Sickle Cell Anemia: Difference between revisions

Amanda Scott (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amanda Scott (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

*Seizures | *Seizures | ||

*Cerebrovascular accident | *Cerebrovascular accident | ||

*Meningitis | *Meningitis | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Musculoskeletal | Musculoskeletal | ||

*Avascular necrosis | *Avascular necrosis | ||

*osteomyelitis | *osteomyelitis | ||

*hand | *[http://www.jbjs.org.uk/cgi/reprint/77-B/2/310.pdf hand and foot syndrome] | ||

Visual | Visual | ||

Revision as of 01:02, 31 March 2010

Original Editors - Amanda Scott from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

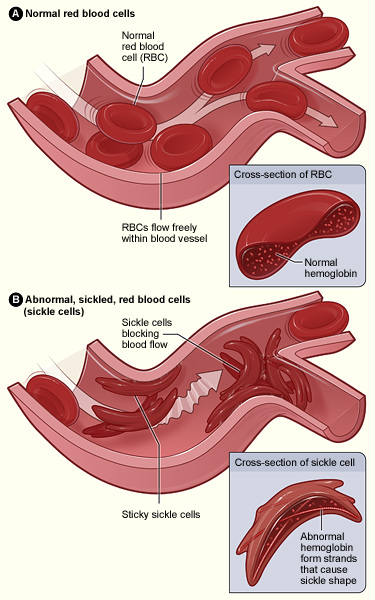

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder characterized by irregularly shaped red blood cells due to an abnormal form of Hemoglobin within the RBC’s. The hemoglobin is able to transport Oxygen in a normal fashion, but once the Oxygen is released, the diseased molecules stick to one another and form abnormally shaped rods in the RBC’s.[1] This in turn, causes the erythrocytes to become sickle shaped and unable to squeeze through the small diametered capillaries, leading to occlusion of these vessels.

This disease was first described by Dr. James Herrick in 1919, who observed a patient from the West Indies whose anemia seemed to be due to sickle shaped red blood cells.[3] In 1956, scientists discovered the gene abnormality within the hemoglobin protein responsible for this disease.[3]

There are various forms of the disease that differ according to the specific type of abnormal hemoglobin inherited. These include hemoglobin SS disease (termed sickle cell anemia and the most prevalent), hemoglobin SC disease, or hemoglobin S Beta thalassemia.[4] The general characteristics of each form are similar, and general treatment is typically the same.

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

50,000-70,000 individuals in U.S. have this disease, with approximately 1000 babies born with it each year. Sickle cell is more prevalent in individuals of African descent, and affects 1 in 400 African American newborns in the U.S.[1] African nations have a much higher incidence of this disease, with approximately 25% of individuals in Western and Central Africa positive for the sickle cell trait.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals with this disorder may vary in their presentation of symptoms. Occlusion of the capillaries by the sickle shaped erythrocytes leads to acute and chronic tissue damage. Clinically, this can lead to widespread pain throughout the body that may last 5 or 6 days.[6] As the name suggests, these patients are anemic, resulting in a presentation of fatigue, pallor and irritability. Acute episodes of symptoms are typical and may be brought on by physical exertion, extreme temperatures, fatigue or recent infections.

Cerebrovascular accidents and acute chest syndrome may also occur as a result of occlusion of the blood vessels.[5] The sickled RBC’s may adhere to the lung endothelium and cause inflammation resulting in acute chest syndrome.[5] This manifests itself as chest pain, fever, coughing, and shortness of breath. Pulmonary hypertension may also result from occlusion in the lungs. Stroke may occur in individuals with sickle cell anemia at a young age and may lead to disability or death.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Jaundice may occur in individuals with sickle cell since liver is unable to process the increased number of dead blood cells, leading to a build up of bilirubin.[5] Hand and foot syndrome may also occur if a clot forms in vessels supplying metacarpal and metatarsal bones. Necrosis of spleen may occur due to its susceptibility to clots. This results in red, tender extremities with possible numbness and tingling.[5] In most children, the spleen is destroyed at an early age as a result of sickle cell disease, posing a significant health risk.[7]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Step 1: mild pain

Non-opioid ± adjuvant

Step 2: moderate pain

Weak opioid (or low dose of strong opioid) ± non-opioid ± adjuvant

Step 3: severe pain

Strong opioid ± non-opioid ± adjuvant

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

All infants in the U.S. must be screened for sickle cells anemia. Blood from the umbilical cord is analyzed using a sickle turbidity test to determine if the abnormal hemoglobin type is present. Electrophoresis can also be used to separate the blood hemoglobin and determine if sickle cell anemia is present.[7] Prenatal diagnosis is possible as early as 10 weeks gestation using amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling at 16 weeks.[5]

Causes[edit | edit source]

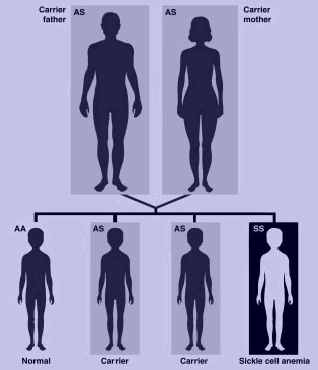

Sickle cell disease is an autosomal recessive disorder, indicating that an individual must inherit two recessive alleles for the disorder to be present.[6] If both parents possess one sickle cell allele, there is a 25% chance that their child will have the disease. The disease results from a mutation that substitutes valine for glutamic acid in the hemoglobin protein. This substitution results in differences in the surface of the red blood cell.[5] A person may have the sickle cell trait if they possess one sickle cell allele; these individuals will be predominantly asymptomatic, but may have some sickle cell symptoms during periods of low oxygen levels.[1]

In the following diagram, both parents are carriers for sickle cell disease. Therefore there is a 25% chance of a genotypically normal child, 50% chance of a child with sickle cell trait (heterzygous), and a 25% chance of a child with sickle cell disease.

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Sickle cell disease may cause widespread complications throughout the body due to decreased blood flow to the organs, as well as tissue damage. Complications include[5]:

Neurological

- Seizures

- Cerebrovascular accident

- Meningitis

Pulmonary

- acute pulmonary infarction

- pneumonia, atelectasis

- chest syndrome

Musculoskeletal

- Avascular necrosis

- osteomyelitis

- hand and foot syndrome

Visual

- blindness

- retinopathy

Genitourinary

- eclampsia

- nocturia

- hematuria

Dermatological

- stasis ulcers of hands, ankles, feet

Other organs

- splenomegaly

- acute hepatomegaly

- gall stones

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Genetic counseling is available to couples who may have the sickle cell trait and are considering having a child.[5] The genetic counselor can explain to the couple the likelihood of having a child with sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait and present various options for the couple.

Bone marrow transplant has been used to successfully cure sickle cell disease.[5] This procedure results in the individual's body producing normal red blood cells and improvement in neurological and pulmonary function has been noted. Bone marrow transplant was first performed as a treatment for sickle cell disease in 1984, and clinical trials demonstrate that 78% of the 116 patients with sickle cell that underwent transplantation were disease free four years following the procedure. However, this may not be available to all patients, and the risk of rejection of donor transplantation prevents some individuals from undergoing this procedure.

Management of pain and anemia symptoms is also given to individuals with sickle cell disease. This may include rest, IV fluids, and pain medications.[5] Hydroxyurea is often used in patients with sickle cell disease. This drug stimulates hemoglobin production and decreases the number of acute episodes a patient experiences.

Furthermore, medical treatment is often necessary to address the many systemic complications of sickle cell disease. For example, blood transfusions have been used to treat patients who have had an acute stroke or acute chest syndrome secondary to sickle cell.[5] Hydroxyurea, vasodilators, and anticoagulatants are often used for treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

There has been research conducted concerning the use of fetal hemoglobin for treatment of sickle cell disease. The introduction of normal hemoglobin helps to prevent sickling of the red blood cells and decrease painful episodes later in life.

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Patient education is extremely important for individuals with sickle cell. They should be educated on the importance of physical activity and remaining mobile in order to combat serious pulmonary and other systemic complications. Furthermore, the patient should be taught breathing techniques and incentive spirometry to also prevent acute chest syndrome and atelectasis, as well as retain adequate lung capacity.[8]

Physical therapists may also work with individuals, especially young children, who have had an acute stroke secondary to sickle cell disease. Therapists would want to address any weakness, loss of function and neuromuscular complications that may have occurred due to the stroke. Though there are no recommended guidelines for this therapy, evidence has shown that children who undergo rehab have good potential for recovery due to neuroplasticity.[9]

Patients with sickle cell disease may have an intolerance to exercise and may fatigue quickly due to anemia. PT's should be mindful of this and gradually work up to moderate levels of exercise with frequent rest breaks. During painful episodes, therapists should avoid overexerting the patient, and should look out for stressors that my include dehydration or cold.[5] Modalities may be helpful during acute pain episodes, but little evidence is available concerning the effectiveness of these strategies.[8]

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Possible differential diagnoses include: chronic anemia, pneumonia,

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

American Sickle Cell Anemia Assocation- http://www.ascaa.org/

Sickle Cell Disease Association of America- http://www.sicklecelldisease.org

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

<div class="researchbox"><rss>Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss></div>

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Campbell NA, Reece JB. Biology: Seventh Edition. San Francisco; Pearson Education: 2005.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Health &amp;amp;amp; Human Services. Sickle Cell Anemia. National Institutes of Health. 2008. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_WhatIs.html. Accessed on March 3, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Brief History of Sickle Cell Disease. Harvard Medical School Research. 2002. http://sickle.bwh.harvard.edu/scd_history.html. Accessed on March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Nemours. Kid’s Health Sickle Cell Disease. Available at http://kidshealth.org/parent/medical/heart/sickle_cell_anemia.html (accessed March 30, 2010).

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis; Saunders Elsevier: 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Goodman CC, Snyder TK. Differential Diagnosis in Physical Therapy. China; Saunders Elsevier: 2000.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sickle Cell Disease of America. What is Sickle Cell Disease. Sickle Cell Disease of America Website. 2005. http://www.sicklecelldisease.org. Accessed on February 28, 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rees DC, Olujohungde AD, Parker NE et al. Guidelines for the Management of the Acute Painful Crisis in Sickle Cell Disease. British J of Haematology. 2003; 120: 744-752.

- ↑ Bernard TJ, Goldenberg NA, Armstrong WA et al. Treatment of Childhood Arterial Stroke. Annals of Neurology. 2008; 63: 679-696.