Remote Screening for Lumbar Spine Red Flags

Introduction

Clinical findings that increase the level of suspicion that there is a serious medical condition described as red flags (Finucane L. 2020), They are key for patient safety so often a component of clinical guidelines for the assessment and management of people with low back pain (Ferguson, Morison and Ryan, 2015). Red flags are features from a patient's subjective and objective assessment which are thought to put them at a higher risk of serious pathology and warrant referral for further diagnostic testing (Delitto, George, and Godges. 2012).

Physiotherapists understanding of red flags for low back pain

The role of physiotherapists as primary identifiers of red flags has grown owing to the spread of self‐referral services (Holdsworth et al., 2006). Physiotherapists often exists without any medical input or review (Kersten et al., 2007; McPherson et al., 2006). Therefore, there is a need to ensure that physiotherapists have a good understanding of individual red flags, understand their importance, and can ask these questions in a clear and unambiguous manner. Similarly, physiotherapists must have a clear understanding and agreed pathways of care dependent on these findings. Failure to do so raises issues around patient safety and professional reputation.

Epidemiology of Red flags

One study aimed to investigate which red flags do physiotherapists routinely record; which red flags do they consider to be most important; how would they define each red flag; and how they would ask each red‐flag question to a person with back pain (Ferguson, Morison and Ryan, 2015). 98 physiotherapists responded to the survey, 84% worked exclusively in the National Health Service (NHS). They recorded that ‘Previous history of cancer’, ‘saddle anaesthesia’ and ‘difficulty with micturition’ were the red flags with the highest level of importance attached to them to rise suspicion to serious pathologies. Definitions of were as follows, history of cancer: ‘an individual who has previously been diagnosed with cancer’. And Saddle anaesthesia: Since your symptoms commenced, have you noticed any pins and needles or numbness around your back passage or genital area’. Finally, limited consensus was found in how physiotherapists asked patients about red flags. However, one theme in ponticular emerged, which is the use of nebulous terminology - for example, the terms recent, weight loss and prolonged period.

Cauda Equina

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare but potentially devastating neurological condition affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord called the cauda equina (CE). The CE is responsible for the innervation of the lower limbs, control of the sphincter, regulation and function of the bladder and distal bowel and sensation to the skin around the bottom and back passage [1].

There is large debate over CES, consequently there is no agreed definition, however, the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS) present a definition that is useful in clinical practice.Tsiang et al. (2019)

'A patient presenting with acute back pain and/or leg pain with a suggestion of a disturbance of their bladder or bowel function and/or saddle sensory disturbance should be suspected of having a CES. Most of these patients will not have critical compression of the cauda equina. However, in the absence of reliably predictive symptoms and signs, there should be a low threshold for investigation with an emergency scan’

CES may present at any time or in any setting and it is imperative that clinicians are able to quickly reason through their findings to manage the patient effectively.

Epidemiology

There are many causes of CES, but the most common cause is that of a lumbar spine disc herniation and it occurs most frequently between the ages of 31–50 (Fuso et al., 2013). Cauda equina compression usually occurs as a result of a disc prolapse, often at the L4/5 level (Fraser et al., 2009). However, any space-occupying lesion, such as spinal stenosis, tumour, cysts, infection, or bony ingress can narrow the spinal canal and cause compression of the cauda equina.

Published estimates of the incidence for CES are fewer than one per 100 000 population (Hurme et al., 1984; Podnar, 2007). However, in 2010–2011 in England, 981 surgical decompressions were performed for CES (The National Spinal Taskforce, 2013) and the population was estimated at 52 234 000 (Office for National Statistics, 2011) giving an incidence of 1.9 per 100 000. Therefore, there may be over 1000 patients managed for CES in the UK each year.

In a primary care setting, ‘Table 1’ highlights the incidence of diagnose given for CES in the UK 2018/19 (Barnes, 2019).

| Condition | Number of primary diagnoses | % of total cases |

| Low Back Pain | 45,520 | 0.04% |

| Cauda Equina Syndrome | 170 | 0.0% |

| Malignant Neoplasm (Cancer): Cauda Equina | 58 | 0.0% |

Malignancy

The spinal cord may be compressed due to tumours occupying space within the vertebral canal (Gilbert et al. 1978). This may then affect the neural function of the spinal cord causing unremitting pain, muscle power and sensation alteration, sexual dysfunction, bladder/bowel dysfunction and sleep disturbances (cancerresearchuk.org, 2020).

Epidemiology

Tumours are classified as primary, originating in the spine, and secondary, originating elsewhere in the body and spreading to the spine (cancerresearchuk.org). Secondary tumours are much more prevalent than primary tumours. They occur in approximately 70% of cancer patients (Ciftdemir et al. 2016) whereas primary tumours occur in approximately 0.07% of healthy people (Schellinger et al. 2008). The most common types of primary tumours are meningiomas (29%), nerve-sheath tumours (24%) and ependymomas (23%) (Schellinger et al. 2008). Secondary tumours can metastasise from many different areas of the body; most commonly they may spread from breast, lung and prostate primary tumours (John Hopkins Medicine, 2020).

In a primary care setting, malignancy is extremely rare. ‘Table 1’ highlights the incidence primary diagnoses given that may result in low back pain within NHS primary care settings in the UK in 2018/19. 96,420,114 patients were seen in total (Barnes, 2019).

| Condition | Number of primary diagnoses | % of total cases |

| Low back pain | 45,520 | 0.04% |

| Malignant neoplasm: Vertebral column | 136 | 0.00% |

| Malignant neoplasm: Connective and soft tissue of trunk | 85 | 0.00% |

| Malignant neoplasm: Spinal meninges | 1 | 0.00% |

| Malignant neoplasm: CNS unspecified | 233 | 0.00% |

| Malignant neoplasm of other and ill-defined sites: Lower limb | 74 | 0.00% |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of other unspecified parts of the nervous system | 158 | 0.00% |

| Secondary malignant neoplasm of bone and bone marrow | 17,629 | 0.02% |

Prognosis

Around 10-20% of patients diagnosed with spinal metastasis live for longer than two years after this diagnosis (Delank et al. 2011). Better prognoses and longer survival rates have been associated with earlier detection of the tumour (Ruckdeschel, 2005). Therefore, it is important to screen patients with low back pain for red flags associated spinal malignancy.

Clinical Indicators

When assessing patients with low back pain, there are a number of ‘red flags’ which may increase suspicion of spinal malignancy. Large scale studies by Henschke et al. (2013), Premkumar et al. (2018) and Tsiang et al. (2019) have identified numerous clinical indicators of malignancy that should be screened for during the assessment of these patients.

These studies accept that no single ‘red flag’ can be used in isolation to give a diagnosis of spinal malignancy. Instead, a combination may increase a clinician’s index of suspicion. The literature stated that patient-reported history of cancer, alongside low back pain, was identified as the most significant sign of spinal malignancy. Interestingly, Premkumar et al. (2018) reported that a past medical history of cancer, combined with unexplained weight loss, produced a specificity of 99.8%. The summary of findings from these studies is detailed in table X below.

| Indicator | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Age >50 | 71.7 | 32.6 |

| Age >70 | 22.6 | 79.5 |

| Night pain | 54.2-55.4 | 41.8-49.6 |

| Unexplained weight loss | 8.2 | 95.6 |

| Pain at rest | 25 | 69.8 |

| Urinary retention | 4.2 | 95.8 |

| History of cancer | 32-75 | 78.7-95.6 |

| History of cancer + Unexplained weight loss | 2.5 | 99.8 |

A Cochrane review carried out by Henschke et al. (2013) examining studies containing over 6000 patients emphasised the need for an affective diagnostic test to assist in the identification of spinal malignancy in patients with low back pain.

Vertebral fractures

Last year, out of the 96,420,114 patients who were assessed in a primary care setting only 524 were diagnosed as having a Lumbar vertebral fracture. There were 498 diagnosed with a Fracture of other and unspecified parts of lumbar spine and pelvis, and 10 diagnosed with Multiple fractures of Lumbar spine and pelvis (NHS digital, 2019).

The actual incidence of vertebral fractures is likely much greater given the large number of vertebral fractures that go undetected. More than two-thirds of patients with Vertebral fractures are asymptomatic, and are diagnosed incidentally (Fink, 2005). Symptomatic patients may report abrupt onset of pain with position changes, coughing, sneezing, or lifting. Physical examination findings are often normal but may demonstrate kyphosis and midline spine tenderness.

A vertebral fracture not only requires specific appropriate treatment, but is a contraindication to spinal manipulative therapy, a common treatment that is endorsed in clinical practice guidelines for acute nonspecific low back pain. Therefore, accurate diagnosis in primary care is essential to prevent poor outcome

Epidemiology

Ballane (2017) investigated the prevalence and incidence of vertebral fractures worldwide using a total of 62 articles of fair to good quality and comparable methods for vertebral fracture identification were considered. Graphs A and B display age-standardized incidence rates in men and women combining hospitalized and ambulatory vertebral fractures, ranked by descending incidence. Standardization to 2010 UN population (a) and 2015 UN population (b

(Ballane,. 2017)

Rates partially depend on the definition of vertebral fracture, clinical versus morphometric. The morphometric definition is not universal; at least seven methods have been used in different studies (included in Graphs A and B). Within the same method, varying decision thresholds (fracture grade or standard deviation from means) make the definition of vertebral fracture even more difficult. Different definitions include of vertebral fracture include: - Morphometric method - McCloskey method - Eastell method - Genant Method - Davies method - Melton method - Denis Classification

Diagnosis

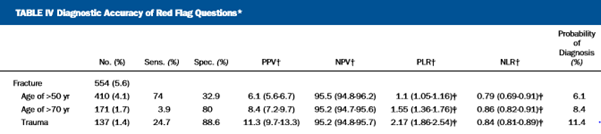

In the primary care setting, between 1% and 5% of all patients who present with LBP will have a serious spinal pathology which requires further assessment and often specific treatment (Deyo 1992; Henschke 2009). The most common of these serious spinal pathologies which initially manifests as LBP is vertebral fracture, followed by malignancy, infection, and inflammatory disease. The presence of a "red flag" should alert clinicians to the need for further examination and in most cases, specific management (Waddell 2004). With respect to vertebral fractures, the typical “red flags” include >50 years of age, Prolonged corticosteroid use, Trauma and Osteoporosis. High quality evidence investigating the efficacy of these “red flags” correctly identifying serious pathologies has been investigated in studies such as Premkumar et al. (2018) and Tsiang et al. (2019).

| Osteoporosis | Steroid Use | Trauma | Sensitivity

(95% CI) |

Specificity

(95% CI) |

TP (%) | FP (%) | FN (%) | TN (%) |

| X | .415 (.281-.559) | .762 (.719-.802) | 4.6 | 21.1 | 6.5 | 67.7 | ||

| X | .283 (.168-.423) | .867 (.831-.898) | 3.2 | 11.8 | 8.0 | 77.0 | ||

| X | .226 (.123-.362) | .938 (.911-.959) | 2.5 | 5.5 | 8.6 | 83.3 | ||

| X | X | .528 (.386-.667) | .694 (.647-.737) | 5.9 | 27.2 | 5.3 | 61.6 | |

| X | X | .509 (.368-.649) | .713 (.667-.755) | 5.7 | 25.5 | 5.5 | 63.3 | |

| X | X | .415 (.281-.559) | .815 (.774-.851) | 4.6 | 16.5 | 6.5 | 72.4 | |

| X | X | X | .585 (.441-.719) | .648 (.601-.694) | 6.5 | 31.2 | 4.6 | 57.6 |

Tsiang et al. (2019).

Premkumar et al. (2018)

Premkumar et al. (2018)

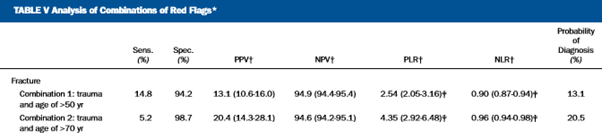

The presence of both recent trauma and an age of >50 years carries a 13.1% probability of a vertebral fracture in the setting of low back pain; Tsiang et al. (2019). The presence of both recent trauma and an age of >70 years carries a 20.5% probability of vertebral fracture in the setting of low back pain. Tsiang et al. (2019).

Clinical implications

There is agreement in the current literature the findings give rise to a weak recommendation that a combination of a small subset of red flags may be useful to screen for vertebral fracture. It should also be noted that many red flags have high false positive rates; and if acted upon uncritically there would be consequences for the cost of management and outcomes of patients with LBP.

References

Ballane, G., Cauley, J., Luckey, M. and El-Hajj Fuleihan, G., 2017. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoporosis International, 28(5), pp.1531-1542.

Barnes, M., 2019. NHS Digital, Hospital Episode Statistics For England. Outpatient Statistics, 2018 - 2019.. Primary Diagnosis by Attendance Type. NHS Digital.

Cancerresearchuk.org. 2020. Spinal Cord Compression | Cancer In General | Cancer Research UK. [online] Available at: <https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/physically/spinal-cord-compression/about> [Accessed 20 May 2020].

Cancerresearchuk.org. 2020. Spinal Cord Tumours (Primary) | Cancer Research UK. [online] Available at: <https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/brain-tumours/types/treatment-spinal-cord-tumours> [Accessed 20 May 2020].

Ciftdemir, M., Kaya, M., Selcuk, E. and Yalniz, E., 2016. Tumors of the spine. World journal of orthopedics, 7(2), p.109.

Delank, K.S., Wendtner, C., Eich, H.T. and Eysel, P., 2011. The treatment of spinal metastases. Deutsches Aerzteblatt International, 108(5), p.71.

Delitto, A., George, S. and Godges. J, 2012. Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of orthopaedics and sports physical therapy. 42(4), pp. 57

Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain?. Journal of the American Medical Association 1992;268(6):760‐5.

Ferguson, F.C., Morison, S. and Ryan, C.G., 2015. Physiotherapists' understanding of red flags for back pain. Musculoskeletal care, 13(1), pp.42-50.

Fink HA, Milavetz DL, Palermo L, et al.; Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. What proportion of incident radiographic vertebral deformities is clinically diagnosed and vice versa? J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(7):1216–1222

Finucane L. 2020. An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology.

Fraser, S., Roberts, L. and Murphy, E., 2009. Cauda equina syndrome: a literature review of its definition and clinical presentation. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 90(11), pp.1964-1968.

Fuso, F.A.F., Dias, A.L.N., Letaif, O.B., Cristante, A.F., Marcon, R.M. and de Barros Filho, T.E.P., 2013. Epidemiological study of cauda equina syndrome. Acta ortopedica brasileira, 21(3), p.159.

Gilbert, R.W., Kim, J.H. and Posner, J.B., 1978. Epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic tumor: diagnosis and treatment. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society, 3(1), pp.40-51.

Henschke, N., Maher, C.G., Ostelo, R.W., de Vet, H.C., Macaskill, P. and Irwig, L., 2013. Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low‐back pain. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (2).

Holdsworth, L.K., Webster, V.S., McFadyen, A.K. and Scottish Physiotherapy Self-Referral Study Group, 2006. Self-referral to physiotherapy: deprivation and geographical setting: is there a relationship? Results of a national trial. Physiotherapy, 92(1), pp.16-25.

John Hopkins Medicine. 2020. Spinal Cancer And Spinal Tumors. [online] Available at: <https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/spinal-cancer-and-spinal-tumors> [Accessed 20 May 2020].

Kersten, P., McPherson, K., Lattimer, V., George, S., Breton, A. and Ellis, B., 2007. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice–who is doing what and why?. Physiotherapy, 93(4), pp.235-242.

McPherson, K., Kersten, P., George, S., Lattimer, V., Breton, A., Ellis, B., Kaur, D. and Frampton, G., 2006. A systematic review of evidence about extended roles for allied health professionals. Journal of health services research & policy, 11(4), pp.240-247.

Patel U, Skingle S, Campbell GA, Crisp AJ, Boyle IT. Clinical profile of acute vertebral compression fractures in osteoporosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30(6):418–421

Premkumar, A., Godfrey, W., Gottschalk, M.B. and Boden, S.D., 2018. Red flags for low Back pain are not always really red: a prospective evaluation of the clinical utility of commonly used screening questions for low Back pain. JBJS, 100(5), pp.368-374.

Ruckdeschel, J.C., 2005. Early detection and treatment of spinal cord compression. Oncology, 19(1).

Schellinger, K.A., Propp, J.M., Villano, J.L. and McCarthy, B.J., 2008. Descriptive epidemiology of primary spinal cord tumors. Journal of neuro-oncology, 87(2), pp.173-179.

Todd, N.V., 2017. Guidelines for cauda equina syndrome. Red flags and white flags. Systematic review and implications for triage. British journal of neurosurgery, 31(3), pp.336-339.

Tsiang, J.T., Kinzy, T.G., Thompson, N., Tanenbaum, J.E., Thakore, N.L., Khalaf, T. and Katzan, I.L., 2019. Sensitivity and specificity of patient-entered red flags for lower back pain. The Spine Journal, 19(2), pp.293-300.

Verhagen, A.P., Downie, A., Popal, N., Maher, C. and Koes, B.W., 2016. Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review. European Spine Journal, 25(9), pp.2788-2802.

Patel U, Skingle S, Campbell GA, Crisp AJ, Boyle IT. Clinical profile of acute vertebral compression fractures in osteoporosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30(6):418–421

Waddell G. The Back Pain Revolution. 2nd Edition. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.