Movement Control Tests For Lumbar Spine: Difference between revisions

Carin Hunter (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

In the physiotherapy community there is a general thought that the lack of movement control is related to | In the physiotherapy community, there is a general thought that the lack of movement control is related to poor adaptations. This might be due to a "lack of awareness" which could contribute to lower back pain. There is little evidence to support this, but it is considered a good assessment tool, often being used as an asterisk sign. There might be only a slight difference in movement control patterns in subjects with and without low back pain. Movement control tests should be considered when no other significant larger impairments exist. What is not known is how these can be compared to posterior chain strengthening or aerobic conditioning, both of which have been shown to improve low back pain. Further, biomedical impairments should always be graded against psychological and social “impairments”. | ||

Some patients may benefit by knowing | Some patients may benefit by knowing about their impairments and others may not. This is discretionary. It depends on how much the patient needs to know the cause of being in pain and the purpose of the interventions. Too much information may not be of much help, yet insufficient information can as well be frustrating. Good questioning will elicit patient concerns, so you would know which of the patient's needs are to be addressed. | ||

== Six Movement Control Tests == | == Six Movement Control Tests == | ||

In the study by Luomajoki<ref name=":1" />, | In the study conducted by Luomajoki<ref name=":1" />, patients did not know the tests, only a clear movement dysfunction was marked as incorrect. If the movement control was improved by instruction and correction, it was considered that it did not infer a relevant movement dysfunction. Tests<ref>Alrwaily M, Timko M, Schneider M, Stevans J, Bise C, Hariharan K, Delitto A. [https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/96/7/1057/2864925 Treatment-based classification system for low back pain: revision and update.] Physical therapy. 2016 Jul 1;96(7):1057-66.</ref> are considered positive when the subject cannot perform correctly even with cueing and demonstration<ref name=":0">Lehtola V, Luomajoki H, Leinonen V, Gibbons S, Airaksinen O. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12891-016-0986-y Sub-classification based specific movement control exercises are superior to general exercise in sub-acute low back pain when both are combined with manual therapy: A randomized controlled trial.] BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2016 Dec;17(1):1-9.</ref>. The following six movement control tests were selected by Nick Rainey for the mentoring course. They come from the following articles: | ||

* Luomajoki H, Kool J, De Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. [https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-8-90 Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine.] BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):1-1.<ref name=":1" /> | * Luomajoki H, Kool J, De Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. [https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-8-90 Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine.] BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):1-1.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

'''Test protocol:''' Flexion of the hips in upright standing without movement (flexion) of the low back.<ref name=":1" /> | '''Test protocol:''' Flexion of the hips in upright standing without movement (flexion) of the low back.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Correct''': Forward bending of the hips | '''Correct''': Forward bending of the hips 50° -70° without flexion of the low back.<ref name=":1">Luomajoki H, Kool J, De Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. [https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-8-90 Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine.] BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):1-1.</ref> | ||

'''Incorrect''': Flexion occurring in the low back prior to 50° of hip flexion.<ref name=":1" /> | '''Incorrect''': Flexion occurring in the low back prior to 50° of hip flexion.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

'''Test protocol:''' Upright sitting with corrected lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee without movement (flexion) of low back <ref name=":1" /> | '''Test protocol:''' Upright sitting with corrected lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee without movement (flexion) of low back <ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Correct''': Upright sitting with lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee to within 50° of straight without movement of | '''Correct''': Upright sitting with lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee to within 50° of straight without movement of lower back.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Incorrect''': Low back moving in flexion prior to within 50° of straight. <ref name=":1" /> | '''Incorrect''': Low back moving in flexion prior to within 50° of straight. <ref name=":1" />[[File:Sitting Knee Extension.webp|center|alt=|thumb|685x685px|Sitting Knee Extension<ref name=":1" />]] | ||

[[File:Sitting Knee Extension.webp|center|alt=|thumb|685x685px|Sitting Knee Extension<ref name=":1" />]] | |||

===== 3. Rocking Backwards: ===== | ===== 3. Rocking Backwards: ===== | ||

| Line 45: | Line 44: | ||

'''Test protocol:''' Actively in upright standing.<ref name=":1" /> | '''Test protocol:''' Actively in upright standing.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Correct''': Posterior pelvic tilt | '''Correct''': Posterior pelvic tilt is done while standing by contracting the glute max while keeping the thoracic spine in neutral<ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Incorrect''': Pelvis doesn't tilt or low back moves towards Ext./No gluteal activity/compensatory flexion in thoracic spine<ref name=":1" /> | '''Incorrect''': Pelvis doesn't tilt or low back moves towards Ext./No gluteal activity/compensatory flexion in thoracic spine<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 58: | ||

== Research Discussion == | == Research Discussion == | ||

The research by Meier et al<ref name=":2" /> evaluated whether there was a difference between people in pain and people without pain. For each positive test on the movement control tests there was an odds ratio of 1.92 more likely to have chronic low back pain.<ref name=":2" />In another study by Khodadad et al<ref name=":3">Khodadad B, Letafatkar A, Hadadnezhad M, Shojaedin S. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1941738119886854 Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment on pain and movement control in patients with low back pain.] Sports Health. 2020 May;12(3):289-95.</ref> Both the cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment improved pain and the movement control tests.<ref name=":3" />The cognitive functional treatment group class sessions involved education, exercise, and relaxation/mindfulness. Stabilization group received cues on how to properly control the spine during the following exercises which were held for 3 seconds: | The research by Meier et al<ref name=":2" /> evaluated whether there was a difference between people in pain and people without pain. For each positive test on the movement control tests, there was an odds ratio of 1.92 more likely to have chronic low back pain.<ref name=":2" />In another study by Khodadad et al<ref name=":3">Khodadad B, Letafatkar A, Hadadnezhad M, Shojaedin S. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1941738119886854 Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment on pain and movement control in patients with low back pain.] Sports Health. 2020 May;12(3):289-95.</ref> Both the cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment improved pain and the movement control tests.<ref name=":3" />The cognitive functional treatment group class sessions involved education, exercise, and relaxation/mindfulness. Stabilization group received cues on how to properly control the spine during the following exercises which were held for 3 seconds: | ||

# Planks | # Planks | ||

| Line 67: | Line 66: | ||

# Curl-up | # Curl-up | ||

In an article by Lehtola at al <ref name=":0" />, motor control exercises improved disability more than specific exercise at 3 and 12 month follow-up. The motor control exercises were more “specific” instead of general. In the article, pictures are shown of each of the specific and general exercises used but the details of the specific exercises are unclear. The goal was to train movements in different positions and re-educate how to move and control the lumbar spine in relation to the hips and thoracic spine. The general exercises are common core exercises. Both of these groups are very similar to Koumantakis’ article<ref>Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. [[Trunk muscle stabilization training plus general exercise versus general exercise only: randomized controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain.]] Physical therapy. 2005 Mar 1;85(3):209-25.</ref> in 2005. The major difference is that in this current research they screened for | In an article by Lehtola at al <ref name=":0" />, motor control exercises improved disability more than specific exercise at 3 and 12 month follow-up. The motor control exercises were more “specific” instead of general. In the article, pictures are shown of each of the specific and general exercises used but the details of the specific exercises are unclear. The goal was to train movements in different positions and re-educate on how to move and control the lumbar spine in relation to the hips and thoracic spine. The general exercises are common core exercises. Both of these groups are very similar to Koumantakis’ article<ref>Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. [[Trunk muscle stabilization training plus general exercise versus general exercise only: randomized controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain.]] Physical therapy. 2005 Mar 1;85(3):209-25.</ref> in 2005. The major difference is that in this current research they screened for subjects with psychosocial limiting factors and for those positive on at least 2 of the movement control tests which explains the difference in their results. | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 14:47, 20 January 2023

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Rishika Babburu and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

In the physiotherapy community, there is a general thought that the lack of movement control is related to poor adaptations. This might be due to a "lack of awareness" which could contribute to lower back pain. There is little evidence to support this, but it is considered a good assessment tool, often being used as an asterisk sign. There might be only a slight difference in movement control patterns in subjects with and without low back pain. Movement control tests should be considered when no other significant larger impairments exist. What is not known is how these can be compared to posterior chain strengthening or aerobic conditioning, both of which have been shown to improve low back pain. Further, biomedical impairments should always be graded against psychological and social “impairments”.

Some patients may benefit by knowing about their impairments and others may not. This is discretionary. It depends on how much the patient needs to know the cause of being in pain and the purpose of the interventions. Too much information may not be of much help, yet insufficient information can as well be frustrating. Good questioning will elicit patient concerns, so you would know which of the patient's needs are to be addressed.

Six Movement Control Tests[edit | edit source]

In the study conducted by Luomajoki[1], patients did not know the tests, only a clear movement dysfunction was marked as incorrect. If the movement control was improved by instruction and correction, it was considered that it did not infer a relevant movement dysfunction. Tests[2] are considered positive when the subject cannot perform correctly even with cueing and demonstration[3]. The following six movement control tests were selected by Nick Rainey for the mentoring course. They come from the following articles:

- Luomajoki H, Kool J, De Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):1-1.[1]

- Meier R, Emch C, Gross-Wolf C, Pfeiffer F, Meichtry A, Schmid A, Luomajoki H. Sensorimotor and body perception assessments of nonspecific chronic low back pain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021 Dec;22(1):1-0.[4]

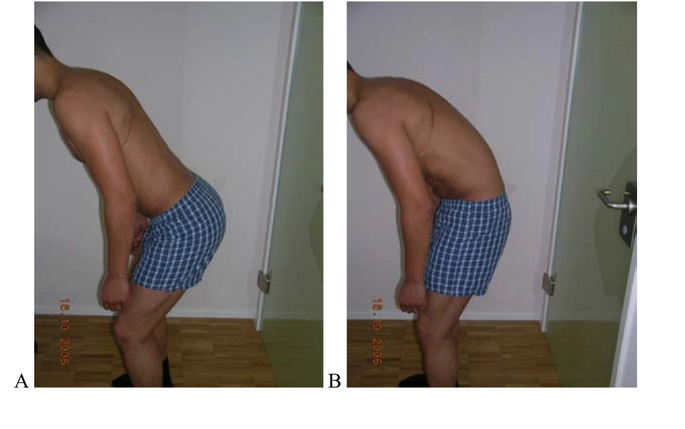

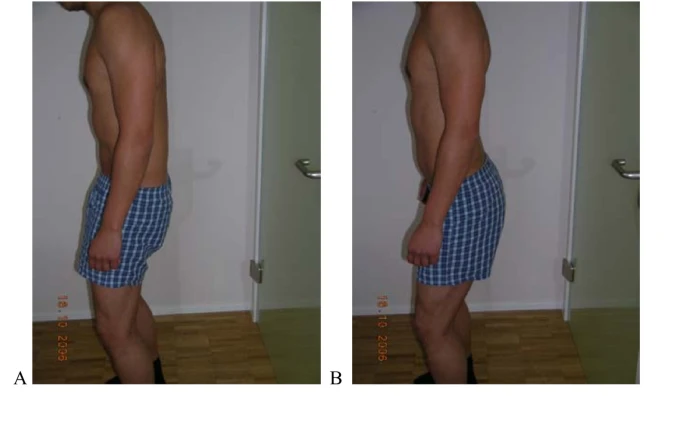

1. Waiter’s Bow:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Flexion of the hips in upright standing without movement (flexion) of the low back.[1]

Correct: Forward bending of the hips 50° -70° without flexion of the low back.[1]

Incorrect: Flexion occurring in the low back prior to 50° of hip flexion.[1]

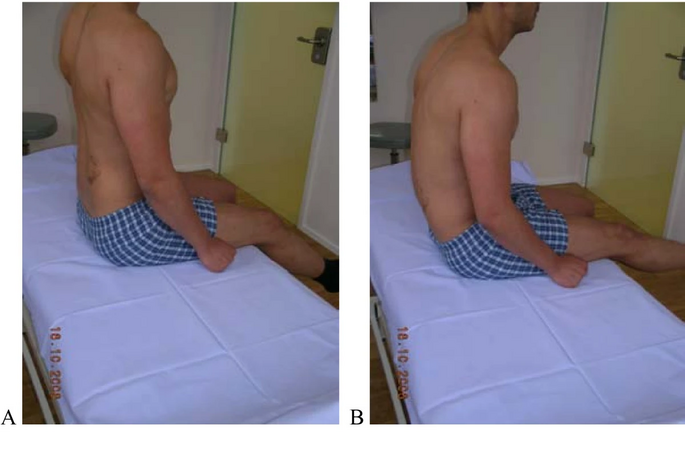

2. Sitting Knee Extension:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Upright sitting with corrected lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee without movement (flexion) of low back [1]

Correct: Upright sitting with lumbar lordosis; extension of the knee to within 50° of straight without movement of lower back.[1]

Incorrect: Low back moving in flexion prior to within 50° of straight. [1]

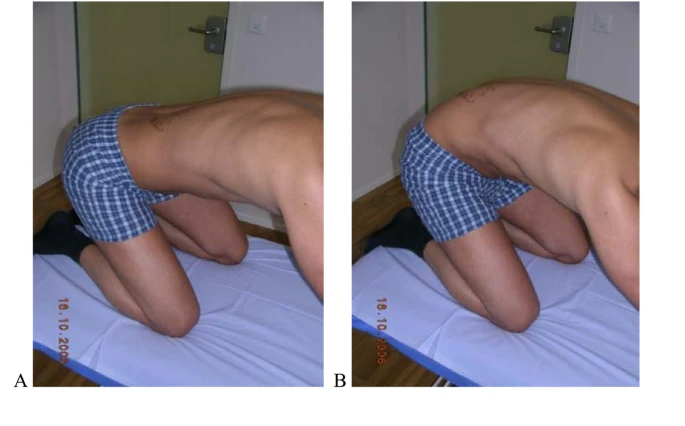

3. Rocking Backwards:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Transfer of the pelvis backwards ("rocking") in a quadruped position keeping low back in neutral.[1]

Correct: 120° of hip flexion without movement of the low back by transferring pelvis backwards.[1]

Incorrect: Hip flexion causes flexion in the lumbar spine (typically the patient not aware of this).[1]

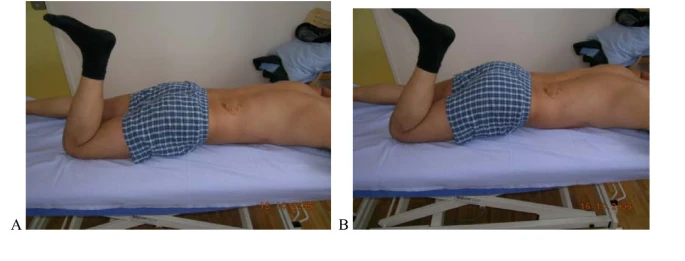

4. Prone Lying Knee Flexion:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Actively in prone

Correct: Active knee flexion at least 90° without extension movement of the low back and pelvis.[1]

Incorrect: Low back does not stay neutral, but moves into extension[1]

5. Posterior Pelvic Tilt:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Actively in upright standing.[1]

Correct: Posterior pelvic tilt is done while standing by contracting the glute max while keeping the thoracic spine in neutral[1]

Incorrect: Pelvis doesn't tilt or low back moves towards Ext./No gluteal activity/compensatory flexion in thoracic spine[1]

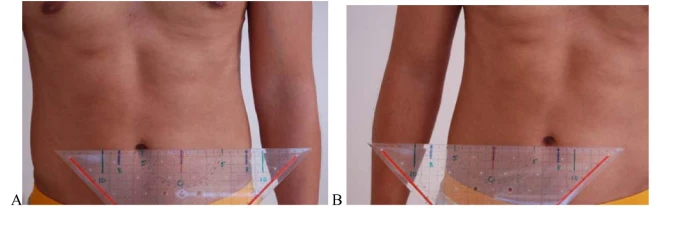

6. Single-leg Stance:[edit | edit source]

Test protocol: Patient’s feet 12cm apart. Use a 20cm ruler and hold it on a stable object with the middle of the ruler lined up with the patient's umbilicus.[1]

Correct: The patient’s umbilicus has <2cm difference side to side and <10 cm transfer on either foot.[1]

Incorrect: Lateral transfer of belly button >2cm difference side to side or > 10 cm in either direction .[1]

Research Discussion[edit | edit source]

The research by Meier et al[4] evaluated whether there was a difference between people in pain and people without pain. For each positive test on the movement control tests, there was an odds ratio of 1.92 more likely to have chronic low back pain.[4]In another study by Khodadad et al[5] Both the cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment improved pain and the movement control tests.[5]The cognitive functional treatment group class sessions involved education, exercise, and relaxation/mindfulness. Stabilization group received cues on how to properly control the spine during the following exercises which were held for 3 seconds:

- Planks

- Bridge

- Bird-dog

- Side bridge

- Curl-up

In an article by Lehtola at al [3], motor control exercises improved disability more than specific exercise at 3 and 12 month follow-up. The motor control exercises were more “specific” instead of general. In the article, pictures are shown of each of the specific and general exercises used but the details of the specific exercises are unclear. The goal was to train movements in different positions and re-educate on how to move and control the lumbar spine in relation to the hips and thoracic spine. The general exercises are common core exercises. Both of these groups are very similar to Koumantakis’ article[6] in 2005. The major difference is that in this current research they screened for subjects with psychosocial limiting factors and for those positive on at least 2 of the movement control tests which explains the difference in their results.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 Luomajoki H, Kool J, De Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Dec;8(1):1-1.

- ↑ Alrwaily M, Timko M, Schneider M, Stevans J, Bise C, Hariharan K, Delitto A. Treatment-based classification system for low back pain: revision and update. Physical therapy. 2016 Jul 1;96(7):1057-66.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lehtola V, Luomajoki H, Leinonen V, Gibbons S, Airaksinen O. Sub-classification based specific movement control exercises are superior to general exercise in sub-acute low back pain when both are combined with manual therapy: A randomized controlled trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2016 Dec;17(1):1-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Meier R, Emch C, Gross-Wolf C, Pfeiffer F, Meichtry A, Schmid A, Luomajoki H. Sensorimotor and body perception assessments of nonspecific chronic low back pain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021 Dec;22(1):1-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Khodadad B, Letafatkar A, Hadadnezhad M, Shojaedin S. Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive functional treatment and lumbar stabilization treatment on pain and movement control in patients with low back pain. Sports Health. 2020 May;12(3):289-95.

- ↑ Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. Trunk muscle stabilization training plus general exercise versus general exercise only: randomized controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain. Physical therapy. 2005 Mar 1;85(3):209-25.