Promoting Active Living in Young People Through Behaviour Change: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

The physical and mental behaviour of today’s adolescent generation are determinants of their growth and development, now and throughout their lifespan <ref>Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005 Apr 1;28(3):267-73.</ref> <ref>Obesity and overweight reports [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/</nowiki></ref>. Technological advances of today’s society have contributed to sedentary lifestyles, causing young people to have an increased body weight and body mass index (BMI) than from one generation earlier<ref>Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):483-90.</ref>. The gradual increase of routine sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is a major contributor to chronic health conditions and is strongly correlated with the diagnosis of these diseases <ref>Hills AP, King NA, Armstrong TP. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents. Sports medicine. 2007 Jun 1;37(6):533-45.</ref> [27SA]. This trend is at risk for continuing with today's young generation, as research suggests that the levels of physical activity decreases between the ages of 11-15 [IB5].Globally, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, causing 3.2- 5 million deaths annually <ref>Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, Van Mechelen W, Pratt M, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1311-24.</ref> <ref>Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.</ref> <ref>World Health organization WHO. Global Health Risks-Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Cancer. 2017 Feb 3.</ref>. While many of these chronic diseases are identified in adulthood, research suggests that the development of these conditions originate in childhood and adolescence <ref>Hallal PC, Victora CG, Azevedo MR, Wells JC. Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports medicine. 2006 Dec 1;36(12):1019-30. | The physical and mental behaviour of today’s adolescent generation are determinants of their growth and development, now and throughout their lifespan <ref name=":2">Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005 Apr 1;28(3):267-73.</ref> <ref name=":3">Obesity and overweight reports [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/</nowiki></ref>. Technological advances of today’s society have contributed to sedentary lifestyles, causing young people to have an increased body weight and body mass index (BMI) than from one generation earlier<ref>Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):483-90.</ref>. The gradual increase of routine sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is a major contributor to chronic health conditions and is strongly correlated with the diagnosis of these diseases <ref>Hills AP, King NA, Armstrong TP. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents. Sports medicine. 2007 Jun 1;37(6):533-45.</ref> [27SA]. This trend is at risk for continuing with today's young generation, as research suggests that the levels of physical activity decreases between the ages of 11-15 [IB5].Globally, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, causing 3.2- 5 million deaths annually <ref name=":4">Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, Van Mechelen W, Pratt M, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1311-24.</ref> <ref>Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.</ref> <ref name=":5">World Health organization WHO. Global Health Risks-Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Cancer. 2017 Feb 3.</ref>. While many of these chronic diseases are identified in adulthood, research suggests that the development of these conditions originate in childhood and adolescence <ref>Hallal PC, Victora CG, Azevedo MR, Wells JC. Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports medicine. 2006 Dec 1;36(12):1019-30. | ||

</ref> <ref>Halfon N, Verhoef PA, Kuo AA. Childhood antecedents to adult cardiovascular disease. Pediatrics in Review. 2012 Feb;33(2):51-60.</ref>. Furthermore, young people may have a less impressionable attitude towards their body image than adults, which may provide less resistance with behavioural change interventions <ref>Beckman H, Hawley S, Bishop T. Application of theory-based health behavior change techniques to the prevention of obesity in children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006 Aug 1;21(4):266-75.</ref> <ref>Kater KJ, Rohwer J, Levine MP. An elementary school project for developing healthy body image and reducing risk factors for unhealthy and disordered eating. Eating Disorders. 2000 Mar 1;8(1):3-16.</ref>. Therefore, the promotion of healthy behavioural habits must be learned during adolescent years, which will help carry forward the same behaviour into adulthood. Behaviours of active living established in early years can provide the greatest impact on maintaining these positive habits across one’s lifespan and influence mortality and longevity <ref>Paffenbarger Jr RS, Hyde R, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. New England journal of medicine. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):605-13.</ref> <ref>Harold W. Kohl, I., Cook, H., Environment, C., Board, F. and Medicine, I. (2018). Physical Activity and Physical Education: Relationship to Growth, Development, and Health. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201497/</nowiki>\ [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].</ref>. | </ref> <ref>Halfon N, Verhoef PA, Kuo AA. Childhood antecedents to adult cardiovascular disease. Pediatrics in Review. 2012 Feb;33(2):51-60.</ref>. Furthermore, young people may have a less impressionable attitude towards their body image than adults, which may provide less resistance with behavioural change interventions <ref>Beckman H, Hawley S, Bishop T. Application of theory-based health behavior change techniques to the prevention of obesity in children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006 Aug 1;21(4):266-75.</ref> <ref>Kater KJ, Rohwer J, Levine MP. An elementary school project for developing healthy body image and reducing risk factors for unhealthy and disordered eating. Eating Disorders. 2000 Mar 1;8(1):3-16.</ref>. Therefore, the promotion of healthy behavioural habits must be learned during adolescent years, which will help carry forward the same behaviour into adulthood. Behaviours of active living established in early years can provide the greatest impact on maintaining these positive habits across one’s lifespan and influence mortality and longevity <ref>Paffenbarger Jr RS, Hyde R, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. New England journal of medicine. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):605-13.</ref> <ref>Harold W. Kohl, I., Cook, H., Environment, C., Board, F. and Medicine, I. (2018). Physical Activity and Physical Education: Relationship to Growth, Development, and Health. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: <nowiki>https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201497/</nowiki>\ [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].</ref>. | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

The World Health Organization’s physical activity guidelines to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular and bone health as well as metabolic health biomarkers for young people as shown in the Figure below <ref name=":1">Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/</nowiki></ref>. | The World Health Organization’s physical activity guidelines to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular and bone health as well as metabolic health biomarkers for young people as shown in the Figure below <ref name=":1">Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/</nowiki></ref>. | ||

[[File:Screen Shot 2018-04-14 at 3.42.01 PM.png|center|thumb|650x650px|Figure 2: World Health Organization's <ref>Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/</nowiki></ref> Physical Activity Guidelines for children and young people.]] | [[File:Screen Shot 2018-04-14 at 3.42.01 PM.png|center|thumb|650x650px|Figure 2: World Health Organization's <ref name=":6">Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/</nowiki></ref> Physical Activity Guidelines for children and young people.]] | ||

Physical activity for young people in the context of family, school and community activities includes <ref name=": | Physical activity for young people in the context of family, school and community activities includes <ref name=":6" />: | ||

* Play | * Play | ||

* Games | * Games | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

== Epidemiology, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: == | == Epidemiology, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: == | ||

* Research suggests that on average 39% of adults in the UK are not physically active <ref>Physical Inactivity Report 2017 [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2017 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017</nowiki></ref>. Physical inactivity causes 3.2-5 million global deaths annually and is the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality<ref | * Research suggests that on average 39% of adults in the UK are not physically active <ref>Physical Inactivity Report 2017 [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2017 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017</nowiki></ref>. Physical inactivity causes 3.2-5 million global deaths annually and is the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":7">Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.</ref> <ref name=":5" />. | ||

* Sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is strongly correlated to the diagnosis of many chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity [27 SA] | * Sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is strongly correlated to the diagnosis of many chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity [27 SA] | ||

* Nearly half of the young population in the UK are sedentary apart from school activities [ | * Nearly half of the young population in the UK are sedentary apart from school activities <ref>Physical activity statistics [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2015 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-activity-statistics-2015</nowiki></ref> <ref name=":8">Scholes S, Mindell J. Health Survey for England 2012: Physical activity in children. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre. 2013.</ref> <ref name=":9">Arundell L, Fletcher E, Salmon J, Veitch J, Hinkley T. A systematic review of the prevalence of sedentary behavior during the after-school period among children aged 5-18 years. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2016 Dec;13(1):93.</ref>. Common sedentary activities include: screen-based sedentary behaviour, social sedentary behaviour, TV-viewing, homework and academics and lastly motorized transport<ref name=":9" />. | ||

* It is predicted that the 4.1 million children and young people who are obese and overweight globally are likely to remain obese and overweight into adulthood leading to greater risk of developing non-communal diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions at a younger age | * It is predicted that the 4.1 million children and young people who are obese and overweight globally are likely to remain obese and overweight into adulthood leading to greater risk of developing non-communal diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions at a younger age <ref name=":7" /> <ref name=":3" /> | ||

* 13% of the youth aged between 11-15 year olds in England are not meeting the physical activity recommendations [ | * 13% of the youth aged between 11-15 year olds in England are not meeting the physical activity recommendations <ref name=":8" /> <ref>Streetgames.org. (2014). [online] Available at: <nowiki>https://www.streetgames.org/sites/default/files/The-Inactivity-TimeBomb-StreetGames-Cebr-report-April-2014.pdf</nowiki> [Accessed 17 Mar. 2018].</ref>. | ||

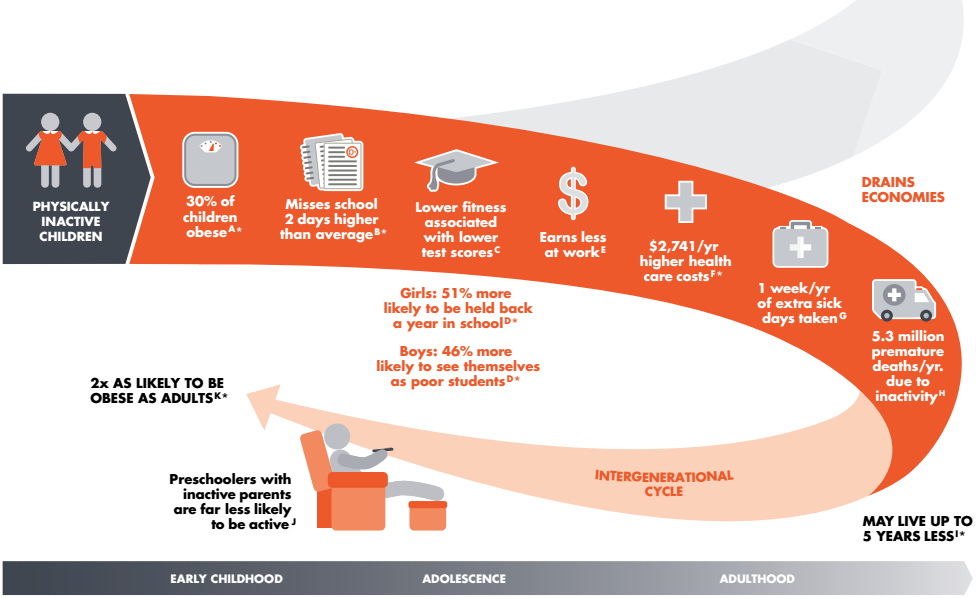

* Increased sedentary behavior has been shown to greatly affect the health outcomes such as increased risk of obesity rates, lowered cardiorespiratory fitness and lowered insulin sensitivity in young people aged between 11-18 years old | * Increased sedentary behavior has been shown to greatly affect the health outcomes such as increased risk of obesity rates, lowered cardiorespiratory fitness and lowered insulin sensitivity in young people aged between 11-18 years old <ref>Mitchell JA, Byun W. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes in children and adolescents. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2014 May;8(3):173-99.</ref> <ref>Boreham C, Riddoch C. The physical activity, fitness and health of children. Journal of sports sciences. 2001 Jan 1;19(12):915-29. | ||

[[File:Physically Inactive Children.png|center|Figure 4: Consequences of physical inactivity in children and adolescents progressing into adulthood. | </ref> <ref>Malina RM. Physical fitness of children and adolescents in the United States: status and secular change. InPediatric Fitness 2007 Jan 1;50:67-90. </ref> <ref>Steele RM, Brage S, Corder K, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome in youth. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2008 Jul;105(1):342-51.</ref>. However, alarmingly physical activity levels tend to drop off from ages 11-15 in most european countries [IB5] | ||

[[File:Physically Inactive Children.png|center|Figure 4: Consequences of physical inactivity in children and adolescents progressing into adulthood. <ref>Nike (2013). Designed to Move: A Physical Activity Action Agenda™. [image] Available at: <nowiki>https://clubs.marathonkids.org/keeping-kids-moving/</nowiki> [Accessed 17 Mar. 2018].</ref> |frame]] | |||

== Justification for the emerging role within Physiotherapy == | == Justification for the emerging role within Physiotherapy == | ||

| Line 87: | Line 88: | ||

[[File:Economic Implications 1.png|thumb|433x433px|Figure 5: Estimated healthcare costs (measured in 2013 prices) for the young population aged 10-25 whom are currently failing to meet recommendations for physical activity [16AM]]] | [[File:Economic Implications 1.png|thumb|433x433px|Figure 5: Estimated healthcare costs (measured in 2013 prices) for the young population aged 10-25 whom are currently failing to meet recommendations for physical activity [16AM]]] | ||

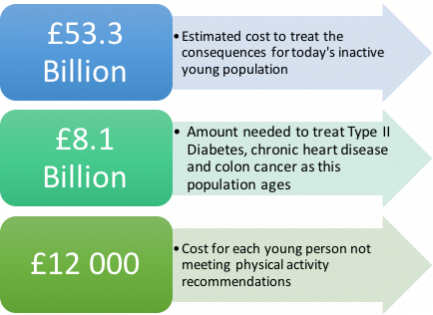

Establishing routine physical activity as an adolescent is associated with an increased probability to continue this behaviour into adulthood and a reduced risk of disease | Establishing routine physical activity as an adolescent is associated with an increased probability to continue this behaviour into adulthood and a reduced risk of disease <ref name=":2" />. However, with nearly half of young people aged 10-24 not achieving the recommended physical activity guidelines <ref name=":1" />, the healthcare costs to communities and the NHS are under strain. In Scotland, physical inactivity causes 2500 deaths per year and costs the NHS £91 million per year <ref>Beta.gov.scot. (2018). Physical activity and sport - gov.scot. [online] Available at: <nowiki>https://beta.gov.scot/policies/physical-activity-sport/</nowiki> [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].</ref>. In the UK, the levels of physical inactivity in young people will result in predicted diseases, decreased quality of life and reduced lifespan. The economic costs of these anticipated morbidities are estimated in Figure 5. | ||

If the total number of young people meeting physical activity guidelines could increase by only 1%, the UK could save £0.8 billion. Figure 6 displays the viable economic savings associated with young people’s increase in physical activity. | If the total number of young people meeting physical activity guidelines could increase by only 1%, the UK could save £0.8 billion. Figure 6 displays the viable economic savings associated with young people’s increase in physical activity. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 97: | ||

=== Barriers to physical activity: === | === Barriers to physical activity: === | ||

There are several barriers to physical activity and active living that are perceived by young people and parents, which varies from personal preferences, access to facilities and opportunities as shown below | There are several barriers to physical activity and active living that are perceived by young people and parents, which varies from personal preferences, access to facilities and opportunities as shown below <ref name=":10">Wright A, Roberts R, Bowman G, Crettenden A. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disability and rehabilitation. 2018 Jan 30:1-9.</ref> <ref name=":11">Brunton G, Harden A, Rees R, Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Oakley A. Children and physical activity: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators.</ref> <ref name=":12">Martins J, Marques A, Sarmento H, Carreiro da Costa F. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health education research. 2015 Aug 31;30(5):742-55.</ref> <ref name=":13">Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status?. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2003 Apr 1;25(2):100-4.</ref> <ref name=":14">Eyre EL, Duncan MJ, Birch SL, Cox VM. Low socio-economic environmental determinants of children's physical activity in Coventry, UK: A Qualitative study in parents. Preventive medicine reports. 2014 Jan 1;1:32-42.</ref>: | ||

# Preferences and Priorities: | # Preferences and Priorities: | ||

* Sports or exercise is not enjoyable | * Sports or exercise is not enjoyable | ||

| Line 114: | Line 115: | ||

=== Facilitators to physical activity: === | === Facilitators to physical activity: === | ||

There are several facilitators to physical activity and active living that can help to overcome the perceived barriers as listed below | There are several facilitators to physical activity and active living that can help to overcome the perceived barriers as listed below <ref name=":10" /> <ref name=":11" /> <ref name=":12" /> <ref name=":13" /> <ref name=":14" />: | ||

1. Valued aspects of physical activity | 1. Valued aspects of physical activity | ||

Revision as of 10:32, 18 April 2018

Original Editors - Add your name/s here if you are the original editor/s of this page.

Top Contributors - Ronan Mac Cann, Lee Pettett, Sammy Anjum, Arden Metford, Kim Jackson, Lee Krol, Lucinda hampton, Rucha Gadgil, Rachael Lowe and Brian McGowan

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The physical and mental behaviour of today’s adolescent generation are determinants of their growth and development, now and throughout their lifespan [1] [2]. Technological advances of today’s society have contributed to sedentary lifestyles, causing young people to have an increased body weight and body mass index (BMI) than from one generation earlier[3]. The gradual increase of routine sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is a major contributor to chronic health conditions and is strongly correlated with the diagnosis of these diseases [4] [27SA]. This trend is at risk for continuing with today's young generation, as research suggests that the levels of physical activity decreases between the ages of 11-15 [IB5].Globally, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, causing 3.2- 5 million deaths annually [5] [6] [7]. While many of these chronic diseases are identified in adulthood, research suggests that the development of these conditions originate in childhood and adolescence [8] [9]. Furthermore, young people may have a less impressionable attitude towards their body image than adults, which may provide less resistance with behavioural change interventions [10] [11]. Therefore, the promotion of healthy behavioural habits must be learned during adolescent years, which will help carry forward the same behaviour into adulthood. Behaviours of active living established in early years can provide the greatest impact on maintaining these positive habits across one’s lifespan and influence mortality and longevity [12] [13].

What is the aim of this Wiki?[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists are well educated in interventions aimed at increasing levels of physical activity in young people. Research in the area of increasing PA is well established, however PA interventions aimed at maintaining an active lifestyle is an emerging area. Physiotherapists can therefore utilize this resource to facilitate and support active living behaviours in young people so that this behaviour is maintained into adulthood.

This Wiki resource incorporates a behavioural change framework that can be utilised for the larger young population, delivered in different community settings. This Wiki will focus on the ttm [[ref] of behaviour change, which categorises individuals into various stages, dependent on their physical activity levels. A modified questionnaire has been developed within this resource to assist practitioners in identifying which stage of the TTM the young population is in. This categorization is based upon the amounts of vigorous, moderate or walking activities performed within their last week. The physiotherapists can use this knowledge to identify and build upon the individuals’ or groups’ strengths to encourage them to maintain active living behaviour into adulthood.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

Upon completion of this resource the physiotherapist should be able to:

1. Define active living, describe the current issues/guidelines in young people and list all health implications.

2. Critically evaluate and synthesise behavioural change theory, strategies and the role of physiotherapists in the promotion of active living.

3. Competently implement all elements of the resource in an appropriate community setting for preventative health-related behaviour change in adolescents.

4. Reflect on learning and assess areas for further personal and community development.

How to use the resource pack[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here.

What is Active Living?[edit | edit source]

Active living is defined as a way of life that integrates physical and recreational activity into your everyday routine to encourage a healthier lifestyle [15]. These active routines include:

- Being active in outdoor parks, fitness centres

- Biking to work

- Walking to school

- Playing a recreational sport or game

- Activities of daily living

- Planned exercise sessions

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any movement carried out by a skeletal muscle that requires energy and ranges from low, moderate to vigorous PA with varying amounts of energy expenditure[16]. While, sedentary behaviour is defined as an individual who engages in prolonged sitting or lying positions without much movement [17]. Common sedentary behaviours includes TV viewing, video game playing, computer use (collectively termed “screen time”), driving automobiles and reading [17].

Physical Activity (PA) Guidelines:[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization’s physical activity guidelines to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular and bone health as well as metabolic health biomarkers for young people as shown in the Figure below [18].

Physical activity for young people in the context of family, school and community activities includes [19]:

- Play

- Games

- Sports

- Transportation – walking, bicycling, skateboarding and so on

- Chores

- Recreation and leisure activities

- Physical education or planned exercise

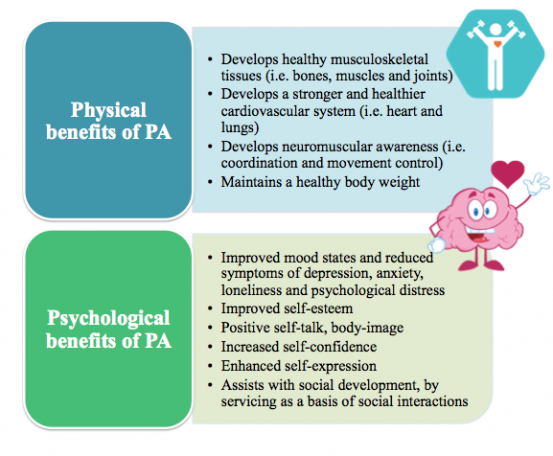

Benefits of physical activity in young people:[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology, physical activity and sedentary behaviour:[edit | edit source]

- Research suggests that on average 39% of adults in the UK are not physically active [20]. Physical inactivity causes 3.2-5 million global deaths annually and is the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality[5][21] [7].

- Sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity is strongly correlated to the diagnosis of many chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity [27 SA]

- Nearly half of the young population in the UK are sedentary apart from school activities [22] [23] [24]. Common sedentary activities include: screen-based sedentary behaviour, social sedentary behaviour, TV-viewing, homework and academics and lastly motorized transport[24].

- It is predicted that the 4.1 million children and young people who are obese and overweight globally are likely to remain obese and overweight into adulthood leading to greater risk of developing non-communal diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions at a younger age [21] [2]

- 13% of the youth aged between 11-15 year olds in England are not meeting the physical activity recommendations [23] [25].

- Increased sedentary behavior has been shown to greatly affect the health outcomes such as increased risk of obesity rates, lowered cardiorespiratory fitness and lowered insulin sensitivity in young people aged between 11-18 years old [26] [27] [28] [29]. However, alarmingly physical activity levels tend to drop off from ages 11-15 in most european countries [IB5]

Justification for the emerging role within Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

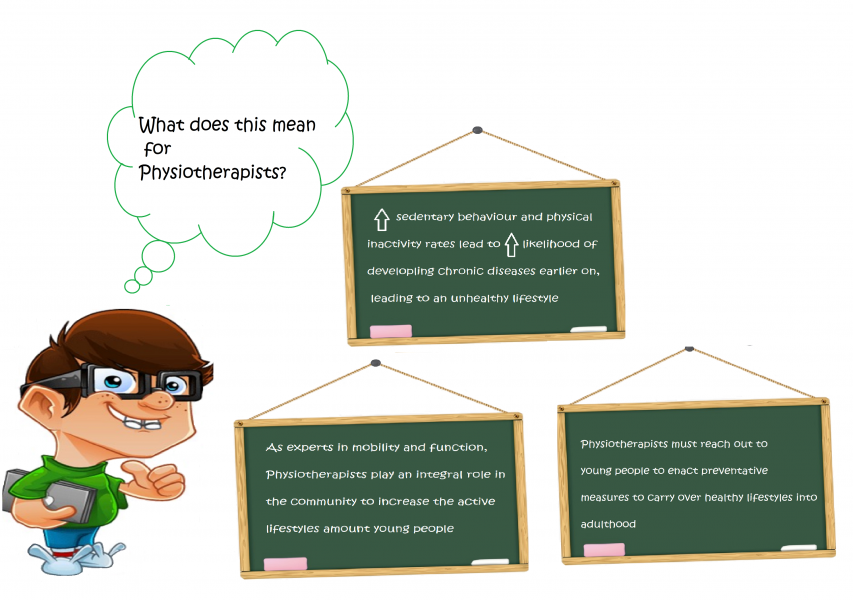

Physiotherapy is delivered in a variety of settings. Traditionally physiotherapists predominantly see the most of their clientele within a clinical setting on an individual basis (IB5). Good strategies and policy have been established in order to promote more active lifestyles within these settings. ‘Making Every Contact Count’ is a strategy introduced to help all organisations responsible for the health, wellbeing and care of the public to implement and deliver healthy messages systematically and encourage healthy lifestyles. (IB1)

If this strategy is actually carried out it has the opportunity to impact many people, with physiotherapy outpatient contacts alone numbering 3 million across the UK (IB2). This serves patients that attend clinics well as an active lifestyle is promoted to them. The issue is that this only targets the population that attend the clinic and follows a ‘don’t fix it if it’s not broken approach’ rather than a pro-active/preventative school of thought. It misses the large population who lead sedentary lifestyles but have no current health issues or have not attended a health professional’s appointment. There is also little known on the extent to which physiotherapists embed physical activity promotion in their routine care (IB2) and sparse evidence that it is comprehensively promoted in healthcare settings (IB3).

In order to increase physical activity worldwide it has been identified that a systems approach is required that focuses on populations and the complex interactions among the correlates of physical inactivity, rather than solely a behavioural science approach focusing on individuals (IB4). Healthcare is part of this system and within healthcare there is a need for organisational, environmental and individual approaches promoting active living. Future research needs to focus on how comprehensively active living is promoted within healthcare settings, however due to the limitations of reaching larger populations, other measures are additionally necessary.

As experts in movement and exercise, and with a thorough knowledge of functional anatomy and pathology and its effects on all systems, physiotherapists have specific competence and expertise and are ideally suited to promote, guide, prescribe and manage active living. Additional to promotion in their current settings waiting for the patients to come, In order to reach a larger population, physiotherapists need to immerse themselves more widely in the community to tackle sedentary lifestyles proactively and prevent their associated comorbidities.Physical education programmes at schools have been identified as an important tool to increase the awareness of health-enhancing physical activity (IB5). Evidence suggests the quality of such programmes is of importance for their outcome (IB6). With extensive knowledge of promoting, guiding, prescribing and managing physical activity for children with different needs, physiotherapists are excellent partners to develop, implement and follow-up high-quality physical education programmes in schools and community centres. This movement, additional to the individual patients seen will allow for a wider population to be targeted, which is paramount given the statistics relating to sedentary behaviour.

Economic implications of physical inactivity[edit | edit source]

Establishing routine physical activity as an adolescent is associated with an increased probability to continue this behaviour into adulthood and a reduced risk of disease [1]. However, with nearly half of young people aged 10-24 not achieving the recommended physical activity guidelines [18], the healthcare costs to communities and the NHS are under strain. In Scotland, physical inactivity causes 2500 deaths per year and costs the NHS £91 million per year [31]. In the UK, the levels of physical inactivity in young people will result in predicted diseases, decreased quality of life and reduced lifespan. The economic costs of these anticipated morbidities are estimated in Figure 5.

If the total number of young people meeting physical activity guidelines could increase by only 1%, the UK could save £0.8 billion. Figure 6 displays the viable economic savings associated with young people’s increase in physical activity.

Barriers and facilitators to physical activity:[edit | edit source]

Barriers to physical activity:[edit | edit source]

There are several barriers to physical activity and active living that are perceived by young people and parents, which varies from personal preferences, access to facilities and opportunities as shown below [32] [33] [34] [35] [36]:

- Preferences and Priorities:

- Sports or exercise is not enjoyable

- Negative body-image and physique

- Weak motor coordination and not suited for sports

- Potential shame/embarrassment of letting teams and oneself down

- Preference for other sedentary activities instead

2. Family life and parental support

- Parents’ lack of current participation in or enthusiasm for sports, exercise or other types of PA

3. Restricted Access to opportunities

- The cost in taking part in sports and activities

- Complexity and burden of organizing safe facilities

- Availability of local facilities

- Safety concerns

- Transportation advantages of cars for enabling quick and safe travelling

Facilitators to physical activity:[edit | edit source]

There are several facilitators to physical activity and active living that can help to overcome the perceived barriers as listed below [32] [33] [34] [35] [36]:

1. Valued aspects of physical activity

- Having fun and enjoying oneself

- Belonging to a sports team or group

- Afterschool program leisure activities

- Opportunities for spending time with family

- Keeping fit and health

- Ways of forgetting troubles

- Choice of sporting opportunity

2. Greater Access to opportunities and facilities

3. Afterschool programs to facilitate a greater level of physical activity with friends and serve as a basis of social interaction

4. Proper bicycle paths and sidewalks in neighbourhoods

5. Leisure Centres

Ethical considerations when working with young people[edit | edit source]

- Government Legislation and Policies For Working with Young People:

- Getting it Right for Every Child

- Ready to Act Plan

-Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014

- Safeguarding Young People

- Informed Consent

- Confidentiality

Knowledge and understanding of relevant legal frameworks, including local policies are essential for Physiotherapists who work with young people to ensure they work effectively and deliver services appropriately (LP 1).

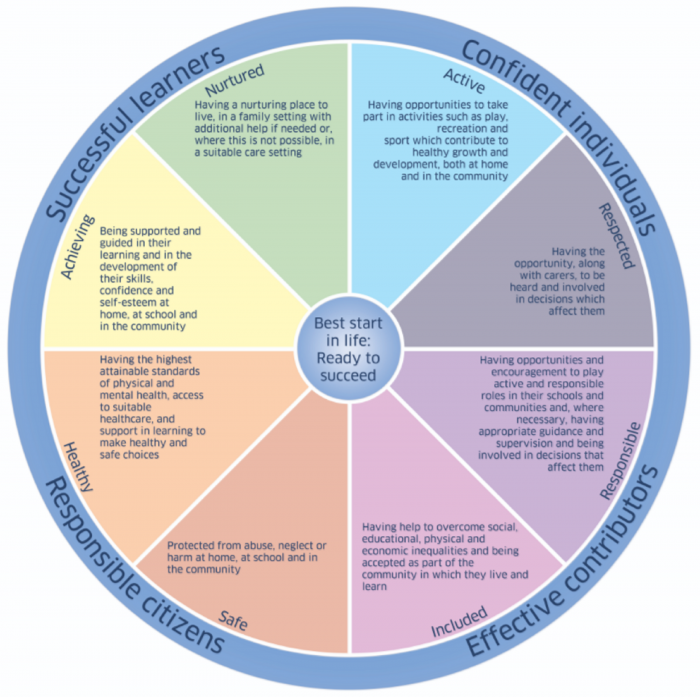

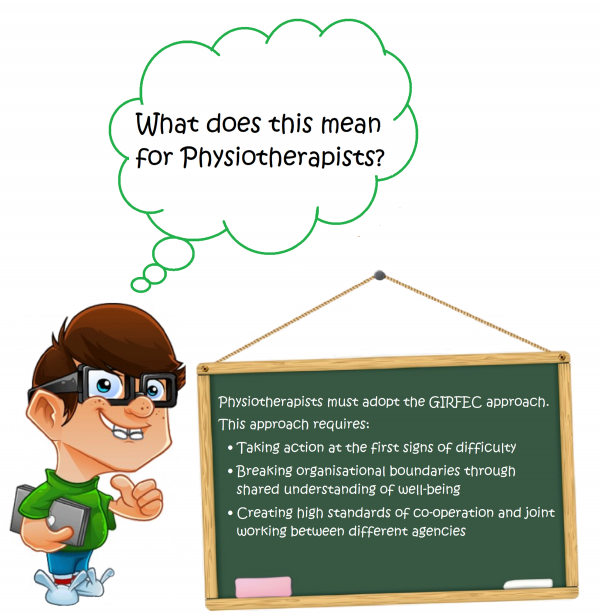

Getting it Right for Every Child

Central to the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5), is the ‘Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)’ policy (LP 6). This policy states that all adults working with children and young people should ensure their actions support the best interest of children and young people through promoting, supporting and safeguarding wellbeing and reporting on wellbeing outcomes (LP 10)

- GIRFEC is a key part of the Scottish Government’s commitment to addressing inequalities and improving outcomes for children and the young through early intervention and prevention (LP 11)

- GIRFEC is underpinned by the recognised need for shared principles and values and a common language among practitioners who provide services for children and families (LP 12).

- GIRFEC is intended to be used by health practitioners to gather information about a child’s well-being to identify concerns and determine what support and action may be needed (LP 10)

The GIRFEC approach:

- Integrated Working: focuses on children, young people, parents and services they need working together in a coordinated way to meet the specific needs and to improve overall well-being.

- Child Focused: ensures the child or young person (and their family) are at the centre of decision-making and have appropriate support available to them.

- Well-being of children: focuses on a child or young person’s overall well-being such as how safe, healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible and included.

- Early Interventions: focuses on tackling the needs of a child and young person early, aiming to ensure the needs are identified as early as possible to avoid larger concerns and problems to develop.

The well-being of children and young people is at the heart of GIRFEC (LP 11) The approach uses eight areas of well-being, SHANARRI indicators, which represent the basic requirements for all children and young people to grow and develop and reach their full potential. The eight indicators are illustrated in below in the well-being wheel of GIRFEC (LP 6).

Ready to Act Plan:

The Ready to Act Plan (LP2) delivers one of the actions from the AHP National Delivery Plan, where allied health professionals (AHPs) act as Agents of Change in Health and Social Care (LP 3). Ready to Act (LP2) will contribute to the developing Active and Independent Living Improvement Programme (LP 4). The plan sets out five key ambitions for AHP services for young people based on the outcomes young people, their parents, carers, families and stakeholders reported that mattered to their lives. The key ambitions are illustrated in the table below:

| Issue | Ambition |

|---|---|

| Participation and Engagement | Children's and young people's views will be asked for, listened to and acted upon to improve individual and environmental well-being outcomes and AHP services |

| Early Intervention and Protection | Every child and young person will have the best start in life, with AHP services using asset based approaches to aid prevention through universal services and supportive nurturing environments |

| Partnership and Integration | Children and young people, their parents, carers and families will have their well-being outcomes met at the most appropriate level through the creation of mutually beneficial, collaborative and supportive partnerships among and within organisations and communities |

| Access | All children and young people in Scotland will have access to AHP services as and when they need them at the appropriate level to meet their well-being needs, with services supporting self-resilience through consistent decision-making |

| Leadership and Quality Improvement | Children and young people, their parents, carers and families will experience services that are led by AHPs who are committed to a leadership and quality improvement approach that drives innovation and the delivery of high quality, responsive, child centred care |

The Ready to Act Plan (LP 2) is the first children and young people’s services plan in Scotland to focus on the support provided by AHPs. The plan sets the direction of travel for the design and delivery of AHP services to meet the well-being needs of young people. It is underpinned by the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5), the principles of Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) (LP 6) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (LP 7).

Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014:

The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5) establishes a legal framework within which services create new and dynamic partnerships to support young people, their parents, carers and families to achieve meaningful wellbeing outcomes (LP 1, LP8). These outcomes include what has come to be known as the SHANARRI indicators of well-being. AHPs, including Physiotherapists, play a key role in young people achieving well-being outcomes through developing their resilience and creating protective environments to enable participation and self-reliance (LP 9).

Safeguarding Young People:

Safeguarding is a term which is broader than ‘child protection’ and relates to the action taken to promote the welfare of children and protect them from harm (LP 1). Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility.

Safeguarding is defined in Working together to Safeguard Children 2015 (LP 13) as:

- Protecting children and young people from maltreatment

- preventing impairment of children’s and young people’s health and development

- Ensuring that children and young people grow up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care and

- Taking action to enable all children and young people to have the best outcomes

In order to safeguard and promote the welfare of children in Scotland, Physiotherapists should act in accordance with the following legislation and guidance:

- Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (LP 16)

- Protection from Abuse (Scotland) Act 2001 (LP 17)

- Protection of Children and Prevention of Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2005 (LP 18)

- Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007 (LP 19)

- Children and Young People (Scotland) 2014 (LP 5)

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NCPPC) (LP 20) offer links to the following documents for advice and guidance for health practitioners with concerns for children and young people:

- What to do if you’re worried a child is being abused: advice for practitioners (LP 21)

- Safeguarding children and young people from sexual exploitation (LP 22)

- Safeguarding children in whom illness is fabricated or induced (LP 23)

Informed Consent:

The position on consent in relation to children is complex (LP 20). It is important for Physiotherapists working with children to be familiar with literature, statutes, case law, professional guidance and department of health guidance on the ethical and legal aspects of children and young people’s consent (LP 1). The issue regarding capacity is of particular importance when dealing with children (LP 25). The law recognises broadly three stages of childhood with respect to consent:

- Children and young people who lack capacity: If the child does not have the capacity to give their own consent e.g. they are too young or do not understand fully what is involved, then a parent/ person with parental responsibility, or the Court, may give consent on the child’s behalf (LP 1)

- Children and young people with capacity: A child under 16 who has the capacity to make their own decisions may be referred to as ‘Gillick competent’ after the legal case that established children can make their own decisions in certain circumstances (LP 26).

- Children and young people over the age of 16: All 16-17 year olds with capacity are permitted by law to give their own consent to health interventions. (LP 27) Those children who are 16 or over on the date they attend for treatment do not need parental consent for Physiotherapy (LP 1). You should not share confidential information about 16-17 year olds with their parents, or others, unless you have specific permission to do so and/or you are legally obliged to.

According to Scottish law, children over the age of 12 are usually considered to be sufficiently mature to form a view and can have the legal capacity to consent to health interventions where in the opinion of a qualified health practitioner, the child is capable of understanding the nature and possible consequences of the intervention (LP 28)

This is a matter of clinical judgement and will depend on several things, including (LP 1):

- The age of the patient

- The maturity of the patient

- The complexity of the proposed intervention

- The likely outcome of the intervention

- The risks associated with the intervention

If the young person is not capable of understanding the nature of the healthcare intervention and its consequences, it is then advised to contact the child’s parent or guardian for consent to proceed with the intervention (LP 29). Although a young person is deemed capable of giving consent independently, it is still highly encouraged to seek consent from both the young person and their parents or guardians (LP 30; LP 31)

Confidentiality:

Confidentiality is of fundamental importance to young people as outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (LP 7). Young people have the same rights to confidentiality as adults, however the duty to safeguard young people should come first (LP 32, LP 33, LP 44). When obtaining consent, confidentiality needs to be explained to young people in terms that they understand and that they are aware of events in which the Physiotherapist may be required to act on concerning information and pass it on to relevant organisations (LP 36). In addition, parents of young people may request access to the young person’s responses after undertaking a health intervention questionnaire or survey. There are strong ethical reasons why parents should not have access to what their child says on a questionnaire as young children may be harmed, embarrassed or punished based on the responses they have given (LP 37). Rather than giving parents access to responses, it may be beneficial to offer parents to view the questionnaire prior to it being completed (LP37) or to encourage parents to initiate discussions about the questionnaire with their children in a home setting (LP 38).

Current government strategies[edit | edit source]

The Scottish government was one of the first countries in the world to release a national physical activity strategy, by providing a broad framework and implementation plan, called Lets makes Scotland more active in 2003. (LK 5)

This 20 year strategy’s five year review acknowledged there had been progress made with the populations physical activity levels. It has been followed up more recently after the 2014 commonwealth games with the strategy A more active Scotland. (LK 6) This is an adaptation of the Toronto Charter for Physical Activity (2010) which is a gold standard tool. (LK 7)

When specifically looking at young people, the strategies aim is to create a long lasting change in physical activity levels through:

Communities services and facilities:

- More children will have opportunities for active and outdoor play

- More children will routinely take part in play, sport, or other forms of active recreation

- More children will have opportunities for active and outdoor play

- Urban and rural environments will be designed to increase physical activity

- 20 mph zones will be widely introduced in residential and shopping areas

Schools:

- Education staff have the appropriate knowledge and skills to promote increased physical activity

- All places of learning can demonstrate the use of their estate and green space for physical activity

- All places of learning can demonstrate that pupils, students and staff have increased levels of physical activity

- More children and students use active travel to get to their places of learning

This was to be achieved through legacies where it was reported over 50 had been launched at their in 2015 review. Legacies are part of the implementation plan, an example includes is a national week was held encouraging more women and girls into sport as females have been found to be less active than males (LK 8). The statistics also show young peoples physical activity have slightly increased both including and excluding the increased physical activity in schools. It is still, however, unclear the prevalence rate transferring onto a long-term active lifestyle as the adult physical activity level has not increased.

Health-Related Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Behaviour change involves influencing health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours and should be targeted at an individual, household, population or community (RMC1). With an ever-changing health system, it is widely believed that by addressing problem behaviours early this can have an impact on the development of co-morbidities and mortality in later life which influences quality of life (RMC1; RMC2). In addition, these healthy changes reduce the risk of preventable diseases which place a huge economic burden on our health-system (RMC2). The literature in this area has been growing exponentially in recent years with the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (RMC3) and many academic researchers producing evidence-based guidance for health professionals. In their latest corporate strategy (2017-2020) (RMC4) for physiotherapy, the CSP have acknowledged the role physiotherapists will play in empowering individuals in communities to take control of their own lives to stay healthy for longer. This will involve physiotherapists using expert knowledge in human movement and health promotion to implement effective health-related behavioural change strategies in a preventative way among different populations. One of the fundamental problems with behaviour change however is indeed its application into practice. How does one change the habitual behaviours of individuals/groups? What strategies/interventions can be used? How do you maintain this healthy lifestyle?

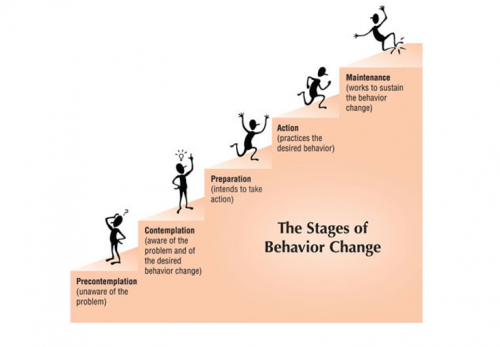

Based on the science of behaviour a large amount of literature has been published examining the effectiveness of several behaviour change models. These models have been developed to conceptualise the overwhelming amount and complexity of behavioural change theory and to help our understanding of the dynamic interrelationships that are necessary for sustained active living. With the use of these model’s health professionals can systematically implement change. They are broken down into the following: Social-Cognitive theory, Belief /Attitude theories (Theory of Planned Behaviour), Competence-based theories (Self-Efficacy Theory), Control-based theories (Self-Determination Theory), Stage-based theories (Transtheoretical Model) and other hybrid models (RMC5). Although there is a vast array of theory to choose from, the stage-based model (Transtheoretical model-TTM) is arguably the most commonly used in behaviour change. The following section will focus on the TTM and how this framework can be used in the process of behaviour change.

Models of behaviour change[edit | edit source]

Transtheoretical Model

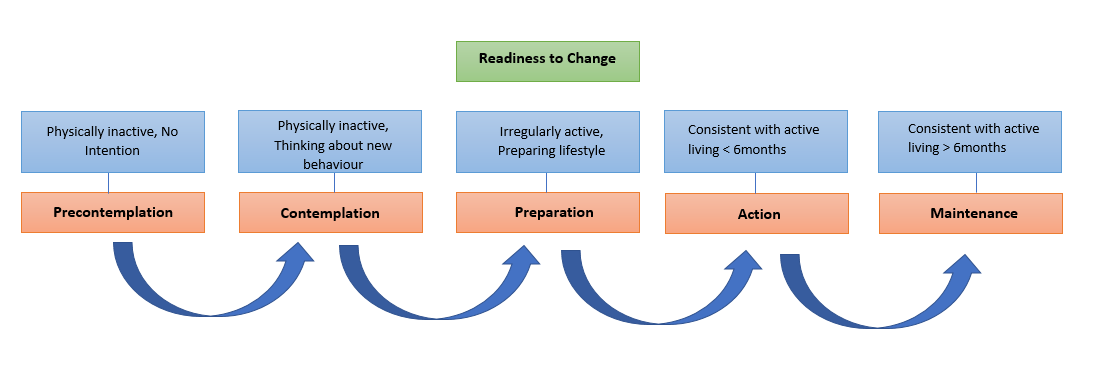

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM), first proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) (RMC6), is a process-oriented framework for understanding and implementing effective health behaviour change (RMC7). This model brings together many psychotherapy theories in one concise framework to establish a person/groups ‘readiness to change’ (Biopsychosocial) (RMC8; RMC7; RMC9). As Marcus and Forsyth (2003) (RMC10) wrote, quite often “physical readiness is not likely to be the main barrier to activity; rather it is the psychological readiness to change”. Due to the heterogeneity of humans, many people have different readiness to change and therefore require interventions that reflect the natural cycles of health-related behaviour change. The fundamental purpose of the TTM is to systematically affect lifelong active living and it describes when and how people change (RMC6).

The TTM encompasses over fourteen constructs (RMC11) which several authors (RMC 12; RMC13; RMC14) have divided into three sections:

1. Stages of Change (SOC)

2. Independent variables (Processes of Change).

3. Dependent variables (Decisional Balance; Self-Efficacy)

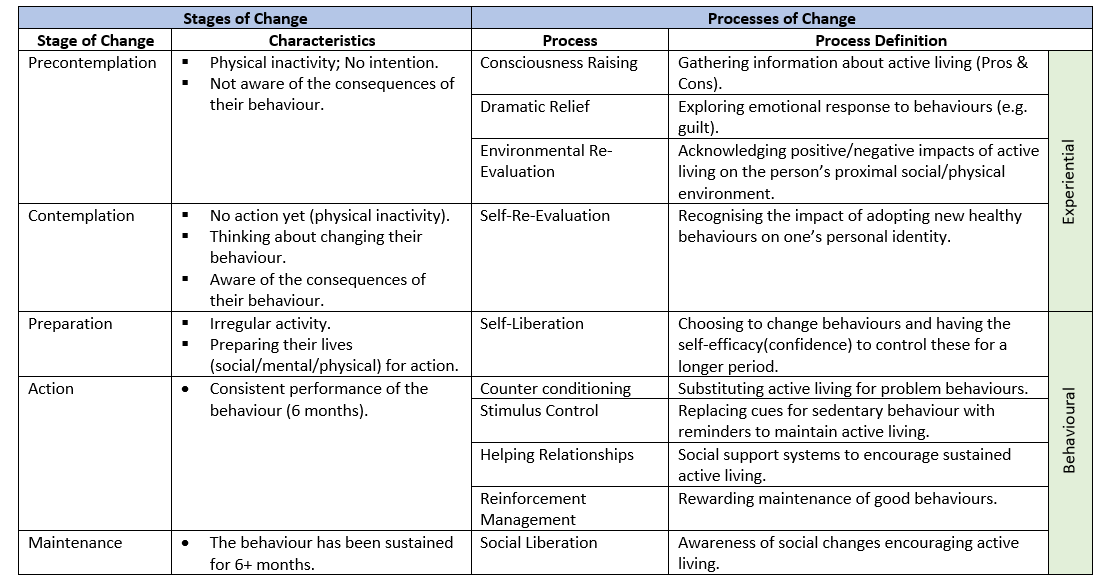

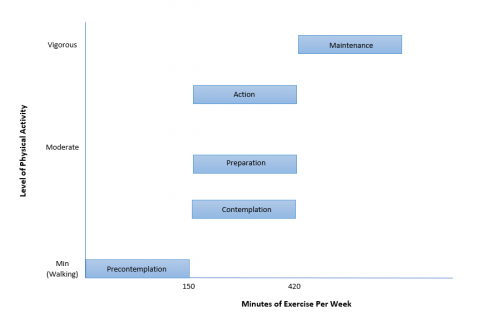

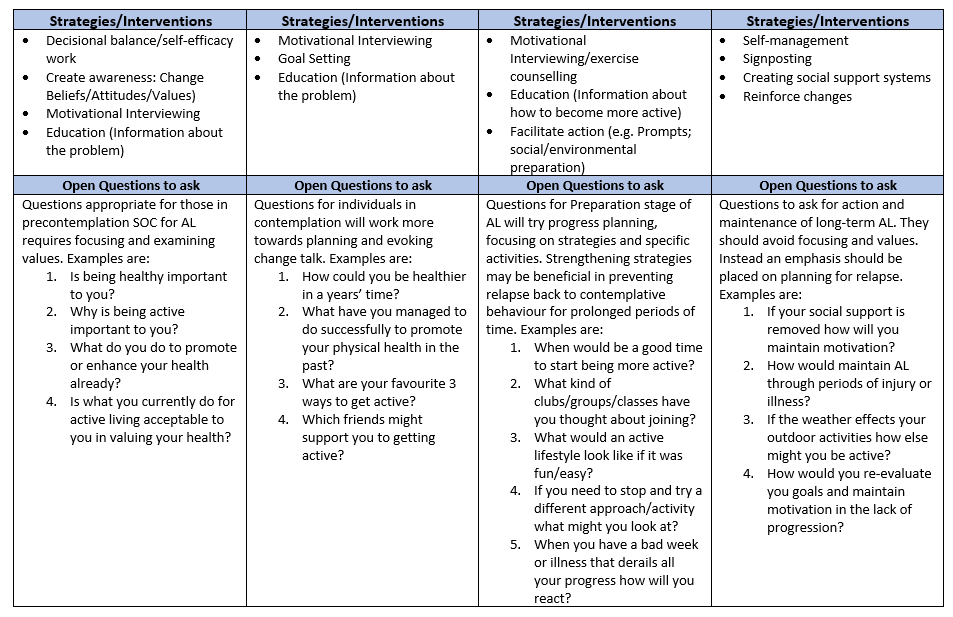

There are five stages of change in the TTM (Table ??) which categorizes people based on how active they are. In the first stage, precontemplation, individuals are not participating in any activity nor do they have any intention to change these habits. As they are unaware of the consequences of their behaviours much of the work in this stage should focus on motivational interviewing, decisional balance/self-efficacy work (education). In the contemplation stage, individuals are still not active, but they are more aware of the benefits of changing their behaviour and are beginning to think about how to change. The preparation stage involves irregular activity as the individuals begin to prepare their lives for change within the next month (RMC15). Once individuals are consistently active they are said to be in the action stage. It is at this point that the probability of relapse is highest and therefore it is vitally important for individuals to take advantage of any opportunities to maintain their new healthy behaviours. The final stage of the TTM is the maintenance stage and this is ultimately the end goal of an intervention. Individuals who are at this stage must be consistently performing their new behaviours for at least six months. The stages of change are often described as a cyclical process as individuals jump between stages as they progress (RMC9).

The Processes of change are concerned with ‘how’ individuals change (RMC9; RMC13). There are ten processes of change (Table ??) and the choice of the most appropriate strategy is based on the stage of change that the individuals are in. Once a SOC has been established physiotherapists can use the processes of change to design appropriate interventions/strategies for effective behaviour change. At a higher order structure these processes are sub-divided into experiential (cognitive-affective) and behavioural processes (RMC15). In their study Romain and colleagues (2018) (RMC11) propose that public health interventions should use a combination of experiential and behavioural processes of change to achieve moderate physical activity levels and sustained active living among individuals. The first five processes are experiential and are concerned with thinking about an activity/new behaviour whereas the last five are behavioural processes which involve action (RMC16).

[Adapted from ??]

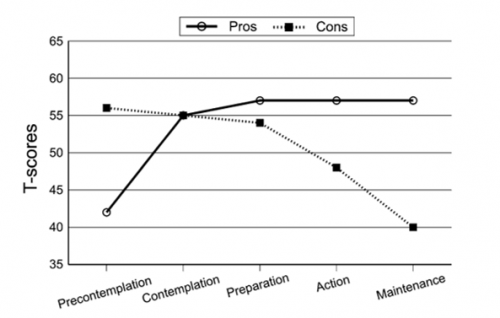

Decisional balance, first proposed by Janis and Mann (1977) (RMC17), is one of the core constructs for progression through the TTM. It is concerned with the pros (perceived advantages) and cons (perceived disadvantages) of changing behaviour (RMC18). Several studies have shown a strong relationship between decisional balance and an individual’s readiness to increase physical activity (RMC19; RMC20). As individuals move through the SOC from precontemplation to maintenance the balance shifts in favour of the pros of changing behaviour (Figure ??). Interestingly in the contemplation stage the pros and cons are of equal weight which may leave individuals ambivalent to change. It can be argued that an emphasis should be placed on education and motivational interviewing at these stages to increase adherence and decrease opposition (RMC21). This will be discussed in greater detail in later section.

[Adapted from RMC18]

Self-efficacy, first proposed by Bandura and colleagues (1977) (RMC24), can be defined as “an individuals belief in his or her ability to perform a specific action required to attain a desired outcome” (RMC26 p. 176). Self-efficacy is part of social-cognitive theory and a key construct of the TTM. Young people with high PA self-efficacy typically participate in activity for longer periods of time and therefore it is vitally important for sustained active living. With a higher self-efficacy, individuals try harder to achieve their goals, can conquer barriers and set-backs and will look to maintain their healthy behaviours throughout life (RMC26). This personal component can be improved throughout health-behaviour change as individuals progress through the SOC. In the early SOC the self-efficacy to participate in physical activity is outweighed by the temptations to stay physically inactive. Individuals are said to lack the confidence in themselves to change their behaviours. Work is required through education and support /guidance to increase this self-esteem. In the later stages of health-behaviour change social support systems become more important as individuals look to maintain this new active lifestyle. The probability of relapse in this population is quite high due to other social factors that may come into play at this age. Studies have shown decreases of 7% in PA in young people (11-18year olds) each year (RMC29) with an estimated 60-70% decline globally as they transition into adulthood. Self-efficacy and social support have been widely acknowledged as key determinants of PA (RMC25) and it is hypothesized that these components work interchangeably during adolescence (RMC26; RMC27; RMC28) to prevent relapse. If an adolescent’s self-efficacy is low, social support systems may compensate (RMC26). At this age peer support becomes more important as adolescents move away from the comforts of parental support.

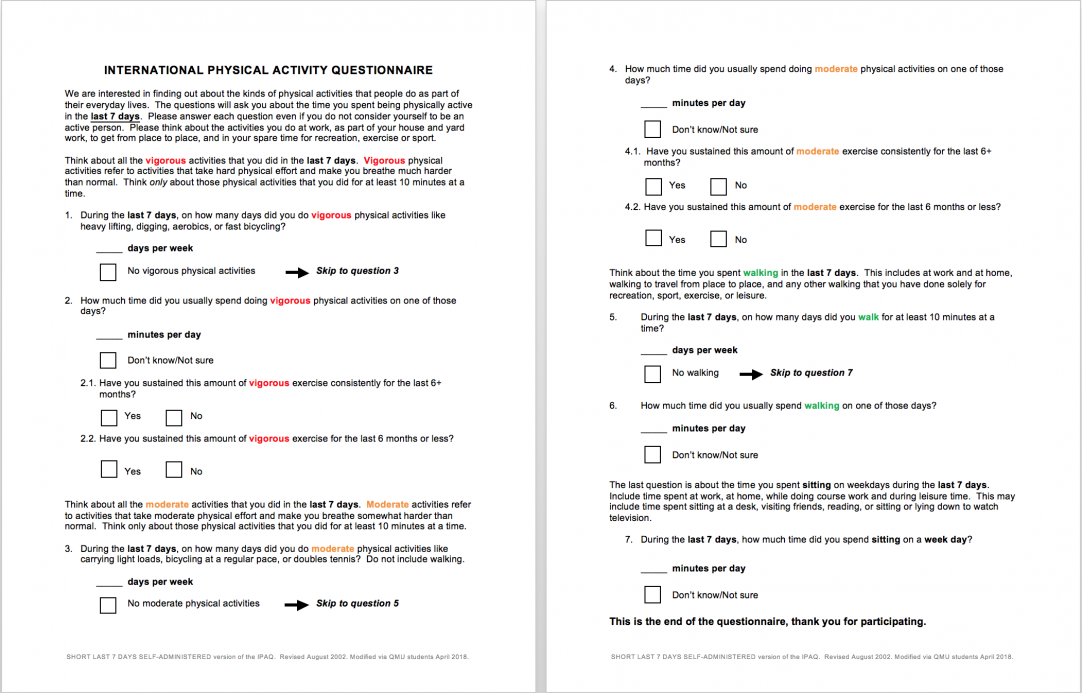

Proposed questionnaire for measuring physical activity[edit | edit source]

The following questionnaire is a modified version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF), comprisising of seven questions. The aim of this questionnaire is to assist in identifying which stage of the transteoretical model the adolescent participants are in. After the total minutes of vigorous, moderate or walking activites performed over the participant's last seven days have been calculated, the physiotherapist can utilise the marking scheme provided in table ----- to establish which stage of the transtheoretical model the participant is in. Although this modified IPAQ-SF is answered on an individual basis, this questionnaire may be administered in group community settings, resulting in small groups of participants allocated into their individual stages of behaviour change.

There is conflicting evidence for this assessment in adults, a large study investigating the reliability and validity in 12 countries found the instrument acceptable and as good as other questionnaires (LK 1). In contrast a systematic review found the IPAQ-SF typically overestimated physical activity and concluded as a weak measure (LK 2). The evidence is more robust with adolescents, as a significant correlation was found between the questionnaire and moderate vigorous physical activity recorded on an accelerometer however physical activity and sedentary time were both under reported (LK 3). Another study investigating adolescents also found the reproducibility and validity of the IPAQ-SF as an acceptable measurement for measuring physical activity (LK 4)

Modifications to the original IPAQ-SF (ref---) were performed by QMU students in April 2018. Alterations included asking the participant to record the total "minutes per day" of activities performed and excluding "hours per day". This was done on the basis that physical activity guidelines are calculated in minutes, not hours (ref-----), therefore simplifying the marking process for the physiotherapist, especially when fast calculation of multiple questionnaires are required. Additionally, questions 2.1, 2.2, 4.1 and 4.2 were added to facilitate a simple "yes" or "no" criteria for the scoring into the "maintenance" or "action" stages in the transtheoretical model.

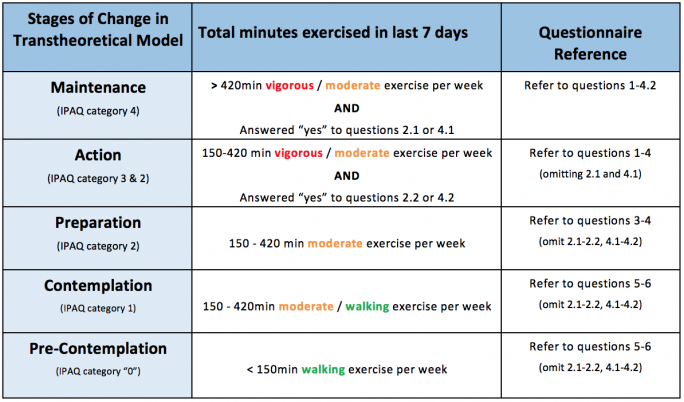

Modified IPAQ-SF Scoring System into the Transtheoretical Model[edit | edit source]

The following table depicts the marking criteria for the identification of behavioural change stages in the transtheoretical model.

Instructions on determining the stage of behaviour change:

- Calculate total number of minutes exercised in the last 7 days for vigorous, moderate and walking intensities.

- Using the chart above, classify the participant into the corresponding Transtheoretical Stage of Change using the total number of minutes exercised in accordance to level of intensity.

- Please note that the participant may be placed into the “maintenance” or “action” phase if they answered yes to corresponding questions 2.1-2.2 or 4.1-4.2.

Behavioural Change Progression[edit | edit source]

Strategies/interventions to promote active living[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing (MI)[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a technique for helping people to change their desired behaviour. MI can be defined as “ a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change”. (1BM)

Ambivalence is having two thoughts about a behavior or change. This is at the heart of MI framework. (1&2 BM) This ambivalence can be a barrier to progressing through the TTM. A skilled therapist can use MI processes to progress patients through the stages of the TTM to the stage of action while increasing autonomy and resilience to relapse through partnership with the patient. This requires open questions and reflection/problem solving skills from both patient and therapist. The Patient centered approach is incorporated in MI and is well represented from this quote:

‘’Our service exists to benefit the people we serve (and not visa versa) The needs of the clients have priority.’’ (1 p.22 BM)

The skills of the therapist elicit either change talk (talk favoring new behaviour) or sustain talk (talk about staying the same with the status quo). The difference between MI and other uses of TTM is in MI the therapist doesn’t remove the barriers or give coping strategies/ information without it being asked for. Instead the therapist tries to help evoke more change talk and the patient's own motivations and planning skills to implement the changes. Slowly ambivalence is reduced with more change talk, planning and increased self efficacy. (1BM)

The 4 processes and sample questions for MI are:

- Engaging- Why would you want to make this change? Would not adopting active living make you happier in 1 years time?

- Focusing- How might you go about it in order to succeed? How have you succeeded with active living in the past? What makes it easier to do more active living?

- Evoking - What are the three best reasons for you to do it? How important is this change? What will it feel like to have not changed active living behaviour in 1 years time?

- Planning-What would this look like if it was easy/fun? How can active living be supported by friends/family/other?

Overlap can occur when asking questions in this process. When patients are coming to us for advice it is easier to get into focusing and engaging. As we go out to the community it can become much more difficult. Clearly the 4 proccesses align with the TTM with Engaging being the initial pre contemplative to contemplative and focusing, evoking and planning all moving the behavior towards preparation, action and maintenance (1BM).

Importantly MI is not advocated or advised for those in action and maintenance phases as it may evoke resilience and relapse accidentally. Caution should be made in questioning the motives/values of someone already displaying an active lifestyle (BM1)

A good MI therapist will flow between the 3 styles Directing- Guiding- Following.

| Directing examples | Guiding examples | Following examples |

| Lecturing, arguing for change, giving one's own experiences as a solution, giving facts and tips unsolicited. | Open questions, active listening, affirming good behaviours/motives/values and reflecting on what has been achieved/agreed upon as change goals. | Listening, PCC, allowing patients to lead the conversation and set the change goals and accepting the patient as they are not how they should be. |

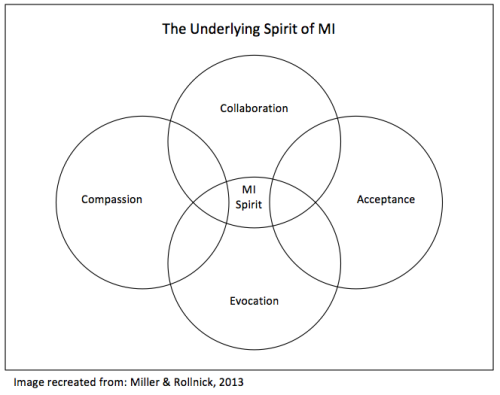

MI goes against the idea of expert and patient and is concentrated on partnership and

collaboration. Avoidance of preaching and lecturing or giving unsolicited advice this can cause opposition despite the therapist's best intentions for their client.

This can be called the righting reflex and counterintuitively if we give the answers to clients unsolicited they oppose them. Opposition, conflict and sustain talk are all to be avoided by the therapist.

Spirit of MI (picture)

The MI spirit has been newly added to their latest book and MI courses when they realised it was not being used with compassion and more as a therapist vs patient wrestle vs collaborative partnership with the hearts desires of the patient at the centre of the process.

The key tools in MI are open questions, affirmations, reflective listening and summarizing (OARS). These are covered in detail by Miller and Rollnick (2013) (1BM) for ease of this wiki we will look at some useful open questions which may help the clients to reflect and move past ambivalence and thus through the stages of change (1,4 BM). A quote from (1) that shows why having open questions answered by the client may be most successful is:

‘People are generally better persuaded by the reasons they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the minds of others. -Blaise Pascal ‘ (1BM p25). Examples are displayed in table xyz

Justification for MI in AL with adolescents:

Grays and steele (2014) concluded from their meta-analysis of MI in pediatric behavioural change that MI is effective in promoting healthy behavioural change and is most effective when done with both parent and child. Controversially they do not conclude that number of sessions or skill of MI practitioner are indicative of successful interventions. They also advocate for matching cultural background of MI practitioner to that of the clients while noting this still needs to be researched. A study by Hardcastle et al (2012) (6BM) not included in the 70+ papers shows a dose response to MI with 4+ sessions delivered having the most significant influence on increased effect size. She also attributes the greater effect sizes seen in this study than others with the increased MI training of 6 vs 3 days seen in other studies. This newer research not included in Miller and Rollnicks newest version of MI textbook refutes the idea that the skills most important to MI therapists is empathy which shows the best results in sustaining long term change irrelevant of number of sessions and education of therapist due to the dose response (1,6 BM). However their therapists may have had higher empathy skills due to the greater level of MI training and longer time practicing MI (1BM). Interestingly the long term effect at 2 year follow up for MI in children in Italy showed no effect of MI on PA or obesity after 5 sessions spaced out at 0, 1, 4, 7, and 12 months(7BM) they concluded by recommending booster sessions after 1 year not addressing the potential that 1 inisial session followed by a 1 month gap may not have been sufficient at the start of the study.

Having Physiotherapists trained well in and implementing MI and the skills associated with it may be hugely effective in maximizing behavioral change for adolescents and their families. Having 4 sessions and a booster session may be most appropriate. The most valuable skill in MI for the therapist is reflective listening. Using the questionnaire provided and other clinical reasoning skills will help to focus the open questions to where the adolescent is at with regard to TTM. Furthermore physiotherapists skilled in MI and trained in its education may teach it to other health care workers, pe teachers and coaches to aid them in helping adolescents to have more active lifestyles. Training and advancement in MI is common in the NHS and other organisations do inservices on MI see link

Mobile Apps:[edit | edit source]

Given that many young people constantly use mobile phones on a daily basis, mobile phones can be a viable tool to promote an active lifestyle and deliver positive health interventions (LP49). Mobile Apps can be selected according to individual needs of the participant and can be a fun, interactive, cost-effective and social platform to encourage a more active lifestyle (LP 50). Apps can enable users to set targets, enhance self‐monitoring, and increase awareness (LP51).

There are vast amounts of different mobile apps available that focus on healthy living and physical activity, however the below list is a small selection of free apps that may be helpful to promote an active lifestyle:

- Active 10 Walker: An NHS approved app for people looking for easy ways to add activity to their day and improve their health by getting into the habit of walking briskly for 10 minutes every day.

- Couch to 5k: An NHS approved app designed to get people off the couch and running 5km in 9 weeks.

- Dungeon Runner Fitness Quest: The user progresses through the game by fighting enemies with punches, opening secret passages with squats and avoiding traps with ski-jumps. This app incorporates motion-tracked exercises through the gram to encourage physical activity.

- Rise & Recharge: Developed to help reduce sitting time and encourage regular movement.

- Geocaching ®: Geocaching is a real-world, outdoor treasure hunting game using GPS-enabled devices. Participants navigate to a specific set of GPS coordinates and then attempt to find a container hidden at that location.

- Zombies, Run! 5 K Training: A training program, with a series of missions , whereby the user runs and listens to various audio narrations to collect virtual supplies and gets fit to escape the zombies.

- Charity Miles: Earn money for charities every time you run, walk, or bicycle. Corporate sponsors agree to donate a few pennies for every mile you complete.

- Fitnett: An abundance of five to seven-minute targeted workouts. The app also incorporates the phone’s camera to measure how closely the participant follows the moves on the screen.

- Pokémon Go: Encourages people to get off the couch and become more active by exploring the outside world. Participants complete a variety of objectives with the opportunity to earn rewards and discover various Pokémon.

- Ingress: Transforms the real world into a landscape for a global game of mystery, intrigue, and competition. The app encourages users to get off the couch and become active by trying to complete objectives and take over hack points.

- Sworkit: A number of built-in exercise regimens, including yoga, that simply gets people moving all the way up to 60 minute work-outs. The work outs can be personalised with over 160 exercises.

- Personal Fitness Coach: Contains hundreds of workouts from professional trainers that guide, motivate and keep the participant company along their journey.

- Strava: Tracks running and riding with GPS, offers options to join challenges, share photos from activities and follow friends activities.

- Global Yoga Academy: Offers classes from 5 to 60 minutes in duration from beginner to advanced levels.

== Conclusion ==

Add your content to this page here!

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005 Apr 1;28(3):267-73.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Obesity and overweight reports [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- ↑ Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):483-90.

- ↑ Hills AP, King NA, Armstrong TP. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents. Sports medicine. 2007 Jun 1;37(6):533-45.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, Van Mechelen W, Pratt M, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1311-24.

- ↑ Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 World Health organization WHO. Global Health Risks-Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Cancer. 2017 Feb 3.

- ↑ Hallal PC, Victora CG, Azevedo MR, Wells JC. Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports medicine. 2006 Dec 1;36(12):1019-30.

- ↑ Halfon N, Verhoef PA, Kuo AA. Childhood antecedents to adult cardiovascular disease. Pediatrics in Review. 2012 Feb;33(2):51-60.

- ↑ Beckman H, Hawley S, Bishop T. Application of theory-based health behavior change techniques to the prevention of obesity in children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006 Aug 1;21(4):266-75.

- ↑ Kater KJ, Rohwer J, Levine MP. An elementary school project for developing healthy body image and reducing risk factors for unhealthy and disordered eating. Eating Disorders. 2000 Mar 1;8(1):3-16.

- ↑ Paffenbarger Jr RS, Hyde R, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. New England journal of medicine. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):605-13.

- ↑ Harold W. Kohl, I., Cook, H., Environment, C., Board, F. and Medicine, I. (2018). Physical Activity and Physical Education: Relationship to Growth, Development, and Health. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201497/\ [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Active Living [Internet]. Healthy Alberta. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20120403195030/http://www.he

- ↑ What is active living. [Internet]. ACTIVE LIVING RESEARCH GROUP. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://www.activelivingresearch.org/active-living-topics

- ↑ What is moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity. [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2014 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www. who. int/dietphysicalactivity/physical_activity_intensity/en

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, Chastin SF, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJ. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)–terminology consensus project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017 Dec;14(1):75.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Physical activity in children and young people [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2011 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/

- ↑ Physical Inactivity Report 2017 [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2017 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.

- ↑ Physical activity statistics [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2015 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-activity-statistics-2015

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Scholes S, Mindell J. Health Survey for England 2012: Physical activity in children. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre. 2013.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Arundell L, Fletcher E, Salmon J, Veitch J, Hinkley T. A systematic review of the prevalence of sedentary behavior during the after-school period among children aged 5-18 years. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2016 Dec;13(1):93.

- ↑ Streetgames.org. (2014). [online] Available at: https://www.streetgames.org/sites/default/files/The-Inactivity-TimeBomb-StreetGames-Cebr-report-April-2014.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Mitchell JA, Byun W. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes in children and adolescents. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2014 May;8(3):173-99.

- ↑ Boreham C, Riddoch C. The physical activity, fitness and health of children. Journal of sports sciences. 2001 Jan 1;19(12):915-29.

- ↑ Malina RM. Physical fitness of children and adolescents in the United States: status and secular change. InPediatric Fitness 2007 Jan 1;50:67-90.

- ↑ Steele RM, Brage S, Corder K, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome in youth. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2008 Jul;105(1):342-51.

- ↑ Nike (2013). Designed to Move: A Physical Activity Action Agenda™. [image] Available at: https://clubs.marathonkids.org/keeping-kids-moving/ [Accessed 17 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Beta.gov.scot. (2018). Physical activity and sport - gov.scot. [online] Available at: https://beta.gov.scot/policies/physical-activity-sport/ [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Wright A, Roberts R, Bowman G, Crettenden A. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disability and rehabilitation. 2018 Jan 30:1-9.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Brunton G, Harden A, Rees R, Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Oakley A. Children and physical activity: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Martins J, Marques A, Sarmento H, Carreiro da Costa F. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health education research. 2015 Aug 31;30(5):742-55.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status?. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2003 Apr 1;25(2):100-4.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Eyre EL, Duncan MJ, Birch SL, Cox VM. Low socio-economic environmental determinants of children's physical activity in Coventry, UK: A Qualitative study in parents. Preventive medicine reports. 2014 Jan 1;1:32-42.