Sacral Insufficiency Fractures: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

= Clinically Relevant Anatomy = | = Clinically Relevant Anatomy = | ||

Zone 1: involves the sacral ala (lateral to the sacral foramina). This is the most common | The sacrum is a triangular bone formed by 5 vertebral segments. It is broader on the superior side<br>than on the inferior, and broader on the anterior side than on the posterior side, allowing the<br>sacrum to resist shearing from vertical compression (36) as well as transfer loads from the spinal<br>column to the pelvis.(37)<br><br>The sacrum articulates superiorly with the fifth lumbar vertebra and inferiorly with the coccyx. The<br>lateral surface of the upper part of the lateral masses (auricular surface) articulates with the<br>ilium.[5]<br><br>Denis et al classified traumatic sacral fractures by dividing the sacrum into 3 zones (Fig.1).This<br>classification system is based on the direction, the localisation and the level of the fracture.(36)<br>These traumatic fractures are not directly related to SIFs, but the classification system of Denis is<br>very useful for the description of these SIFs.[5]<br><br>Zone 1: involves the sacral ala (lateral to the sacral foramina). This is the most common area of SIFs.<br>Zone 2: involves the sacral (neural) foramina (but the fracture does not enter the central sacral<br>canal). The fractures in this site are associated with unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathies.<br>Zone 3: involves the sacral bodies and the transverse central canal.[2] [5] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 13:48, 16 May 2016

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Keywords:

● Sacral insufficiency fractures

● SIF

● Physical therapy OR Physiotherapy OR Exercise OR Treatment

● Mobilization

● Hydrotherapy OR Aquatherapy

● Medical management AND SIF

● SIF AND examination

Databases:

● Pubmed

● Web of Knowledge

● PEDro

● Google scholar

● Google

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sacral insufficiency fractures (SIFs) are a cause of low back pain.[1]

They are a subtype of stress fractures, resulting from normal stress applied to a bone with reduced

elasticity.[2] [3]

An underlying condition, like osteoporosis or another metabolic bone disease, is often a cause of

SIFs. This is why SIFs are more common with elderly women.[2] [3][4] Bone insufficiency fractures

in general are described first by Laurie in 1982.[3][4]

During the gait, alternating flexion and extension of the lower limbs would impart alternating

twisting forces on the pelvis around its lowest transverse axis. This effect can be shown in a

pretzel-model. When we hold a pretzel in two hands and twist it around its long axis in alternating

directions, the pretzel will snap eventually. This is what happens clinically with the sacrum during

insufficiency fractures.

As previously mentioned, this happens most frequently with elderly women, whose sacroiliac joint

is relatively ankylosed and whose sacrum has been weakend by osteoporosis. Under these

conditions, the torsional stress which is normally buffered by the sacroiliac joint, will be transferred

to the sacrum. Because of the conditions of the weakend sacrum, it fails to buffer the torsional

stress and fractures occur. In most cases, these fractures run vertically through the ala of the

sacrum parallel to the sacroiliac joint.(33)

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

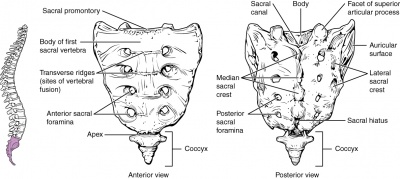

The sacrum is a triangular bone formed by 5 vertebral segments. It is broader on the superior side

than on the inferior, and broader on the anterior side than on the posterior side, allowing the

sacrum to resist shearing from vertical compression (36) as well as transfer loads from the spinal

column to the pelvis.(37)

The sacrum articulates superiorly with the fifth lumbar vertebra and inferiorly with the coccyx. The

lateral surface of the upper part of the lateral masses (auricular surface) articulates with the

ilium.[5]

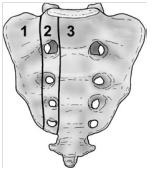

Denis et al classified traumatic sacral fractures by dividing the sacrum into 3 zones (Fig.1).This

classification system is based on the direction, the localisation and the level of the fracture.(36)

These traumatic fractures are not directly related to SIFs, but the classification system of Denis is

very useful for the description of these SIFs.[5]

Zone 1: involves the sacral ala (lateral to the sacral foramina). This is the most common area of SIFs.

Zone 2: involves the sacral (neural) foramina (but the fracture does not enter the central sacral

canal). The fractures in this site are associated with unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathies.

Zone 3: involves the sacral bodies and the transverse central canal.[2] [5]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The most important cause of SIF is osteoporosis.[1] [2] [3] [4] Other risk factors are:

- Pelvic radiation

- Steroid-induced osteopenia [4]

- Rheumatoid arthritis [3]

- Multiple myeloma

- Paget disease [4]

- Renal osteodystrophy

- Hyperparathyroidism [1] [5] [2] [4]

- Corticosteroid medication [1] [2]

- Metastatic disease [1] [2]

- Marrow replacement processes [1] [2]

- Fibrous dysplasia [5]

- Osteogenesis imperfect [5]

- Osteopetrosis [5]

- Osteomalacia [5]

Patients with SIFs are mostly time older than 55 years old. The mean age is between 70 and 75 years old.

The precise incidence of SIFs is unknown but some studies reported a prevalence of 1% - 5% in at-risk patient populations.

Two-third of patients were a-traumatic. [1]

SFI can occur in a younger population. For example: pregnant women. This can be related to pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. [5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with SIFs may have:

- Tenderness of palpation (lower back and sacral region) [1] [6] [2] [3]

- Pain (at the buttock, back, hip, pelvic or groin) [7]

- Problems with walking (slowly and painful)

- Nerve damage (unusual) [1] [2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Sacral insufficiency fractures are difficult to diagnose because the signs and symptoms are vague and non-specific.

SIFs can be confused with:

- Metastatic disease [2]

- Radiculopathy [1]

- Disc disease

- Spinal stenosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

SIF can be diagnosed with radiology. Bone scintigraphy is the most sensitive study to detect SIFs. Other radiographic procedures that can help to diagnose SIFs are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans. [1] [2] [8]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination shows: [9]

- Sacral tenderness (on lateral compression)

- SI-joint tests are often positive (this test is not specific for SFI)

- Gait is slow and antalgic

- Trendelenburg test is normal

- Sciatic nerve tension tests (Lasegue and Straight Leg Raise (SLR)) are normal

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Early rehabilitation and moderate weight-bearing exercises, within the boundaries of pain tolerance, have been suggested. Earlier rehabilitation will stimulate the bone formation by the osteoblasts and improve muscle tension.

Mobilization is recommended because long periods of immobilization can result in complications (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, loss of muscle strength, etc.). In the earlier stages of fracture healing, mobilization can be assisted by the use of external devices (e.g. walking frames) or hydrotherapy as these are typically tolerated better by many patients. [9]

Resources[edit | edit source]

http://www.artrose-blog.nl/rugaandoeningen/insufficientiefracturen-van-het-sacrum

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLyders - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWild - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Dasgupta B., Shah N., Brown H., Gordon T.E., Tanqueray A.B., Mellor J.A., Sacral insufficiency fractures: an unsuspected cause of low back pain. British Journal of Rheumatology 1998; 37: 789-793.(Levels of evidence: B)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedYong - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 KARATAS M., BASARAN C., OZGUL E., TARHAN E., AGILDERE A.M., Postpartum sacral stress fracture, An unusual case of low-back and buttock pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Vol 87, No. 5. 2008.(Levels of evidence: C)

- ↑ KOS C.B., TACONIS W.K., VAN DER EIJKEN J.W., Insufficiëntiefracturen van het sacrum, Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd 1999, 13 februari; 143(7).(Levels of evidence: C)

- ↑ THEIN R., BURSTEIN G., SHABSHIN N., Labor-related sacral stress fracture presenting as lower limb radicular pain. Orthopedics June 2009; 32(6):447.(Levels of evidence: B)

- ↑ GOTIS-GRAHAM I., McGUIGAN L., DIAMOND T., PORTEK I., QUINN R., STURGESS A., TULLOCH R., Sacral insufficiency fractures in the elderly. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994; 76-B: 882-6.(Levels of evidence: B)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTsiridis