Physical Inactivity in Children with Asthma: A Resource for Physiotherapists

Contributors: Amy Murray, Chrisostomos Koutsos-Grantham, David Cowan, Rui Ling Lee, Shuen Wen Lim and Tommy Flanagan.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Welcome to this online Physiopedia resource on Physical inactivity in children with Asthma: A Resource for Physiotherapists. This page has been designed by a group of 4th Year Physiotherapy students from Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh, as part of the Contemporary and Emerging Issues in Physiotherapy module.

Why is there a need for this resource?[edit | edit source]

Currently there are numerous learning resources for adults with asthma and for physiotherapists aimed to treat adult patients. However, there is a lack of paediatric patient focused resource which correlates to the lack of literature in paediatric asthma. This learning resource is therefore targeted for final year physiotherapy students and newly-qualified band 5 physiotherapists to enhance their familiarity and confidence regarding childhood asthma. As referred down in the Physiopedia page later, there is an increas in prevalance in childhood asthma, and the added pressure that has been placed in acute care services has highlighted the importance of better asthma management in children to minimise hospital admissions. Physiotherapists can play a vital role in education, symptom management and participation roles for children of all ages with asthma.

This online resource will take approximately 10 hours to complete and may be used for self-study or continuing professional development (CPD). However, this should be viewed as a rough guide due to the diverse learning styles and preferences people possess. In order to facilitate this, the resource has been split into several sections, which enables the user to undertake the learning and activities as and when required. Users can choose to complete the resource on their own, with fellow work colleagues and managers or as a group with feedback given on the appropriate section. Within the ten hours spent to complete this online resource, all five learning outcomes listed below should be achieved.

This learning resource has been designed to be informative, interactive and engaging for the user, with maximum benefit gained when full cooperation and application is shown. The user will be required to undertake in-depth reading, critical reflective practice, quizzes, watch videos and complete short clinical case studies to enhance and facilitate a deeper learning. As mentioned above, peoples learning styles vary considerably and due to life being multimodal there are seldom instances where one mode is used, or is sufficient, therefore a diverse range of material has been incorporated to address the different learning styles. Prior to beginning this resource it may be beneficial to undertake the VARK learning styles questionnaire in order to correctly identify your preferred learning style.

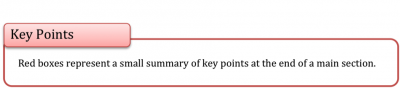

Included in the learning resource will be three different types of action boxes, which all have a different colour and require a different action. They are key points, activity and reflection, and will look as follows:

Aims[edit | edit source]

This interactive online resource targeted at final year physiotherapy students and newly-qualified band 5 physiotherapists aims to:

1) Develop and expand their clinical knowledge on childhood asthma

2) Understand the impacts of physical inactivity via analysis of evidence-based research, theory, policy documents and elements of interactive learning

3) Encourage reflection to highlight physiotherapist attitudes and skills to managing asthma in children

Although this online resource highlights in detail many of the skills and resources needed when managing physical inactivity in children with asthma, further guidance and training may be required for application within clinical practice.

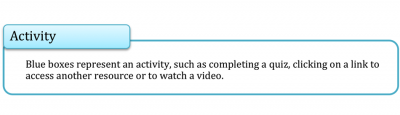

Learning Outcomes

The figure below outlines the five learning outcomes of this online resource and how they will be achieved:

Figure 1. Learning Outcomes

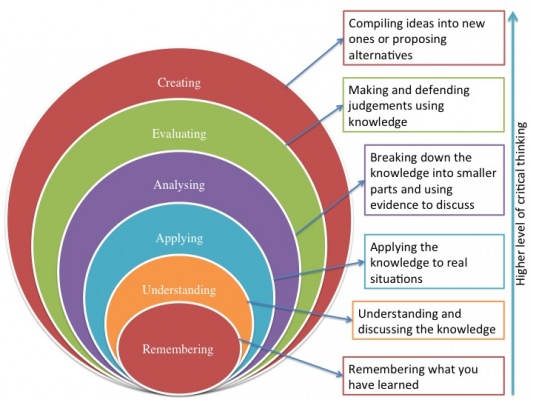

The figure below shows Bloom's Taxonomy as well as a description of the types of critical thinking per level:

Figure 2. Bloom's Taxonomy

[edit | edit source]

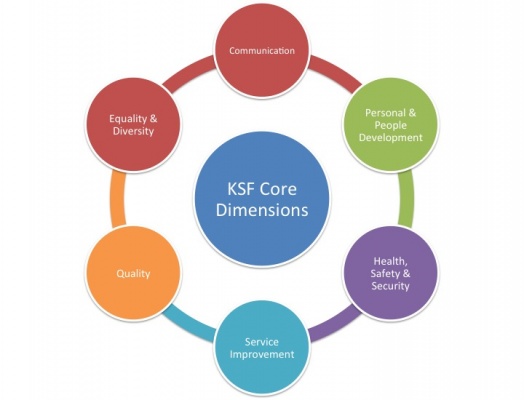

The KSF is a template for basing professional development as the career of the physiotherapist progresses. The KSF ensures that physiotherapists demonstrate specific attributes to enhance efficiency, teamwork, effectiveness and patient satisfaction. Through this online resource, the vast majority of the core dimensions of the KSF will be addressed, equipping learners with the necessary skills required of a band 5 physiotherapist within the NHS.

This online resource will allow you to achieve the following key indicators as shown by the figure below:

1) Communication

- Communicate with a range of people (children, parents, other professionals) in an appropriate manner

- Develops ability to manage barriers to effective communication

2) Personal and people development

- Assesses and identifies what has been helpful in this learning resource via reflective accounts

- Application of knowledge and skills

- Takes responsibility for own personal development and takes an active part in learning opportunities

- Offers information to others when it will help their development or meet their work demands

Figure 3. KSF Core Dimensions

3) Quality

- Works within the limits of own competence and levels of responsibility and accountability in the work team and organisation

- Uses and maintains resources efficiently and effectively and encourages others to do so

4) Equality and diversity

- Recognises people's rights and acts in accordance with legislation, policies and procedures

- Acts in ways that respect diversity and view people as individuals

5) Assessment and treatment planning

- Passes onto the appropriate person constructive views and ideas on improving services for users and the public (online resource learner can promote the concept of the Respiro Initiative in Barcelona to enhance the validity of treatment resources for the public)

How much do you know about Asthma?[edit | edit source]

According to the Global asthma report which was produced in 2014 by the Global Asthma Network (GAN) the most recent revised estimate is said to be approximately 334 million people that suffer from asthma worldwide and therefore the burden of disability is extremely high. This figure is inclusive of both adults and children. GAN is part of a worldwide collaboration that includes over half of the world's countries in order to statistically analyze asthma and its potential difficulties it can cause, in order to provide data required by the World Health Organisation (Global Asthma Network, 2014. Asher and Pearce, 2014).

So how much do you know about Asthma?

Section 1: Background[edit | edit source]

Childhood Asthma[edit | edit source]

According to the the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child, a child is defined as everyone under the age of 18 unless, "under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier" (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 1989).

Activity: Please spend a few minutes watching this Youtube video below on Childhood asthma to familiarise yourself with symptoms, causes and available treatment options.

Definition, Incidence and Prevalence[edit | edit source]

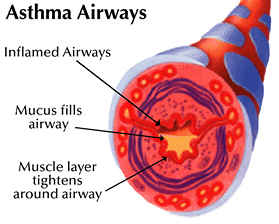

Figure

Asthma is an inflammatory disorder of the airways characterised by “paroxysmal or persistent symptoms such as dyspnea, chest tightness, wheezing, sputum production and cough, associated with variable airflow limitation and a variable degree of hyperresponsiveness of airways to endogenous or exogenous stimuli” (Canadian Thoracic Society 2010).

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB), defined as the transient narrowing of the lower airways following exercise, is common among adolescents (Johansson et al. 2016). In the UK, approximately one in every 11 children are currently receiving treatment for asthma (Asthma UK 2016).

Causes and Classification[edit | edit source]

The table below classifies asthma severity and initiating treatment in children aged between 0-4 years of age:

Figure 4. Classifying Asthma Severity in Children

(Asthma Institue of Michigan, 2017)

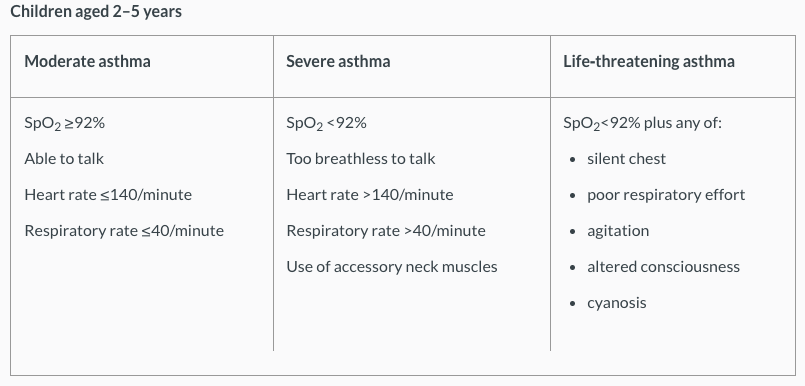

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged between 2-5 years:

(NICE 2013)

Figure

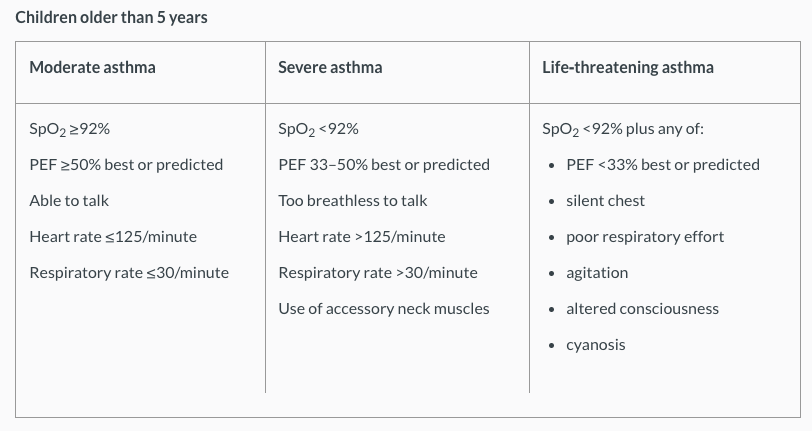

The table below classifies asthma severity for children aged over 5 years:

(NICE 2013)

Figure

Statistics[edit | edit source]

In Scotland, 368,000 people (1 in 14) are currently receiving treatment for asthma. This includes 72,000 children and 296,000 adults (Asthma UK 2016).

Developed by Asthma UK, the SAS visual analytical data can pull together information from locations all over the UK to see the prevalance rates, hospital admissions and percentage of population in the UK that have asthma and actively seek treatment for this.

Please click on the following link to acces the Asthma Uk analytic tool: Asthma UK, SAS Visual Analytical Data

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Definition, Incidence and Prevalance[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines physical activity as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” (WHO 2016).

Children and adolescents aged 5-17 years old are recommended to do at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous-intensity physical activity daily, including muscle and bone strengthening activities at least 3 times a week. (WHO 2016). Even with the knowledge of the benefits of physical activity, participation rate is reported to be insufficient worldwide. Globally, for adolescents that are aged 11-17 years old, it has been found that 81% of them were insufficiently physically active in 2010 (WHO 2016). In Scotland, the Scottish Health Survey in 2015 established that 27% of children aged 2-15 years did not meet the physical activity recommendations, which included school-based activity (Scottish Government 2016).

Children with asthma are generally less active than their healthy peers (Williams et al. 2008). A study by Lang et al. found that children with asthma did an average daily physical activity of 116 minutes compared to that of healthy children of 146 minutes, and children with asthma only did less than 30 minutes of physical activity a day (Lang et al. 2004). Children with moderate-to-severe asthma were also found to have lower physical activity levels than children with mild asthma (Lam et al. 2016).

Sedentary Behaviour[edit | edit source]

Definition, Incidence and Prevalance[edit | edit source]

The Sedentary Behaviour Research Network (SBRN) defines sedentary behaviour as “any waking activity with an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents and a sitting or reclining posture” (SBRN 2016). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children and adolescents to reduce their sedentary behaviour to less than 2 hours per day (American College of Sports Medicine 2014).

Statistics of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour[edit | edit source]

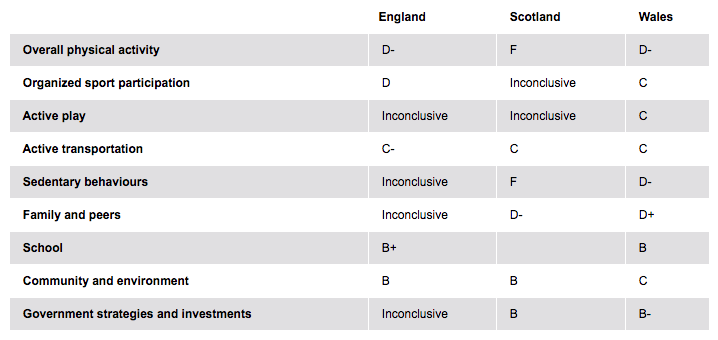

The table below compares physical activity in children between England, Scotland and Wales:

Figure 5. Children's activity across UK

Image taken from www.activehealthykids.org/

Relationship Between Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Obesity in Children with Asthma [edit | edit source]

Physical activity is essential for the normal growth and development of children and adolescents (Hills et al. 2007; Hills et al. 2010; Hills et al. 2011). 60 minutes of physical activity a day has been shown to improve a child’s cardiovascular and bone health, improve their self-confidence and allow development of new social and motor skills (Department of Health 2011; Longmuir et al. 2014). It can reduce sedentary behaviour (Pearson et al. 2014), and is crucial in the prevention of becoming overweight and obese (Strong et al. 2005; Hills et al. 2011), and can contribute to present and future health and wellness by imprinting healthy behaviour habits, reducing risk of future chronic disease (Longmuir et al. 2014).

There is evidence to show that physical activity can improve the asthmatic child’s aerobic and anaerobic fitness (Strong et al. 2005). Physical activity engagement can also reduce school absenteeism, doctor consultations, reduce medication (Welsh et al. 2005), and improve the child’s ability to cope with asthma (van Veldhoven et al. 2001).

There is evidence to show that physical activity can improve the asthmatic child’s aerobic and anaerobic fitness (Strong et al. 2005). Physical activity engagement can also reduce school absenteeism, doctor consultations, reduce medication (Welsh et al. 2005), and improve the child’s ability to cope with asthma (van Veldhoven et al. 2001).

Impact of Asthma on Physical Activity Using the ICF Model

[edit | edit source]

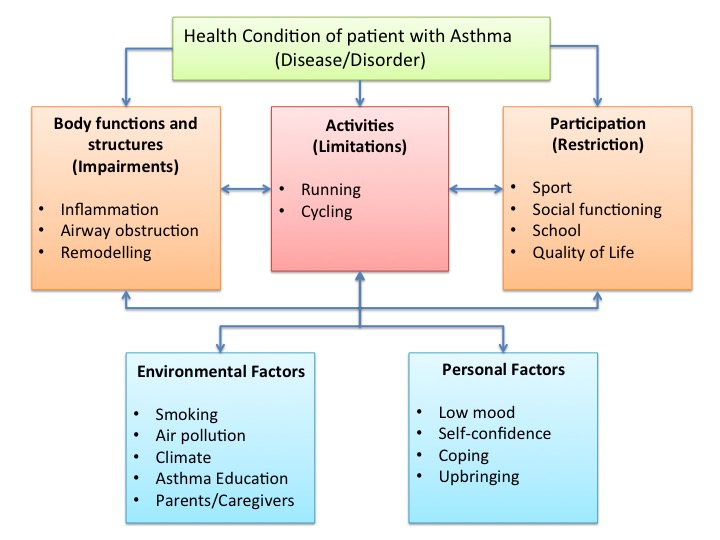

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model is a classification of health and health-related domains and describes how people live with their health condition (WHO 2002). According to the ICF, asthma can influence participation of the child in areas such as sport, school activities, social impact and quality of life (van Gent et al. 2008). Personal and environmental factors such as their parents and asthma education can also play a role in how children with asthma function.

The image below shows the ICF model adapted to children with asthma:

Figure 6. ICF Model of a child with asthma

Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

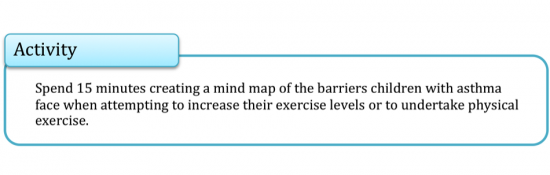

Activity: Perceived barriers to physical activity

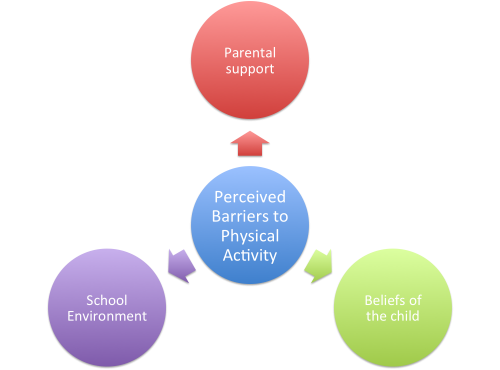

There are 3 main perceived barriers shown in the image to the right. that are involved with the inability to undertake physical activity. These are: Parental support, Beliefs of the child and School environment.

Parental Support

Parental activity-related support has the ability to influence a child’s physical activity levels (Gustafson and Rhodes 2006). A study done in 2004 showed that about one in five parents agree that exercise is harmful for children with asthma, and one in four parents are afraid that exercise would cause their child to fall sick (Lang et al. 2004). Dantas et al established that 37% of mothers imposed restrictions to their children’s physical activity due to negative opinions about asthmatics doing physical activity, perception of children’s dyspnea after running on a treadmill, mother’s anxiety level and children’s asthma severity (Dantas et al. 2014).

Figure 7. Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity

Beliefs of the child[edit | edit source]

Many children with asthma believe that limitations on their activity are an inevitable part of having asthma (Callery et al. 2003). Williams et al. (2008), also suggested that the “desire to meet socially defined forms of normality or "ordinariness", thereby maintaining membership of a valued social group and avoiding stigma or social exclusion” appears to be an important factor affecting participation of physical activity in children with asthma. This may result in low levels of self-efficacy, especially when physical activity engagement is valued amongst their peers.

School environment[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown that a major problem for teachers were differentiating normal consequence of exertion from physical activity to breathlessness due to asthma (Williams et al. 2010). Children may more likely be asked to sit out of physical activity in school so as to reduce the risk of an asthma exacerbation, thereby encouraging children with asthma to not participate in physical activity. Hence, it is important for school teachers to learn to recognise the right signs and symptoms so as to better manage the child’s condition and not send the wrong message to the child with regards to their activity participation.

=== Reflection: Learning Outcome 1 ===

Section 2: Current Policies to Asthma Management[edit | edit source]

Asthma UK[edit | edit source]

Asthma UK is organisation whose goals are to raise awareness of asthma and to support children suffering with asthma. It’s ultimate objective is raise funding for asthma research to potentially find a cure for asthma and new innovations in the treatment of asthma.

Asthma UK advocates the benefits of exercise in children with asthma and recommend they spend at least one hour a day doing some kind of physical activity. They feel as long as the child is managing their asthma well and keeing a good routine with taken their medication exercise will benefit them and improve their confidence about their asthma.

While asthma UK have clear guidelines on what to do in case of an asthma attack and how to handle it, they offer no clear guidance on the intensity or timing of exercise in children with asthma . This is an area of research which would greatly benefit physiotherapists in dealing with pediatric patients with asthma as will will allow use to design an exercise regime and treatment which is backed up by scientific evidence and is shown to be safe. This is an area in which the foundation could provide future research in especially as obesity in children becomes an increasing problem in Britain (Dehghan et al. 2005).

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) [edit | edit source]

While the SIGN guidelines provide similar information on what to do in case of an asthma attack, there is little focus on addressing the efficacy and effectiveness of physical exercise in children with asthma. There is a larger emphasis placed on the medical aspect of asthma management and allergen avoidance. In the SIGN guidelines (2016) for management of asthma, there is only a short mention of improving dietary intake and incorporating exercise based interventions, however this is in relation to weight loss in children and not as a health management strategy in unison with medical management regardless of the child's weight factors.

This guideline in particular is focused almost entirely on the medical approach to managing symptoms. More specifically, in the section of the guideline concerning what a parent can do to help manage their child’s asthma, only the following three instructions are mentioned:

- Making sure the child takes their asthma medication when they should

- Avoiding exposure of the child to cigarette smoke

- Encouraging the child to lose weight if necessary (SIGN 2014)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

[edit | edit source]

NICE (2016a) state that there is no specific exercise plan for children who have asthma, and offer no time frame or intensity on the amount of exercise a child should do .They say it is appropriate to advise these patients regarding the precautions of exercise induced asthma and how to manage this (NICE, 2016b). Again this is a area in which the NICE guidelines could seek to improve by developing guidelines on the recommended timing and intensity of exercise for children with asthma.

Section 3: The Role of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

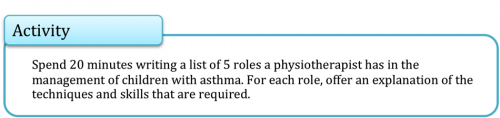

Physiotherapists have a wide intervention scope for children with asthma however numerous newly-qualified physiotherapists are unaware of their extensive role for the management of respiratory conditions in children.

Prior to reading the description of the various roles of the physiotherapist in the management of children with asthma, complete the quiz presented below to understand your baseline knowledge:

It is noted that the abovementioned guidelines in Section 2 for managing asthma in children make no mention of the role of the physiotherapist as a member of the asthma symptom management team; it only emphasises the importance of pharmacological interventions. However, there is much that physiotherapy can offer in the way of asthma symptom management in children.

The following table shows the roles of physiotherapists with children with asthma:

Increasing awareness of the condition[edit | edit source]

Increasing awareness about the nature of the condition including pathophysiology, asthma triggers and the progression of the condition with/without effective management. Details about the condition and its progression have been outlined in the previous sections of the page however it is the physiotherapist’s responsibility to adapt the information delivered depending on the age of the child as well as parental anxiety so as to not overload with information but at the same time deliver enough useful information.

Subjective Assessment [edit | edit source]

A diagnosis of asthma can be comfirmed based on various factors and symptoms. The patient is asked to explain their various symptoms, it is also important to hear the parents explain how they interpret the symptoms. You should as the patient to describe the frequency,duration and aggrivating factors of their symptoms. It is important as a physiotherapist to know is they have been exposed to chemical fumes, dust or tobacco smoke as this might lead to the onset of asthmatic symptoms.It is also helpful to ask is their any family history of asthma or allergies as this makes the child more likely to be suffering asthmatic symptoms. While there is an increased risk of children of having asthma if their is a family link, it is believed that over 100 genes may be related to asthma and individual effect of any one of these genes on disease risk is quite small. Research is still being conducted to establish the genetic link in herediary asthma (Ober and Hoffjan 2006)

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

When carrying out a subjective assessment for a child with asthma it is important to find out the child’s opinion on he’s symptoms and the severity if they are able to communicate and the parent or guardians view on their symptoms.

Frequent, intermittent coughing – Children can have a persistent cough with an intermittent onset. If noticed by a parent It should be investigated. The child can also suffer from bouts of coughing which get worse when the child has respiratory infection (Rubin et al. 1998)

Wheezing sound when exhaling – Children often present with a wheezing sound on exhalation. This is a strong indication of asthma that may persist throughout childhood and adult life (Sears et al. 2003).

Shortness of Breath - Struggling for breath even at rest and low levels of activity can be a symptom of asthma in children. Heavy and harsh breathing sounds are symptoms parents should look out for.

Fatigue – Asthma can cause children to sleep poorly, this can cause children to appear tired during the day even after having a full night’s sleep. This can affect performance and behaviour in school as well (Fagnano et al. 2011).

Chest pains & tightness – chest pains are particularly prevalent in younger children with asthma. Chest tightness can be accompanied by shortness of breath (Anas 2007).

What do patients and parents know about asthma?[edit | edit source]

Medicine aspect – One study found that parents found it difficult to why doctors changed medication doses. It was felt that this was due to delayed diagnoses. The study also concluded that listening to parents opinions and including parent participation is important in regulating drug dose according to the symptoms ,to secure the lowest possible but effective drug dose (Ostergaard 1998)… Another study found that almost half of parents were using the asthma inhaler for cough medication than for its proper use. It also found that only 13% were administering aerosol therapy at home (Shivbalan et al. 2005).

Attitudes of asthma - Studies carried out find that generally parents have a poor understanding of asthma. A sample of 100 parents were asked about their attitude towards there childs asthma with only 39% accepting the diagnosis and only 3 out of 100 knew exactly what asthma is. 26% of the parent also believed asthma was contagious and 35% believed asthma was a hereditary disease. However, this was a relatively small study size carried out on a homogenous population in India (Shivbalan et al. 2005) In another study it was pointed out that patients and parent felt that doctors didn’t’t pay enough attention to them describe symptoms and relied more on auscultations. Which was felt to contribute to a poor mutual understanding. The study also found that parents can recognise specific asthma patterns in their child often including behavioural changes. However, this was a study which included 30 children and 20 parents. Studies have also shown that parent can tend to overestimate the severity of their child’s asthma. This can have a negative effect on the treatment process (Silva and Barros 2013).

SILVA, C. M. and BARROS, L., 2013. Asthma knowledge, subjective assessment of severity and symptom perception in parents of children with asthma. Journal of Asthma. August, vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 1002–1009.

ANAS, N. G., 2007. Pediatric hospital medicine: Textbook of inpatient management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. P191

OBER, C. and HOFFJAN, S., 2006. Asthma genetics 2006: The long and winding road to gene discovery. Genes and Immunity. January, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 95–100.

OSTERGAARD, M. S., 1998. Childhood asthma: Parents’ perspective--a qualitative interview study. Family Practice. April, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 153–157.

SHIVBALAN, S., BALASUBRAMANIAN, S. and ANANDNATHAN, K., 2005. What Do Parents of Asthmatic Children Know About Asthma?: An Indian Perspective. Indian J Crest Dis Allied Sci. April, vol. 81, no. 7, pp. 81–88.

SEARS, M. R., GREENE, J. M., WILLAN, A. R., WIECEK, E. M., TAYLOR, D. R., FLANNERY, E. M., COWAN, J. O., HERBISON, G. P., SILVA, P. A. and POULTON, R., 2003. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. October, vol. 349, no. 15, pp. 1414–1422.

RUBIN, B. K., NEWHOUSE, M. T. and BARNES, P. J., 1998. Conquering childhood asthma an illustrated guide to understanding the treatment and control of childhood asthma. Hamilton, Ont.: Empowering Press. P8

FAGNANO, M., BAYER, A. L., ISENSEE, C. A., HERNANDEZ, T. and HALTERMAN, J. S., 2011. Nocturnal asthma symptoms and poor sleep quality among urban school children with asthma. Academic Pediatrics. November, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 493–499.

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

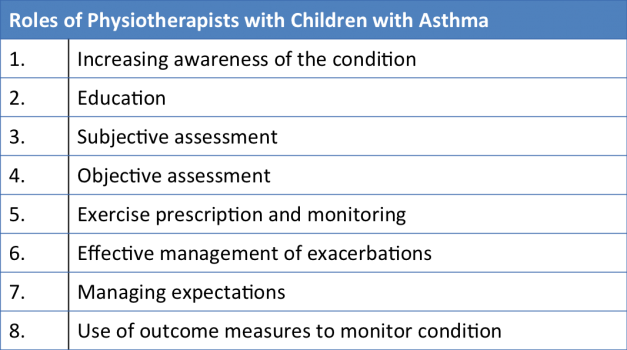

Vital signs taking[edit | edit source]

- Heart rate (HR)

- Blood pressure (BP)

- Respiratory rate (RR)

- Oxygen saturation (SpO2)

- Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF)

The video below shows how to use a peak flow meter and the table below shows normal paediatri values for respiratory rate, heart rate and systolic blood pressure:

Table 3. Normal Paediatric Values

Inspection[edit | edit source]

General appearance

- Posture

- Sitting upright or tripod position - Nasal flaring

- Breathlessness in speech (assessing if the child can complete sentences in one breath)

- Cyanosis

Breathing

- Retractions: Indrawing of skin

- Suprasternal (Trachela tug): Middle of neck above sternum

- Substernal: Abdomen below sternum

- Intercostal: Skin between each rib

- Subcostal: Abdomen below rib cage

- Supraclavicular: Neck above collarbone - Use of accessory muscles

- Sternocleidomastoid

- Parasternal

- Scalene

- Trapezius - Thoracic/Shallow breathing

- Paradoxical chest wall movement: Inward movement on inspiration and outward movement on expiration

Chest wall configuration

- Barrel-shaped

- Anteroposterior diameter (May increase due to hyperinflation)

Cough (and sputum)

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Scalene muscle contraction

Symmetry of chest movement

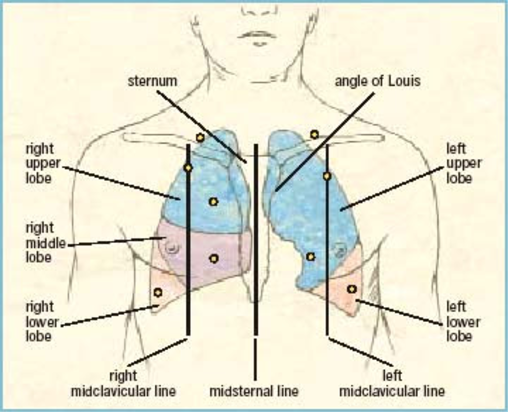

Auscultation[edit | edit source]

Lung fields

- Right anterior lung field (RUL & RML)

- Right posterior lung field (RUL & RLL)

- Left anterior lung field (LUL & LLL)

- Left posterior lung field (LUL & LLL)

The below image shows the lung anatomy:

Figure

Wheezing

Polyphonic, widespread, high-pitched

The below link includes an audio file which allows you to hear what a characteristic wheeze sounds like during the auscultation phase of an objective assessment:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asthma

Coarse crackles

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Asthma Control Test (ACT)[edit | edit source]

The ACT was developed as a tool to identify patients with poorly controlled asthma. It is a short, simple questionnaire that patients can do themselves to identify if their asthma may be poorly controlled. The questionnaire is age specific as they have a questionnaire with facial expressions aimed at kids 4 to 11 which makes it easier for them to identify their symptoms. Another asthma control test is aimed at children 12 years and older. A score of 19 or less identifies patients with poorly controlled asthma. The ACT has been shown to be reliable and responsive to changes in asthma management in patients (Kennedy and Jones 2007).

Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children (PAQ-C) and Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAR-A)[edit | edit source]

The PAQ-C and the PAQ-A are validated self-report measures of physical activity widely used to assess physical activity in children aged 8-14 and 14-20 respectively (Kowalski et al. 2005). Both and PAR-C and PAQ-A are self administered tests, measuring general moderate to vigorous physical activity levels. It is a low cost, reliable and valid assessment of physical activity from childhood through adolescence (Kowalski et al. 2005).

Paediatric Asthma Quality of life Questionnaire (PAQLQ)[edit | edit source]

The PAQLQ is a health-related quality of life assessment that can provide an idea of the functional impairments (Physical, emotional and social) of the paediatric patient that are important to the patients in their everyday lives (Juniper et al. 1997). The Paediatric Asthma Quality of life questionnaire (PAQLQ) is targeted for children aged 7-17 years and has 23 questions in 3 areas (Symptoms, activity limitation and emotional function). The activity domain contains ‘patient-specific’ questions. Children are asked to think about how they have been during the previous week and to respond to each of the 32 questions on a 7-point scale (7= not bothered at all- 1= extremely bothered) (Juniper et al. 1997). Calculation of the results involves taking the mean of all the 23 responses and the individual domain scores are the means of the items in those domains (Juniper et al. 1997).

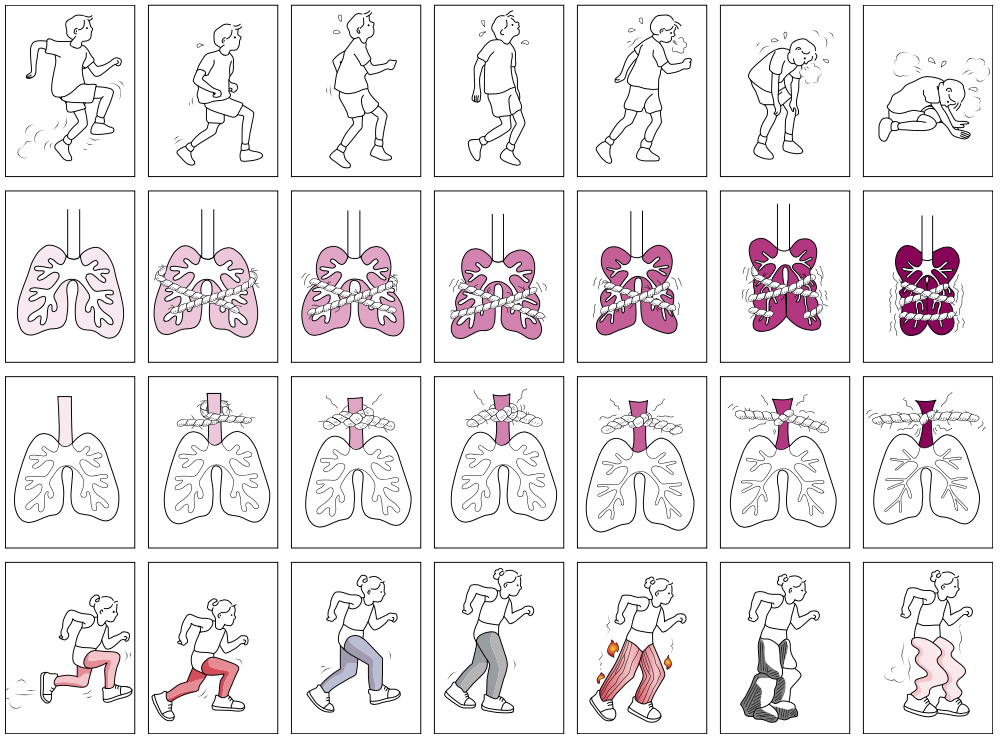

Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale[edit | edit source]

The Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale is a pictorial scale that encompass the full range of the perception of breathlessness by children (McGrath et al. 2005).

Areas tested:

· Breathing effort

· Chest tightness

· Throat closure

The image below shows 7 pictures which are used with increasing severity in each series (Pianosi et al. 2015). This scale has been validated against the Perceived Exertion Scale in children 7 years or older with asthma or cyctic fibrosis.

Pianosi P T, Huebner M, Zhang Z, Turchetta A, Mcgrath, P. J. Dalhousie pictorial scales measuring Dyspnea and perceived exertion during exercise for children and adolescents. The Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015; 12(5):718-726. Available from: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-477OC [Accessed 10th January 2017].

Paediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM)[edit | edit source]

The PRAM is a valid and reliable objective assessment of asthma severity for children aged 2-17 years with acute asthma (Ducharme et al. 2008). It is tested on a 12-point scale for 5 different areas (O2 saturation, suprasternal retraction, scalene muscle contraction, air entry and wheezing) (Ducharme et al. 2008).

3-hour PRAM scores can be used in clinical settings to facilitate the decision to admit or initiate more aggressive adjunctive therapy to decrease the need for hospitalization (Alnaji et al. 2014).

Section 4: Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Exercise prescription [edit | edit source]

F.I.T.T

Effective management of exacerbations[edit | edit source]

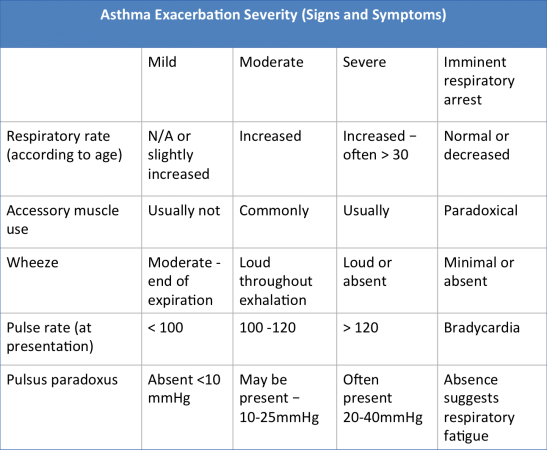

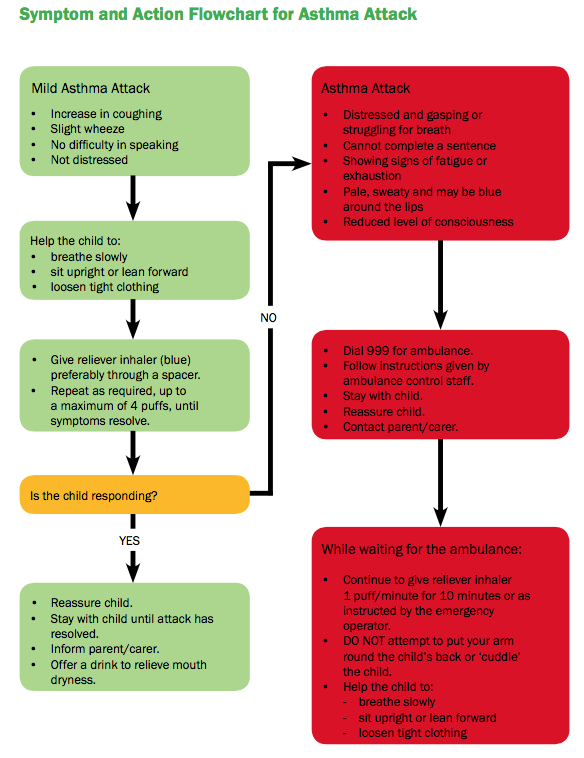

Management of exacerbations. Asthma exacerbations in children can be categorized depending on severity and the demonstration of specific signs. It can be useful for the physiotherapist to be informed about signs of previous exacerbations so as to monitor the progression of the child’s asthma.

The table below is a useful guidance tool for asthma exacerbation severity:

(Kumar, 2014)

Patient education and self-management[edit | edit source]

Delivering education to the affected child themselves, their family and their school especially in regards to participation in physical activity. Studies suggest that physical activity improves cardiopulmonary function without compromising lung function and does not have an adverse effect on wheeze for children with asthma (Ram et al. 2005). Respiratory education for the child includes secretion clearance techniques, strengthening of the respiratory muscles and specifically timed inspirations and expirations can act as exacerbation preventative therapy. Interestingly, through respiratory education, the oxygenation of the brain is enhanced which has been shown to translate into improved academic performance and improved quality of life (Valdivia 2009).

Asthma education is important in the child, parent and teachers. Asthma education for children can promote active involvement and facilitation of learning from other’s shared experiences, leading to improved confidence in their own strength and empowerment, as well as their sense of coherence (SOC) in managing their own condition (Trollvik et al. 2013). However, educating the child with asthma about the feasibility and benefits of physical activity will not be effective if the family and school contexts are not also persuaded to encourage and facilitate participation (Coleman et al. 2001; Williams et al. 2008). Parents and teachers also need to be educated on how and when children with asthma can participate in physical activity, how to adjust medication before and during periods of extended activity and how to differentiate between limitations at times of asthma exacerbation and overall limitations (Mansour et al. 2000).

Breathing techniques[edit | edit source]

A common sign of poorly managed asthma in children is superficial/clavicular breathing. In this type of breathing, expansion of the chest only occurs around the height of the clavicles upon inspiration, the neck muscles pull the first 2 ribs in an upward direction and the diaphragm and abdomen hardly intervene. The inefficiency of this breathing pattern due to its high energy expenditure for minimal gaseous exchange makes it a perfect starting point for respiratory education to introduce lateral, deeper breathing.

Studies suggests that cardiovascular endurance conditioning should be the key aspect of the physical activity a child with asthma receives (Villa et al. 2011). Respiratory exercises enhance exercise tolerance and help build resistance against muscle fatigue. Balloon blowing; cotton-wool straw football exercises are excellent examples of games which are fun for children and simultaneously increase lung volume and improve gaseous exchange to improve quality of life in a relatively controlled manner (Thomas et al. 2009).

Correct Inhaler Use[edit | edit source]

Proper inhaler use is vital to the good management of asthma in children. It is estimated that up to 25% of asthma sufferers use improper inhaler technique (Bernstein 2014). Improper inhaler uses has proven to correlate with poor asthma control and more frequent emergency hospital visits (AL-Jahdali et al. 2013). Poor technique is also associated with a lower quality of life and level of patient education is associated with poor inhaler technique (Hashmi et al. 2012). As a result, correct inhaler technique is vital in the management of children with asthma exercising and physiotherapists should be able to properly demonstrate inhaler techniques.

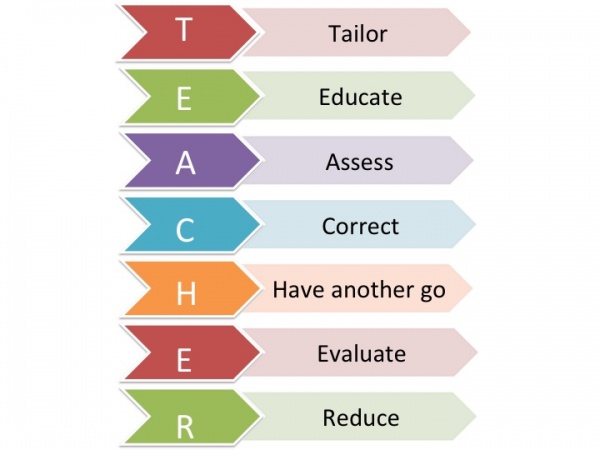

The T.E.A.C.H.E.R acronym is a great way to ensure children are in receipt of the correct care, and that their programme is tailored specifically to them. The figure below shows what the acronym stands for:

Tailor – Tailor the method of delivery to suit your patient. Many younger children especially ones younger than 5 years old have difficulty timing breathing with the inhaler and a spacer is often used to remedy this problem. Children who have shallow patterns of breathing my also find using an inhaler difficult and benefit from using a spacer

Educate - Educate the child in the correct timing of when to trigger the inhaler and how to take a deep breath. Explain to the child the importance of using the inhaler and why having correct technique is vital.

Assess – Assess the patients technique, allow them to attempt using the inhaler independently without prompts. Focus on the timing of triggering the inhaler with their breathing. Pay close attention to any mistakes.

(Figure . TEACHER Technique)

Correct – After assessing the patients technique, correct the patient on any mistakes they may have made. Re enforce the areas in which their technique was successful and correct areas in which they need to improve.

Have Another go – Re assess the patients technique and see if it has improved after correction.

Evalute – Evaluate the childs technique and see it is of an adequate standard. If not correct and re assess again.

Reduce – Children are recommended to use their inhaler 15 minutes before physical activity and during in case of an attack. In general use a patient should be recommended to use the inhaler as conservatively as possible. Health care professionals should recommend reduction in inhaler usage if possible.

Safe breathlessness[edit | edit source]

As breathlessness is very subjective and can vary from person to person, choosing a point of safe breathlessness is very much down to the individual. There are no guidelines to determine what is classed as safe breathlessness, therefore parents, teachers, family members and clinicians must take a very subjective approach to this. Children should be encouraged to exercise, but stop if breathlessness gets worse than their perceived normal level. When completing a subjective assessment on a child with Asthma, a visual breathlessness scale should be used to aid children with where they sit on the scale, similar to a VAS scale for pain (Hawker et al. 2011). The Dalhousie Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale (McGrath et al. 2005) is an example of this - as shown in our section regarding outcome measures - and allows the child to pick where they think they are on the scale to determine their level of breathlessness.

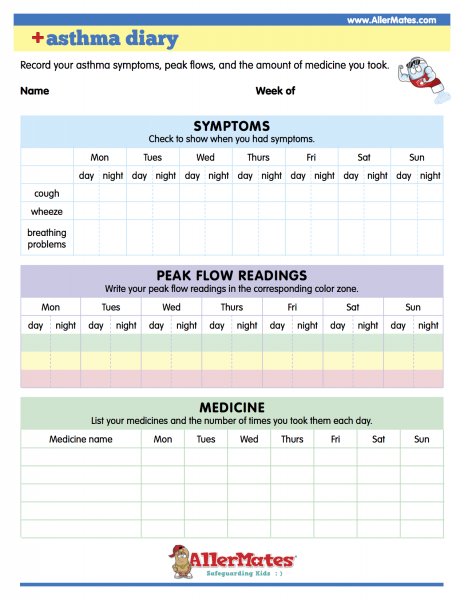

Asthma Diary[edit | edit source]

Effective management of your asthma is not solely based on administering the correct medication at the correct times and dosage. This is of course one of the most important aspects in order to keep your asthma well controlled, but by no means the only option. Asthma is an extremely variable condition and no two people’s asthma is likely to be identical. This emphasises the importance of education being an integral aspect of all interactions between the health care professionals and patients, and relevant to asthma patient’s of all ages. Although the focus of education for young children will predominantly be on the caregivers and parents, children as young as 3 years old can be educated on simple asthma management skills and personal triggers. Research by (Shah et al. 2001. Trollvik et al. 2013) showed that although adolescents may have some degree of difficulty in adhering to asthma education, this could be enhanced through peer support group education with the added support of education given by the health care professional.

Management can be made easier by the application of an Asthma Diary, which can be made as simple or detailed as you require. However, the more detailed the information is the more beneficial it will be, not only for your child but also the asthma nurse or doctor, who can systematically tailor your treatment to your needs. Identification of what triggers your child’s asthma can sometimes be easily identifiable, however at times it can be complex, therefore keeping a daily asthma diary could help.

The asthma diary (shown to the left) includes a record of:

• Symptoms

This would be beneficial to keep a record, so you can monitor whether your symptoms get better or worse over time. Recording the time when symptoms are worse and what triggered them would be of great benefit so measures can be undertaken to address these issues.

If you notice any of the following symptoms such as:

• Frequent waking throughout the night suffering from excessive coughing, wheezing and shortness of breath.

• Administration of the reliever treatment at a much greater rate than normal, or if this doesn’t seem to be working in any way.

• Upon wakening in the morning, you suffer from shortness of breath.

• Finding it increasingly difficult to participate in your usual level of activity.

Then the most important thing is to phone your doctor who can administer the correct treatment, which can help you bring your child’s asthma back under control.

• Peak Flow Readings

The peak expiratory flow measurements are made using a peak flow meter (PEF), which can be important in the diagnosis and monitoring of asthma. Modern PEF meters are relatively inexpensive, portable, plastic and ideal for children to use in the home setting for day-to-day objective measurements of airflow limitation.

The PEF is a measure of the highest expiratory flow that can be generated following the child’s maximal inspiration. The reading will directly be influenced by airway diameter and can be a useful indication of the degree of bronchoconstriction in asthma sufferers (Main and Dehehy. 2016).

• Medication

This is extremely important to record both the various forms of medication the child takes and also the timeframe the medication was administered. This also includes any other types of medication they use, such as over the counter remedies.

This information will allow the doctor or practice nurse to monitor how well controlled the child’s asthma is and how effective the medication is in controlling the asthma symptoms. Therefore, clinical decisions can be made whether to change, increase or decrease the medication to gain or maintain control (Ludman et al. 2016).

The asthma diary would also benefit from the recording of the child’s participation in daily activities and the effect these have on asthma symptoms. For example, the child may feel their asthma is well controlled but notice some degree of difficulty when participating in certain exercise or even running for the school bus. Recording of this information will allow your doctor or asthma nurse to generate a written self-management action plan, which is tailored to your child’s needs. According to the SIGN (2016) guidelines on the management of asthma, all patients of all ages should be offered self-management education, which should also include the development of a personalised asthma action plan. Research has shown that symptom-based written plans for children are effective in reducing emergency consultations (Bhogal et al. 2006 and Zemek et al. 2008).

Asthma Action Plan[edit | edit source]

Bronchodilators: The Correct Use[edit | edit source]

How to Use a Metered-Dose Inhaler "Puffer"

A metered-dose inhaler, called an MDI for short, is a pressurized inhaler that delivers medication by using a propellant spray.

To use a Puffer:

1. Shake the inhaler well before use (3 or 4 shakes)

2. Remove the cap

3.Breathe out, away from your inhaler

4.Bring the inhaler to your mouth. Place it in your mouth between your teeth and close you mouth around it.

5.Start to breathe in slowly. Press the top of you inhaler once and keep breathing in slowly until you have taken a full breath.

6.Remove the inhaler from your mouth, and hold your breath for about 10 seconds, then breathe out.

If you need a second puff, wait 30 seconds, shake your inhaler again, and repeat steps 3-6. After you've used your MDI, rinse out your mouth and record the number of doses taken. All puffers should be stored at room temperature.

Important Reminders About MDIs

Always follow the instructions that come with your MDI.

Also:

- Keep your reliever MDI somewhere where you can get it quickly if you need it, but out of children's reach.

- Show your doctor, pharmacist or asthma educator how you're using your metered-dose inhaler.

- Store your MDI at room temperature. If it gets cold, warm it using only your hands.

- Never puncture or break the canister, or try to warm it using anything except your hands.

- When you begin using an MDI, write the start date on the canister.

- Check the expiry date on the MDI before you use it.

- If you're having trouble using your MDI, ask your doctor for tips or to recommend another device.

- Many doctors recommend the use of a spacer, or a holding device to be used with the MDI.

- Do not float the canister in water.

Ref --- http://www.asthma.ca/adults/treatment/meteredDoseInhaler.php

The video below shows how to use an asthma inhaler correctly:

How to use unhaler with a spacer - step by step description and video embedded

The image below shows the correct use of an inhaler with a spacer for a child:

To Use a Spacer:

1.Shake the inhaler well before use (3-4 shakes)

2.Remove the cap from your inhaler, and from your spacer, if it has one

3.Put the inhaler into the spacer

4.Breathe out, away from the spacer

5.Bring the spacer to your mouth, put the mouthpiece between your teeth and close your lips around it

6.Press the top of your inhaler once

7.Breathe in very slowly until you have taken a full breath. If you hear a whistle sound, you are breathing in too fast. Slowly breath in.

8.Hold your breath for about ten seconds, then breath out.

Important Reminders About Spacers

- Always follow the instructions that come with your spacer. As well:

- Only use your spacer with a pressurized inhaler, not with a dry-powder inhaler.

- Spray only one puff into a spacer at a time.

- Use your spacer as soon as you've sprayed a puff into it.

- Never let anyone else use your spacer.

- Keep your spacer away from heat sources.

- If your spacer has a valve that is damaged, or if any other part of the spacer is damaged, do not use it. The spacer will have to be replaced.

- Some spacers have a whistle. Your technique is fine if you do not hear the whistle. However, if you hear the whistle, this means you should slow your breath down

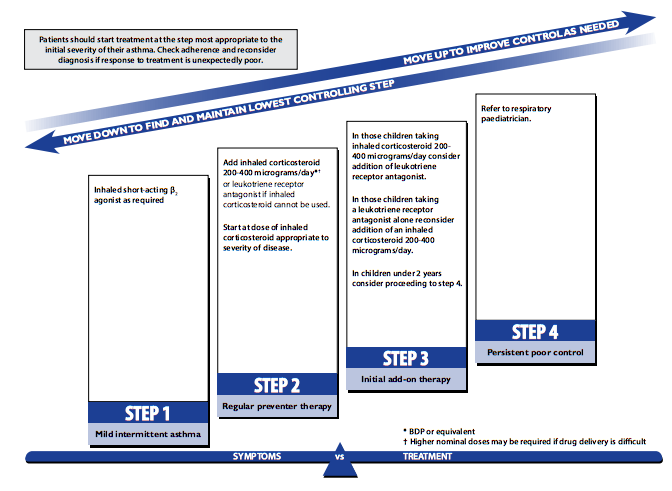

The image below shows a five-step process of controlling asthma for children aged less than 5 years:

Figure For children less than 5

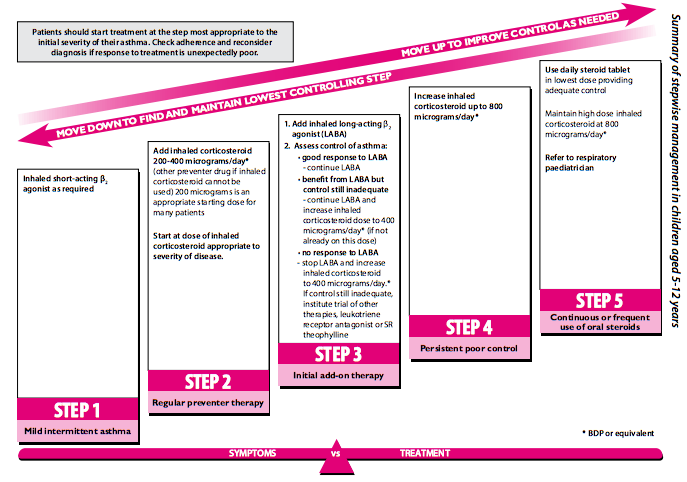

The image below shows a five-step process of controlling asthma for children aged between 5-12 years:

Figure For children aged 5-12

Ref = http://www.asthma.ca/adults/treatment/meteredDoseInhaler.php

The video below is a children's guide on how to use a spacer:

BERNSTEIN, J. A., 2014. Clinical Asthma: Theory and Practice. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC press.

P130

AL-JAHDALI, H., AHMED, A., AL-HARBI, A., KHAN, M., BAHAROON, S., BIN SALIH, S., HALWANI, R. and AL-MUHSEN, S., 2013. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. vol. 9, no. 1, p. 8.

HASHMI, A., SOOMRO, J. A., MEMON, A. and SOOMRO, T. K., 2012. Incorrect Inhaler technique compromising quality of life of Asthmatic patients. Journal of Medicine. March, vol. 13, no. 1,

Managing expectations[edit | edit source]

Managing expectations, which refers to both the child’s expectations at the moment of the diagnosis and as they get older, but also the expectations of the child’s parents in respect to asthma progression, participation in physical activity and understanding their role in asthma management.

Health Promotion[edit | edit source]

Recommended Physical Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Children with asthma should be encouraged to lead a healthy, active lifestyle. While it is well known that healthy children should perform at least 60 minutes of physical activity a day, the same physical activity recommendations also applies to children with asthma (Longmuir et al. 2014). Adjustments or restrictions however, to the frequency, intensity, duration, or type of physical activity permitted for each child should be appropriately done so to reduce the risk of a physical activity-related adverse event (Bar-Or and Rowland 2004). Children with asthma should use inhaled β-2 agonists 15-30 minutes prior to beginning exercise (Riner and Sellhorst 2013), and do adequate warm up exercises to reduce asthmatic symptoms especially during cold weather (Asthma UK 2016).

Considerations for Children with Asthma[edit | edit source]

The image above shows a symptom and action flowchart for asthma exacerbations.

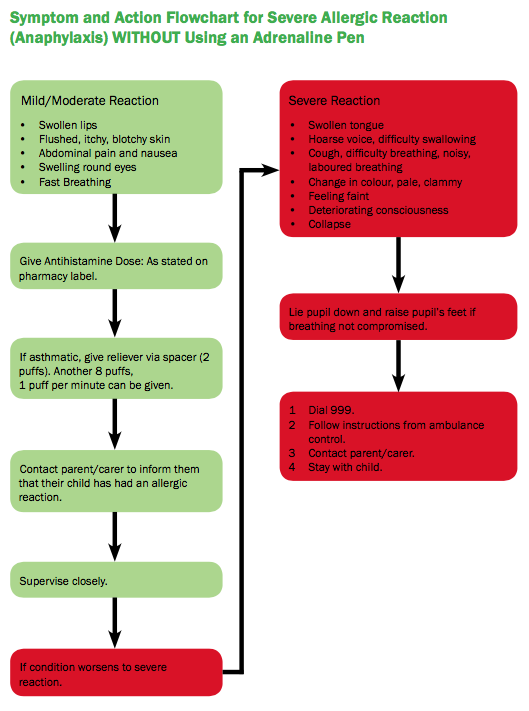

The image below shows a syptom and action flowchart for anaphylaxis without using an adrenaline plan:

Figure

Evidence Based[edit | edit source]

Respiro Initiative Barcelona[edit | edit source]

The Respiro Initiative is a project that began in 2008 in Barcelona<ref name="Buddy2015">Buddy (2015. Blah blah blah.</ref>. The key features of the project are outlined below:

Physiotherapists delivered a breathing exercise program for deprived children in unfavoured economic districts with limited previous access to community physiotherapists. The breathing exercises were adapted for participants of different age groups. Children under the age of 2 were treated with respiratory physiotherapy (including percussion, vibrations, manual AD holds). Children aged between 3-10 were taught breathing games which enhance the efficient use of respiratory musculature while children over the age of 10 were assigned conscious breathing control exercises.

*Numerous exercises involving deep breathing and controlled breathing were presented to children in a fun environment and an educational component involving awareness about safe physical activity and health promotion was also included for the children and their families (Shenfield et al. 2002).

*This initiative<ref name="Buddy2015" /> can be directly replicated in other countries and has the other main advantage of tackling the poor adherence demonstrated by children with asthma towards any form of symptom management intervention due to its play-based nature.

*As highlighted above, the physiotherapists role in current management of children with asthma is to enhance community based care while incorporating health promotion. This can be done on a relatively large scale through initiatives such as Respiro or on a smaller scale such as education at local schools.

For more information about the Respiro initiative in Barcelona please visit:

www. fundrogertorne.org/health-childhood-environmental/2011/09/07/respiro-open-doors-day-first-appointment-for-childrens-health-during-the-school-year/

Case Study[edit | edit source]

D.C. is a 9-year-old boy with asthma who presents to the Accident and Emergency (A&E) with respiratory distress, cough and troubled breathing due to an acute asthma exacerbation. This episode began 3 days ago when initial fever-like symptoms began. The child’s mother also suffered with upper respiratory infections recently and has been treating the child with subutamol via nebuliser every 4 hours. Despite this initial treatment, he is becoming increasingly short of breath this evening prior to the admission to the A&E. In the last 24 hours, his mother has noticed a gradual cyanosis on the child’s face.

On assessment of past medical history, it is noticed that D.C. has asthma since infancy and has multiple family members suffering from asthma. Regarding social history, his mother explains that he is in year 4, has missed numerous days of school in the past month due to his asthma, and has not been performing his breathing exercises frequently for the last 6 months. His current medication is subutamol. D.C. is rarely motivated to exercise and seems confused about the correct use of the inhaler.

On physical examination, he was unable to talk in long full sentences without stopping to breathe and appears in severe respiratory distress, with paradoxical breathing and tracheal tug. His vital signs are temperature of 38.0 degrees celsius, respiratory rate of 28, heart rate of 120, and a Systolic BP of 110, oxygen saturation of 93% on room air and peak flow of 195 L/min (Height 1.30m). Upon auscultation, a diffused symmetrical wheeze is noticed, a prolonged expiratory phase and reduced air entry in the right lower zone. Upon coughing, he produced copious amounts of clear sputum, skin is dry, however the remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

1) What severity classification would you assign to D.C?

2) What indication are there that D.C. is suffering from an asthma exacerbation?

3) Identify his physiotherapy problems list

4) Based on the physiotherapy problems list, create a set of patient centered goals for D.C.

5) What kind of outcome measures will you use for D.C.?

6) Formulate a treatment plan based on the goals and problems list

Answers:

1) Moderate severity

2) Wheezing

Shortness of breath

Tracheal tug

Cough and sputum

Difficulty breathing

3) Answer:

Shortness of breath

Reduced air entry in the right lower zone

Decrease peak expiratory flow

4) Answer:

Able to talk in full sentences without having to pause due to shortness of breath in 1 day

Clear breath sounds upon auscultation in 2 days

Increase peak expiratory flow within normal range within 3 days

5) Answer:

Asthma control test

PAR-C

PAQLQ

Dalhouse Dyspnea and perceived exertion scale

PRAM

6) Answer:

Breathing exercises: peak flow

Education: correct inhaler use

Exercise prescription:

Quiz[edit | edit source]

1) How many children diagnosed with asthma were living Scotland in 2016?

a. 2000

b. 72000

c. 94000

d. 133000

2) How many minutes per day should children aged 5-17 participate in moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity?

a. 30 minutes

b. 45 minutes

c. 60 minutes

d. 120 minutes

3) Are children in Scotland currently meeting the physical activity recommendations?

a. Yes

b. No

4) Which ones of these are not perceived barriers to physical activity?

a. Housework

b. Beliefs of the child

c. School environment

d. Parental support

5) Which of these are signs and symptoms of a 4 year old child with severe asthma attack?

a. Cyanosis

b. Too breathless to talk

c. Loud chest upon auscultation

d. All of the above

6) Which of the following is not one of the physiotherapist's role in managing asthma?

a. Health promotion

b. Exercise prescription

c. Medication prescription

d. Managing expectations

Answers:

1. B

2. C

3. B (Only 27% meeting physical activity)

4. A

5. A

6. C

Reflection[edit | edit source]

Write a 500 word reflection

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Thank you for completing this online resource, we hope that you’ve found it useful and that this has helped you developed your knowledge in managing children with asthma. This learning resource is a great starting point however, further training may be required prior to treating children with asthma.

From the 5 learning outcomes of this learning resource, you should now be able to outline the impact of asthma on a child using the ICF Model, analyse the current barriers to physiotherapy, and now suggest ways to overcome them. Furthermore, you should be able to analyse the skills and attributes that a physiotherapist should demonstrate when managing asthma in children using current evidence based guidelines. Finally, you should now confidently be able to design an individualised treatment plan for a child aged 0-18 with asthma.

Physiotherapists can play a significant role in managing asthma despite the lack of evidence focused at paediatric population. Children with asthma can demonstrate a plethora of symptoms which should be identifiable with the physiotherapist. However, further research is required to further our understanding of the condition and it’s ideal management.

Now that you've completed the online resource, we hope that you have found value in the case study, quiz and fulfilling the final reflection. Feel free to revisit any other section of the resource prior to completing the final activity. Take this moment to review the learning outcomes presented in the beginning of the resource and assess how well you feel you have achieved them. Take into consideration what actions you can take to enhance your learning and further support your clinical practice in the future.

Support Group[edit | edit source]

Asthma UK

Asthma UK is a Registered Charity in England and Wales No. 802364.

Helpline: 0300 222 5800

Email: [email protected]

http://www.asthma.org.uk

British Lung Foundation

British Lung Foundation is a Registered charity in England and Wales (326730), Scotland (038415) and th Isle of Man (1177).

Helpline: 0207 688 5555 OR 03000 030 555

Write to them: 73-75 Goswell Roal, London EC1V 7ER

https://www.blf.org.uk/get-in-touch

References[edit | edit source]

<references/>

</div>