Lateral Ligament Injury of the Ankle

Original Editor - The Open Physio project

Top Contributors - Ilona Malkauskaite, Shaimaa Eldib, Kim Jackson, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Samuel Adedigba, Wanda van Niekerk, Nupur Smit Shah, Naomi O'Reilly and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Lateral ligament injuries are perhaps one of the most common sports-related injuries seen by physiotherapists. Usually a result of a forced plantarflexion/inversion movement , the complex of ligaments on the lateral side of the ankle is torn by varying degrees. Although the “sprained ankle” is a relatively benign injury, inadequate rehabilitation can lead to a chronically painful ankle, reduced functional ability and increased likelihood of re-injury. Care should also be taken to avoid missing the less common causes of ankle pain, namely; small fractures around the ankle and foot (e.g. Pott's fracture) and straining or rupture of the muscles around the ankle (e.g. calf, peroneii, tibialis anterior).

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Bones[edit | edit source]

The bones that make up the ankle joint include the distal tibia and fibula (the medial and lateral malleolus, respectively) and the talus.

Joints[edit | edit source]

The talocrucal (ankle) joint is a hinge joint between the inferior surface of the tibia and the superior surface of the talus. It allows the movements of Plantarflexion and Dorsiflexion. Plantarflexion is the least stable position of the ankle joint, which explains why the majority of ankle injuries occur in this position.

- The inferior tibiofibular joint is the articulation between the distal parts of the tibia and fibula. A small amount of rotation, important for walking, is present at this joint.

- The subtalar joint is an articulation between the talus and calcaneus and allows the movements of eversion and inversion. It also has an important role as a shock absorber.

Ligaments[edit | edit source]

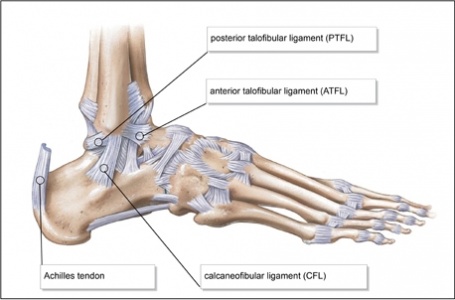

- The lateral ligament, composed of the anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneo-fibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talo-fibular ligament.

- The medial (deltoid) ligament is much stronger than the lateral ligament and is therefore injured much less frequently.

Muscles[edit | edit source]

The following muscles are involved in moving the ankle joint:

- Calf group, made up of the gastrocnemius and soleus

- Peroneii

- Tibialis anterior

Assessment of the ankle joint[edit | edit source]

The aims of the physical examination are to determine the:

- Amount of instability present by assessing the grade of the sprain

- Loss of Range of motion (ROM)

- Loss of the muscle strength

- Level of reduced Proprioception

Observation[edit | edit source]

Assessment begins with observation of the patient as they enter the room. Make a note of the gait pattern, degree of limp (if any), facial expression on weight bearing and any other signs that may provide more information about the injury.

History[edit | edit source]

Taking an accurate history is an important step in determining the nature of the injury. A Plantarflexion/Inversion injury would indicate damage to the lateral ligament, whereas a Dorsiflexion/Eversion injury would indicate damage to the medial ligament.

Previous history of injury on the same side will give clues as to whether the ankle was unstable to begin with, or that a previous injury wasn't properly rehabilitated. History of injury on the other side as well may indicate a biomechanical predisposition towards ankle injuries.

Instability and grade of sprain[edit | edit source]

Ligament sprains can be of the following grades:

Grade 1 - mild, painful, minimal tearing of the ligament fibres Grade 2 - moderate, painful, significant tearing of the ligament fibres Grade 3 - severe, sometimes not painful, complete rupture of the fibres

Range of motion (ROM)[edit | edit source]

ROM of the ankle needs to be assessed actively and passively. The movements to be assessed are:

- Plantarflexion and Dorsiflexion

- Inversion and Eversion

Strength[edit | edit source]

Resisted eversion should be assessed...

Palpation[edit | edit source]

An important aspect of the initial examination is to determine the exact site of the lateral ligament sprain, whether it's the ATFL, CFL or PTFL (usually damaged in that order). Palpating the lateral aspect of the ankle over the course of the various aspects of the ligament complex will provide detailed information on the exact location of the tear. Begin palpating gently as this can potentially be acutely painful for the patient.

Special tests[edit | edit source]

These include:

- Anterior draw

- Talar tilt

- Proprioception

- An anterior draw is done to test the integrity of the ATFL and CFL. With the ankle in plantarflexion, the heel is grasped with the tibia stabilised and drawn anteriorly.

- Talar tilt is done to assess the integrity of the ATFL and CFL laterally and the deltoid ligament medially. Again the heel is grasped, the tibia stabilised and the talus and calcaneus are moved laterally and medially.

- Proprioception can be assessed in any number of increasingly difficult ways, beginning with a simple single leg stance. The patient can do it on the normal side first, to allow the therapist to get an idea of what the normal is and then attempt on the injured side.

This test can be progressed by asking the patient to reach outside their base of support (BOS), rotating their neck or by closing their eyes. Moving onto a wobble board or any other unstable surface will allow the therapist to assess the patients ability to respond to a changing surface.

Functional movements[edit | edit source]

Functional movements such as lunges and hopping should be included in the assessment.

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A differential diagnosis must be carried out to exclude the possibility of the following, less common injuries:

- Ankle fracture (medial/lateral malleolus, distal tibia/fibular)

- Damage to the medial ligament

- Dislocated ankle

- Other soft tissue damage (peroneal tendons, muscle strain)

The Ottawa rules provide useful guidance on determining the presence of a fracture. If a patient is unable to weightbear immediately following the injury, an X-ray is indicated because of the risk of a clinically significant ankle fracture. Failure to use the Ottawa rules to assess for ankle fracture may be significant in any legal proceedings should they occur.

Even though injuries to the lateral ligament are by far more common, be aware that there may be other injuries associated with the lateral ligament injury. Missing an associated injury may hamper a return to pre-injury level of functional activity and lead to the so-called “problem ankle”.

Treatment and rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Reduce pain and swelling[edit | edit source]

- Initial management (i.e. within the first 48-72 hours) of an acute lateral ligament injury is to reduce pain and swelling by following the RICE regimen; Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation.

- If WB is too painful, the patient can be given elbow crutches and be non-weight bearing (NWB) for 24 hours. However, it's important that at least partial weight bearing (PWB) is initiated relatively soon, together with a normal heel-toe gait pattern, as this will help to reduce pain and swelling.

- Gentle soft tissue Massage (STM) can be performed to assist with the removal of oedema and gentle stretches, as long as this is pain free.

Restore ROM[edit | edit source]

As soon as pain allows, the patient should begin pain free active range of movement (ROM) exercises.

Restore strength[edit | edit source]

Eversion is especially important.

Restore proprioception[edit | edit source]

Proprioception training should begin as soon as pain allows during the rehabilitation programme.

Return to functional activity[edit | edit source]

Patients should be assessed for the ability to do the following activities pain free:

- Twisting

- Jumping

- Hopping on one leg

- Running

- Figure of 8 running

Before returning to full functional activity the patient should have full range of pain free movement in the ankle, normal strength and normal proprioception. If returning to sports, the athlete should be encouraged to wear an ankle brace or to tape the ankle for a further 6 months to provide external support. Types of taping include a heel lock and figure of 6.

Grade 3 sprains[edit | edit source]

While in the past surgery was advocated for grade 3 sprains, it's now considered that an initial 6 week conservative programme should only be followed by surgery should pain not be relieved. A recent review of the literature in the Cochrane database found little to recommend surgery over conservative management.

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.