Sternoclavicular Joint Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | ||

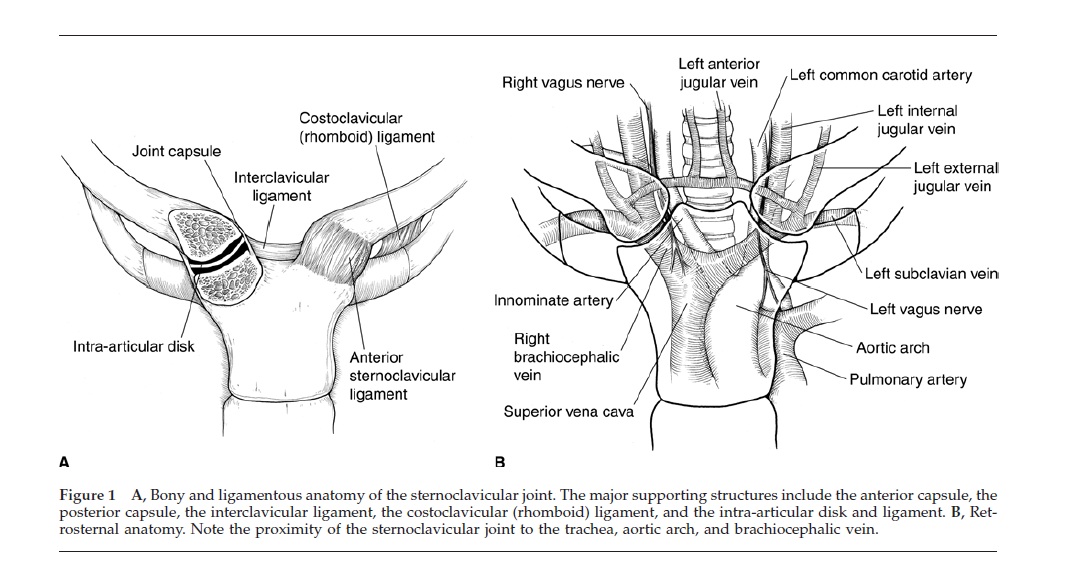

The Sternoclavicular (SC) joint is the only bony joint that connects the axial and appendicular skeletons. The SC joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation of the sternum and the clavicle. Due to the joint’s articulation between the medial clavicle and manubrium of the sternum and first costal cartilage, the joint has little bony stability. Between the medial clavicle and manubrium is a dense fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the joints into two distinct synovial compartments. The intra-articular ligament provides joint stability and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle. This ligament originates from the junction of the first rib and sternum and passes through the SC joint and attaches to the clavicle on the superior and posterior side. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments restrain anterior and posterior translation of the medial clavicle. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments originates on the anterior and posterior ends of the clavicle, respectively, and inserts onto the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium, respectively. The SC joint is supported superiorly by the interclavicular ligament that connects the superomedial portions of each clavicle. The blood supply to the SC joint is from the articular branches of the internal thoracic and suprascapular arteries. The SC joint is innervated by the branches of the medial suprascapular nerve. The brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein all lie directly posterior to the SC joint<ref name="Higginbotham">Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.</ref>.<br> | The Sternoclavicular (SC) joint is the only bony joint that connects the axial and appendicular skeletons. The SC joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation of the sternum and the clavicle. Due to the joint’s articulation between the medial clavicle and manubrium of the sternum and first costal cartilage, the joint has little bony stability. Between the medial clavicle and manubrium is a dense fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the joints into two distinct synovial compartments. The intra-articular ligament provides joint stability and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle. This ligament originates from the junction of the first rib and sternum and passes through the SC joint and attaches to the clavicle on the superior and posterior side. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments restrain anterior and posterior translation of the medial clavicle. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments originates on the anterior and posterior ends of the clavicle, respectively, and inserts onto the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium, respectively. The SC joint is supported superiorly by the interclavicular ligament that connects the superomedial portions of each clavicle. The blood supply to the SC joint is from the articular branches of the internal thoracic and suprascapular arteries. The SC joint is innervated by the branches of the medial suprascapular nerve. The brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein all lie directly posterior to the SC joint<ref name="Higginbotham">Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.</ref>.<br> | ||

[[Image:Scjointanatomy.jpg|Figure adapted from: Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.]] | |||

== Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process<br> == | == Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process<br> == | ||

Revision as of 00:14, 18 March 2011

Let me know if you need any assistance.Be the first to edit this page and have your name permanently included as the original editor, see the editing pages tutorial for help.

|

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page. Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more. |

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

The Sternoclavicular (SC) joint is the only bony joint that connects the axial and appendicular skeletons. The SC joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation of the sternum and the clavicle. Due to the joint’s articulation between the medial clavicle and manubrium of the sternum and first costal cartilage, the joint has little bony stability. Between the medial clavicle and manubrium is a dense fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the joints into two distinct synovial compartments. The intra-articular ligament provides joint stability and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle. This ligament originates from the junction of the first rib and sternum and passes through the SC joint and attaches to the clavicle on the superior and posterior side. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments restrain anterior and posterior translation of the medial clavicle. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments originates on the anterior and posterior ends of the clavicle, respectively, and inserts onto the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium, respectively. The SC joint is supported superiorly by the interclavicular ligament that connects the superomedial portions of each clavicle. The blood supply to the SC joint is from the articular branches of the internal thoracic and suprascapular arteries. The SC joint is innervated by the branches of the medial suprascapular nerve. The brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein all lie directly posterior to the SC joint[1].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

Patients with SC joint dysfunction can be classified into two categories based of the mechanism of injury: traumatic or atraumatic.

Traumatic

Traumatic injuries to the SC joint range from minor subluxation to complete dislocations. Injuries to the SC joint are rare and infrequently seen in physical therapy. Full dislocation of the SC joint is rare due to the large amount of force and specific vector required to displace the joint. Typically, traumatic injuries to the SC joint occur during: falls, sports-related injuries or vehicular accidents. Anterior SC joint dislocations are more common[2][3]. Posterior dislocations have serious clinical implications as the surrounding nerves and vessels may be compromised[4].

Atraumatic

The SC joint is vulnerable to the same disease processes than occur in joints such as degenerative arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, infections, and spontaneous subluxation of the joint. A thorough history is required to determine the presence of non-musculoskeletal disorders[1].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Traumatic

Patients usually present with complaints of pain and swelling. With mild sprains or subluxations, there may be complaints of instability in the joint. Often with dislocations, a palpable and observable step-off deformity at the SC joint may be present 1. Posterior dislocations may be associated with more significant symptoms such as: a feeling of compression of the trachea or esophagus, complaints of dyspnea, choking, difficulty swallowing, or a tight feeling in the throat. In the most severe cases of posterior dislocation, complete shock or a pneumothorax may occur and if left untreated and can be associated with complications such as thoracic outlet syndrome and vascular compromise[5].

Classification of Types of Injury[2][3]

- Type I injury is associated with mild to moderate pain associated with movement of the upper extremity. Instability is usually absent and the SC joint is tender to palpation and may be slightly swollen.

- Type II injury is associated with partial tears in the supporting ligaments. The joint may sublux when manually stressed but will not dislocate. Patients report more swelling and pain than those with Type I injuries.

- Type III injury results in complete dislocation, either anteriorly or posteriorly, of the SC joint. Patients report severe pain that is aggravated by any movement of the upper extremity. The involved shoulder may be protracted in comparison to the uninvolved side. Patients may also hold the affected arm across the chest in an adducted position and support the involved arm with the contralateral limb.

Atraumatic[1]

- Osteoarthritis (OA) of the SC joint includes: a report of pain and swelling at the SC joint that is aggravated with palpation, ipsilateral shoulder abduction, and/or shoulder flexion about the horizontal. Other findings include: osteophyte prominence at the medial end of the clavicle, creptius, or a fixed subluxation. Degenerative processes of the SC joint become increasingly more common with advanced age. Postmenopausal women are more susceptible than premenopausal women or men.

- Rheumatoid arthritis, RA, of the SC joint includes: a report of swelling of the SC joint, tenderness of the SC joint, crepitus, and painful limited movement of the shoulder. Other findings include synovial inflammation, pannus formation, bony erosion, and degeneration of the intra-articular disc. Isolated joint involvement is rare. It is more common to see multiple joints affected with RA and often is present bilaterally.

- Infection of the SC joint include: report of pain, swelling of the SC joint, tenderness around the SC joint, fever, chills, and/or night sweats. A definitive diagnosis is found with aspiration or open biopsy. Septic arthritis is associated with infection of the SC joint and is seen in patients that have RA, sepsis, infected subclavian central lines, alcoholism, or HIV. It is also seen in immunocompromised patients, renal dialysis patients, and intravenous drug users.

- Spontaneous anterior subluxation includes: patient report of a “pop”, or sudden subluxation of the medial end of the clavicle. It is commonly seen in patients in their teens and twenties who demonstrate ligamentous laxity and may occur with overhead elevation of the arm.

- The clinical presentation of seronegative sponyloarthropathies is similar to that of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, or colitic arthritis. This disorder is characterized by age of onset before 40 years old, inflammation of large peripheral joints, and absence of serum antibodies. Patients present with unilateral involvement, swelling, and tenderness of the SC joint, and pain with full arm abduction.

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis includes soft tissue ossification and hyperostosis, or excessive growth of bone, between the clavicles. A patient with sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis may report localized pain, swelling and warmth over the SC joint. Symptoms are often bilateral and the range of motion of the shoulder can be affected.

- Condensing osteitis includes: patient report of pain and swelling over the affected area. Symptoms are usually unilateral and present in women in their late child bearing years. This condition presents with sclerosis and enlargement of the medial end of the clavicle.

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis) includes: discomfort, welling, and crepitus of the SC joint in absence of trauma, infection, or other symptoms. The patient reports loss of ipsilateral shoulder range of motion.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Plain radiographs are indicated at the initial evaluation for SC joint disorders[1]. Computed Tomography (CT) scans are indicated for disease processes in which there is bony destruction or ossification. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides information of whether there is inflammation, soft tissue masses, or osteonecrosis are present. While a MRI radiograph is very thorough, CT is a preferable imaging modality in acute settings due to speed, availability and ability to discern between soft-tissue and bony injuries, especially in acute scenarios[5]. Laboratory studies may help rule in or rule out a certain diagnosis when inflammatory or infectious disease processes are suspected, such as RA, septic arthritis, or osteomyelitis.

Radiographic evaluation for SC joint dislocations includes standard antero-posterior (AP) radiographs of the chest that may suggest and injury to the SC joint[4]. This may, however, not be the best view for visualization of the joint. The use of the serendipity view radiograph has been shown to be of better diagnostic reliability since it is a bilateral view of the SC joint.

See figure below for algorithmic illustration of clinical decision making process with SC joint dysfunction.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are not any specific outcome measures that specifically look at the SC joint but the following could potentially used as SC joint injury outcome measures since SC joint injuries typically impact upper extremity function:

- DASH

- QuickDASH

- Penn Shoulder Score

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

The physical examination of a patient with a suspected SC joint injury may include the following:

- Screening of the cervical spine

- Active and passive range of motion of the associated shoulder region, AC, and SC joints

- Observation and palpation of key structures/regions

- Resistive testing of the shoulder region

- Functional testing

Little evidence exists for the optimal management of SC joint dysfunction, but may be impairment and patient-response driven. The physical therapist may consider exercises, manual therapy techniques, education or other treatment interventions based on the observed impairments. Often times, SC dysfunction does not require an extensive course of physical therapy.

Initial physical therapy interventions may include:

- Mobility exercises including AROM, AAROM, PROM of the shoulder

- Resistive strengthening

- Motor control training

- Scapular stabilization

- Manual therapy directed at the SC joint, GH joint, and AC joint

In severe, acute traumatic dislocations, reduction of the joint may be required by the appropriate medical provider. Posterior dislocations of the SC joint should be considered a medical emergency due to the proximity of major arteries, nerves, trachea, esophagus and lungs. Typically, Type I and II injuries are usually treated non-surgically, involving a short period of immobilization in a sling, oral NSAIDs, and ice[4]. After the period of immobilization, the patient can return to prior levels of activity gradually based on level of comfort. For type II injuries where the clavicle becomes displaced, the joint can be reduced by placing the patient in a figure-of-eight brace. Patients may receive physical therapy for graded rehab including exercises, education and/or manual therapy. Patients should be informed that there is likely to be a recurrence of instability and potentially a permanent deformity. Many patients will have full functional capacity despite an observable deformity of the SC joint. Operative treatment should only be considered in symptomatic patients in which conservative treatment has failed or for cosmetic reasons due to the permanent SC joint deformity.

Differential Diagnosis[1][4][6]

[edit | edit source]

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Septic arthritis

- Atraumatic subluxation

- Seronegative sponyloarthropathies

- Crystal deposition disease

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis

- Condensing osteitis

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis)

- SC/AC joint dysfunction

- Sternal Fracture

- Clavicular Fracture

- Anterior dislocation of the SC joint

- Posterior dislocation of the SC joint

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to key evidence with regards to any of the above headings

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wirth MA, Rockwood CA. Acute and chronic traumatic injuries of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1996;4:268-278.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bontempo N, Mazzocca A. Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2010;44:361-369.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Groh GI, Wirth MA. Management of traumatic sternoclavicular joint injuries. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. January 2011;19(1):1-7.

- ↑ Gaunt BW, Boers, T. SC, AC, & spinal specific manual techniques can dramatically increase shoulder girdle elevation. Presented at: Combined Sections Meeting; Feb 10, 2011; New Orleans, LA.