Manual Therapy Techniques For The Lumbar Spine

Original Editors - Jenny Arnatt, Tabitha Eddleston, Tori Jovcic, Lizzie Wakeham

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Mobilisations[edit | edit source]

Joint mobilisation is a treatment technique which can be used to manage musculoskeletal dysfunction [1]Hertling et al (1996), by restoring the motion in the respective joint [2](Randall, 1992). The techniques are performed by physiotherapists, and fall under the category of manual therapy. Spinal mobilisation is described in terms of improving mobility in areas of the spine that are restricted [3](Korr 1977). Such restriction may be found in joints, connective tissues or muscles. By removing the restriction by mobilisation the source of pain is reduced and the patient experiences symptomatic relief. This results in gentle mobilisations being used for pain relief while more forceful, deeper mobilisations are effective for decreasing joint stiffness. [4] (Maitland 1986).

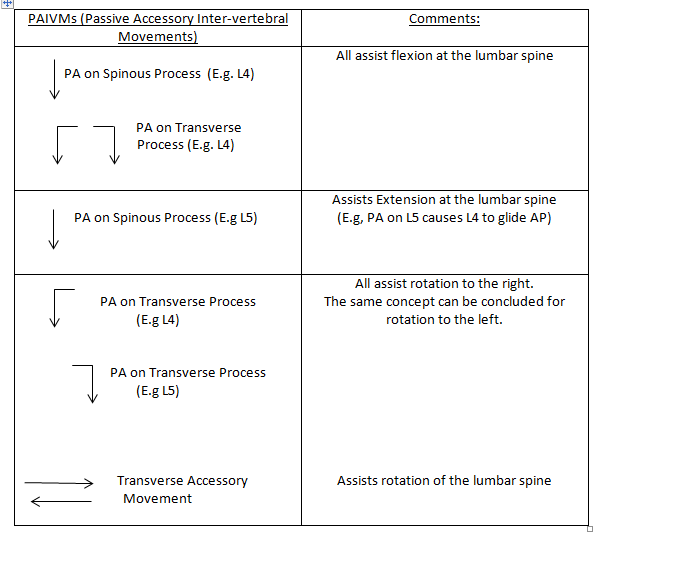

Mobilisations primarily consist of passive movements which can be classified as physiological or accessory [5](Porter, 2005). The purpose is to provide short term pain relief and to restore pain-free, functional movements by achieving full range at the joint [6](Maitland et al, 2005).

Background[edit | edit source]

Mobilisations of the Lumbar Spine

[edit | edit source]

Central Posteroanterior (PA) Mobilisation Technique[edit | edit source]

For this manual therapy technique, the patient is often positioned in prone with their arms by their side and a pillow under their abdomen for comfort [7] (Powers et al, 2009). A PA mobilization is then performed by a physiotherpist by placing their thumb or pisiform over the spinous process of a vertebrae and applying a posteroanterior force.

PAs are a commonly used manual therapy technique that has shown to be effective at reducing pain in patients with low back pain (LBP) (Shum, Tsung and Lee, 2012). So far, evidence suggests immediate pain relief following treatment, and also some evidence suggests an increased range of movement (ROM) of lumbar extention (McCollam and Benson, 1993, Shum, Tsung and Lee, 2012, and Powers et al, 2009). However, literature is still variable on the overall effects of ROM and pain[8].

Mobilisations to increase lumbar flexion[edit | edit source]

During flexion, the superior vertebral body moves relatively forward and up on the vertebral body inferiorly[9]. Therefore, to aid flexion the mobilisation needs to be applied to the vertebra above the stiff/painful vertebra to facilitate the anterior-superior translation of the facet joints.

'Central Posteroanterior (PA) mobilisation': With the patient lying in prone, the therapist stands to the side of the patient and places their pisiform/ ulnar surface of their hand over the spinous process (SP) of the selected vertebra with their wrist in full extension. The other hand is then placed on top to reinforce. The therapist’s shoulders should be directly above the SP with the elbows slightly bent. The therapist then uses their body weight to apply a PA force to the selected SP by leaning their body over their arms and performing rocking movements to provide oscillatory movements of the vertebra.

On initial assessment and treatment, if the patient has very limited movement, a pillow can be placed underneath their abdomen, or the head end of plinth can be raised to position the Lumbar spine in relative extension. Similarly, if the patient cannot tollerate pressure directly through the spinous process, the therapist can apply pressure either side of the SP with either thumb on the transverse processes.

Equally, as the patient’s pain and stiffness reduces the position of the patient can be altered to increase flexion nearer to end of range. This can be done by either lowering the foot section of the plinth or kneeling the patient on the floor by the foot of the plinth with his trunk flexed over the plinth ( approx. 20 degrees flexion) [10]

Recording[edit | edit source]

Prescription of Mobilisations[edit | edit source]

Thus far, there is no definitive evidence for the optimum duration, frequency or amplitude for mobilisation techniques. However, Most researchers have investigated subject responces' to 3 cycles of 60 second mobilisation which have shown to have positive effects [11] [12]. However, the duration and frequency should be tailored to the patient's irritability and the preference of both patient and therapist[13].

Current guidlines also suggest that non-specific LBP patients should recieve a 12 week course of manual therapy[14]

Moreover, it is generally agreed that the oscilliation depth and amplitude of movement is dependent on the patients symptoms.

If the patient's main symptom is pain then oscillation depth should remain shallow (<55%) and should be maintained within a pain free range (e.g. Grade I and II). However, if the patient's main complaint is of stiffness then the depth of oscillation can progress to end of range providing pain is tolerable (e.g. Grade III and IIII)

Maitland Scale of Mobilisations[15]:

Grade I - Small amplitude + slow oscillations in pain free zone (<25% ROM)

Grade II- Large amplitude + slow oscillations in pain free zone (<55% ROM)

Grade III- Large amplitude + slow oscillations mid to end of range

Grade IIII- Small amplitude + slow oscillations at end of range

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Hertling D., and R.M. Kessler. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams &amp; Wilkins, 1996.

- ↑ Randall et al, 1992

- ↑ Korr IM (1977): The neurobiologic mechanisms in manipulative therapy. New York, Plenum Press.

- ↑ Maitland GD (1986): Vertebral manipulation, 5th ed. Sydney, Butterworths.

- ↑ Porter, S., (2005) Dictionary of Physiotherapy. Elsevier. London.

- ↑ Maitland, G., Hengeveld. E., Banks, K. and English, K., (2005). Maitland's Vertebral Manipulation. 7th Edition. Elsevier. London

- ↑ Powers, C.M., Beneck, G.J., Kulig, K., Landel, R.F. and Fredericson, M., 2008, "Effects of a Single Session of Posterior-to-Anterior Spinal Mobilization and Press-up Exercise on Pain Response and Lumbar Spine Extension in People with Nonspecific Low Back Pain", Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association

- ↑ Rubinstein, S.M., Assendelft, T.C.M., de Boer,M.R. and van Tulder, M.W., 2012, "Spinal Manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain (Review),Cochrane,Issue.12

- ↑ Palastanga, N., Soames, R. and Palastanga, Dot.,2008, Anatomy and human movement pocketbook, London, Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Maitland, G.D., Hengeveld. E., Banks, K. and English, K.eds., 2005,Vertebral Manipulation, Edition 7, London, Butterworth Heinsmann.

- ↑ Krouwel, O., Hebron, C. and Willett, E., 2010, "An investigation into the potential hypoalgesic effects of PA mobilisations on the lumbar spine as measured by pressure pain thresholds (PPT)",Manual Therapy, Vol. 15, Pp. 7-12

- ↑ Goodsell, M., Lee, M and Latimer, J., 2000, "Short-Term Effects of Lumbar Posteroanterior Mobilization in Individuals With Low-Back Pain",Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Theraputics, Vol. 23, No. 5.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMaitland, 2005 - ↑ N.I.C.E guidelines, 2009, Low back pain: Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Manchester.

- ↑ Cenage, G., 2002, "Joint Mobilization and Manipulation", Encylopedia of Nursing &amp;amp;amp; Allied Health, Vol.3, accessed 8 January 2013 at [&amp;amp;lt;http://www.enotes.com/joint-mobilization-manipulation-reference/&amp;amp;gt;].