Sleep Apnea: Difference between revisions

Irena Tran (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Irena Tran (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

Other diagnoses, especially other sleep disorders, may present as OSA due to similar symptoms (ex: fatigue, excessive sleepiness, HTN, sleep disturbance).<ref name="diagonse3">Culpepper L, Roth T. Recognizing and managing obstructive sleep apnea in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 11(6): 330-338. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805569/ (accessed 9 April 2016).</ref> | Other diagnoses, especially other sleep disorders, may present as OSA due to similar symptoms (ex: fatigue, excessive sleepiness, HTN, sleep disturbance).<ref name="diagonse3">Culpepper L, Roth T. Recognizing and managing obstructive sleep apnea in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 11(6): 330-338. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805569/ (accessed 9 April 2016).</ref> Alternative diagonses include: | ||

*Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy<ref name="epilepsy">Cho J, Kim D, Noh K, Kim S, Lee J, Kim J. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy presenting as obstructive type sleep apnea. J Epilepsy Res 2011; 1(2): 74-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3952334/ (accessed 8 April 2016)</ref> | *Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy<ref name="epilepsy">Cho J, Kim D, Noh K, Kim S, Lee J, Kim J. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy presenting as obstructive type sleep apnea. J Epilepsy Res 2011; 1(2): 74-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3952334/ (accessed 8 April 2016)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:44, 10 April 2016

Original Editors - Ylice Bridges and Irena Tran

Top Contributors - Irena Tran, Ylice Bridges, Lucinda hampton, Venugopal Pawar, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, WikiSysop, Adam Vallely Farrell and Lilian Ashraf

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sleep apnea is a disorder in which breathing is interrupted or paused during sleep. The pauses in breathing can last a few seconds to minutes and are long enough to:

• disrupt sleep

• decrease level of oxygen in the blood

• increase level of carbon dioxide in the blood

These breathing interruptions can occur more than 30 times an hour and significantly impair the quality of sleep. Because of this, sleep apnea is a leading cause of excessive daytime sleepiness.[1]

There are three types of sleep apnea: central, obstructive and mixed. Obstructive sleep apnea is the most common and the main focus of this article.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is caused by repeated partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway that diminishes or stops breathing.

Central sleep apnea occurs when the brain is less sensitive to changes in carbon dioxide levels in the blood and fails to send signals to the respiratory muscles to breathe deeper.

Mixed sleep apnea is a combination of both obstructive and central sleep apnea episodes.[1]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

OSA appears to be more prevalent (2.5x increase) in the African-American population than the Caucasian population.[2] [3] On the other hand, OSA was more prevalent in American Indians, Hispanic adults, and Pacific Islanders when obesity played a large role.[3] Population-based studies have also shown that men have a 2-3x increased risk of developing OSA than women, and a women's risk of OSA increases during pregnancy.[2] [3] OSA can occur in childhood and adolescence, but is more common at middle-age (40-60 years old).[2] After the age of 65, the occurrence of OSA plateaus, and this may be due to an "increase in mortality rate from OSA or a remission of OSA with aging."[2](p1221) Genetics increase the likelihood of developing OSA and in the craniofacial morphology and its conditions that may contribute to OSA.[3] Individuals with first-degree relatives who have OSA are 1.5-2 times more likely to have OSA.[3] OSA is also common in individuals who spend long periods of time sitting and driving, such as commercial trunk drivers.[4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Associated Co-morbidities

[edit | edit source]

- Hypertension (HTN) *Treatment of OSA has been shown to help decrease HTN, specifically in middle-aged individuals.[6]

- Obesity *Excessive body weight affects breathing capability due to increased adipose around the airway structures.[2] [3]

- Congested Heart Failure (CHF)[4]

- Fatal and Nonfatal Cardiovascular Events[7]

- Type II Diabetes[4]

- Pulmonary Hypertension[4]

- Stroke *OSA may be present prior to CVA as suggested in studies where neurological deficits, excluding OSA, recovered[4] [7]

- Depression[8]

- Cancer *especially breast, nasal, and prostate CA[9]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Numerous studies have shown that the use of pharmacological interventions in the treatment and management of OSA have not been as effective as the use of PAP, specifically CPAP.[4] [10] [11] As discussed further below, CPAP is currently the gold standard in the treatment of OSA. 8 It has been shown that some drugs, such as Phentermine with extended release Topiramate (Qsymia), used for weight loss was able to decrease weight as well as AHI (Apnea Hypopnea Index).[10] However, more studies will have to be conducted to better correspond the use of these weight loss drugs and the improvement of OSA.

Drugs promoting wakefulness have also been studied as an adjunct therapy to help relieve the symptoms of daytime sleepiness of OSA.[10]Particularly, Modafinil had been studied with results of increased daily functioning, but if it were used by itself, individuals would eventually succumb to the long-term effects of OSA since Modafinil only treats the symptoms.[10] Recently in Europe, Modafinil was no longer available for those with OSA indications due to fear of abuse and lack of knowledge to the extent of its benefits.[10] Additionally, the long-term risks of cardiovascular effects from Modafinil are still unclear, so further research is required in its benefits versus cons.[11]

Leukotriene Antagonists may be useful as adjunctive management.[11] A study noted a reduction in RDI (Respiratory Disturbance Index) and in adenoid size in children with OSA, but more research is required to substantiate its role as an intervention.[11] Donepezil has also been studied in treatment of OSA in Alzheimer's patients with the following positive outcomes: decrease AHI, improved REM sleep, and improved oxygen saturation.[11] Additionally, Mirtazapine was shown to decrease upper airway collapse, but may cause weight gain and sedation.[11]

Inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to decrease AHI and nasal airway resistance, improving daytime wakefulness.[11] However, studies did not indicate improved breathing during sleep to normal, so it is not recommended as a treatment option at this time.[11]

Finally, certain medications have been found to worsen OSA, and should not be prescribed to individuals with OSA. This includes CNS depressants (ex: opiates, benzodiazepines, barbiturates), certain Beta Blockers (ex: Propranolol), and some erectile dysfunction medications (ex: Sildenafil).[11]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Individuals suspected of OSA undergo a pretest assessment: a history, a clinical examination, and sleep questionnaires.[12]

- History: possible risk factors, co-morbidities, snoring, and what a normal night of sleep is like to him/her.[13]

- Indices: AHI (apnea-hypopnea index), RDI (respiratory disturbance index)[14]

- Clinical Examination: nose, tonsils, palate, tongue, neck circumference, upper airways.[13] [8] Findings are predominantly inconclusive and requires training for proper assessment.[13]

- Questionnaires: Epworth Sleepiness Score (ESS) for daytime sleepiness; Berlin questionnaire for common OSA risk factors and symptoms.[13]

- Oximetry: analyze oxygen saturation of hemoglobin to help identify individuals unlikely to have OSA.[8]

For the diagnosis of sleep disorders, including OSA, the standard test is Level 1 polysomnograptohy.[12] Individual spends the night in asleep laboratory, where a sleep technician is present, and 7 to 16+ channels are monitored.[12] These channels track the cardiovascular system, respiratory system, and neurologic system.[12] It can also monitor sleep duration, sleep arousals, and sleep stages.[12]

For those with a high probability of moderate to severe OSA, a good diagnostic test is Level 3 portable device (polygraph).[12] Portable monitors are brought into the individual’s home or preferred location.[12] These monitors look at at least 3 channels: oximetry, airflow, and respiratory effort in sleep.[12] It does not record sleep duration, arousals, sleep stages, or non respiratory sleep disorders.[12] Testing via these methods are most accurate when performed by an expert in sleep medicine.[13]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

add text here

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

A variety of methods are utilized to treat individuals with OSA:

- Weight reduction (diet, exercise, medications)[4] [11]

- Sleep positioning (avoid supine with positional devices)[4]

- Pharmacological treatments (topical nasal corticosteroids as an adjunct, refer to Medications for more information)[4]

- Oral applicances (Dental applicances)[4]

- Upper air reconstructive or bypass surgeries[4]

Oral Appliances

- Mandibular repositioning appliances (MRA) to hold the mandible in an advanced position[4]

- tongue retaining devices (TRD) to hold the tongue forward[4]

These attempt to avoid blockage of the upper airways while sleeping, and are commonly used with mild to moderate OSA and for those who do not benefit from CPAP.[4]

Positive airway pressure (PAP)

PAP, especially CPAP, is the most common method of treatment for mild, moderate, and severe OSA.[4] PAP provides pneumatic splintingto maintain the opening of the upper airway and effectively decreases AHI (Apnea Hypopnea Index= number of apnea or hypopnea episodesper hour of sleep).[4] [10] Normal AHI is less than 5 per hour.[10] PAP can be provided in several ways: continuous (CPAP, the gold standard), bilevel (BPAP), and autotitrating (APAP) and via three interfaces: nasal, oral, or nasoral.[4]

Surgical Interventions

These try to improve the airway passages via nasal, oral, oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, laryngeal, and global airways.[4]They are beneficial for those with severely obstructive anatomy and unsuccessful treatments with CPAPs or OAs.[4] These methods have shown varying degrees of success, so there is no consistent best treatment plan for all, but the combination of several of these therapies have proved to be effective.[4]

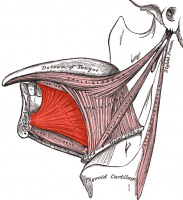

Hypoglossal Nerve-Stimulating System (HGNS)

This new treatment option, the insertion of the Hypoglossal Nerve-Stimulating System (HGNS), is currently being studied.[15] The Hypoglossal Nerve is the cranial nerve that innervates the tongue, especially the genioglossus muscle, and it plays a large role in maintaining airway patency.[15] Specifically, the genioglossus "protrudes the tongue, dilates the pharynx, and mitigates airflow obstruction during sleep."[15](p337)

This method has been studied via submental transcutaneous stimulation, direct fine wire stimulation, and direct hypoglossal stimulation.[15]

- Submental transcutaneous stimulation: aroused patients from sleep without clear improvements in the "airflow dynamics," but may increase lingual muscle tone and improve airway patency.[15](p338)

- Direct fine wire stimulation: produced effective contractions of the genioglossus to improve pharyngeal patency.[15]

- Direct hypoglossal stimulation: implantation of "hypoglossal cuff electrodes" around the proximal and distal nerve trunk can increase pharyngeal patency and decrease pharyngeal collapsibility without arousing the patients.[15](p338) There are currently "efforts to develop a fully implantable therapeutic HGNS system."[15](p338)

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Other diagnoses, especially other sleep disorders, may present as OSA due to similar symptoms (ex: fatigue, excessive sleepiness, HTN, sleep disturbance).[16] Alternative diagonses include:

- Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy[17]

- REM Behaviour Disorder[10]

- Periodic Limb Movement Disorder[10] [14]

- Central Sleep Apnea[10] [14]

- Insomnia[8]

- Aging and Age-Related Changes (sleeping less, tiredness, nocturia)[8]

- Medications (side effects, multiple prescriptions)[8]

- Hypothyroidism[8] [14]

- Narcolepsy[18] [14]

- Shift Work Sleep Disorder (SWSD)[18]

- Idiopathic hypersomnia[18]

- Asthma[14]

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)[14]

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmmonary Disease (COPD)[14]

- Depression[8] [14]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

1. Daoulah A, Ocheltree S, Al-Faifi S, Ahmed W, Asrar F, Lotfi A. Sleep apnea and severe bradyarrhythmia – an alternative treatment option: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2015; 9(1): 113-117.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4437673/ (OSA and Bradyarrhythmia)

2. Guimarães T, Colen S, Cunali P, Rossi R, Dal-Fabbro C, Ferraz O, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with mandibular advancement appliance over prostheses: A case report. Sleep Science 2015;8(2):103-106.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4608885/ (Treatment of OSA with Mandibular Appliance)

3. Fang H, Miao N, Chen C, Sithole T, Chung M. Risk of Cancer in Patients with Insomnia, Parasomnia, and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Nationwide Nested Case-Control Study. J Cancer 2015;6(11):1140-1147.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4615350/ (OSA and Cancer)

4. Cadby G, McArdle N, Briffa T, Hillman D, Simpson L, Knuiman M, et al. Severity of OSA Is an Independent Predictor of Incident Atrial Fibrillation Hospitalization in a Large Sleep-Clinic Cohort Chest. 2015;148(4):945-952.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012369215502833 (OSA and A-fib)

5. Meuleners L, Fraser M, Govorko M, Stevenson M. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Health-Related Factors, and Long Distance Heavy Vehicle Crashes in Western Australia: A Case Control Study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2015; 11(4): 413-418.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4365454/ (OSA and MVA)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

American Sleep Apnea Association

American Sleep Association (ASA)

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1FQ_Hz0ueKYwijOqRSpDrvKPkj7DwaSTRhFksqCUpgE17Q9Y3H|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Strohl KP. Sleep Apnea [Internet]. Kenilworth (NJ): Merck &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Co., Inc.; c2016 [cited 2016 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/sleep-apnea/sleep-apnea

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Young T, Peppard P, Gottlieb D. Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165(9):1217-1239. http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.2109080#.Vu73OZMrKYU (accessed 20 March 2016).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Lam J, Sharma S, Lam B. Obstructive sleep apnea: Definitions, epidemiology &amp;amp; natural history. Indian J Med Res 2010;131:165-170. http://pharexmedics.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/sleepapnea_ebook.pdf (accessed 3 April 2016).

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 Epstein L, Kristo D, Strollo Jr. P, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil S, et al. Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medication 2009; 5(3): 263-276. http://pharexmedics.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/sleepapnea_ebook.pdf (accessed 3 April 2016).

- ↑ Patil SP, Schneider H, Schwartz AR, Smith, PL. Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Pathophysiology and Diagnosis. Chest [Internet]. 2007 Jul [cited 2016 Mar 30];132(1):325-337. Available from: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/article.aspx?articleid=1085264#t1

- ↑ Nieto F, Young T, Lind B, Shahar E, Samet J, Redline S, et al. Association of Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Sleep Apnea, and Hypertension in a Large Community-Based Study. JAMA 2000; 283(14): 1829-1836. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=192578&amp;amp;amp;resultclick=1 (accessed 20 March 2016).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Yaggi H, Concato J, Kernan W, Lichtman J, Brass L, Mohsenin V. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea as a Risk Factor for Stroke and Death. The New England Journal of Medicine 2005; 353:2034-2041. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa043104#t=article (accessed 20 March 2016).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Culpepper L, Roth T. Recognizing and managing obstructive sleep apnea in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 11(6): 330-338. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805569/ (accessed 9 April 2016) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "diagnose3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Fang H, Miao N, Chen C, Sithole T, Chung M. Risk of cancer in patients with insomnia, parasomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea: a nationwide nested case-control study. J Cancer 2015; 6(11): 1140-1147. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4615350/ (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 Booth A, Djavadkhani Y, Marshall N. A critical review of the treatment options available for obstructive sleep apnoea: an overview of the current literature available on treatment methods for obstructive sleep apnoea and future research directions. Bioscience Horizons 2014;7(0):1-8. http://biohorizons.oxfordjournals.org/content/7/hzu011.full.pdf (accessed 4 April 2016).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Tackett K, DeBellis H. USPharmacist.com. Pharmacotherapy Options in the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/d/feature/c/35564/ (accessed 5 April 5 2016).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 10. Shayeb M, Topfer L, Stafinski T, Pawluk L, Menon D. Diagnostic accuracy of level 3 portable sleep tests versus level 1 polysomnography for sleep-disordered breathing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2013; 186(1):E25-E51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3883848/pdf/18600e25.pdf (accessed 7 April 2016).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 11. Maurer J. Early diagnosis of sleep related breathing disorders. GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery 2010; 7(3): 1-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3199834/ (accessed 7 April 2016).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 Downey III R, Rowley J, Wickramasinghe H, Gold P. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Differential Diagnoses. Emedicinemedscapecom. 2016. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/295807-differential. Accessed April 9, 2016.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Schwartz A, Smith P, Oliven A. Electrical stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve: a potential therapy. Journal of Applied Physiology 2013;116(3):337-344. http://jap.physiology.org/content/116/3/337.full (accessed 3 April 2016).

- ↑ Culpepper L, Roth T. Recognizing and managing obstructive sleep apnea in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 11(6): 330-338. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805569/ (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ↑ Cho J, Kim D, Noh K, Kim S, Lee J, Kim J. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy presenting as obstructive type sleep apnea. J Epilepsy Res 2011; 1(2): 74-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3952334/ (accessed 8 April 2016)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 McWhirter D, Bae C, Budur K. The assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of excessive sleepiness: practical considerations for the psychiatrist. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(9): 26-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2880940/ (accessed 9 April 2016).