Paediatric Conditions of the Foot

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (31/10/2023)

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Optional reading: for an in-depth review of foot structure and functional anatomy, please read this article.

Metatarsus Adductus (Metatarsus Varus)[edit | edit source]

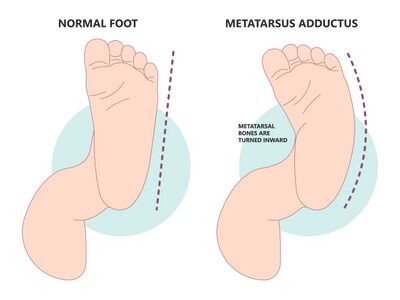

"Metatarsus adductus primarily involves medial deviation of the forefoot on the hindfoot." - Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSAN)[1]

Secondary characteristics include:

- prominence of the 5th metatarsal base [1]

- neutral[2] to slightly valgus hindfoot [1]

- slightly supinated forefoot [1]

- a possible widening of the space between the 1st and 2nd toes [1]

- many patients also have internal tibial torsion [1]

- no ankle range of motion (ROM) restrictions [2]

Metatarsus Adductus can be divided into two types:

- Flexible: Presents with adduction of the 5 metatarsal bones at the tarsometatarsal joint.

- Rigid: Presents with medial subluxation of the tarsometatarsal joints. There is valgus of the hindfoot and the navicular is later to the head of the talus.

Incidence: 1/1,000 live births [1][2]

Etiology:

- In utero compression

- Embryologic or congenital abnormalities [2]

Assessment:[edit | edit source]

- Bleck’s Heel bisector line (HBL) is a simple measure that assesses the flexibility and severity of metatarsus adductus. It is a manual assessment and no types of equipment is needed.

- Procedure:

- This method has been used for over four decades, with some modifications. Traditionally a mould of the weight-bearing foot is made so as to obtain an ellipse at the heel. Modifications include the use of footprints or photos the weight-bearing foot.[3] Another option includes placing the child in prone with their knees flexed to 90°, with the plantar surface of the foot parallel to the ceiling.[2]

- Next, the procedure is completed by determining the longitudinal axis of the ellipse with a straight edge, independent of the forefoot.[3]

- Classification of metatarsus adductus according to Bleck’s classification involves observation of where the JBL crosses the metatarsal heads.[3]

- Procedure:

| Classification | Measurement finding |

|---|---|

| Normal | Heel bisector line through 2nd and 3rd toe webspace |

| Mild | Heel bisector line through 2nd and 3rd toe webspace |

| Moderate | Heel bisector line through 2nd and 3rd toe webspace |

| Severe | Heel bisector line through 2nd and 3rd toe webspace |

- Heel bisector method, and this really looks at how much that forefoot is pointing inwards. So to do this, what you do is you have the child in prone with their knees flexed to 90, similar position to where we've had them for a lot of our other assessments. You're going to have the plantar surface of the foot parallel to the ceiling or the floor or the mat or whatever they're sitting on, and then you're going to draw a line visually down to bisect through the heel. And what you're going to look for is where that line continues on. So you bisect the heel, if that line continues straight and bisects between the second and the third web space. So between those second and third toes, that's normal. This is where we would anticipate that a foot should align. If they have mild metatarsus adductus, what you will see is that that line goes through the third toe. Moderate is when that line goes through the third and the fourth web space and severe is when the line goes through the fourth and the fifth web space.

- You also want to check how flexible this metatarsus adductus is. So how severe is it and how flexible is it? So what you want to do to assess flexibility is apply a lateral force to the great toe to reduce the foot back to that bisector line. So can you get that foot to go back to a midline position so that that bisector line would go through that second toe? Based on the flexibility, it gives us some idea of what we need to do for treatment and management. So if you have a flexible foot that you can correct beyond midline, we give that that grade one. If it's moderately flexible with the ability to correct to midline, we give it a grade two and a severe is a three with an inability to correct to midline.

Transmalleolar Axis Bisector (TMAB)

Intervention:

So for mild cases, this typically resolves without intervention. For moderate cases, you can try stretching exercises and you can try corrective shoes. So we have this straight or reverse last. So when we talk about a last with shoes, what we're talking about is the natural curve that you see in a shoe. So most shoes actually have a last. That does have the forefoot point inwards a little bit. So if you look at the bottom of your shoe, you can see that there is this kind of curve of the shoe. Now what you can do is you can actually put the baby's shoes or the child's shoes on the opposite feet because the outside part of the shoe is often fairly straight. So when you have the shoes on opposite feet, you're going to have this kind of straight line that helps to force that foot back into a midline position and hold it there. And then a reverse last is really where the shoe would actually curve towards the outside, towards the pinky toe just a little bit rather than the normal wear shoe does tend to naturally kind of curve inwards towards the big toe just a little bit. Severe cases might need manipulation of the bones, they might need serial casting, and then corrective shoe wear. Surgery is definitely not considered for these children before ages of four because again, you want to allow for spontaneous resolution that could happen throughout typical development with all of those nice ground reaction forces that they would get through just the normal movements that they would do day to day.

Pes Planus (flat foot)[edit | edit source]

Definition: So with pes planus, what we see is that medial longitudinal arch of the foot really stays really flat. So whenever we're born, we don't have that medial longitudinal arch that's present. That area of the arch that's there is really just fatty tissue and that arch starts to develop in that first decade of life. And a lot of times we see a really big progression of that arch from about two to six years old. The most common cases that we'll have for having this flat foot position that persists is due to ligamentous laxity. But some things can actually encourage a more flat foot. So sometimes we'll see this in children who wore closed toed shoes rather than open shoes or no shoes. And that's really because when you're in a shoe, your foot intrinsics don't have to work as hard because you're getting this external stabilisation from the shoe, but when you're barefoot, you have to have all of these tiny little corrections. You're using all of these foot intrinsic muscles, which can actually help to develop the arch of the foot. Also, if you have a child that's very overweight or obese, just the weight through their foot can cause them to develop a little bit more of a flat foot position.

Incidence: 7 to 22% of the general population Assessment methods:

So what are we looking for with our flat foot that would cause concern? You're looking for significant malalignment or pain that's associated with it. So when you have a low arch that typically tends to be less symptomatic than those that have a high arch, so that cavus foot is that high arch, but when you do have a painful flat foot, that's when we want to intervene. So you want to think about some things that could potentially be indicating that they would need to go see the ortho department as well. So, if you find that they have really rigid or limited subtalar motion, you want to have a tarsal coalition ruled out. So a tarsal coalition is when the bones are actually fused together rather than separate. Or some people do have an accessory navicular, so that navicular bone sticks out. So you end up weightbearing through that accessory navicular a lot, which can be really, really painful. So if there's pain with that foot deformity, it can also be because there are other things that are going on up the chain. So whenever we have an over pronation of the foot, and we have that flat foot, what we'll often see is that the leg will internally rotate. The knee moves inward, so you're getting atypical forces through the knee, atypical forces through the leg, and potentially up through the hip. From a sagittal plane, what we'll often see is that pelvis is in this anterior pelvic tilt position, and you'll have that hip and leg internal rotation and that kind of medial deviation, that pronation of the foot. So any of these things can really affect the presence of pain because again, we're changing the anatomic alignment and ground reaction forces that would go through all of the joints up the chain.

So we don't need to correct if they don't have pain, if there's no problem with their gait, or their ability to participate in activities of interest. However, you can think about just giving them shoes with an arch support when they're a little bit older so that you can just give them a little more support. It's not going to correct the flat foot, but it might just give them a little more support, a little more stability. You might see an improvement in their gait pattern, and that's totally fine. But when we do want to really pay attention and correct is when this flat foot is painful or when it's associated with another diagnosis that would typically be associated with ligamentous laxity, which tends to present with more flat feet, like down syndrome, marfan syndrome, any sort of dystrophy, or if you have a child who's going to have an atypical foot position from something like cerebral palsy. You want to correct when it's flexible. If it's a rigid foot, you correcting is probably going to cause more pain because you're trying to correct and force something into a position that it cannot obtain. And you want to try to correct when the alignment and limb biomechanics are significantly affected or the child has difficulty with ambulation. Again, because this affects so many ground reaction forces all the way up the kinetic chain, and it could lead to knee pain, hip pain, and also foot pain down the road.

Intervention:

Ways to think about intervention. If you can easily have the child go up on their tiptoes and their arch is present when they're on tiptoes, that shows that it's a flexible sort of deformity so they can regain that arch when they turn on those foot and ankle muscles. If their ankle isn't tight with dorsiflexion, if neuro screen looks good, they have no pain, they have no issues with function or tripping and they don't have any associated diagnosis like down syndrome, marfans, EDS, (Ehlers Danlos syndrome) or hypermobility, you don't need to treat them. They're fine. Maybe you can do some PT (physical therapy) where you can teach them a few exercises if the parents are really concerned. But that's really all they're going to need.

If there's an abnormal neuro screen, you want to make sure that you're going to have them see neurology. If the arch does not reform when they go up on tiptoes, it's asymmetrical, and if there's significant pain affecting ADLs, (activities of daily living) think about an ortho referral. Because if it's really rigid, we're not going to do a lot that we're going to correct in physical therapy. If they're tight when you assess ankle dorsiflexion, their ankle range of motion, they have a really difficult time getting up on their toes. They're tripping and falling a lot. They have pain in their knees and their hip and they have pain in their feet and they're under five you want to think about referring to ortho to potentially make sure that there's not something else significant going on. They may also need a physical medicine referral. Or potentially a neuro referral. And if they're six or older and they have pain in their feet and ankles, if there's any issues with the lesions on their feet or ankles, or you're really seeing that they have a lot of medial shoe wear then what you can do is you can potentially refer to podiatry or orthopaedics to make sure again that that foot is getting assessed.

This is a nice little screenshot. So this is a tool that's nice to be able to use if you're in the clinic for looking at the flat foot. So it just gives you some really nice cues. You can think about using this for any of your children who come in. So what you do is you go through. It has you check your family history. Whether there are symptoms, do they have any trauma, what's their normal activity, your systems review. Did they do any treatments already? Are they obese? A little bit or a lot? What does their gait look like when they're barefoot? With shoes on? Do they have a limp? Are there any tender areas? And if so, where? And then looking at if the foot is flexible or rigid, and some things that typically go along with a flexible foot or a rigid foot, or if that foot alignment is off. They call it skew foot here, but really that metatarsus adductus. And then you want to assess, okay, if it is a flexible foot, is it symptomatic or asymptomatic? And then it gives you a nice little spot where you can put in some measurements that you would assess throughout.

So overall, when we do an intervention for the flat foot, you want to think about minimising pain, increasing ankle flexibility if it's lacking, strengthening those weakened muscles of the foot intrinsics and potentially the ankle. Think about training proprioception for where they are in space, putting them on squishy surfaces, putting them on lots of different types of surfaces, and really doing a lot of education and reassurance with the family. If their ankle is tight, you want to stretch it. If you find that they're having a difficult time pulling their foot up. So really thinking about anterior posterior tibialis, those are huge ones for our people with flat feet. Flexor hallucis longus, those foot intrinsics, the abductor hallucis. So all of these nice foot muscles that you can strengthen to really try to help strengthen that arch. And then potentially thinking about orthotics.

Pes Cavus[edit | edit source]

Clubfoot (Talipes Equinovarus)[edit | edit source]

The incidence is one in 1000 live births. This is really easily recognised at the time of birth. It can be unilateral or bilateral. Often when you see clubfoot, that foot is smaller and shorter. There's an empty heel pad and there's also a crease that's called this transverse plantar crease that would run along the bottom side of the foot at this kind of angle.

So this just kind of breaks down the term of it. So really we're talking about the 'tali' comes from the talus or ankle, and then the 'pes' comes from the foot. So that goes together to give you your ankle and foot, and then equinovarus means that the heel is elevated and then hindfoot is turned inward. Often with this, we will also see forefoot adductus and pes cavus. Clubfoot often involves bone deformities and malposition of the soft tissue with contractures that are present.

This can happen idiopathically. We might not know why. It can be from vascular deficiencies or environmental factors like not having enough amniotic fluid for their gestational age. It could come from in-utero positioning, abnormal muscle insertions or some genetic factors are associated with clubfoot, and there is a possible association with arthrogryposis and spina bifida.

There's a couple different classification systems for severity of clubfoot. So this is just one classification system where basically what you do is you look at these different parameters and you score them. So you look at if the midfoot has a curved lateral border, if it's normal, they get zero points. If it's moderate, they get 0,5, and if it's severe, they get one. You look at how much that medial crease is present, if it's normal, moderate, or severe, and how much of the talus is covered. And then looking at the hindfoot for a posterior crease, if it's rigid, and if there's that empty heel pads. You can see higher scores are worse. It indicates more severe presentation.

And then there's also this which I really like. And so what this does is it classifies it by a one through a four, and this is giving you either a benign, moderate, severe, or very severe presentation. Here you can see the frequencies of those different presentations. So you can see that kind of these moderate and severes are the most common while the benigns and the very severes are less common. So what you do is you look at four different positions and assess how much range of motion is available and where they present at. So you're going to look at how much plantarflexion they're in. So if they can get minus 20 degrees of dorsiflexion, that's really good. So they get this one point for that. If they have between zero and negative 20 degrees so they can get to neutral or plantarflexed up to 20 degrees, they would get two points. If they're plantarflexed between 20 to 45 degrees, they would get three. And if they're plantarflexed between 45 and 90 degrees, they would get four points. From a frontal plane, what you'll do is you'll look at the heel and how varus to the heel is, so if it's able to get to that valgus to neutral position, so minus 20 to zero, that's going to get that one point. If they're in that zero to 20 range, they get two. The 20 to 45 range, they get three points. And if they're between 45 degrees and 90 degrees of hindfoot varus, they're going to get four points. You also want to look at the foot in relation to the leg and how much of that foot is coming inwards. So if it's anywhere from zero to minus 20 degrees, so pointed a little out, they get one point all the way up to, if it's between 45 and 90 degrees pointed inwards, they're going to get that four points. And then lastly, this horizontal plane of looking at the plantar aspect of the foot. And how much that forefoot is adducted inwards with that 45 to 90 degrees of forefoot adduction giving you four points. So again, the more points, the more severe the score. So this is just a really nice way to be able to assess and identify the severity of the clubfoot.

So, what do we do about clubfoot? The standard is the Ponseti method. It's been around for a long time since the 1940s. It's this really comprehensive technique for treating congenital clubfoot abnormalities. The thing is, is it's a long process and if you don't follow through with the whole process, risk of recurrence is higher.

So really what we want to think about doing is taking and applying forces to the foot that start within the first few weeks of life. And if we apply forces gradually over time, a lot of club feet can be corrected without major reconstructive surgery, but still might be associated with some minor reconstructive surgery. So this has become the most widely practised technique and method for initial treatment of infants with clubfoot. So we're going to go through the Ponseti method a little bit so that you have a good understanding of the different components.

So there's two phases, the treatment phase and the maintenance phase. The maintenance phase is the one that's really tough because a lot of families, because of just the amount of effort that it requires, aren't able to consistently keep up with it, and this is done to prevent recurrence. So a lot of times this is when we'll see they have a good correction. But they're unable to maintain it. So the treatment phase is when the deformity is actually physically corrected. Maintenance phase is a time when there's braces that are utilised to prevent recurrence. So it's really important to pay attention to details because you really want to make sure that you get all of these corrections appropriate as you go along.

So treatment, you want to begin this as early as possible. We're talking within the first week of life. Typically what happens is first, you have manipulations and casting that are done on a weekly basis. So you have a serial casting that is done, so you get a cast. A week later, the cast gets taken off and changed, and the foot gets put in a new position. So this cast is meant to hold the foot in a corrected position and allow it to reshape gradually over time. Typically you're going to need about five to six casts to fully correct the alignment of the foot and the ankle. And when that final cast goes on, the majority of infants will then still require a minor surgery compared to what it would take to surgically correct everything. And this is to gain adequate length of their Achilles tendon. It's called a percutaneous Achilles lengthening.

So in that maintenance phase, the final cast is going to remain in place for three weeks, and then the foot is going to be placed into a removable orthotic device. The orthotic needs to be worn for 23 hours per day for three months, and then during the nighttime for several years after that. So you can see why the carryover of this with families is potentially difficult. But failure to carry over and use this properly and correctly in its entirety, can result in recurrence of the clubfoot deformity. So good results have been demonstrated when people are able to maintain this protocol and they can have foot function like a typical foot.

So all of the casts are long leg casts that are applied, and they're applied from the toes all the way up to the groin, and they are going to address a lot of different corrections that are needed. So the first cast, or really address that pronation and plantarflexion of the first ray and the forefoot adduction. So, after the first cast, the foot is much straighter and that cavus position of the foot are often no longer present. The second cast is going to focus more on straightening the foot and aligning the forefoot with the heel. So for this we really want to make sure that we still keep them in plantarflexion. We're not worried about getting that dorsiflexion range of motion yet, because we're still working on the foot position. So before casting, you'll have someone that's going to manipulate the foot, determine the amount of correction that they can maintain, hold that position, they'll apply this plaster cast, and really focusing again on that forefoot abduction. So moving it out of that adducted position. The heel is often not directly manipulated. So even though that heel is really pulled inwards a lot of the time, what often happens is there's a gradual correction of the hindfoot and the midfoot. As that forefoot is corrected.

Further casting goes from four to five casts beyond that, and for this, we're really looking at, again, continuing to correct the foot position, the forefoot position. Allow that hindfoot varus to realign. And then once the hindfoot is realigned, that's when you can start to work on the dorsiflexion. If after all of the casting, their dorsiflexion is still less than 15 degrees past neutral. That's when they'll do that percutaneous Achilles tenotomy. So that percutaneous tendon release is really when that achilles tendon is still too short and the child can't fully dorsiflex through a full range of motion.

So it happens in most children. I think up to 70% of them will still require this. And this is to allow that full ankle range of motion. But it's relatively a small procedure compared to the malalignment that we see originally from a clubfoot. And then a final cast is put on. Goals of this cast are 15 degrees of dorsiflexion and 70 degrees of foot abduction. This is typically on for three weeks and more are really rarely needed unless it's some really severe cases of clubfoot. So the results are really good. So you can see here stage one up through those mid stages of casting until you get that nice neutral foot alignment and then you get that dorsiflexion. And this is kind of what their casts look like as they went through their casting.

So the maintenance and recurrence prevention is really the tough part. So after you get that final cast cut off, they're often placed in this foot abduction orthosis. And this is really to maintain foot in proper position with the forefeet really set apart and pointed upwards. And this is unfortunately used with a brace that has shoes mounted to a bar and it needs to be worn 23 hours a day for the first three months of life, and after that, sleeping for several years, around age of three or four. So you can see that when you do this perfectly, the recurrence is close to zero, but doing this perfectly is really, really hard. So when it's not worn, according to the guidelines, there is a much higher risk of recurrence.

Because the risk of recurrence can persist for several years after the casting is complete. What you want to do is as soon as you start to notice that there is a recurrence, go back, have more long leg plaster casts applied at two week intervals. So again, we're going back to the serial application of casting and that's really going to help to correct the foot deformity and any ankle tightness that has developed since then. An Achilles tendon lengthening could potentially be necessary if you aren't able to fully correct and regain that ankle range of motion. And then even more in depth as a tendon transfer where they'll take the tibialis anterior tendon and transfer it to be able to give the Achilles more length. And this can be done in older children to help maintain the correction if their ankle starts to get tight again.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA). Metatarsus Adductus. Available from: https://posna.org/physician-education/study-guide/metatarsus-adductus (accessed 29 October 2023).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Eskay, K. Paediatric Physiotherapy Programme. Paediatric Conditions of the Foot. Physioplus. 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Alonge VO. Proposing Transmalleolar Axis Bisector (TMAB) as a Geometrically Accurate Alternative to the Heel Bisector Line for the Clinical Assessment of Metatarsus Adductus. Int J Foot Ankle. 2020;4:041.