Physiotherapy management strategies in people with schizophrenia

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Amber McNeill, Amy Westley, Emma Moisey, Fiona Bartholomew, Sally Phimister, Rucha Gadgil, Kim Jackson, Jane Hislop, 127.0.0.1, Admin, WikiSysop, Claire Knott and Amanda Ager

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Aims and Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

Aims:

1. To provide final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified physiotherapy graduates with an online learning resources which will develop their knowledge and understanding of schizophrenia and its impact on the individual.

2. To enable final year students and newly qualified physiotherapy graduates to develop their knowledge and awareness of physiotherapy management strategies for people/adults with schizophrenia.

Learning outcomes:

By the end of this online learning resource you should be able to:

1. Identify and evaluate the biopsychosocial impact of schizophrenia on the individual.

2. Explain the effects of the common medications used in the management of schizophrenia and how these effects can impact physiotherapy management.

3. Critically appraise the evidence underpinning some of the key physiotherapy management approaches for schizophrenia and reflect on how the could be used in practice.

4. Select evidence informed communication strategies to be able to interact effectively with individuals with schizophrenia.

What is This Wiki and Who is it For?[edit | edit source]

This wiki has been produced by a group of 4th year students from Queen Margaret University to promote a clear understanding of the role a Physiotherapist plays when assessing and treating patients with mental health disorders. The wiki intends to further educate physiotherapy students and new graduates and should take approximately 10 hours to complete. This is for individual study and can be used as continual professional development (CPD)

This wiki will explore what mental health is and the stigma associated with it. The focus will be on the management of schizophrenic patients however the information could be transferable to other mental health disorders.

The resource will cover a range of topics which will aid your learning and influence how you manage people with schizophrenia. These topics include: pharmacological management; common communication strategies which could be used; the importance of health promotion in physiotherapy as well as some physical therapy interventions. This resource is informed by current guidelines, policies and literature.

[edit | edit source]

Within this wiki you will find a number of hyper-links. Some of these will allow you to navigate ‘within’ the wiki and others will navigate you to external resources that could further your learning.

Throughout this wiki there are a number of interactive tasks. Faber (2013) explains that every individual has different learning styles including visual, kinesthetic or auditory. The tasks that have been created for you to complete have been designed to achieve the higher levels of learning which are demonstrated at the top of the blooms taxonomy hierarchy (see figure below).

For the first task you are asked to take 15 minutes just now to write down a summary of everything you know about the subject. This can include information learnt from other resources, from past experiences or/and from personal experiences. Also write down what you think you might like to know more about. Be clear about what it is you want to gain from this resource. You will be asked to refer back to this towards the end of the wiki.

Mental Health[edit | edit source]

What is Mental Health?

[edit | edit source]

Definition:

“Being mentally healthy means you can; make the most of your potential, cope with life, and play a full part amoungst society, family and the workplace.”

“Mental health can also be called emotional health” (Mental Health foundation 2015).

Please take 5 minutes to watch this video. It will give you an illustrated understanding of what good and bad mental health is and the impact it has on everyday life.

Mental health can encompass cognitive and/or emotional well-being. As you will have learnt from the video mental health affects the way we behave, think and feel. Good or bad mental health will impact an individuals’ ability to lead an enjoyable life, maintain physical health and good relationships. The World Health Organisation (WHO) (2003) reports that to have mental health is not merely being free from a mental disorder but recognising one’s own abilities, being able to cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and maintain participation in the community.

Stressful life events such as work stress, relationship break downs and bereavements can have negative impact on a person’s mental wellbeing. In turn these may affect overall life satisfaction, self-esteem and life purpose.

Mental illness is a diagnosable condition (NHS INFROM 2015). It is reported that 1 in 4 people will experience some form of mental health illness throughout their life time. With such a high global prevalence, everyone at some point will know someone with a mental health illness be it a family member, friend or colleague (NHS 2015).

Stigma[edit | edit source]

9 out of 10 people experience discrimination because of the stigma associated with having a mental health condition (Mind 2015).

Although prevalence of mental health disorders is high there is still discrimination and stigma involved with this population. These view points can come from society, within health care, from employers and even family and friends (Mental health 2015?, Bahm and Forchuk 2009).

Society

Stigma is a key barrier for people seeking treatment. With less people receiving care it leads to them having problems in relationships, how they interact in society as well as increasing negative physiological reactions (Gearing et al 2014, Keene et al 2015, Bahm and Forchuk 2009, Idemundia and Matamela 2012).

A systematic review revealed common themes among schizophrenic patients being treated in the community. It appears to be one of the most stigmatised mental health disorders. Within society stereotyping and negative beliefs such as being dangerous, incompetent and strangeness are common. With an increase of Community Mental Health services there should be a focus on reduction of stigmatization. Changing the view point of society will allow patients to interact more freely in their community with out feeling judged. This should be of great importance for the everyone in the future (Mestdagh and Hansen 2014).

Health care

There are less hospital admissions due to misjudgement of real symptoms that may not be related to the mental health disorder. Health professionals may dismiss real medical symptoms as they believe the patients symptoms are psychosomatic rather than physical because of their mental health disorder. This could be seen as stigmatic and deemed unacceptable within a variety of human rights laws (Thornicroft 2011). Compared to the general population it is well documented that there is a lack of access to resources and patients are reporting that they are experiencing discrimination. With more knowledge and experience in this specific population, health care professionals have reported they more positive about their experiences, in turn becoming less stigmatic (Noblett and Henderson 2015, Yildirim et al 2015, Horsfall et al 2010, Mestdagh and Hansen 2014).

Employment

Patients report unsupportiveness within the work place with employers seeming uneducated in the matter. This leads to further worsening of symptoms and social isolation (Mestdagh and Hansen 2014).

With in the UK, Individual placement and support (IPS) is a well known evidence-base support theory to get people with sever mental health illnesses back to work as merely treating patients is not enough to aid full recovery. Using the equality act of 2010, The UK Government has an Access to Work scheme which helps people get back to work after taking a break due to mental health problems. Although the UK is successful in supporting patients back into the community IPS has challenges world wide due to differences in guidelines and education systems. It is well known that employment rates are low in this population. This is due to lack of education and stigma rather than people being unwilling to work (Marwaha et al 2014, Waghorn et al 2014, Waghron et al 2015).

Integration of Mental and Physical Health Care[edit | edit source]

Currently within clinical practice there is a drive to integrate physical and mental health care (The Scottish Government 2012).

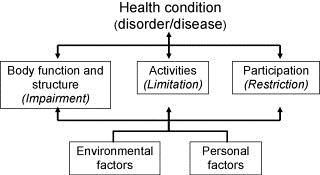

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model (Mittrach et al 2008) as seen below is a widely used tool by physiotherapists which demonstrates how to take a holistic approach when treating a health condition.

It acknowledges the physical, social and mental factors associated with the individual’s condition and shows how they can be linked. Despite physiotherapists dealing with the ‘physical problems’ it is vital to understand how an individual’s physical health can directly impact mental health and vice versa- this will be explored in more detail later in the wiki.

The Mental Health Foundation (2013) have a document titled Crossing Boundaries which you can read to gain a better understanding of integration in health care and how we can assist it.

Why is There a Need for This Physiopedia Page?[edit | edit source]

Literature reviews report 80% of mortality rates in people with serious mental health disorders are strongly linked to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, both of which are related with an increase in substance abuse and morbidity and easily prevented.

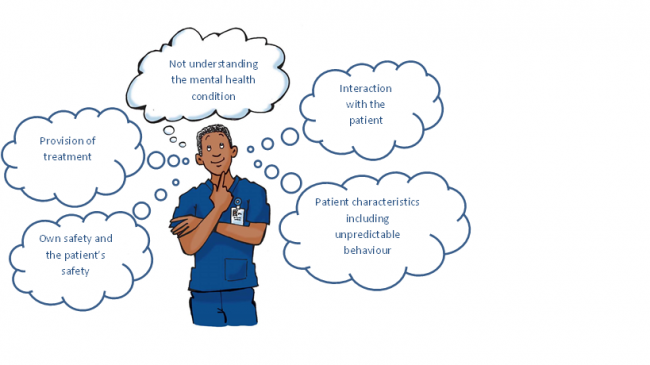

Physiotherapy as a profession working within the mental health specialty is of low popularity however the number of physiotherapists that come into contact on a daily basis with people with mental health issues is high. A national survey of physiotherapy students’ experiences and attitudes towards treating individuals with mental illness was undertaken by Dandridge et al. (2015). 71% of students said they were exposed to less than 4 hours education about mental health and 76% felt they needed more time than this to prepare them. They identified 5 areas in which they were concerned they lacked knowledge as seen below.

If there is going to be more a focus on mental health integration in our practice then physiotherapists need to be more aware about different mental health conditions they may come across and how to approach patients with mental health illnesses.

Common areas in which physiotherapy can help get any individual back to an optimal level of health and function are varied. These include physical health care, pain management, falls prevention and mobility rehabilitation. They have an understanding of how physical dysfunctions can affect daily living tasks; they can implement motivational strategies, weight management programs and are deemed as experts in exercise prescription and health promotion. Therefore including physiotherapy practice within mental health areas has considerable benefits. Due to the nature of assessment physiotherapy can offer patient-centered, evidence-based treatment plans within multi-disciplinary work environments. With a slow growing body of evidence in exercise and cognitive behavioral therapies within mental health, physiotherapists have a growing opportunity and responsibility within this area (Pope 2009).

For the purpose of the wiki information will be geared around physiotherapy management strategies for schizophrenia.

Overview of Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

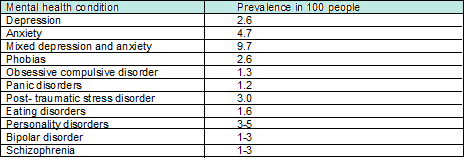

There are many different mental health conditions. The prevalence (the number of people with a given diagnosis at any one time) of some of these is shown below:

Please not that these figures are gathered from people living at home so do not include hospital and prison and figures slightly differ between literature (Mental Health Foundation 2007; Mind 2013).

This learning resource will focus on schizophrenia due to it having a fairly high prevalence and a lack of research compared with other conditions such as depression. Whilst creating this learning resource information was gathered from a lead physiotherapist in mental health who reported that schizophrenia is the most common disorder they come across behind depression/anxiety. Furthermore, a third of people with schizophrenia in the UK report that the care and support they receive worsened in the last two years. This was reported in a new survey by the charity Rethink Mental Illness (2015). These reasons stated have prompted the need for a learning resource.

What is Schizophrenia?[edit | edit source]

Schizophrenia is described as a mental health disorder which causes people to interpret reality abnormally through altered emotions, thinking and behaviour. Its cause is thought to be a mixture of genetic, neurobiological (excessive dopamine levels) and environmental factors. However, its true cause has never been established (Farlex 2015 and WHO 2015).

Facts:

- Schizopohrenia affects more than 21 million people worldwide (WHO 2015)

- Schizophrenia is more prevalent in men and suicide rate amoungst this population is 25-50% (Psychiatric Times 2015).

- 1 in 2 people living with the condition do not receive the care they need (WHO 2015).

- It has a high incidence of relapse making it a difficult condition to live with and treat (Smith et al. 2014).

Please take a few minutes to watch this video about what it is like living with schizophrenia.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

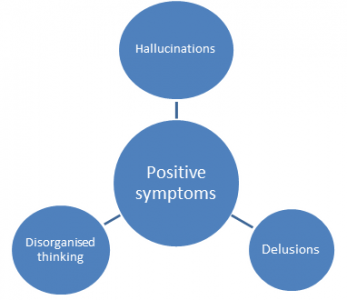

This condition has both ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ symptoms. Positive symptoms are experiences in addition to reality and negative symptoms affect one’s ability to function. The figures below illustrate the symptoms.

The symptoms of schizophrenia affect the person holistically. It is important that these biopsychosocial issues are understood by physiotherapists as they will impact on interaction and management of this patient group in terms of adopting different communication and treatment styles.

Poor Health in Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

It is well documented in the literature that people with schizophrenia have much poorer physical health than the general population and despite having more contact with health services they have a much poorer life expectancy, dying on average 15-20 years earlier. A key factor associated with poor physical health in this population is the high rate of physical inactivity and tendency to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle than the general population (Lindamer et al. 2008, Janney et al. 2013, Stubbs et al. 2014).

In general, physical inactivity is associated with an array of health risks and is said to be one of the leading causes of long term and secondary conditions such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, obesity and different types of cancers (Booth et al.2012 and Lee et al. 2012). It is important to remember that the same health risks apply to people with schizophrenia but due to the nature of their condition and other influencing factors the risk is much greater (Gorczynski and Faulkner 2010).

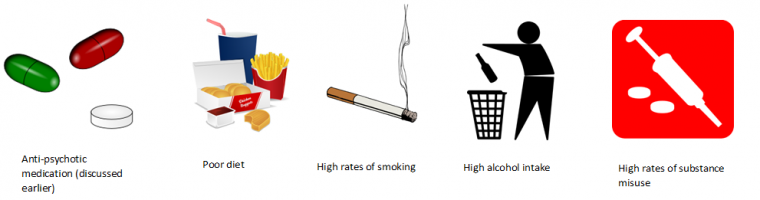

So what other factors could influence the physical health of people with schizophrenia?

(Phelan et al. 2001, McCreadie 2003 and Vancampfort et al. 2012).

In people with schizophrenia, these factors, combined with physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles significantly increase the risk of developing long term conditions compared to the general population.

The facts

People with schizophrenia are:

• 1.5-2 times more likely to be overweight

• Have a 2 fold increased risk of developing coronary heart disease

• Have a 2-fold increased risk of developing diabetes and high blood pressure

• Have an increased risk of developing cancers (which they are 50% less likely to survive)

(Hennekens et al. 2005, NICE 2014, Vancampfort et al.2012).

Medications[edit | edit source]

Introduction to Schizophrenia medication[edit | edit source]

Patients with mental health conditions may need medication to help with any symptoms that they are experiencing to live life normally. In the UK 2.75 million people go to the GP for a mental health condition every year which accounts for one in four GP consultations (Lee and Lyon 2009). Common conditions that require medication are depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia can require 1.5-3% of a health budget spending (Nasrallah et al 2015).

There are five main sub branches of psychotropic medications for managing the effects of mental health conditions.

They are:

- Antipsychotics,

- Antidepressants,

- Tranquillisers/sleeping pills,

- Mood stabilisers

- Beta blockers (MIND 2015).

Each patient is different and may react differently to different medications. Mind.org.uk has an extensive A-Z on drugs used in mental health. Physiotherapists need to be able to understand the effects these drugs will have on the patients ability to interact with physical management. During an assessment or treatment session a Physiotherapist also needs to be aware of how all these medications will affect cognition, proprioception and the patients’ body image.

This video shows how some people feel about taking medication for their mental health disorder. Watch this and consider their view point, does this change how you view mental health pateints?

First Line of Treatment[edit | edit source]

Before medication is offered bio-psychosocial interventions must be tried. Medication has an antagonistic effect on dopamine receptors in the mesolimbic system. Dopamine is associated with positive side effects of Schizophrenia (hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder). Antipsychotics don’t get rid of the disorder but make the symptoms more manageable. The drugs are not specific and do also antagonise acetycholine, histamine, noradrenaline and serotonin receptors. This can have positive and negative results, for some the over sedation can be difficult and for others it can help with sleep disorders (histamine)

| First Generation Drugs (FGA) | Haloperidol, Chlorpromazine Hydrochloride |

| Second Generation Drugs (SGA) | Olanzipine, Quetapine, Risperidone. |

| Thirds generation Drugs (TGA) | Aripiprazole (agonist of dopamine receptors) |

Most common FGA side effects are extrapyramidal (involuntary). Some experience akathisia and dystonia which are sometimes misdiagnosed as aggression (Pringle 2013).

Types of Medication[edit | edit source]

Antipsychotics

The basic aims of antipsychotics are to help the patient feel better or happier without feeling drowsy, alleviate hallucinations and delusions, help patients think clearly, help with extreme mood swings (Manic depressive disorder) and severe depression. Most antipsychotics affect neurotransmitter levels such as dopamine in the brain. Overproduction of dopamine has been linked to hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder (Royal Collage of Psychiatrist 2015). Patients taking antipsychotics will need extra physical prompting when undertaking exercises. Problems with proprioception will need to be addressed with verbal queues and physical prompts.

Antidepressants

Antidepressents help patients alleviate depression and its symptoms. Even though it is not fully understood it is known that two chemicals involved in depression are Serotonin and Noradrenaline. Antidepressants are used in moderate to severe depression, anxiety and panic attacks, Obsessive complusive disorder (OCD), Chronic pain, eating disorders and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Common antidepressants are: amitriptyline, clomipramine, citalopram, fluoxetine, phenelzine and venlafaxine (RCPSYCH 2015).

Tranquilisers/ sleeping pills

Tranquilisers are used for patients to improve sleep patterns and for anxiety disorders (anxiolytics). They have a sedative effect due to an increase in GABA (gamma amino butyric acid) a neurotransmitter. This causes areas of the brain responsible for rational thought, memory, emotions and breathing to slow down. These medications shouldn’t be used long term as patients can become addicted, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) may be more effective for long term management (MIND 2015). Common tranquilisers are benzodiazepines: nitrazepam, flurazepam, loprazolam, lormetazepam and temazepam. Diazepam is commonly used to treat anxiety and insomnia (BNF 2014). When treating patients who are taking tranquillisers, clear and concise instructions should be given as concentration levels may be low. Finding out patient preferences to time of day for treatment is also important as some may find exercises in the morning more difficult compared to the evening or vice versa.

Mood stabilisers

Mood stabilisers allow patients who experience very high and low moods to experience a more balanced life. They are used for patients as a long term treatment option with conditions such as manic depressive disorder. Drugs such as lithium, valproate and carbamazepine are examples of mood stabilisers. The side effects of these drugs can make patients very thirsty. Some patients report that the drugs limit their creativity and flatten their personality. This might combat the mood swings but changes their self perspective and this can be very difficult for patients to deal with (MIND 2015). Lithium is a very effective mood stabiliser and is prescribed as a prophylactic as it has unique anti-suicidal properties. Patients need to have good kidney function as it is an element that cannot be metabolised by the body. Patients also experience weight gain which can effect their self esteem and body image (Bschor 2014). Unfortunately lithium can be toxic in the long term and cause liver failure from fatty liver disease (LIVESTRONG 2015).

Beta blockers

Beta Blockers are beta-adrenoreceptor blocking agents used for decreasing heart rate by blocking adrenaline receptors (NHS 2015). In mental health they are used for patients with anxiety. They can control rapid heartbeat, shaking, trembling, blushing and sweating. Propranalol is an example of a beta blocker commonly used for anxiety (anxieties.com 2015). Some users may feel light headed so therapies that involve moving from lying to sitting/standing will need to be carefully administered for patients using beta blockers.

Pause here and jot down any medications you have come across on placements or in your studies. Are they similar to any here? Why do you think understanding the different medication groups is important?

Common Side Effects and Physiological Effects[edit | edit source]

Patients with Schizophrenia are more susceptible to the side effects of medication. Common reported side effects of psychotropic medications are: weight gain, impotence, insomnia, chronic sedation and lack of ability to concentrate in activities of daily living. This has lead to 90% of patients not adhering to medication strategies. Patients can use self reported questionnaires, such as the Glasgow antipsychotic side effect scale, to let health professionals know how the medication is affecting their daily life. These questionnaires can improve effective communication between the patient and their health care provider (Ashoorian et al 2014).

Poor physical health and low socio-economic position are associated with poor mental health. Physical activity has been linked to a reduced use of psychotropic medications in middle aged men and women (Lahti et al 2013). Personally tailored exercise regimes are important because all patients will have different side effects from medication (Richardson et al 2005). Some patients with schizophrenia find it difficult to recognise their bodies and some have proprioception issues. It can sometimes be related to the medication but as schizophrenia is a neurological disorder patients have a physiological reason for proprioception issues (Everett et al 1995)

For patients with schizophrenia cognitive impairment can make functional rehabilitation more difficult as this type of impairment is not affected by antipsychotics. Patients find having meaningful relationships, keeping employment and living independently difficult due to their impaired cognition. A study by Michealopalou et al (2013) conducted a systematic review of studies that have trialed Medication and cognitive remediation. It is believed that the cortical neural circuits required for cognition are impaired. Minocycline, modafinil and galantamine have shown positive outcomes on cognition. It in not clear though if the effects of the drugs are maintained after the course has been completed. This means that there might not be a translation to functional ability. Physical Activity was having an effect on the plasticity of neural tissue in some studies. The activity had an effect on seratonin release. This paper recommends CBT and medication as the best way to manage cognitive impairment.

The implications for Physiotherapy would be understanding each patients level of impairment and understanding that they might struggle with directions or remembering exercise sets as well as understanding what they are using to manage their symptoms to aid functional rehab.

Medication Challenges in Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Many patients don't adhere to their medication programmes which can make symptoms worse leading to functional problems.

Participants in a study by Boardman et al (2014) found they were missing 7.8 doses on average at their base line. Taking part in a peer support group to encourage each other to take their medication patients found by week 8 of the study their adherence had improved significantly to only 1.3 missed doses. This proved that peer support improved adherence greatly.

A Physiotherapists role may not be physical when it comes to medication adherence. Using verbal encouragement could improve medication compliance allowing patients to get the most out of physiotherapy sessions. Some may argue it is not a physiotherapists place to tell patients to take medication, however, as health professionals we have a duty of care to our patients.

A lot of this wiki focuses on adult patients with mental health conditions. As Band 5 it may be possible to be involved in paedrtic mental health services. Using NICE Guidelines 2013 for Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management, it can be understood that 6 weeks of quetiapine can improve symptoms of psychosis from first onset which is similar to the adult population. Patients can be limited by weight gain, lipid disturbance and raised blood pressure. Long term use of olanzipine in children aged 12-18 years old has the same metabolic effect in adults. Weight gain did seem to be more of a problem for children. there is also an increased risk of getting Diabetes (DMT1). There is a high prevalence of smokers in 12-18 year olds who are taking antipsychotics compared to the general population. From this the challenges may be very similar to the adult population. Health promotion and exercise regiemes may be the best treatment for this patient group. As weight gain is an issue which could lead to body image issues exercise for cardiovasuclar benefit as well as weight management may be recommended.

Physiotherapy Management Approaches in Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

This section of the wiki will focus on the role of the physiotherapist in health promotion and encouraging physical activity. It will look at some of the strategies that physiotherapists can use and the barriers they may face.

The Role of the Physiotherapist in Health Promotion[edit | edit source]

We already know that this population have poor physical health. Many of the factors that contribute to the poor physical health are said to be ‘modifiable’ i.e. they can be changed and physiotherapists are key to this process.

Health promotion is “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health” (WHO 2016). Kaur et al. (2013) identify that making simple lifestyle modifications can result in improved health and quality of life in individuals with mental illness. One of the main ways that physiotherapists promote health is by encouraging physical activity. The CSP (2008, p.5) believes that physiotherapists have a key role in “enabling physical activity for health promotion, disease prevention and relapse”.

A recent qualitative study looking at physiotherapists’ perspectives of their role in managing patients with schizophrenia also identified promoting physical activity as one of the most important ways to promote health in people with schizophrenia (Stubbs et al. 2014).

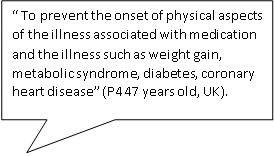

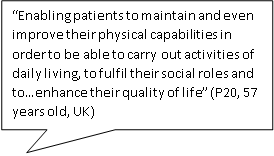

Table X: View of physiotherapists from Stubbs et al. (2014) relating to health promotion and physical activity

Encouraging people to be more active has the potential to improve the physical health of people with schizophrenia whilst also having a positive influence on their mental health and social functioning (Kaur et al. 2013).

As well as encouraging physical activity, other factors involved in health promotion include promoting healthy diet, weight management programmes, smoking cessation and reducing alcohol intake.

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” (WHO 2015).

Benefits of Physical Activity - The Evidence[edit | edit source]

Before exploring the evidence surrounding physical activity, we feel that it is important to understand what this term means. The words physical activity and exercise are often used synonymously however they do in fact have slightly different meanings.

The World Health Organisation (WHO 2015) defines physical activity as, “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.” Exercise on the other hand is a specific type/form of physical activity and is said to be; planned, structured and purposeful with an aim to improve physical fitness and experience the associated health benefits (Robb 2009).Table 1. gives a few examples of general physical activity and more specific forms of exercise. It is clear to see that ‘exercise’ will require higher rates of energy expenditure than some of the more general forms of physical activity (e.g. those associated with daily living), and as such may have greater health benefits.

| General Physical Activity | Exercise |

|

|

Despite this, any form of physical activity that is performed regularly, and sustainable, is paramount in people with schizophrenia due to the sedentary behaviours they adopt.

It is encouraging to see that quantitative studies have found that physical activity can result in improvements in both physical and mental health in people with schizophrenia. Research of a qualitative nature has also been conducted which allows us to hear how physical activity can benefit people with schizophrenia, from the individuals themselves, rather than through numbers and statistics. Soundy et al. (2014) recently used a meta-ethnographic approach to synthesise the existing research that has reported the experiences of physical activity of patients and the health care professionals who work with them. The review included 11 articles: 8 considering the experiences of patients and 3 considering experiences of HCP’s. The benefits of physical activity were grouped into three ‘sub-themes’: Bio-psychosocial benefits, the broader psychosocial value and group factors that influence PA.

Bio-psychosocial benefits

• Psychological benefits during and after physical activity sessions including a reduction in hearing voices and hallucinations.

• Improved general symptom relief

• Improved sleeping patterns

• Through interaction with others participants had improved feelings towards themselves but also felt they had improved attitudes towards physical activity

The broader psychosocial value

A lot of the quantitative research looks directly at physical health improvements and psychological improvements. Many of the studies included in this review concluded that positive outcomes went beyond direct psychological changes.

• Participants noticed they were more willing to initiate further changes in their life e.g. dietary changes, reduction in alcohol and this made them feel more independent

• Through physical activity, confidence and self-esteem improved allowing for increased participation/socialisation within the community

• Increased energy and stamina to be able to achieve more throughout their day

• The structure of exercise/ physical activity gave people a sense of purpose

• Participants and HCP’s recognised the importance of social support (something which will be covered in a later section of this wiki).

<u</u>

Group factors influencing physical activity

It is important to remember that each person is different. Some participants do prefer to exercise on their own however the benefits of being part of a group were well documented throughout this review:

•Being part of a group allowed for participants to motivate each other

•It provided positive relationships and connection to others

•PA within a group allowed for cohesion between individuals and was reported to be an important facilitator of positive change

•Being part of a group gave people a sense of belonging and made participation easier as well as reducing anxiety

•Positive staff relationships was reported to act as an incentive to engaging in physical activity

This review does have some limitations; the number of studies was relatively small (n=11) and the context in which these had been undertaken was quite specific meaning the generalisability may be limited. This review also included English written articles only meaning some valuable information may have been missed. Despite these limitations, the qualitative information gathered is invaluable. This review confirms the psychological and general physical health benefits associated with physical activity (as reported in a number of quantitative studies), however it also highlighted that some benefits cannot be measured and can only be appreciated and identified through research of this nature.

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier, people with schizophrenia spend large periods of their time being sedentary, with the majority failing to meet the physical activity recommendations of 30 minutes per day (REF). As final year physiotherapy students or newly qualified physiotherapists it is important to be aware of any barriers that you may face when trying to promote healthy lifestyles and physical activity in people with schizophrenia.

Before moving onto the next section, take 10-15 minutes and jot down any potential barriers that you can think of. Hint: Consider some of the information that you have already read and think about all of the different factors that could be influencing the patient.

Recent research by Soundy et al. (2014) and Rastad et al. (2014) has looked to establish and explore the factors that could be impacting an individual with schizophrenia’s participation and engagement in physical activity. These two studies take a qualitative approach with one looking at the opinions/experiences of specialist mental health physiotherapists (Soundy et al. 2014) and the other looking at the views and experiences of individuals living with schizophrenia (Rastad et al. 2014)

Analysis of the responses that were collected throughout the two studies generated very similar results. The barriers to physical activity fell, largely, into 3 categories: Physical, psychosocial and environmental.

Physical Barriers

| PATIENT'S PERSPECTIVES(Rastad et al. 2014) | PHYSIOTHERAPIST PERSPECTIVES (Soundy et al. 2014) |

|

Symptoms of Illness and Disease

|

45% - Lack of motivation |

| 27% - Side effects of medication | |

| 21% - Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia | |

| 19% - Fluctuations in mental and physical health |

It is interesting to see that perspectives of those living with schizophrenia are very similar to those providing care to people with schizophrenia. It would appear that the symptoms of schizophrenia, including both positive (hearing voices) and negative (lack of motivation), play a significant part in stopping individuals engaging in physical activity. Along with this, side effects of medication were identified as a major barrier by 27% of the physiotherapists as well as by the patients themselves (e.g.weight gain and increased appetite).

Psychosocial Barriers

Psychosocial barriers have psychological components and social components. The participants living with schizophrenia had pre-conceived misconceptions regarding physical activity and believed that they had to work at their maximum otherwise it was completely pointless and there was no benefit (Rastad et al. 2014). This was also the opinion of 11% of the physiotherapists who felt a lack of understanding of the benefits of physical activity was a major barrier. Lack of confidence, fear of failure and difficulties interpreting new information and feelings from the body, e.g. increased heart rate as a result of exercise, were other psychosocial barriers identified by individuals living with schizophrenia. Participants admitted that they were afraid to attempt physical activity in case they could not manage or achieve the results they hoped for. One participant said: “If I go on with it without any results, then I’m only going to make myself unhappy because I’m not succeeding…” Similarly low self-esteem and low confidence were identified as barriers by 11% of the physiotherapists in the study.

Personal/environmental Barriers

The finally category of barriers addresses personal factors and environmental factors. It was reported by a number of participants that they found getting to the exercise sessions or gyms difficult due to transport difficulty arranging or being able to afford transport (Rastad et al. 2014). Linked into this, a number reported having financial difficulties as a result of gambling and as such were unable to afford a gym membership. 10% of the physiotherapists who responded also agreed with this and recognised financial problems as another barrier to engaging in physical activity.

Hopefully this section of the wiki has given you an insight into personal views and experiences of people living with schizophrenia but also the physiotherapists who treat them. There are limitations of these studies: The study by Rastad et al. (2014) was conducted in an outpatient setting with a relatively small number of participants (20) recruited from 3 cities in Sweden. As it was conducted in an outpatient setting only, the results are unlikely to be representative of individuals in in-patient settings. Also, the availability of medical and psychological treatments for patients with schizophrenia varies among countries and as such, the participant’s experiences will not be the same worldwide. The study by Soundy et al. (2014) also had limitations. The analysis assumed that patients were compliant with their medications – non adherence to medication would significantly impact the main barriers that were identified. Also a physiotherapist’s personal habits in regard to PA could influence his/her enthusiasm/effort to promote PA to patients and could have influenced their responses in the survey.

Despite the limitations, a number of clear themes have been identified. Although the results may not be truly generalizable, the barriers identified are vital to consider when trying to promote and develop physical activity programmes or interventions with patients.

Communication strategies[edit | edit source]

Most physiotherapists will, at some point in their career encounter individuals who suffer from a mental health condition (Priestley 2011) [1]. It may be that the physiotherapist will be treating another condition, but in order to treat the individual holistically, it is important to understand how this condition may impact the delivery of treatment and require a modified approach.

A survey conducted by Dandridge et al. (2014)[2] on the views of physiotherapy students towards treating individuals with mental illness, found that one of the key issues was regarding communication. Students raised concerns about how to approach someone with mental illness, discussing a lack of knowledge of how to communicate effectively or adjust their approach to individual needs. The following section will therefore discuss the topic of communication in the context of schizophrenia, including how this condition may impact effective communication and some strategies to help overcome common these barriers.

Barriers to communication[edit | edit source]

Impact of negative symptoms[edit | edit source]

In schizophrenia, while the positive symptoms (hallucinations and delusions) are widely recognised as the hallmarks of the condition, it is the negative symptoms which are harder to treat and are more indicative of the long-term ability of the individual to function in society (Lang et al. 2013)[3]. These negative symptoms include poverty of thought and speech, apathy, anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), lack of motivation and decreased engagement in social interactions (Weinberger and Harrison 2011)[4]. These symptoms have a significant impact on how an individual experiences life. They usually exist prior to the emergence of positive symptoms and will often endure long after the psychotic symptoms have disappeared (Staring et al. 2013)[5]. Negative symptoms also have implications for physiotherapy treatment as they will affect the client-physiotherapist interactions as well as the ability of the individual to participate actively with their treatment plan.

Deficits in social cognition[edit | edit source]

It has been also identified that individuals may experience deficits in social cognition which can impact their ability to interact socially with others. This can include difficulties with; interpreting facial expressions or tone of voice, recognising the emotions or intentions of others, understanding their own feelings and emotions (Koelkebeck and Wilhelm 2014)[6]. Furthermore, a study by Lavelle et al. (2012)[7] on non-verbal communication found that poor social cognition and increased negative symptoms had an adverse impact on social interactions leading participants to perceive poorer rapport when having conversations with individuals suffering from schizophrenia. Interestingly, a higher level of rapport was reported with individuals exhibiting mild positive symptoms, possibly due to these symptoms manifesting as more engagement with the social interaction. As establishing a therapeutic relationship is essential in patient-therapist interactions (Hewitt and Coffey 2005)[8], it is important that these deficits in social cognition are understood and that clinicians engage in strategies to help establish rapport and ensure effective communication is achieved.

Communication skills[edit | edit source]

Approaches to enhance communication: from Pounds 2010[9][edit | edit source]

A qualitative and descriptive pilot study was carried out to investigate the interaction of an experienced mental health nurse specialist with 3 of her schizophrenic clients. The aim was to describe how she altered her verbal and non-verbal communication in order to enhance effective communication and develop a therapeutic relationship.

Some key approaches that emerged included:

• Exaggeration of facial and vocal cues. As mentioned above, individuals may experience deficits in social cognition, including difficulty reading facial expressions or tone of voice. In this study, the nurse exaggerated her facial expressions (for example, showing concern) or her verbal language (for example, greater inflection in her tone of voice, reflecting a clients’ statement back to them). When applied, these subtle changes in behaviour elicited responses from her clients (such as increased eye contact) and improved their engagement with the interaction.

• Open body language. Displaying open body language, such as leaning forward, smiling and nodding can demonstrate to the client that the clinician is willing to engage with them and can encourage an individual to be involved in the interaction.

• Accepting silence/giving time to answer. Some of the negative symptoms (as mentioned above) that an individual with schizophrenia may face are poverty of thought and speech. This means that when asked a question, a person may require longer to gather their thoughts and give an answer. In her interactions with her clients, there were often periods of silence whilst they were considering a question (lasting between 5-15 seconds).

What can we take from this study?:

The main limitation of this pilot study is that it had an extremely small sample size of three participants and only monitored the behaviour of one clinician, and therefore the results may not be representative of this patient population. However, it does begin to describe what may be some useful but subtle changes to the interactional behaviours of the clinician that could encourage communication and help them connect with their clients (Pounds 2010)[9]. These strategies, in combination with adequate time to get to know the individual will facilitate the building of trust and help establish a positive therapeutic relationship (Cameron at al. 2005)[10].

Promoting engagement with treatment[edit | edit source]

A-motivation as a key problem[edit | edit source]

Lack of motivation is one of the main negative symptoms experienced by those with schizophrenia (Wienberger and Harrison 2011)[4] and has been identified as having a significant impact on all aspects of behaviour (Choi and Medalia 2010)[11]. Motivation is essential for engagement in self-care actions and has an important role in the process of change (Pickens 2012)[12]. A qualitative study by Abed (2010)[13] identified lack of motivation to be a major factor that influenced health-related decisions and behaviour. Foussias et al. (2011)[14] conducted a longitudinal study and found that amotivation was responsible for 74% of variance in functional outcomes at baseline and 72% of variance at 6-month follow-up, therefore indicating that motivation has a crucial role in predicting the functional outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia. Addressing motivation is of great importance to promote engagement with change and healthy lifestyle choices within this population (Pickens 2012)[12].

Strategies to enhance motivation[edit | edit source]

Goal setting:

The importance of setting patient centered goals within this population is discussed previously on this physiopedia page. However, it is important to note that working with the client to set personal meaningful goals can help combat amotivation and influence their willingness to be actively involved in their treatment (Dopke and Batscha 2014)[15]. Adams and Drake (2006)[16] discuss how individuals with serious mental illnesses are capable of meaningfully participate in decisions about their healthcare and it is therefore important to involve them in the planning of treatment. The setting of patient centered goals is one way in which a sense of control can be returned to the patient and can increase their self-determination (Dopke and Batscha 2014)[15]. Progression towards personal goals is also considered to be powerful influencing factor in promoting psychological recovery (Clarke et al. 2009)[17].

Social support:

It has been documented that social interactions can have a positive impact on adherence, enjoyment and motivation to change (Vancampfort et al. 2013)[18], however, individuals with schizophrenia often feel isolated by their condition and have a lack of social support (Soundy et al. 2014)[19]. This is due to a number of reasons including paranoia, social skill deficits, social and emotional processing problems, negative symptoms and stigma (Dopke and Batscha 2014)[15]. A survey of mental health physiotherapists conducted by Soundy et al. (2014)[19] investigated the common forms of support they utilised to engage people with schizophrenia in physical activity. Forty physiotherapists provided in depth responses and from this four dimensions of social support were identified: Informational, tangible, esteem and emotional support. Examples of each dimension are as follows:

Informational:

• Education on benefits of exercise and exercise prescription.

• Providing information on exercise classes.

• May be verbal or written, other forms include diagrams/drawings (consider signposting to online resources).

• Consider the patients individual needs and how to best communicate with them.

Tangible:

• Providing periods of activity under supervised conditions – staff-run or community-led groups.

• Understand the transition and prepare clients for integration into new environment.

• Incentives to promote attendance – support with costs (e.g. free/reduced admission to fitness facilities, support with transport costs.

• Develop connections with local sports centres so they can support people with schizophrenia.

Esteem support:

• Positive reinforcement – identifying positive changes.

• Praise for even very small achievements.

• Encouragement for every physical activity opportunity.

• Consider psychological theories and models to help provide esteem support – e.g. motivational interviewing, self-efficacy and self-determination.

Emotional support:

• Spend time with and listen to the person.

• Active listening and counselling.

• Develop positive therapeutic relationship.

While the results from this survey may not be representative or generalisable, a number of key themes were seen to emerge. Many of these suggestions may be useful for physiotherapists to consider in order to better support their clients in their recovery (Soundy et al. 2014)[19].

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a therapeutic technique commonly used in the treatment of mental health conditions and in the UK the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014)[20] recommends this as a standard treatment to be offered all individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The aim of CBT is to change how individuals manage and view themselves, particularly in relation to how they experience their condition, and involves metacognition; the ability to think about one’s own thinking (Dopke and Batscha 2014)[15]. CBT as a specific treatment approach is usually carried out by psychologists or by staff who have undergone specialist training (O’Connor and Lecomte 2011)[21], but many of the principles of CBT may be useful within everyday physiotherapy practice.

CBT can be helpful in schizophrenia by challenging beliefs and reasoning in relation to their condition, and through enabling people to establish connections between their thoughts, actions, feelings and symptoms (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014)[20]. One example of this is in addressing compliance behavior in those who hear voices (responding to or acting on the commands of the voice). Trower et al. (2004)[22] used CBT to challenge beliefs about these hallucinations in a randomized control trial. They reported a decrease in compliance behaviour in addition to reductions in depression and distress scores. Whilst no change was observed in the nature or frequency of the hallucinations, the individuals perceived the voices to have less power over them. CBT used in this way for psychosis has shown strong effect sizes in comparison to no treatment (O’Connor and Lecomte 2011)[21], however the evidence shows little benefit when compared to other available therapies (Jones et al. 2012)[23]. It has been reported in a number of studies that when positive symptoms have been targeted there has also been some improvement in negative symptoms and this has led to recent research into CBT to specifically target negative symptoms (Klingberg et al. 2011[24], Staring et al. 2013[5]).

Principles of CBT that may be useful in practice

Initially, a trustworthy therapeutic relationship must be built between the client and the therapist and there must be no attempt to label the persons beliefs as irrational (O’Connor and Lecomte 2011)[21]. The aim is to help the individual recognize and process maladaptive behaviours and distorted thinking but this should be done collaboratively (McGrane et al. 2014)[25]. It may be helpful for some individuals to adapt a third-person perspective as though discussing someone else’s beliefs, and the therapist can pose questions to facilitate their evaluation of those beliefs (O’Connor and Lecomte 2011)[21]. Working with the therapist, behavioural goals are set and a plan is then developed in order to attain them, considering how personal barriers, dysfunctional thoughts and behaviours may be overcome. Systematic discussions are used to help individuals identify and modify their thoughts and behaviours and the use of carefully structured behaviour assignments can assist the person in bringing about these changes in their life (McGrane et al. 2014)[25].

CBT may be more useful to physiotherapists where an individual already has the desire to or is already trying to change (McGrane et al. 2014)[25].

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing is another technique that may be of use to help combat lack of motivation in individuals with schizophrenia. It can be described as a way of being with people and helping them to navigate change and must take place in the context of a supportive therapeutic relationship (Pickens 2012)[12]. Motivational interviewing takes the form of a collaborative conversation that is goal-orientated and focused on change, with the purpose of strengthening personal motivation by eliciting and exploring the persons own reasons for change in a supportive environment (McGrane et al. 2014)[25]. It does not externally impose change, but supports change based on their own goals, desires and values (Pickens 2012)[12]. Jackman (2012)[26] states that there are five principles: expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, avoid conflict and arguments, work with rather than fight resistance and support self-efficacy. Five key communication skills are used in motivational interviewing: open-ended questions, affirming, reflecting, summarizing and providing information (McGrane et al. 2014)[25]. In this way, the therapist can guide the thoughts of the client by understanding their position and by asking questions to enable them to reach a point where they are intrinsically motivated to change and feel empowered to do so.

A patient centred approach - treatment planning/goal setting[edit | edit source]

A patient centred approach is vital in the management of people with schizophrenia, particularly with regards to treatment planning and goal setting. Autonomy is something that many of us take for granted. In schizophrenia, the combination of positive and negative symptoms as well as side-effects from the medication can result in major changes in a person’s personality and the way they live their life that this independence can often be lost.

The Royal college of Nurses (2015) describes person centred care as care which allows the person to become an equal partner in their care. It encompasses shared decision making and in direct relation to schizophrenia it is about working together to develop treatments and set goals that are meaningful and at a level the person is ready for, willing to and able to achieve (Fogarty and Happell 2005). An article by Stubbs et al. (2014) found that physiotherapists had a role in promoting active lifestyles and designing individually tailored interventions which would enable the patient to stay active in their own environment.

The practice of setting goals is common in mental health rehabilitation and in general case-management (Clarke et al. 2009). The process of goal setting is key to establishing a positive therapeutic relationship and plan (Dopke and Batscha 2014). Working towards achievable and meaningful goals that have been determined collaboratively by both therapist and client can contribute to greater life satisfaction, promote self-management and reduce psychological symptoms. Moreover, attainment of goals improves the emotional and psychological wellbeing of an individual (Clarke et al. 2009).

Clarke et al. (2009) states that the levels of distress due to psychotic symptoms are related to goal progress, with greater symptom distress having a negative impact on the progression of goals. It is likely that this is because whilst symptoms are severe the individuals focus will be on alleviating those distressing symptoms rather than looking towards future goals. This issue highlights the importance of a patient-centered holistic approach where the alleviation of symptoms is targeted whilst also encouraging the attainment of therapeutic goals in order to promote recovery.

Another article by Clarke et al. (2012) discusses the types of goals set by individuals with psychiatric disorders (majority of participants suffered from schizophrenia) depending on the stage of recovery that they were in. This study found that those within early stages of recovery focused more on “avoidance” goals (reducing an undesirable outcome such as hearing voices) whilst those is later stages of recovery showed an increase in setting “approach” goals (moving towards a positive outcome).

Also notable, was that physical health goals were overall reported most frequently. These included adhering to mental health medications, weight loss, increased exercise, improved nutrition and physical fitness. This may be due to these types of goal being practical and clearly defined. It is suggested that when life goals become unachievable, simple daily goals may help keep depression at bay and provide a sense of purpose. There is therefore a higher prevalence of health goals at the early stage of recovery and it is likely that these more concrete initial goals must be at least partially met before the individual feels able to progress to goals associated with relationships, employment and personal development.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Priestley S. Helping when a mind hurts. Frontline 2011; 17(5). www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/helping-when-mind-hurts (accessed 06 January 2016).

- ↑ Dandridge T, Stubbs B, Roskell C, Soundy A. A survey of physiotherapy students’ experiences and attitudes towards treating individuals with mental illness. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2014; 21(7):324-30.

- ↑ Lang FU, Kosters M, Lang S, Becker T, Jager M. PsychopathologicalfckLRlong-term outcome of schizophrenia – a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2013;127(3):173-82.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Weinberger DR, Harrison PJ. Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Staring ABP, Huurne M-AB, van der Gaag M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for negative symptoms (CBT-n) in psychotic disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 2013; 44(3):300-6.

- ↑ Koelkebeck K, Wilhelm C, Cross-cultural aspects of social cognitive abilities in schizophrenia. In: Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G, Brune M, editors. Social Cognition and Metacognition in Schizophrenia. London: Academic Press, 2014. p29-47

- ↑ Lavelle M, Healey PGT, McCabe R. Is Nonverbal Communication Disrupted in Interactions Involving Patients With Schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Bulletin 2012; 39(5):1150-8

- ↑ Hewitt J, Coffey M. Therapeutic working relationships with people with schizophrenia: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005;52(5):561-70

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pounds KG. Client-Nurse Interaction with Individuals with Schizophrenia: A Descriptive Pilot Study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2010; 31(12):770-3.

- ↑ Cameron D, Kapur R, Campbell P. Releasing the therapeutic potential of the psychiatric nurse: a human relations perspective of the nurse-patient relationship. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2005;12:64-74.

- ↑ Choi J, Medalia A. Intrinsic Motivation and Learning in a Schizophrenia Spectrum Sample. Schizophrenia Research 2010;118:12-19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Pickens J. Development of Self-Care Agency through Enhancement of Motivation in People with Schizophrenia. Self-Care, Dependent-Care and Nursing 2012; 19:47-52.

- ↑ Abed H. What factors affect the lifestyle choices of people with schizophrenia? Mental Health Review Journal 2010;15(2):21-27.

- ↑ Foussias G, Mann S, Zakzanis KK, Vanreekum R, Agid O, Remington G. Prediction of longitudinal functional outcomes in schizophrenia: The impact of baseline motivational deficits. Schizophrenia Research 2011;132:24-27.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Dopke CA, Batscha CL. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals With Schizophrenia: A Recovery Approach. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 2014;17:44-71. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Dopke and Batscha 2014" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared Decision-Making and Evidence-Based Practice. Community Mental Health Journal 2006;42:85-105.

- ↑ Clarke SP, Oades LG, Crowe TP, Caputt P, Deane F The role of symptom distress and goal attainment in promoting aspects of psychological recovery for consumers with enduring mental illness. Journal of Mental Health 2009;18(5):389-97.

- ↑ Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Vansteenkiste M, De Herdt A, Scheewe TW, Soundy A, Stubbs B, Probst M. The importance of self-determined motivation towards physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 2013; 210(3):812-8.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Soundy A, Freeman P, Stubbs B, Probst M, Vancampfort D. The value of social support to encourage people with schizophrenia to engage in physical activity: an international insight from specialist mental health physiotherapists. Journal of Mental Health 2014; 23(5):256-60.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG178 (accessed 04 January 2016).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 O’Connor K, Lecomte T. An overview of cognitive behaviour therapy in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In: Ritsner MS, editor. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume III: Therapeutic Approaches, Comorbidity, and Outcomes. Dordrecht : Springer Netherlands, 2011. p245-65.

- ↑ Trower P, Birchwood M, Meaden A, Byrne S, Nelson A, Ross K. Cognitive therapy for command hallucinations: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2004; 184(4):312-20.

- ↑ Jones C, Hacker D, Cormac I, Meaden A, Irving CB. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(4):CD008712

- ↑ Klingberg S, Wolwer W, Engel C, Wittore A, Herrlich J, Meisner C, Buchkremer G, Wiedemann G. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia as primary target of cognitive behavioral therapy: Results of the randomized clinical TONES study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2011;37(2):98-110.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 McGrane N, Cusack T, O’Donoghue G, Stokes E. Motivational strategies for physiotherapists. Physical Therapy Reviews 2012; 19(2):136-142.

- ↑ Jackman K. Motivational interviewing with adolescents: an advanced practice nursing intervention for psychiatric settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Nursing 2012;25:4-8.