Spondylolysis in Young Athletes: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

[[Image:Weightlifter .jpg|center|Figure 3: Weightlifter in lunge position post jump]]<br> | [[Image:Weightlifter .jpg|center|Figure 3: Weightlifter in lunge position post jump]]<br> | ||

= Treatment | = Treatment<br> = | ||

== Conservative == | == Conservative == | ||

| Line 90: | Line 88: | ||

The use of specific core strengthening exercises with spondylolysis patients has been shown to significantly reduce pain and enhance functional ability when compared to other conservative treatments (O’Sullivan, 1997).<br> | The use of specific core strengthening exercises with spondylolysis patients has been shown to significantly reduce pain and enhance functional ability when compared to other conservative treatments (O’Sullivan, 1997).<br> | ||

== Surgical == | |||

= Patient Experience = | = Patient Experience = | ||

Revision as of 14:12, 15 January 2015

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Further adding to the knowledge of the Spondylolsis physiopedia page, this Wiki page aims to provide readers with a background understanding of spondylolysis, why the young athletic population are more at risk and give an insight into the different management options which are available. We will discuss in detail the different treatment options using pre-existing evidence, with a main focus on the efficacy of each treatment option in returning the athlete to sport.

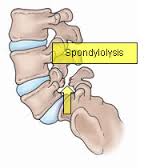

What is Spondylolysis?[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis is defined as a bony defect within the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch (Syrmou, 2010. It presents as a weakness or fracture at this point (syrmou, 2010). The vast majority of spondylolitic defects are seen at level L5 (85-95%) (Standaert, 2003), with level L4 being the second most likely to be affected. The higher levels of the lumbar spine are rarely affected (Standaert, 2003).

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that spondylolysis is present in 6 – 8% of the general population (Leone). The incidence has seen to be increased (47%) within the young athletic population (micheli). There is a particular increased risk in sports which subject athletes to repetitive hyperextension and rotation across the lumbar spine (iwanoto). Gymnasts, in particular, have been found to be 4 times more likely than their non athletic peers to develop a spondylolysis (Jackson). Research has also found there to be an increased risk for cricket bowlers, particularly fast bowlers (hardcastle).

The exact cause of spondylolysis currently remains unclear, with many factors thought to contribute to its development (McCleary, 2007). It has been described as hereditary, or acquired as a result of repetitive stress to the lumbar spine (Haun, 2005). In the young athlete the spine is still growing, giving rise to numerous ossification centres which leave points of weakness in the spine (McCleary, 2007). This leaves young athletes, in particular those exposed to repetitive hyperextension and rotation of the lumbar spine (Iwanoto), susceptible to injury and the development of spondylolysis.

Clinical Presentation

[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis in Sport[edit | edit source]

It was reported that 47% of low back pain in young athletes is diagnosed as spondylolysis (Micheli & Wood, 1995; McCleary & Congeni, 2007). High incidence rates of spondylolysis have been reported in a number of sports including cricket, gymnastics, tennis and weightlifting. Therefore this section will briefly touch upon some of these sports and why these young athletes are more predisposed to this condition.

Cricket[edit | edit source]

A 2002 study (Gregory, Batt, Wallace) observed bowlers over 6 months; they found that 10% of spin bowlers and 12% of fast bowlers developed LBP over the season. The action of bowling in cricket involves rotation and side flexion of the spine at high speeds. During the delivery phase the bowler is performing these movements to the best of their ability in order to gain as much speed, spin and strength to the ball. As the front leg comes forward to deliver the ball, forces travelling through the leg and up into the lumbar spine can be 3-9 times that of our bodyweight. Adding to this that the bowler will have to bowl 6 balls every over for as many as 9-10 overs. It is not hard to see why this repetitive and powerful motion may lead to a spondylolysis.

Studies believe that young cricketers are more at risk due to longer and more intense training sessions, poor preparation and technique, longer spells of bowling and subsequently overuse

It is common for these athletes to report non-specific low back pain, which often feels like a dull ache but can become a sharper pain during their sporting activity.

Treatment for this population can be difficult as it often involves rest in the early stages, this can be as long as 8 months in some cases. However it is then important to address factors such as muscle imbalance, core stability, flexibility and pelvic control. Although they will be unable to bowl during this period of time they can continue to maintain cardiovascular fitness – such as swimming and cycling – as long as they are symptom free. Most importantly treatment must be sport specific especially in the later stages of rehab.

Example: When focusing on core stability the player is standing on leg balancing on a soft cushion or trampette while performing the bowling action. This is later progressed by attaching the ball to a theraband, which is tied to a fixed point behind the player.

(Some of the information above was taken from a 2006 article in the Sport Ex magazine).

Gymnastics[edit | edit source]

It was reported in a paper published in 2000 (Guillodo, Botton, Saraux et al) that the incidence rate in gymnasts was between 15-20%, this is much higher than the general population. Once again it is not hard to understand why this would be due to the high physical demands of the sport, the hours of daily training and repetitive forces (Kruse & Brooke, 2009).

One case study that focused on female gymnasts in 1979 (Jackson, Wiltse, Circincione) looked at 100 gymnasts and found that 11 had spondylolysis and 6 of these had progressed to a spondylolysthesis. The girls described the pain as chronic, dull aching and found it was particularly aggravated when hyperextended.

Weightlifting[edit | edit source]

This is another high intensity sport, which involves increased forces. The incidence rate has been reported to be between 30.7-44% (Kotani, Ichikawa, Wakabayashi et al, 1970; Stone, Fry, Ritchie et al 1994). Studies believe there is a clear relationship between this condition and the stress of lifting.

Stone et al (1994) described the actions involved in weightlifting and discussed the excessive impact forces seen during the catching phase of the bar. They also noted that these stress and shear forces are greatly increased through the joints when the athlete completes the jump onto one leg.

Treatment

[edit | edit source]

Conservative[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment is generally the initial management plan for young athletes with spondylolysis. The most common form conservative management applied is physiotherapy and can consist of:

• Periods of rest/ activity modification

• Lumbosacral brace

• Core stability strengthening

• Electrical modalities

Physiotherapy with these patients aims to restore range of motion, stabilise and strengthen the spine, and to reduce pain (Hall & Brody, 1999).

The use and effectiveness of lumbosacral braces is still debated within the literature. Use of a brace is supposed to allow the healing of the bony defect in the pars interarticularis, reducing the athlete’s pain and allowing a return to sport. However, Watkins (2010) states that it is yet to be demonstrated statistically to enhance the healing of a spondylolitic defect. Previous studies though have found the use of bracing to be effective in allowing the return to sport for an athlete (Iwamoto, 2004; Sys, 2001). Both thes studies though, did include a period of exercise therapy following the use of the brace, prior to a return to sport.

Common physical therapy used in the rehabilitation of spondylolysis in young athletes is concentrated strengthening of the core stability muscles; transverse abdominus, multifidus and quadrates lumborum. With the main focus in the rehabilitation of athletes being a return to sport, it is important that core stability strengthening is progressed into functional, specific exercises for each athlete following an initial period of retraining/activating the core muscles.

The use of specific core strengthening exercises with spondylolysis patients has been shown to significantly reduce pain and enhance functional ability when compared to other conservative treatments (O’Sullivan, 1997).

Surgical[edit | edit source]

Patient Experience [edit | edit source]

Case Study from Clinical Practice [edit | edit source]

This account was taken from a physiotherapist working in an outpatients setting. The case study describes a past patient that she assessed and treated.

A 15 year old keen cricketer and golfer presented with acute right-sided low back pain which had come on suddenly after playing cricket at the weekend; at the time he was unable to run and in fact felt considerable pain walking. During the week before this he had been on a golfing holiday playing a round a day and on some days 2 rounds. He had experienced a dull pain three weeks before and it was always related to cricket. In fact, this young boy recalled some twinges of pain in the previous school term while playing in the nets. He was a fast bowler.

This boy was in good health with no previous episodes of back pain. He had recently had a growth spurt.

On examination there was significant right-sided muscle spasm on lumber movements. There was pain during flexion and right side flexion with an excessive amount of movement available. Right hip flexion was painful and a right straight leg raise resulted in low back pain. On palpation there was pain and resistance at L4/5 and L5/S1.

During the initial treatment manual therapy was used to settle the acute pain and spasm. The patient reported that this eased the pain until he then went and picked up cricket balls from off the floor. He was referred on for further investigations at this point.

An x-ray, including oblique views, showed evidence of a spondylolysthesis of L5/S1. Therefore An MRI was arranged. This clearly showed a bilateral pars interarticularis defect. However there was no forward displacement of L5.

The patient was then instructed to completely rest for the next four months, he was referred back for physiotherapy at this point. Now, on examination, his movements were pain-free. On palpation there was some mild stiffness in the low lumbar spine but the hip and straight leg raise showed no symptoms. Treatment at this point included gentle stability and strengthening exercises.

For example he was encouraged to stretch his hamstrings, use breathing control and begin lower transverse abdominal exercises: spine curls in lying, bridging exercises and stability exercises whilst moving the legs.

These were later progressed onto the Swiss Ball combined with more functional exercises in standing aiming towards cricket related exercises. For example using the overhead movement of the arm taking care not to over extend the lumbar spine. Ensuring there wasn't a hinge point into lumber extension and that rotation was used. It was also worth checking he had enough available shoulder movement.

Patient Testimonial [edit | edit source]

Kamal is a 21 year old, cricket player, playing at a competitive University level. He was diagnosed with Spondylolysis 5 years ago. and was treated conservatively with physiotherapy. In his testimony, made by ourselves, Kamal talks about his experiences, treatment, and emotional well being, as young athele with spondylolsis.