Snowboarder's Ankle

Original Editor - Puja Gaikwad

Top Contributors - Puja Gaikwad and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

In recent times snowboarding has increased in popularity dramatically, with this increase in popularity comes an increase in a distinct ankle injury which has been aptly termed ‘snowboarder’s ankle’. Snowboarding is a popular winter sport that includes riding a single board down a ski slope or on a half-pipe snow ramp. Snowboarder's Ankle is the common term for a fracture of the lateral process of the Talus (LPTF), often overlooked initially and misdiagnosed as a severe ankle sprain.[1] The term snowboarder’s ankle comes from this fracture being 15x more likely amongst snowboarding associated ankle injuries than any other ankle injuries. Ankles are involved in 12-17% of snowboarding-related injuries.[2] A fracture to the lateral process of the talus in snowboarders can account for one-third of ankle fractures in this population. Various types of snowboard equipment, rider stance, and snowboarding activity tend to result in several types of injury. Soft boots give the snowboarder nearly twice the risk of ankle injury compared with hard boots.[3] Sideways motion, soft (non-hard shell) boots, and being strapped to the board are all factors that influence the higher rate.[4]

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The talus is one of seven articulating foot bones that are situated between the tibia and fibula of the lower leg and the metatarsal bones of the midfoot. The talus constitutes the lower part of the ankle joint and articulates with the medial malleolus of the tibia and the lateral malleolus of the fibula. The ankle joint permits dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. The underneath aspect of the talus articulates with the calcaneus forming a subtalar joint.[5] This joint enables inversion and eversion of the foot. The talus also articulates navicular bone allowing for subtle movements of the midfoot that play a vital role when walking on uneven ground. The lateral process of the talus is a wedge-shaped projection of the talar body. The top of the lateral process articulates with the fibula and makes a part of the lateral gutter of the ankle joint. The bottom of the lateral process forms the anterior part of the posterior subtalar joint. As the lateral process is involved in both the ankle and subtalar joints, it is significant in almost all foot movements.[6]

Mechanism of Injury[edit | edit source]

The mechanism of injury is likely that the injured ankle was the leading foot at the time of the fall. Recent research indicates that forced ankle joint dorsiflexion, eversion, and external rotation of the tibia causes the lateral process of talus (LPT) to shear away as it compresses against the calcaneus.[7] Dorsiflexion causes the Talus to become locked in place by the surrounding bones, the ankle roll outwards then causes that specific small area (LPT) to be compressed in between the calcaneus and the lateral malleolus of the fibula with sufficient force applied, the Talus will fracture, causing Snowboarder’s Ankle. It can occur during a landing from an aerial maneuver or a jump, especially when the landing has been over-rotated.[8][4]

Causes[edit | edit source]

The cause of the prevalence of the fracture of the Talus bone in snowboarders continues to be debated. In all likelihood, the probable cause is the convergence of both the biomechanics and equipment required for the sport. There is the unnatural sideways biomechanical motion of snowboarding. This is coupled with boots that are strapped to the board, which offer no prompt release upon falling. And then there are the boots which are different from the rigid boots worn in downhill skiing. Snowboarders’ boots are softer and suppler, providing for those thrilling jumps and amazing acrobatics. The more flexible construction of snowboarding boots also indicates that they are less protective on those hard landings from high up causing higher rates of foot and ankle injuries, including snowboarder’s ankle. Whenever there is sufficient force to break a bone, there is possible damage to ligaments and tendons as well.

Classification[edit | edit source]

According to Hawkins classification,

- Simple fractures (Type I): extending from the talofibular articular surface to the posterior talocalcaneal articular surface of the subtalar joint.

- Comminuted fractures (Type II): involving both the articular surfaces and the entire lateral process.

- Chip fractures (Type III): arising from the anterior and inferior portion of the posterior articular process involving only the subtalar joint and not extending into the talofibular articulation.[9]

Boack described a modified classification system that can be used to diagnose a fracture of the lateral process of the tibia. This classification covers four types of fracture, each type subdivided depending on the severity of the bony injury, degree of the Chondral lesion, and ligamentous stability. Based on their description, lateral process fractures are divided into four types.

Type 1: A small chip or avulsion fracture (< 0.5 cm):

1a - Small (extra-articular) fragment of the lateral process of the talus;

1b - Small fragment of the isolated medial tubercle of the posterior process of talus;

1c - Small (intra-articular) fragment of the lateral process of the talus.

Type 2: An intermediate fragment (0.5-1.0 cm) with some form of displacement:

2a - Extends into the subtalar joint without the involvement of the talofibular joint;

2b - Isolated fracture of the complete lateral tubercle of posterior process.

Type 3: A large fracture fragment (> 1 cm) with associated damage to the ankle as well as the subtalar joints:

3a - Single large fragment of the lateral process extending from the talofibular articular surface to the posterior facet of the subtalar joint;

3b - Comminuted fracture of the complete lateral process;

3c - Fracture of the whole posterior process of the talus.

Type 4: A severe form of fracture of either of the processes along with associated instability or dislocation of the subtalar joint.[10]

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

A snowboarder’s ankle has a similar presentation to that of a badly sprained ankle which is why it is important to monitor symptoms if an ankle injury occurs on the slopes. A history of an ankle sprain while snowboarding when the foot and ankle are fixed in stiff boots and strapped to the board whilst twisting the ankles to change direction should certainly arouse suspicion. A huge 33-41% of these injuries are reported to be missed on initial inspection and just diagnosed as a bad sprain as X-rays in this area are often hard to distinguish. [11]

Symptoms of this injury may include:

- Extreme tenderness and sensitivity to pressure around the back of the ankle. Tenderness is localized to a region about 1cm inferior to the tip of the lateral malleolus. Although often mimicking a lateral ankle sprain it may be difficult to specifically elicit this site.

- Swelling to the area.

- Ecchymosis

- There is normally difficulty in walking and an inability to bear weight.

The warning signs for a snowboarder's ankle injury involves inflammation and chronic pain. Those who sprained their ankles many times before and complain about persistent pain and swelling are also possible candidates for this specific type of ankle injury.[11]

Investigations[edit | edit source]

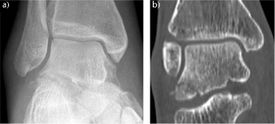

It may be possible to identify the fracture on a plain x-ray, but the fracture line is often quite subtle and difficult to see due to overlapping bony structures.[12] Both lateral (ankle at 90°) and ankle mortice views are recommended for a routine investigation. Ultrasound can be useful for the detection of cortical disruption and ankle joint space effusion; However, follow-up CT or MRI is often used to visualize the fracture line more clearly and provide information to thoroughly understand the extent of the injury. A CT scan should be considered when these symptoms occur for a long period of time because the scan will provide accurate detail if there is a suspected fracture.[13] The sequelae of missed fractures result in malunion, nonunion, long-term disability, and degenerative arthritis of the subtalar joint.[13][9]

Complications[edit | edit source]

A. Potential complications of surgery include general complications like:

- Infection

- Wound healing problem

- Nerve (sural nerve) damage

- DVT

- Pulmonary embolism

B. Complications that are particular to surgery for a lateral talus process comprise:

- Painful hardware. Occasionally, hardware like screws that were used to stabilize the fracture will require removal at a later stage.

- Nonunion. Sometimes the fracture fragments will fail to heal and may need to be removed.

- Arthritis of the Ankle or Subtalar joint. These joints are affected by this injury and can develop arthritis secondary to injury later on. It should be noted that with non-operative treatment, there is also the potential that arthritis involving the outside of the ankle joint or the subtalar joint can develop.[14]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Noble J, Royle SG. Fracture of the lateral process of the talus: computed tomographic scan diagnosis. British journal of sports medicine. 1992 Dec 1;26(4):245-6.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick DP et al. The snowboarder's foot and ankle. Am J Sports Med 1998; 26:271-7

- ↑ Mahmood B, Duggal N. Lower extremity injuries in snowboarders. Am J Orthop. 2014 Nov;43:502-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wijdicks CA, Rosenbach BS, Flanagan TR, Bower GE, Newman KE, Clanton TO, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF, Hackett TR. Injuries in elite and recreational snowboarders. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Jan 1;48(1):11-7.

- ↑ Lee C, Brodke D, Perdue Jr PW, Patel T. Talus Fractures: Evaluation and Treatment. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2020 Oct 15;28(20):e878-87.

- ↑ Sullivan MP, Firoozabadi R. Fractures of the Lateral Process of the Talus. Fractures and Dislocations of the Talus and Calcaneus. 2020:97-106.

- ↑ Funk JR, Srinivasan SC, Crandall JR. Snowboarder's talus fractures experimentally produced by eversion and dorsiflexion. The American journal of sports medicine. 2003 Nov;31(6):921-8.

- ↑ Boon AJ, Smith J, Zobitz ME, Amrami KM. Snowboarder's talus fracture: Mechanism of injury. The American journal of sports medicine. 2001 May;29(3):333-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Majeed H, McBride DJ. Talar process fractures: an overview and update of the literature. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Mar;3(3):85-92.

- ↑ Boack DH, Manegold S. Peripheral talar fractures. Injury. 2004 Sep 1;35:SB23-35.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kramer IF, Brouwers L, Brink PR, Poeze M. Snowboarders’ ankle. Case Reports. 2014 Oct 29;2014:bcr2014204220.

- ↑ Paul CC, Janes PC. The snowboarder's talus fracture. InSkiing Trauma and Safety: Tenth Volume 1996 Jan. ASTM International.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Von Knoch F, Reckord U, Von Knoch M, Sommer C. Fracture of the lateral process of the talus in snowboarders. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2007 Jun;89(6):772-7.

- ↑ da Fonseca LF, Pontin PA, Magliocca GD, Arliani GG, Roney A, de Cesar Netto C, Bastías GF, Chaparro F, Zhu Y, Xu X, Ramirez C. An International Perspective on the Foot and Ankle in Sports. Baxter's The Foot and Ankle in Sport. 2020 Jan 25:454.