Primary Lateral Sclerosis (PLS): A Case Study

ABSTRACT[edit | edit source]

This fictional case study

INTRODUCTION[edit | edit source]

Primary Lateral Sclerosis (PLS) is a rare, idiopathic progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the upper motor neurons (UMN) [1][2]. Further, degeneration of the motor cortex and corticospinal tracts will ensue with no loss of lower motor neurons (LMN) or disruption to the anterior horn cells [3][4][5][6]. While the clinical presentation of PLS is very similar to that of ALS, PLS affects only the UMNs while ALS affects both the UMNs and LMNs [1][2][6]. As a result, this often leads to PLS being misdiagnosed as ALS [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. In comparison to ALS, the prognosis of PLS is considered to cause less harm as it is not fatal in most cases [1] [2]. A confirmed diagnosis of PLS can only occur many years later when it is confirmed that there is no LMN disruption [3][4][5][6][7]. There is currently not a lot of succinct research surrounding PLS as it is not only similar to ALS but a lot of other neurological conditions as well [2].

Previous case studies found that the clinical signs and symptoms of PLS had to be present, on average, for a minimum of three to five years to conclude a definite diagnosis [3][4][5][6][7]. Additionally, those with PLS rarely have a family history of it [1][2][7]. PLS is a slowly progressive disease that presents more commonly in males than females [3][4][5][6][7]. The onset of the disease usually occurs between 40 to 60 years of age, with 50 to 55 years of age being the average age in most samples studied [1][3][4][5][6][7].

PLS is characterized by progressive weakness and stiffness involuntary muscles that typically emerge first in the lower extremity. The disease may then progress to the trunk, followed by the upper extremity, and lastly to the corticobulbar tract and can typically cause a pseudobulbar affect (emotional lability) [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. In addition, patients may also experience dysarthria (difficulty speaking) and dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. In a case study by Wais et al. (2016), they found that very few patients displayed symmetrical distribution of symptoms [7]. Some patients may undergo latent periods where symptoms seem to subside slightly to allow for more normal functioning [3][4][6]. Typical signs and symptoms that patients reported included: weakness, clumsiness, hyperreflexia, increased muscle tone (spasticity), and increased urinary urgency. However, the first sign that patients typically described as a disruption in the smoothness of their gait cycle [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Patients with comorbidities may present with some signs and symptoms that are not of the typical clinical presentation of PLS, including: sensory symptoms and LMN degeneration such as muscle atrophy, fasciculations, decreased reflexes, or tone [2][3]. Most patients will experience a slow spread of symptoms over many years before plateauing indicating a better prognosis and more independent life than ALS [1][2]. Death is typically as a result of bulbar dysfunction, malnutrition, or breathing decline [4][6].

With respect to the fictional case study of Mr. Parker, the main challenge experienced during the physiotherapy sessions was managing his sporadic emotional outbursts. This presentation aligns with the emotional lability characteristic of PLS. While these outbursts do not happen often, it does take some time to refocus the session back to the activities that were being performed prior.

The purpose of this fictional case study is to provide a brief overview of what physiotherapy care may involve in an out-patient setting with respect to the assessment and management of an individual in the early stages of PLS. Further, we will discuss the role of physiotherapy in the management and maintenance or adaptation of function associated with PLS. There is currently limited research on such a topic, which is why this fictional case study aims to provide some framework for just that.

CLIENT CHARACTERISTICS[edit | edit source]

Mr. Parker is a retired 56-year-old male, right-hand dominant, who presents with early-stage PLS. Until about three years ago (2019), he was an avid CrossFitter, participated in leisure activities with his two granddaughters, and worked part-time at his family-owned construction company. Previously, he would train at the gym 2-3 times per week and would go on 3-5 km runs twice a week. Mr. Parker first presented to his family physician three years ago with reports of weakness in his legs that had progressed over time to cause clumsiness and stiffness during his runs. He reported that he “had to stop running because of a fear of falling”. He was then diagnosed with ALS in 2019 through subjective history, physical examination, and diagnostic tools (MRI and EMG). However, upon a recent reassessment in 2022, the neurologist concluded that Mr. Parker has PLS as his symptoms did not progress to the LMNs - as concluded by a secondary physical examination and diagnostic tools. Mr. Parker’s neurologist initially referred him to physiotherapy in 2019 following his ALS diagnosis. However, he still recommends that Mr. Parker continues with his rehabilitation following his PLS diagnosis for maintenance purposes.

Since the initial diagnosis of ALS, Mr. Parker's health status has slowly deteriorated. Mr. Parker was prescribed a single-point cane with a 2-point step-through pattern by his previous physiotherapist in 2019, which he uses on occasion.

In 2020, he was forced into an earlier retirement than planned as he was unable to keep up with the part-time hours and work duties at the construction company. Furthermore, he is now unable to participate in any recreational running or CrossFit training due to the severity and worsening of his symptoms. He has now adjusted his fitness regime and uses resistance bands to work out from time to time at home and tries to go for daily walks with his wife totaling 10-30 minutes. His home activities have also been reduced due to decreased activity tolerance, decreased endurance, and fatigue. Therefore, his wife has taken on more responsibilities at home.

Upon reassessment in 2022, Mr. Parker reports that he is starting to experience swallowing difficulties and painful spastic posturing in his left arm. Overall, his condition continues to remain relatively the same since the initial onset but has since started to consistently take medication (Lexapro) for his concurrent depression. Additionally, his wife describes that he has been having intermittent, uncharacteristic behavioral outbursts as of two months ago.

EXAMINATION FINDINGS[edit | edit source]

Subjective[edit | edit source]

Patient Profile[edit | edit source]

- Date of Birth (DOB): May 9, 1966 (56 years old)

- Gender: Male

- Hand Dominance: Right-hand dominant

- Significant Presentation: PLS (misdiagnosed as ALS three years ago)

History of Present Illness[edit | edit source]

Insidious onset of bilateral leg weakness and stiffness which Mr. Parker noticed during his daily runs 3 years ago. Symptoms developed to include painful spastic posturing in the left arm, difficulty balancing/ clumsiness, intermittent dysphagia, and generalized fatigue. Had experienced several falls over the last few years due to poor balance control during ambulation. Developed a fear of falling that has greatly limited his participation in work, leisure activities, and general ambulation. He discussed his onset of symptoms with his family physician, who referred him to a neurologist in Toronto. He was initially diagnosed with ALS about 3 years ago (2019) by his neurologist, who then updated the diagnosis to PLS about 5 weeks ago after reassessment.

Pain: Describes intermittent, sharp pain isolated to the left arm, which refers down the shoulder to the elbow distally. The onset of pain occurs during elbow flexion ROM. Reports pain 6/10 with movement and 0/10 at rest. Takes 30 minutes for the pain to subside (moderate irritability).

Past interventions:

- Physiotherapy 2.5 years ago with no effect

- Therapist only used passive treatment (i.e., stretching, PROM, and modalities like NMES to treat the lower extremity)

- Massage Therapy: Attended weekly for 3 months (2020) with no effect.

- Acupuncture: Attended weekly for 3 months (2020) with no effect.

- Pharmacological Agents: Baclofen (prescribed by a neurologist to treat muscle spasticity) but stopped after a couple of months as it was not helpful and the side effects experienced outweighed the benefits associated with the medication.

Past Medical History[edit | edit source]

- Depression

- Otherwise functionally healthy

Medications[edit | edit source]

- Lexapro (10 mg OD, for 8 weeks) - to treat depression

- Clonazepam (0.5 mg TID) - to treat muscle spasticity

Health Habits[edit | edit source]

- Smoking History: Non-smoker

- Alcohol Consumption: Maximum of 4 alcoholic drinks per week

- Recreational Drug Use: N/A

Family History[edit | edit source]

- Mother: Diabetes and Hypertension

- Father: Colon Cancer

- No family history of PLS or other neurodegenerative diseases

Psychosocial[edit | edit source]

Mr. Parker experiences feelings of depression often, such as hopelessness, frustration, and general sadness. He has developed a strong fear of falling due to his poor balance that has forced him to guide himself using walls, railings, and installed support bars throughout his home. This constant need for support has dampened his courage and motivation to ambulate or exercise. Mr. Parker’s previous highly active lifestyle has made it difficult to adjust to his current, more sedentary lifestyle. He constantly worries about burdening his wife with their household chores, especially because of her lower back pain. The growing conflict between his inability to perform his usual activities and desire to help his wife and family business has made him increasingly irritable and restless.

Social History[edit | edit source]

Mr. Parker lives in a bungalow with his wife and two small dogs. The house has three concrete steps leading up to the front door, and 10 stairs inside to get down to the basement. Has one bedroom on the main floor with a full bathroom, and a half bathroom closer to the living room. Hardwood flooring throughout the hallways, tile floor in the kitchen, and carpet in the bedroom. He enjoys spending time with his two granddaughters, taking them to the park by his house during the summer and skating with them during the winter. He used to work part-time at his family-owned construction company which he enjoyed greatly, but has had to retire early due to the progression of his disease.

Functional History[edit | edit source]

Mr. Parker reports being very active prior to disease onset as he participated in CrossFit, attended the gym 2-3x/week, and ran 3-5km twice a week. He used to drive up until about a year ago (2021) when needed but would walk or bike to his destination whenever possible. He was able to complete all activities of daily living, household chores, and property management (i.e. mowing the lawn and gardening) independently. He denies the use of mobility aids prior to being prescribed a single-point cane by his previous PT in 2019. Prior to his diagnosis, he ambulated freely with no balance issues or worries of falls.

Current Functional Status[edit | edit source]

He is currently able to ambulate for 10-30 minutes independently. He utilizes a single-point cane with a 2-point step-through pattern when feeling fatigued or when he needs a boost of confidence ambulating for longer distances. At home, he currently performs light upper extremity exercises using a resistance band. He is able to perform light household chores such as dusting, folding laundry, and washing dishes, but needs assistance from his wife for heavy chores like vacuuming, lifting anything heavier than 25 lbs., and shopping. He is currently able to perform self-care activities in full with no reports of difficulty. As mentioned above, Mr. Parker has refrained from driving since one year ago due to generalized weakness and fatigue. He is only able to ascend and descend the stairs outside and inside his house if he holds onto both railings or one railing and his cane. He reports feelings of being unbalanced often in a variety of situations like going up or down a set of stairs, intermittently when standing, and walking for long periods of time.

Imaging and Medical Testing[edit | edit source]

EMG: Found sparse fasciculation in bilateral calves. Conducted on April 3, 2022.

Nerve Conduction Studies: No outstanding results were found. Conducted in both May 2021 and April 2022.

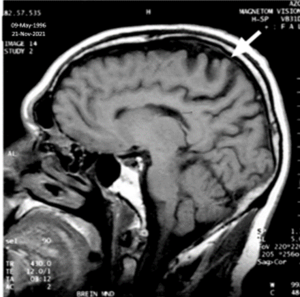

MRI: Sagittal T1 weighted image of the brain showing atrophy of the pre-central area and degeneration of the underlying white matter [10]. Imaged on November 21, 2021.

Precautions/ Contractions[edit | edit source]

Concurrent depression, emotional lability (particularly regarding heightened irritability and uncontrollable sadness), and intermittent difficulty swallowing due to dysphagia.

Objective[edit | edit source]

General Observations[edit | edit source]

| Standing Posture |

|

| Sitting Posture |

|

Speech and Language[edit | edit source]

Mr. Parker’s wife indicates that the hoarseness in his voice became apparent several months ago and was not present before. His language abilities are intact upon examination and mild notes of hoarseness are noted during the assessment.

Tone and Sensation[edit | edit source]

Tone was assessed using the Modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale (MAS). Findings include:

| Muscle Group | Grade |

|

3 |

|

1+ |

Sensation was assessed using the dermatomal pattern for light touch along upper and lower extremities, as well as vibration sense in lower extremities. There was no abnormality in sensation found.

Muscle Strength[edit | edit source]

Global muscle strength for the upper and lower extremities was measured using manual muscle testing (MMT). See tables below.

Upper Extremity MMT:

| Muscle Group | Grade: Left | Grade: Right |

| Shoulder Flexors | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Shoulder Extensors | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Shoulder Abductors | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Shoulder Adductors | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotators | 4-/5 | 5/5 |

| Shoulder External Rotators | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Elbow Flexors | 4+/5 | 5/5 |

| Elbow Extensors | 4/5 | 5/5 |

Lower Extremity MMT:

| Muscle Group | Grade: Left | Grade: Right |

| Hip Flexors | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Hip Extensors | 4-/5 | 4-/5 |

| Hip Abductors | 4+/5 | 4+/5 |

| Hip Adductors | 4+/5 | 4+/5 |

| Hip Internal Rotators | 4+/5 | 4+/5 |

| Hip External Rotators | 4+/5 | 4+/5 |

| Knee Flexors | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Knee Extensors | 4-/5 | 4/5 |

| Ankle Plantar Flexors | 3+/5 | 3+/5 |

| Ankle Dorsiflexors | 4/5 | 4/5 |

Active Range of Motion (AROM)[edit | edit source]

Measured using a goniometer.

Upper Extremity AROM:

Limitations in AROM were noted for the movements in the table below. All other movements were WNL bilaterally.

| Movement | Left | Right |

| Elbow Extension | 10° of flexion | 0° |

Lower Extremity AROM:

Limitations in AROM were noted for the movements in the table below. All other movements were WNL bilaterally.

| Movement | Left | Right |

| Hip Flexion | 90° | 90° |

| Hip Extension | 5° | 5° |

| Knee Flexion | 125° | 125° |

Trunk AROM:

| Thoracic Spine Movement | Findings | Lumbar Spine Movement | Findings |

| Flexion | 35° | Flexion | 45° |

| Extension | 40° | Extension | 20° |

| Side Flexion | R: 25° L: 20° | Side Flexion | R: 20° L: 15° |

| Rotation | R: 35° L: 30° | Rotation | R: 10° L: 5° |

Passive Range of Motion (PROM)[edit | edit source]

PROM was measured using a goniometer. Measurements obtained were recorded as WNL when moved slowly at 3s through joint PROM. All movements in the upper and lower extremity were WNL bilaterally, with the exception of elbow flexors:

- Spastic increase in elbow flexors when moved fast <0.5s through joint PROM of elbow extension.

Balance[edit | edit source]

Balance was assessed using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) at baseline. Score achieved: 46/56.This score indicates the patient is independent, should not require assistance to ambulate safely. However, this score does indicate that Mr. Parker is at an increased risk for falls.

Gait[edit | edit source]

Wide-based stance, slowed gait, driving feet into the ground with each step. Left arm in full extension and absence of arm swing on left side (to avoid onset of spastic episode of elbow flexors).

Ambulates with a single point cane with 2-point step through pattern for longer distances. Does not use it daily.

| Outcome Measure | Score | Interpretation |

| Gait Speed Test (4 meters) | 0.82 meters/second | Indicates that Mr. Parker may independently ambulate in the community safely,, but will need interventions in place to reduce falls risk. |

| Tandem Gait Test | 10 steps | Mr. Parker completed 10 steps of the tandem walk without the use of his cane in an unsteady and uncoordinated manner, having to widen his stance with almost every step. This is indicative of mild balance and gait disturbances. |

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

DIAGNOSIS[edit | edit source]

PROBLEM LIST[edit | edit source]

PATIENT GOALS[edit | edit source]

Short-Term Goals (STG)[edit | edit source]

Body Structure/Function

Activity

Participation

Long-Term Goals (LTG)[edit | edit source]

Body Structure/Function

Activity

Participation

INTERVENTION[edit | edit source]

Management Program[edit | edit source]

PLS treatment strategies are aimed at managing patient-specific symptoms and maintaining available functional abilities. A goal-oriented and functional intervention program has been created for Mr. Parker that considers his disease progression, preferences, and goals. The program highlights activities that will be performed in an outpatient neurological rehabilitation in Toronto and activities that he will be coached to perform at home. Although education, strengthening, and flexibility can be the central aspect of the treatment plan, growing research has shown standing in patients with neurological disorders is beneficial for ROM, spasticity, and psychological well-being (6). In addition, standing has also been shown to promote the maintenance of anti-gravity muscles in the trunk and lower limbs [11]. For this reason, Mr. Parker is instructed to perform many of these exercises in standing as tolerated.

Out-patient Neurorehabilitation Treatment Plan[edit | edit source]

Education[edit | edit source]

The teach-back method was used to confirm patient understanding.

| Topic | Description |

| Fall Prevention Strategies |

|

| Spasticity |

|

| Pain Management |

|

Intervention[edit | edit source]

| Topic | Description | Parameters |

| Balance and Fall Prevention Strategies |

|

F: 2 days/week

I: As tolerated T: 3 sets of 30 seconds reps |

| Behavioral Therapy |

|

Ongoing |

| Virtual Reality System (VRS) |

|

Introduced after 4 weeks in PT

F: 2 days/week T: 10 minutes |

| Rhythmic Cycling |

|

F: 2 days/week

I: Moderate intensity T: 15-20 minutes, or as tolerated T: Aerobic |

Home Exercise Program[edit | edit source]

Stretching[edit | edit source]

| F.I.T.T. | Description | Exercises |

| Frequency | 2-3 days/week; encouraged daily | Upper Extremity:

Lower Extremity:

|

| Intensity | To the point of tightness or slight discomfort; no pain | |

| Time | Hold stretch for 30 seconds, for an accumulation of 60 seconds/day | |

| Type | Static |

Strengthening[edit | edit source]

| F.I.T.T. | Description | Exercises |

| Frequency | 2-3 days/week |

|

| Intensity | 8-12 reps (to muscle fatigue, but not pain)

2-4 sets 70-80% 1RM | |

| Time | 2-3 min rest between sets | |

| Type | Hypertrophy |

Balance Training[edit | edit source]

| F.I.T.T. | Description | Exercises |

| Frequency | 2-3 days/week | Internal Perturbations:

External Perturbations:

|

| Intensity | As tolerated | |

| Time | 10-12 reps | |

| Type | Balance |

Aerobic Training[edit | edit source]

| F.I.T.T. | Description | Exercises |

| Frequency | 5-7 days/week |

|

| Intensity | Light-to-moderate intensity | |

| Time | 10-30 minutes, as tolerated | |

| Type | Aerobic |

OUTCOMES - Reassessment After Four Months[edit | edit source]

REFERALS[edit | edit source]

While conversations were had with Mr. Parker and his wife early on with regards to referrals to other health care professionals, it was only recently decided to further explore other available services - including SLP, psychologist, and PT and OT home services.

- Speech-Language Pathology (SLP): To assess speech impairments and swallowing abilities. Services provided may include the application of speech synthesizers, swallowing therapy, improvement of larynx elevation, and strengthening of tongue and suprahyoid muscles [12][13].

- Psychiatrist: To assess and utilize cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to aid in the management of behavior and cognitive changes experienced by the patient. Provide emotional support to the patient and family.

- Occupational Therapy (OT): To assess and practice day-to-day tasks, suggest home equipment and assistive devices. To assist in the elimination of hazards in the patient’s environment by providing feedback on changes to the layout of the home, installation of bathroom equipment (i.e.., grab bars, bath bench, etc.), and ensure adequate lighting to aid in fall prevention.

- Medical/pharmaceutical:

- To prescribe oral medications and the appropriate dosage for management of spasticity such as baclofen, tizanidine, or valium [14].

- Growing research has shown the benefits of using stem cell in slowing the progression of ALS [15]. Considering the similarities between ALS and PLS, there has been a move to consider stem cell therapy as an alternate therapeutic strategy for PLS [15].

- Surgical intervention: implanting baclofen pump [14]

DISCHARGE PLAN[edit | edit source]

Due to the progressive nature of Mr. Parker’s condition, a discharge plan is not indicated and ongoing assessments are recommended to monitor and manage his symptoms and physical functioning.

Less frequent physiotherapy visits are required as Mr. Parker is managing his symptoms well, is compliant with the treatment protocol, and has developed appropriate self-management strategies.

DISCUSSION[edit | edit source]

PLS is a rare and sporadic upper motor neuron disease that is often mistaken for ALS [16]. In addition to impeding functional activities, muscle weakness, spasticity, and loss in ROM, this condition can negatively impact one’s outlook on life. This comprehensive fictional case study was developed to increase the awareness of PLS and to find and integrate evidence-based practice in the assessment and treatment of this condition.

Mr. Parker is a 56 years old male who was initially diagnosed with ALS 3 years ago. Upon further assessment of his symptoms, he was diagnosed with PLS. Mr. Parker was an active individual; running, CrossFit training, and working out at the gym up until the presentation of his symptoms. His physiotherapy assessment revealed global muscle weakness in the lower extremity, increased tone in left elbow flexors and bilateral hip flexors, painful spastic posturing, and reduced ROM in his left arm. He has also reported to have episodes of swallowing difficulty and issues with balance contributing to increased risk for falls. In addition to his condition, being functionally independent previously to currently needing constant support has greatly impacted Mr. Parker’s behavior and emotions. Mr. Parker often experiences frustration, uncontrollable sadness, and hopelessness.

An intervention program focusing on education, maintaining strength, ROM, reducing spasticity, and improving balance have been geared to improve Mr. Parker’s quality of life and ability to perform functional activities. Additionally, Mr. Parker will be taught fall prevention strategies, and dexterity training, and receive cognitive behavioral therapy. Along with his physiotherapists, a multidisciplinary team including SLP, OT, physician, neurologist, and psychiatrist will be involved in his care to assist him in pain management, mental health, changes in his home environment, and dysphagia related symptoms.

The progressive nature of PLS involves patient concern and the need for specified treatment as in other progressive conditions such as Ankylosing Spondylitis, muscular dystrophy, Alzheimer’s, and more. Additionally, since PLS is a condition of UMN degeneration, the physiotherapy interventions and diagnostic tests used in this particular case could be implemented in other cases involving the UMNs. Due to the progressive nature of this disease, this case outlines the focus on managing the disease and the deficits it presents more than on treating it. This maintenance approach needs to be conveyed to patients effectively through consistent education and positive framing. Additionally, realistic expectations and goals should be discussed and implemented early on in order to make sure they are actually achieved.

The emotional, physical, and social impact of PLS discussed throughout the case shines a light on the multidimensional characteristics of such a disease. Further, in this particular case, patient concerns and goals often pertain to their ability to participate in various activities, both recreational and social. Thus, the treatment focus of the interdisciplinary team for those with PLS or any other condition should be directed towards making the interventions as meaningful as possible to the individual. This case also emphasizes the importance of assessing the patient correctly to obtain the best understanding of their previous capabilities and current deficits. An in-depth initial assessment, as outlined in this case, is therefore crucial in the patient’s prognosis and avoiding mental fatigue when progressing their interventions.

Unfortunately, evidence-based recommendations in terms of diagnostic and outcome measures, and treatment is limited regarding PLS, as indicated throughout this case. Therefore, it is paramount for further research to take place regarding the assessment and treatment of PLS that would be done by physiotherapists and other relevant healthcare professionals. Evolving the current research on PLS will potentially aid in the timeliness of an accurate diagnosis, identification of proper management, and treatment interventions. Additionally, there should be some consideration towards investigating proactive measures that may delay onset of the disease itself. Aspects of future research may also be applicable to other UMN diseases.

SELF STUDY QUESTIONS[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Physiopedia. Primary Lateral Sclerosis. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Primary_Lateral_Sclerosis (last accessed 09/05/22)

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Mayoclinic. Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Diseases and Conditions. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/primary-lateral-sclerosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353968 (last accessed 09/05/22)

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Turner MR, Barohn RJ, Corcia P, Fink JK, Harms MB, Kiernan MC, Ravits J, Silani V, Simmons Z, Statland J, van den Berg LH; Delegates of the 2nd International PLS Conference, Mitsumoto H. Primary lateral sclerosis: consensus diagnostic criteria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;91(4):373-377. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-322541.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Gordon PH, Cheng B, Katz IB, Pinto M, Hays AP, Mitsumoto H, Rowland LP. The natural history of primary lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2006 Mar;66(5):647-53. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200962.94777.71

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Le Forestier N, Maisonobe T, Spelle L, Lesort A, Salachas F, Lacomblez L, Samson Y, Bouche P, Meininger V. Primary lateral sclerosis: further clarification. J Neurol Sci. 2001 Apr ;185(2):95-100. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00469-5.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Zhao, C, Lange, DJ, Wymer, JP. Management of Primary Lateral Sclerosis. Current Treatment Options Neurology. 2020 Aug; 22(31). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-020-00640-6

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Wais, V, Rosenbohm, A, Petri, S, Kollewe, K, Hermann, A, Storch, A, Hanisch, F, Zierz, S, Nagel, G, Kassubek, J, Weydt, P, Brettschneider, J, Weishaupt, JH, Ludolph, AC, and Dorst, J. The concept and diagnostic criteria of primary lateral sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2016 Oct;136: 204– 211. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12713h

- ↑ Faldi Yaputra. Primary Lateral Sclerosis. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcyAMDAPEeI [last accessed 11/05/22]

- ↑ Stitching PLS. Primary lateral sclerosis, English subtitles Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zpt1-QTUbXE [last accessed 11/05/22]

- ↑ Kuipers-Upmeijer J, Jager AEJde, Hew JM, Snoek JW, Weerden TWvan. Primary lateral sclerosis: Clinical, neurophysiological, and magnetic resonance findings. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.2001. Available from: https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/71/5/615 (last accessed 10/05/22)

- ↑ Stevenson VL. Rehabilitation in practice: spasticity management. Clin Rehabil. 2010 Apr; 24(4):293-304. doi: 10.1177/0269215509353254

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Martindale N, Stephenson J, Pownall S. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Plus Rehabilitative Exercise as a Treatment for Dysphagia in Stroke and Non-Stroke Patients in an NHS Setting: Feasibility and Outcomes. Geriatrics. 2019; 4(4):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4040053

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby-Mann G, Crary M. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:287-298 https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S23404

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Statland JM, Barohn RJ, Dimachkie MM, Floeter MK, Mitsumoto H. Primary Lateral Sclerosis. Neurologic clinics. 2015; 33(4), 749–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.007

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Czarzasta J, Habich A, Siwek T, Czaplinski A, Maksymowicz W, Wojtkiewicz J. Stem cells for ALS: an overview of possible therapeutic approaches. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2017 Jan;57:46-55. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2017.01.003

- ↑ Turner MR, Talbot K. Primary lateral sclerosis: diagnosis and management Practical Neurology 2020;20:262-269. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S23404