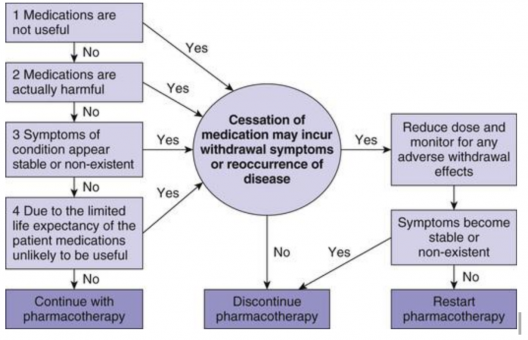

When it comes to implementing deprescription, healthcare providers may be undecided which medications should be decreased or removed. Algorithms such as the figure below from Page et al. (2016) were introduced to help target this issue. The implementation of decision-making guidelines for deprescription has increased healthcare professionals’ overall self-efficacy in the process (Farrell et al. 2018).

Click on the following link to see how much you've learned!

https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/DQ5C8GY

Knowledge and Skills Required to Have a Role in Deprescription[edit | edit source]

Current Ability to Prescribe[edit | edit source]

In order to have an understanding of the role of deprescription, physiotherapists must have an understanding of their current role and scope of practice with regards to prescribing medication. Currently there are two types of prescribers physiotherapists can be, this will be described below.

Physiotherapy prescribers have undertaken an additional qualification to their degree and are restricted to prescribing in their clinical speciality.[edit | edit source]

Supplementary Prescriber[edit | edit source]

The supplementary prescriber works in partnership with a doctor or dentist to prescribe the medicines needed by an individual patient for the management of their condition using a written document called a Clinical Management Plan (CMP). The names of the medicines permitted to be prescribed must be listed in a written Clinical Management Plan that is created before prescribing occurs. Although this means that there is no restriction in what medication can be prescribed the ultimate decision and responsibility in deciding on the medication lies with the doctor.

Independent Prescriber[edit | edit source]

Being an independent prescriber allows a physiotherapist to autonomously prescribe, as well as supply and administer medicines appropriate to the needs of the named patient.

Independent prescribers can be used to prescribe any licensed medicines from the British National Formulary (within local and national guidelines), they can mix medicines prior to administration and prescribe from a list of seven controlled drugs:

As well as prescribing medication independent prescribers can alter doses, cease to prescribe a medication and withdraw a medication. This must be within the restrictions as stated above and be thoroughly discussed with the patient. When withdrawing a medication a plan must be put in place that has been agreed in partnership with the patient.

If considering the benefit of ceasing or “deprescribing” a medication it may be useful to consider the protocol in Figure(?) to justify the changes. This may also apply to supplementary prescribers relaying information back to the doctor.

Current non- Prescribers expected knowledge and skills of medication:[edit | edit source]

The CSP advocate that non-prescribers, i.e. the majority of physiotherapists, at a minimum should be able to signpost patients to where they could obtain appropriate medication advice. Furthermore, non-prescribers are expected give advice on medication if they have detailed knowledge of medication in their specialised area or knowledge from previous education (i.e. pharmacology degree). Please note there is a big difference between giving advice and prescribing medication and when giving advice physiotherapists must:

- Have the appropriate knowledge of the medication, including its pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

- Absorption – how the drug gets into the body (unless injected intravenously)

- Distribution – once absorbed into the blood, where the drug goes

- Metabolism – how the body breaks the drug down into other compounds that are more easily excreted

- Elimination – how the drug is excreted and eliminated from the body.

- The legal frameworks surrounding medicine.

- Know where appropriate information regarding the medication can be obtained- in particular signposting the patient to inside the medication packet where the summary of product characteristics can be found.

General and Specific advice that non-prescribers can give:[edit | edit source]

General advice that can apply to the whole population may be given on the effects of medication. For example the general side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). While providing advice it should also be recommended that the patient should seek advice from a pharmacist or independent prescriber before altering any medication they currently take.

According to the CSP, specific advice may be given to patients in certain situations, for example:

“Physiotherapists may give advice and recommend taking paracetamol for MSK pain. There are several reasons for this- there is a substantial amount of evidence supporting this intervention including NICE guidelines and paracetamol is on the general sales list where patients can acquire this medication independently without a prescription.”

Please note: non-prescriber physiotherapists CANNOT provide tailored specific advice on prescription-only medication.

Physiotherapists can recommend patients to go and seek a specific medication from their GP. ONLY IF the physiotherapists have substantial knowledge of the prescription only medication, the evidence base behind it and is working with that particular relevant patient group. If the medication is advised it MUST be followed up with the recommendation that it must be discussed with their GP.

Patient taking their medication incorrectly? Advice non-prescribers can give:[edit | edit source]

If a non-prescriber physiotherapist notices a patient is not taking their medication correctly, they can refer the patient to the medications instructions and remind them how and when/ dose they should be taking their medication as prescribed. This can also apply to medication devices, e.g. an inhaler, advice can be given how to use it according to guidelines. Expected adverse effects of medication? What non-prescribers can do: Physiotherapists can refer the patient back to the GP/pharmacists or can contact the GP directly providing information on their concerns. When deciding whether a medication or combination of medications are may be harmful, the professional must consider (Reznik J. Pharmacology handbook for physiotherapists. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier Australia; 2017.)

- Patient’s age

- Medication treatment updated criteria

- Cross-activity

- Interference

- Effect on metabolism (length of effect)

- Toxicity (therapeutic level)

- Allergic reactions

- Patient’s ability to adhere to treatment

- Drug Intolerance

Furthermore, they can report the adverse drug reaction (ADR) to Yellow Card Centre Scotland. This system collects all reported adverse drug reactions and assesses whether a certain drug may negatively interact with others, if it doesn't agree with a certain population or if it may need to be recalled. The scheme aims to improve the safety of medication and it is the responsibility of doctors (working in hospital and primary care), pharmacists (working in hospital and the community), nurses, and HCPs (including physiotherapists) to report any adverse reactions. This can be done online, via an App or post.

HCPs in particular should be aware of a upside down black triangle on a medication packet. It means it is the first licensed use of the medication and may not have been exposed to a large number of patients. Therefore, are encouraged to report all suspected ADR which occur with medication with a black triangle regardless of the severity of the reaction.

It can be seen that the CSP guidelines for non-prescriber physiotherapists are slightly vague as they are dependent on an individual’s personal knowledge and level of experience. In a study by Braund and Abbott (2011) it was reported that a large number of non- prescriber musculoskeletal physiotherapists practice outwith their scope by recommending a dose or a brand of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to patients.

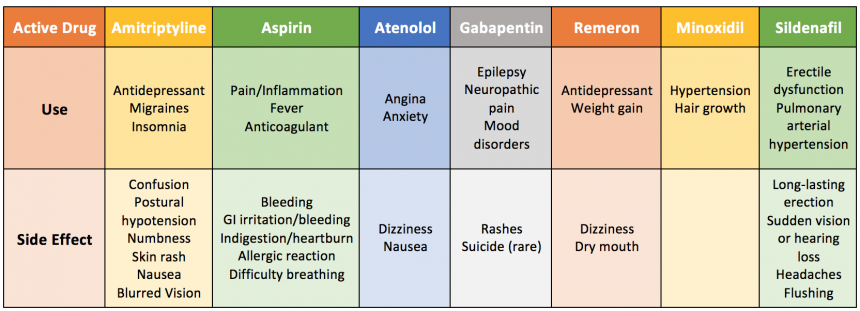

Furthermore, just over 70% were able to name side effects of NSAIDs as gastrointestinal upset, ulcers or bleeding, while only 30% were able to name respiratory, renal or allergic risks. NSAIDs in particular are one of the most common medications physiotherapists are asked questions about. It has been reported that physiotherapists feel pressured into answering questions regarding this medication, yet feel they are inadequate to do so. The evidence suggests physiotherapists should have a better understanding of their scope of practice. As well as having a greater knowledge of commonly prescribed medication, including side effects as shown in the tables below. Furthermore, with polypharmacy becoming more prevalent it is important for all HCP to be aware of drug interactions to pick up on potential or happening ADR.

How confident are you in your understanding of common prescriptions, side-effects and interaction?

Have a discussion with your physiotherapy or MDT team to consider everyone's perspective towards the role of physiotherapists within this scope of practice. Is it appropriate? Is it safe? Does using a holistic approach to deprescription dilute the safety and efficacy of current pharmaceutical practices?

Knowledge on Side effects and possible drug interactions[edit | edit source]

Table (1) illustrates a restricted list of the commonly prescribed medications physiotherapists may encounter with their patients and the side effects that can occur as a result. It is important that physiotherapists are aware of these, and other common medication, side effects to be able to identify these issues as they arise.

Table (1): Common medications encountered by physiotherapists and their common side effects

| Type of Medication | Purpose of Medication | Side-Effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Analgesia- reduce pain, inflammation | Dizziness, headache, renal impairment, gastrointestinal toxicity ulcers and/or bleeding and increased risk of cardiovascular side effects | High dose aspirin, celecoxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen, indometacin |

| Diuretics | High blood pressure (hypertension), fluid retention because of heart failure, fluid build up in the abdomen caused by liver damage | Dizziness, headaches, increased blood sugar, muscle cramps, nausea, increase frequency to urinate | Furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, Edecrin |

| Opioid analgesics | Moderate to severe pain | Constipation, drowsiness, confusion, delirium, nausea, dizziness | Codeine, tramadol morphine

Can combine with NSAIDs |

| Anticoagulants | High risk of blood clots- Atrial fibrillation, stroke, Myocardial infarction, DVT, pulmonary embolism. | Excessive bleeding, Dizziness, weakness, severe stomach and headache | Heparin, warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixabanm, edoxaban |

| Beta blockers | Hypertension, angina, some abnormal heart rhythms (e.g. AF), Myocardial infarction, glaucoma, overactive thyroid symptoms | Dizziness, weakness, drowsiness, fatigue, cold hands and feet, dry mouth, skin, or eyes, headache, upset stomach, constipation, blurred vision, slowed heart rate | Atenolol, bisoprolol, cardicor, carvedilol, metoprolol, nebivolol, propranolol |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | Hypertension, heart failure | Dizziness, headaches, cold or flu-like symptoms, muscle weakness/ cramps | Candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, valsartan, olmesartan |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE) | Heart failure, hypertension | Dry cough, headaches, dizziness, hyperkalemia, hypotension | Enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril |

Table (2) demonstrates a limited list of medications that are “multi-purposeful”, meaning they can target and treat more than one issue. It is important to be aware of these medications and not to assume the patient has been prescribed the medication for the most common reason. It is also valuable to be aware of these medications for if a patient has more than one complication, it may be possible to suggest prescription of 1 medication to treat both issues, rather than 2 medications with 2 possible lists of side effects.

Table (2): Examples of Repurposing Drugs

Table (3): Most Common Medications that result in falls

| Types of Medication | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hypnotics and Sedatives | Insomnia- induce sleep | zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone |

| Antidepressants | Treat depression, anxiety, PTSD, OCD | Fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, duloxetine, venlafaxine, amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine |

| Benzodiazepines | Severe anxiety, insomnia, seizures | Diazepam, lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, temazepam, nitrazepam, loprazolam, lormetazepam, clobazam |

Table (3) illustrates medications that are highly correlated with falls. If a patient is becoming greatly affected by this falls side effect and is subsequently jeopardizing their safety, cessation or alteration of dose may be proposed. As a non-prescriber, this can be discussed with the patient’s GP who has the authority to make such changes. Physiotherapy interventions can be suggested in conjunction with the medication alteration to target the falls risk, or as a substitute to the purpose of the medication.

The more medications a patient takes, the risk is increased of the drugs interacting with each other (Silvestrini Ref).

Other dependable factors increasing the probability of interactions are

- Genetics

- Age

- Lifestyle

- Other medical conditions

- Duration of medication

Drug interactions are not just limited to drug-drug interactions. Certain drugs can have negative interactions with food, beverages and supplements also. A well known example of this is alcohol.

As an independent prescriber, supplementary prescriber or non-prescriber physiotherapist, it is important to be aware of medications that can negative interactions with each other. Some patients may be on prescription medication and when feeling unwell visit their local pharmacy to purchase OTC medications, which unknowingly to them, may not be recommended in conjunction with their prescribed medication.

Here is an easy guide video on information regarding drug interactions:

If you have any queries regarding medications and their interactions or would like to learn more, you can input their drug names into the following “Drug Interaction Checkers”

https://reference.medscape.com/drug-interactionchecker

http://healthtools.aarp.org/drug-interactions/?intcmp=AE-HEA-DRUG-TERTNAV-DITERC

Click on the following link to see how much you've learned about common medications, ways in which drugs are repurposed, the presentation of adverse drug interactions and side effects!

https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/MBV538P

Common Populations at Risk[edit | edit source]

The use of multiple drugs is not always an indicator of poor drug treatment or overmedication (Tamminga 2011). Appropriate medication depends on whether or not the advantages outweigh the disadvantages which is subjective to both the individual and their given condition(s). It can be very hard to predict the side-effects or clinical effects of a drug combination without testing it on the specific individual as the effects all very based on the individual's genome-specific pharmocokinetics (Taminga 2011).

1. Elderly Populations[edit | edit source]

As a result of improvements in health care services and modern technology, the aging baby-boomer generation has a longer life-expectancy than previous generations. However, the risk of multiple chronic diseases increases with age requiring multiple medications. Various studies have shown that on average, older adults are consuming 2-9 medication per day with a shocking prevalence of inappropriate medication use of 11.5-62.5% (Hajjar et al. 2007; Kwan et al. 2014). Elderly populations are specifically at risk of adverse drug reactions (ADR) as a result of age related changes such as increased medication sensitivity, slower-metabolism and slower drug elimination. There appears to be a virtually linear relationship between the occurrence of ADRs with every drug taken as well as a cumulative potential for adverse side-effects (Viktil et al. 2007; Kwan et al. 2014). What is more concerning is the fact that signs of polypharmacy are often masked as usual signs and symptoms of aging including: tiredness, decreased alertness, constipation, diarrhea, incontinence, lack of appetite, confusion, depression or lack of interest in usual activities, weakness, visual or auditory hallucinations, anxiety, dizziness.

Polypharmacy in elderly populations can also lead to poor quality of life, increase the risk of falls and poor compliance with medication. The concept of a "pill burden" is recognized as having so many different drugs or pills to take on a regular basis that it can be challenging to organize, store, consume, let alone understand their purpose or appropriate regimes. In turn, "pill burden" increases the risk of hospitalization, medication errors, and has negative effects of healthcare outcomes and costs (Malhotra et al. 2001; Gomez et al. 2015).

Reconsidering this population's prescription on a regular basis is important to maximize their quality of life throughout their remaining years. The relief achieved from reducing their medication load may potentially lead to better outcomes. Special attention may also be needed towards those considered to have frailty, the clinically recognized state of increased vulnerability, as they are even less resistant to adversity and not considered as a separate entity in most clinical guidelines (Sergi et al. 2011).

2. Psychiatric Patients[edit | edit source]

Psychiatric disorders are complex our understanding of these conditions remains inadequate. Although the complexity of illnesses such as schizophrenia may understandably require a polypharmaceutical approach, Tamminga et al. (2011) believes "it is incumbent upon us to step forward and test these assumptions so that validated combination treatments are demonstrated to enhance therapeutic outcomes and not only ameliorate side effects." There is insufficient and conflicting evidence regarding the benefit or detriment of polypharmacy emphasizing its subjectivity and need for further research.

Polypharmacy may be recommended to treat adverse effects of the primary drug, the provide acute improvements while waiting for delayed effects of another prescription, to boost the effectiveness of a primary drug or to treat intervening illnesses such as depression during the course of their schizophrenia (Kukreja et al. 2013) however, due to the lack of research in the demerits of drug combinations and increased risk of adverse drug to drug interactions, special attention must be paid towards education, proper screening, and further research.

3. COPD and Multi morbidity[edit | edit source]

COPD places a significant burden on the health care system in the UK as it is the second most common pulmonary disease in the UK and is a prevalent condition in individuals with multimorbidity (Hanlon et al. 2018). Those affected by COPD are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with a range of cardiovascular comorbidities than those without (Hanlon et al. 2018). COPD is also found to be related to long term conditions such as obesity, depression, gasto-oesophageal, osteoporosis and lung cancer (Hanlon et al. 2018). Over half of COPD patients in the UK Biobank reported polypharmacy of more than 5 medications and 15% reported more than 10 medications as a result of co-existing conditions (Hanlon et al. 2018). Considering the increasing prevalence of co-morbidity around the world and more so with age, populations with COPD should be considered at risk of polypharmacy and potential over-prescription yet further guidelines to protect them against this risk are necessary.

Individuals with moderate to severe COPD with a high risk of exacerbation are recommended to use bronchodilators and inhales corticosteroids (ICS) in combination (White et al. 2013). Long and short acting bronchodilators as well as other therapies such as long-acting theophylline, acetylcysteine, azithromycin, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, and roflumilasts have been found to reduce exacerbations and improve quality of life in COPD populations however recent evidence highlights inaccuracies in prescription accuracy according to the publishes GOLD guidelines. In addition there appears to be a lack of understanding on which of the multiple medications patients should be taking to improve their clinical response which might further be complicated by other long-term conditions. Not only does this increase the risk of over-prescription but COPD taking ICS and bronchodilators over the long term are found to have increased the risk of pneumonia, and fractures (White et al. 2013; Grouse et al. 2014 Teichert et al. 2014; Gonzalez et al. 2017). Experimenting with the combination of these expensive medications can impose a financial burden on both the health care system and the individual (Grouse et al. 2014). Although this issue requires further research to develop clearly defined guidelines similar to treating patients with hypertension, COPD populations should be monitored for inappropriate medication combination, over-prescription and the relevant side effects (Grouse et al. 2014; Hanlon et al. 2018)

4. Other Conditions[edit | edit source]

- Recent hospitalizations/major surgery

- People seeing multiple doctors

- Terminally ill patients

Non-Pharmacological Interventions[edit | edit source]

Read through the latest issue of The King's Fund regarding the role of changes in the NHS. Reflect with yourself or your AHP team about how your current practice reflects these proposed changes and suggestions you may have on ways to improve the value of the NHS.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kingston A, Robinson L, Booth H, Knapp M, Jagger C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age and ageing 2018;For the MODEM project:1-7.

- ↑ Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, Lewis C, Fahey T, Smith S.M. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ 2015;350:1-6.

- ↑ Sönnichsen A, Trampisch U.S, Rieckert A, Piccoliori G, Vögele A, Flamm M, Johansson T, Esmail A, Reeves D, Löffler C, Höck J, Klaassen-mielke R, Trampisch H.J, Kunnamo I. Polypharmacy in chronic diseases– Reduction of Inappropriate Medication and Adverse drug events in older populations by electronic Decision Support (PRIMA-eDS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bushardt R.L, Massey E.B, Simpson T.W, Ariail J.C, Simpson K.N. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2008;3:383–389.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 McGrath K, Hajjar E.R, Kumar C, Hwang C, Salzman B. Deprescribing: A simple method for reducing polypharmacy. The Journal of Family Practice 2017;66:436-445

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Reznik J, Keren O, Morris J, Biran I. Pharmacology Handbook for Physiotherapists. Australia: Elsevier; 2016.

- ↑ NICE. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy. 2017 [online] [viewed 16/04/2018]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt18/chapter/evidence-context

- ↑ Banerjee, A, Mbamalu D, Ebrahimi S., Khan A.A, Chan, T.F. The prevalence of polypharmacy in elderly attenders to an emergency department – a problem with a need for an effective solution. International Journal of Emergency Medicine 2011;4.

- ↑ Junius-walker U, Theile G, Hummers-pradier E. Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among older primary care patients in Germany. Family Practice 2007;24.

- ↑ Sigurdardottir A.K, Arnadottir S.A, Gunnarsdottir E.D. Medication use among community-dwelling older Icelanders. Population-based study in urban and rural areas. Laeknabladid 2011;97:675–680.

- ↑ Slabaugh S.L, Maio V, Templin M, Abouzaid S. Prevalence and risk of polypharmacy among the elderly in an outpatient setting: a retrospective cohort study in the Emilia-Romagna region. Italy Drugs Aging 2010;27:1019–1028.

- ↑ Bourgeois F.T, Shannon M.W, Valim C, Mandl K.D. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2010;19:901-910.

- ↑ Nair N.P, Chalmers L, Peterson G.M, Bereznicki B.J, Castelino R.L, Bereznicki L.R. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions–the need for a prediction tool. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2016;11:497-506.

- ↑ Crenstil V, Ricks M.O, Xue Q.L, Fried L.P. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of community dwelling, disabled older women: factors associated with medication use. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacology 2010;8:215–224.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2010;20:514–522.

- ↑ Fletcher P.C, Berg K, Dalby D.M, Hirdes J.P. Risk factors for falling among community-based seniors. Journal of Patient Safety 2009;5:61–66.

- ↑ Espino D.V, Bazaldua O.V, Palmer R.F, Mouton C.P, Parchman M.L, Miles T.P, Markides K. Suboptimal medication use and mortality in an older adult community-based cohort: results from the Hispanic EPESE Study. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2006;61:170-175.

- ↑ Akazawa M., Imai H, Igarashi A, Tsutani, K. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacology 2010; 8:146-160

- ↑ Steinman M.A, Landefeld C.A, Rosenthal G.E, Berthenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli P.J. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2006;54:1516-1523

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Reeve E, Moriarty F, Nahas R, Turner J.P, O’Donnell L.K, Hilmer S.N. A narrative review of the safety concerns of deprescribing in older adults and strategies to mitigate potential harms. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2017.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Reeve E, Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: A narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. European Journal of Internal Medicine.2017;38:3-11.

- ↑ Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2013;66:201-202

- ↑ Woodward M.C. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2003;33:323–328.

- ↑ Iyer S, Naganathan V, Mclachlan A.J, Le Couteur D.G. Medication Withdrawal Trials in People Aged 65 Years and Older. A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 2008;25:1021-1031.

- ↑ Morin L, Laroche M.L, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2016;17:862

- ↑ Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I, Pearson, S.A, Lindsey L, Holmes H. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2017;7: 113–121.

- ↑ Page A.T, Etherton-beee C.D, Clifford R.M, Burrows S, Eames M, Potter L. Deprescribing in frail older people – Do doctors and pharmacists agree? Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2016;12:438-449

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Sirois C, Oullet N, Reeve E. Community-dwelling older people’s attitudes towards deprescribing in Canada. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2017;13:864-870.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Townsend C.O, Kerkvliet J.L, Bruce B.K, Rome J.D, Hooten W.M, Luedtke C.A, Hodgson J.E. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: Comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain 2008;140:177-189.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Huffman K.L, Sweis G.W, Gase A, Scheman J, Covington E.C. Opioid Use 12 Months Following Interdisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation with Weaning. Pain Medicine 2013;14:1908-1917.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hooten W.M, Townsend C.O, Sletten C.D, Bruce B.K, Rome J.D. Treatment Outcomes after Multidisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation with Analgesic Medication Withdrawal for Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pain Medicine 2007;8:8-16.

- ↑ Kahan M, Mailis-gagnon A, Wilson L, Srivastava A. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain Clinical summary for family physicians. Part 1: general population. Canadian Family Physician 2011;57:1257-1266.

- ↑ Berna C, Kulich R.J, Rathmell J.P. Tapering Long-term Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence and Recommendations for Everyday Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2015;90:828-842

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts M.S, Wiese M.D. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence based, patient-centred deprescribing process. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2014;78:738–747.

- ↑ Scott I.A, Hilmer S.N, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, Gnjidic D, Del Mar C.B, Roughead E.E, Page A, Jansen J, Martin J.H. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:827-834.

- ↑ Belcher V.N, Fried T.R, Agostini J.V, Tinetti M.E. Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2006;21:298–303.

- ↑ Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted R. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2005;20:531–535.

- ↑ Reeve E, Denig P, Hilmer S.N, Ter Meulen R. The ethics of deprescribing in older adults. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 2016;13:581-590

- ↑ Stacey D, Légaré F, Col N.F, Bennett C.L, Barry M.J, Eden K.B, Holmes-rovner M, Llewellyn-thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu J.H Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014;28

- ↑ Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts M.S. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1013–28

- ↑ Steinman M.A. Polypharmacy - time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Internal Medicine 2016;176:482–483.

- ↑ Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts M.S, Wiese M.D. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:793–807.

- ↑ Linsky A, Simon S.R, Bokhour B. Patient perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Patient Education and Counseling 2015;98:220–225.

- ↑ Reeve E, Low L.F, Hilmer S.N. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications. British Journal of General Practice 2016;66:552–60.

- ↑ Anderson K, Freeman C, Stowasser D, Scott, I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014;4.

- ↑ (Page et al. 2016)

![[46]Page et al. 2016](/images/thumb/8/84/Screen_Shot_2018-04-11_at_8.37.00_AM.png/557px-Screen_Shot_2018-04-11_at_8.37.00_AM.png)