Neck Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders

Introduction

This document aims to provide information of how Dysfunctional Breathing Pattern disorders are associated with neck pain (NP). Including information on; epidemiology, etiology, presentation of symptoms and provide recent evidence of the recommended management of the symptoms.

Definition/Description See breathing pattern disorders [1] See neck pain [2]

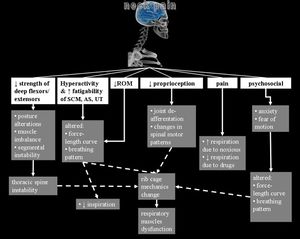

Breathing with normal respiratory mechanics has a potent role in the musculoskeletal system. Respiratory mechanics play a key role in both posture and spinal stabilization. Respiratory mechanics must be intact for both normal posture and spinal stabilization. There is a dynamic interaction between the key muscles of respiration. (Perri & Halford, 2003). Dysfunction in one can lead to a dysfunction in the other (co-dependency).

During respiration, there is a need of stabilized cervical and thoracic spine in order other muscles to act, moving the ribs up or down. In case of instability, rib cage could present mechanical alterations leading to insufficient respiratory dysfunction, influencing all muscles involved such as diaphragm, intercostals or abdominals due to adapted contraction pattern based on muscles’ force-length curve. Thus, it could be suggested that inspiration and expiration strength could be lessen in patients with neck pain.[1]

Evidence shows there is an association between neck pain and pulmonary function: A systematic review, included 68 studies, 9 were observational studies. The studies found a significant difference in maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures with chronic neck pain compared to asymptomatic patients. Respiratory volumes were lower in patients with chronic neck pain. Muscle strength and endurance, cervical range of motion, lower Pco2 were also found to be significantly correlated with reduced chest expansion and neck pain. Respiratory retraining was found to effective in improving some cervical musculoskeletal and respiratory impairment. (Kahlaee et al, 2017)[2]

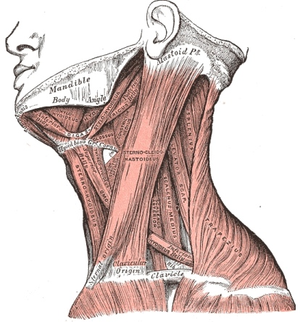

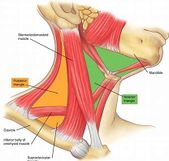

Clinically relevant Anatomy

The thoracic spine and the interconnected muscles are responsible for normal inspiration and expiration. When breathing becomes harder work or altered the body compensates by recruiting the cervical Accessory Muscles.

Scalene are invariably active during the inspiratory phase of breathing, even when the increase in lung volume is very small. The sternocleidomastoids are not active during resting breathing but they participate during strong inspiratory efforts[1].

Epidemiology/Etiology

‘A disordered breathing pattern can be the first sign that all is not well, whether it be a mechanical, physiological or psychological dysfunction’ (CliftonSmith & Rowley, 2011[3]

Incidences of Breathin Pattern Disorders

• 5-11% in general population

• 30% in asthmatics

• 83% in anxiety sufferers

• 6-10 % of patients that present to their GP may have an underlying breathing disorder[4]

Symptoms of breathing pattern disorder

• Complex, variable and multi-system

• Respiratory Breathlessness, unable to take a satisfying deep breath, tight chest, air hunger, sighing, yawning, cough & throat clearing

• Cardiac Palpitations, chest pain, tachycardia, pseudo angina, ECG changes

Symptoms

• Neurological Dizziness, faintness, numbness & tingling (facial and extremities), blurred vision, headaches, detachment from reality, muddled, lack of concentration, poor memory

• Gastrointestinal Dysphagia, heartburn, epigastric pain, reflux, burping, bloatedness, air swallowing, IBS

• Muscular Cramps, aches & pains, tremor, involuntary contractions, jaw clamping

• Psychological Anxiety, panic attacks, phobias, depression, tension

• General Weakness, exhaustion, fatigue, lethargy, Sleep disturbance, dry mouth.

Differential Diagnosis (Differentiating between BPD/NP)

(Dimitriadis et al, 2013)[5]

• Patients with CNP were found to have significant deficits in strength and endurance performance of their global and local Cervico-scapulothoracic muscles when compared to healthy patients

• Dysfunction of these muscles is believed to lead to reduced respiratory performance partly due to the common functioning of sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and scaleni on cervical movement and inspiration.

• Psychological states (e.g anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) also show significant contributions to the patients' experience of pain, respiratory and cervical dysfunction

• Clinicians are advised to consider the respiratory functioning of patients with CNP along with their psychosocial state, during their assessment to appropriately choose and administer effective treatments

Patients with CNP were found to have reduced performance of their global and local cervico-thoracic muscles. Dysfunction of these muscles is believed to lead to reduced respiratory performance partly because of the common function of sternocleidomastoid, trapezius and scalenes on cervical movement and inspiration.

(Beeckmans et al, 2016) [6]

• Systematic review (16 articles) assessing the literature pertaining to the relationship between LBP and Respiratory Disorders (RD)

• A significant correlation was observed between the presence of LBP + RD (eg. asthma, dyspnea)

• Literature indicated individuals with these particular RD reported higher rates of LBP and vice versa

• However, evidence in support of the physical mechanisms to explain this association is inconclusive

The chance of reporting LBP is greater for patients suffering from asthma or asthma-like symptoms when compared to patients without asthma. Vice versa, the occurrence of asthma is greater in patients who reported LBP ever or in the past year.

When treating LBP in patients with RD or asthma-like symptoms, adequate management of RD may also be important, together with an optimal focus LBP treatment (see page on LBP)[7]

Dysfunctional breathing may be an important focus in the rehabilitation of patients with asthma-like symptoms, in particular, stressful conditions (e.g. exercise) may lead to RD during athletic performance.

Existing evidence supports the relationship between BPD and lower back pain (Lumbar vertebra L1-L5), dysfunction of local and global muscles further up the spine that assist in respiration may contribute to NP (Cervical vertebra C1-C7).

(Blanpiedet al, 2017)[8]

An evidence-based literature review and evaluation of literature and existing medical guidelines relating to the assessment, intervention and overall management of musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders.

In addition to standard movement and strength subjective and objective examination of the neck (e.g. posture, breathing, active/passive range of motion, manual muscles tests)

While not a measure of function, pain has an effect on function and can be used as an evaluative tool

A recent piece of literature (Fillingim et al, 2015)[9] involved in this review recommended assessing 4 components of symptomatic pain:

(1) pain intensity (eg, numeric pain-rating scale)

(2) other perceptual qualities of pain (eg, asking the patient to describe the character of the pain)

(3) bodily distribution of the pain (eg, by using a body chart)

(4) temporal features of pain (eg, asking the patient how the pain fluctuates with activity and rest, and over a day, week, or month)

• Clinicians consider the use of a mechanism-based approach, such as screening tools for neuropathic pain.

• Quantitative sensory testing, including tuning forks, monofilaments, and tools for cold hyperalgesia could also play a key role in the assessment of a patient’s pain.

• Pain assessment should be combined with not only physical but psychosocial functioning examinations. [9]

(Picture)

Cranio-Cervical Flexion Test[10]

The craniocervical flexion test (CCFT) is a clinical test of the anatomical action of the deep cervical flexor muscles, the longus capitis, and colli. It has evolved over 15 years as both a clinical and research tool and was devised in response to research indicating the importance of the deep cervical flexors in support of the cervical lordosis and clinical observations of their impairment with NP.

While the test in the clinical setting provides only an indirect measure of performance, the construct validity of the CCFT has been verified in a laboratory setting by direct (EMG) measurement of deep and superficial flexor muscle activity.

This particular test can be adapted and utilized as an endurance focused exercise aimed at improving the functioning of the deep cervical flexors.

(Picture)

Breathing Pattern Disorder (BPD) Assessment

• Breath Holding – People can normally hold their breath between 25 and 30 seconds. If less than 15 seconds may mean low tolerance to carbon dioxide.

• Breathing Hi-Low Test (seated or supine) – Hands on chest and stomach, breathe normal – what moves first? What moves most? Looking for lateral expansion and upward hand pivot.

• Breathing Wave – Lay prone, breathe normal, spine should flex in a wave-like pattern towards the head. Segments that rise as a group may represent thoracic restrictions.

• Seated Lateral Expansion – Place hands on lower thorax and monitor motion while breathing. Looking for symmetrical lateral expansion.

• Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM) - Assess and quantify breathing pattern, in particular the distribution of breathing motion between the upper and lower parts of the rib cage and abdomen under various conditions. It is a manual technique that once acquired is practical, quick and inexpensive.

• Respiratory Induction Plethysmography (chest diameter/pulmonary ventilation) and Magnetometry (abdomen/chest expansion measure)

Additional questionnaires in assessment of BPD associated physical and psychological related symptoms and dysfunctions (see BPD Physiopedia page [11])

(Turk et al, 2016)[12]

Overview of outcome measures and procedures to assess a set of key psychosocial and behavioral factors that could be important in the assessment of pain.

Turk et al, 2016 advise that the presence of pain and chronic pain has a number of psychosocial and functional consequences in multiple areas of functioning (e.g. cognition, emotion, and behavior). Because chronic pain persists over time (+3 months), each of these areas will, in turn, affect the experience and reporting of pain and related symptomatic dysfunction.

Questionnaires/Inventories

• Brief Pain Inventory Short Form - (pain, physical, emotional functioning) assess the extent of the effect of pain on emotional/physical functioning

• Neck Disability Index - assess functional activities and effect of pain on dysfunction

• Quality of Wellbeing Scale - relating physical and mental symptom measures to functional aspects of life to assess the overall quality

(Picture)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A. Legrand, E. Schneider, P.A. Gevenois, A. De TroyerRespiratory effects of the scalene and sternomastoid muscles in humans J Appl Physiol, 94 (2003), pp. 1467-1472

- ↑ [null Kahlaee], A. H., Ghamkhar, L., & Arab, A. M. (2017). The Association Between Neck Pain and Pulmonary Function: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 96(3). Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Fulltext/2017/03000/The_Association_Between_Neck_Pain_and_Pulmonary.12.aspxvidence B)

- ↑ CliftonSmith, T., & Rowley, J. (2011). Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Physical Therapy Reviews, 16(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288X10Y.0000000025

- ↑ Courtney, A. C., & Courtney, M. W. (2009). A thoracic mechanism of mild traumatic brain injury due to blast pressure waves. Medical Hypotheses, 72(1), 76–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2008.08.015

- ↑ Dimitriadis, Z., Kapreli, E., Strimpakos, N. and Oldham, J. (2013). Respiratory weakness in patients with chronic neck pain. Manual Therapy, 18(3), pp.248-253.

- ↑ Beeckmans, N., Vermeersch, A., Lysens, R., Van Wambeke, P., Goossens, N., Thys, T., Brumagne, S. and Janssens, L. (2016). The presence of respiratory disorders in individuals with low back pain: A systematic review. Manual Therapy, 26, pp.77-86.

- ↑ https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain

- ↑ Blanpied, P., Gross, A., Elliott, J. and Devaney, L. (2017). Neck Pain Guidelines: Revision 2017: Using the Evidence to Guide Physical Therapist Practice. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 47(7), pp.511-512.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Fillingim, R., Loeser, J., Baron, R. and Edwards, R. (2016). Assessment of Chronic Pain: Domains, Methods, and Mechanisms. The Journal of Pain, 17(9), pp.T10-T20.

- ↑ Jull, G., O'Leary, S. and Falla, D. (2008). Clinical Assessment of the Deep Cervical Flexor Muscles: The Craniocervical Flexion Test. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 31(7), pp.525-533.

- ↑ https://www.physio-pedia.com/Breathing_Pattern_Disorders

- ↑ Turk, D., Fillingim, R., Ohrbach, R. and Patel, K. (2016). Assessment of Psychosocial and Functional Impact of Chronic Pain. The Journal of Pain, 17(9), pp.T21-T49.