Inactivity and Low Back Pain

Introduction[edit | edit source]

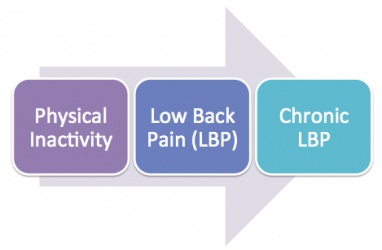

The aim of this page is to investigate the relationship of how physical inactivity can cause low back pain (LBP). Additionally we will review current literatures for and against the link of inactivity and low back pain. It ultimately aims to provide an up-to date evidence overview to health professionals and the public to help them to understand the link between.

Definitions[edit | edit source]

Chronic non-specific low back pain[edit | edit source]

According to Nice guideline 2009, the lower back can be defined as the area between the 12th ribs and the buttock creases.[1] “Non-specific low back pain is defined as low back pain not attributable to a recognisable, known specific pathology (eg, infection, tumour, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome).”[2] Low back pain is a very common condition, but when the symptoms do not resolve after normal expected tissue healing time the condition will become chronic. [3] Low back pain that lasts for longer than 7-12 weeks can be defined as chronic. Sometimes frequently recurring back pain is defined as chronic as the condition intermittently affects one for a prolonged period. [4]

Physical activity and Inactivity[edit | edit source]

“Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.”[5] Physical activity includes activity of daily living, for example, walking, housework, gardening, and work-related activity.[6] When an individual who does not meet the recommended level of physical activity will be classified as physically inactive.

The NICE guideline 2013 recommendations (UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity recommendations) for physical activity state that:

• All adults aged 19 years and over should aim to be active daily.

• Over a week, this should add up to at least 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate intensity1 physical activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more.

• Alternatively, comparable benefits can be achieved through 75 minutes of vigorous intensity2 activity spread across the week or combinations of moderate and vigorous intensity activity.

• All adults should also undertake physical activity to improve muscle strength on at least 2 days a week.

• They should minimise the amount of time spent being sedentary (sitting) for extended periods.

• Older adults (65 years and over) who are at risk of falls should incorporate physical activity to improve balance and coordination on at least 2 days a week.

• Individual physical and mental capabilities should be considered when interpreting the guidelines, but the key issue is that some activity is better than no activity.[7]

The World Health Organisation has classified physical inactivity into two levels. Level 1 exposure (inactive) means the individual does very little or no physical activity at home, work, for transport or in their private time. Level 2 exposure (insufficiently active) describe individual that does physical activity less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 60 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity in all activity of daily living.[8]

The current levels of physical inactivity are partly due to insufficient participation in physical activity during leisure time and an increase in sedentary behaviour during occupational and domestic activities [WHO: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/]

Sedentary behaviour[edit | edit source]

National guidelines classify people as sedentary when the individual does less than 30 minutes of moderate activity on all or most days of the week.[9] Sedentary behaviour describes activities that do not increase energy expenditure significantly above the resting level, it includes activities such as sleeping, lying, watching television and other types of screen-based entertainment. However, light physical activity is often being mistaken as sedentary behaviour, activities like slow walking, sitting, writing and cooking actually requires energy expenditure above the resting level.[10]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Low back pain [edit | edit source]

• One-third on the United Kingdom adult population is affected by low back pain each year.[11]

• 20% (1 in 15 of the population) of people will consult a GP about their low back pain.[12]

• In Europe, the lifetime prevalence of low back pain can be as high as 84%.[13]

• After the first experience of low back pain, 44-78% people suffer relapse of pain again.[14]

• 26-37% people will have relapses of work absence after an initial episode of low back pain.[15]

• Evidence showed that the prevalence of chronic non-specific low back pain is around 23%, and 11-12% of the population are disabled by the condition.[16]

• 85% of cases are classified as non-specific low back pain as a diagnosis cannot be made by radiological methods.[17]

Physical inactivity [edit | edit source]

• Around the world, a one in five adult is considered physically inactive.[18]

• In wealthier and urban countries, women and elderly people, physical inactivity was found to be more prevalent.[19]

• Female’s physical inactivity was higher (21.4%) than men’s (18.9%).[20]

• Approximately 60% of male adult, 72% of female adult, 68% of boys and 76% of girls aged 2-15 do not meet the UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity recommendations. (See above)[21]

• Physical inactivity has been reported as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality (6% of deaths worldwide).[22]

• Around 3.2 million deaths each year are related to insufficient physical activity.[23]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures for physical activity[edit | edit source]

The outcome indicator should be chosen according to how well it measures the objectives of the study. Other important factors in choosing an outcome measure are the level of data required, the characteristics of the individual, group or population, time frame of interest and the available time and resources. [24]

Physical activity can be classified as a combination of frequency, intensity and duration. Any type of activity can be different in terms of the three different aforementioned elements, in other words, different in the volume of physical activity. A better understanding of what element or activity that the study is focused on, the easier to determine what to use as an outcome measure.

Measurement of physical activity can be challenging. The outcome measures for physical activity are generally grouped into two groups - objective measure (e.g. accelerometers) and subjective measure (e.g. questionnaires). And each has a different degree of validity, reliability, feasibility and practicality. However, there is no ‘gold standard’ for assessing physical activity in public health settings.

Validity: the extent to which an instrument genuinely records what it is intended to measure.

Reliability: how consistently an instrument or tool will measure something on two or more separate occasions.

Options for measuring physical activity suggested in Standard Evaluation Framework for physical activity interventions, published by the National Obesity Observatory.

1. A measure of specific type of physical activity

2. Measure of total physical activity

3. Proportion achieving recommended physical activity levels

(for more detail of each option, you can visit this link: http://www.noo.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_16722_SEF_PA.pdf)

A table of the outcome measures for physical activity :

| Objective Measures | Subjective Measures |

|

|

|

Self-report approaches is the most frequently used method for measuring physical activity in a public setting due to its cost effectiveness compare to other outcome measures. However, their reliance on recalling activity can be problematic, especially for children and young people. Self report of physical activity is subject to a number of types of bias, such as recall bias, lack of compliance and ‘social desirability’ bias.

Shortlist of selected questionnaires for physical activity by NOO reviews of measurement of diet and physical activity

| Physical activity: children and young people | Physical activity: adults |

|

Children/Adolescents (PAQC/PAQ-A) 2.Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance Survey (YRBSS) |

1. Stanford 7-day recall (7-DR) 2. International Physical Activity Questionnaire Long version (IPAQ-Long) 3. New Zealand Physical Activity Questionnaire (Short Form) (NZPAQ-Short) |

(For more detail of individual questionnaire, visit the link: http://www.noo.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_10414_Assessment%20Tools%20160311%20FINAL%20MG.pdf)

A recent systematic review done by Falck et al. 2015, the aim of the review is to evaluate the measurement tools used in interventions to increase physical activity among older adults, including both objective and subjective measures. 44 studies are included, 32 of them used self-report measure and 9 used objective measures and only 3 used both measures. Among all the measures only 57% of them had population specific reliability and 66% had population- specific validity. A majority of the studies use self- report measures, even though many have little evidence of validity and reliability. The researchers of the systematic review suggested that future researchers should use valid and reliable measures of physical activity with well-established evidence of psychometric properties, for instance hip-accelerometers and the community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors Physical Activity Questionnaire for older adults. I strongly agree with the idea, as the advance in modern technology, the access to the technology for measuring physical activity, such as accelerometers and pedometers, is easier than before, future researchers should take the chance and improve their studies quality by using a better measurement tool. 11 On the other hand, it is important to note that most of the questionnaires were not developed for use in individual or group interventions, but population surveillance. In some cases, the tools may not be sensitive enough to measure the outcome. Furthermore, none of the tools can adequately detect change in physical activity over time, but a snapshot of a particular period of time. 1

Outcome Measure for Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

- numerical rating scale (NRS)

- Roland–Morris disability questionnaire (RMDQ)

- Oswestry disability index (ODI)

- pain self-efficacy questionnaire (PSEQ)

- the patient-specific functional scale (PSFS)

Other Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

BMI, physiological measures and quality of life are usually used to be a secondary outcome measure for physical activity. Such outcomes should only be measures if they are relevant to the aims of the study or researcher’s interest.

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

Deconditioning[edit | edit source]

Body composition and bone strength[edit | edit source]

As a reduced physical activity level, eventually leads to weight gain and a change in body composition, patients with LBP are reported to have a higher body fat percentage compared to age- and gender- matched individuals. In addition, bone health is also likely to be affected in an inactive population. According to Wolff’s Law, if the loading on a bone decreases, the bone will become less dense and weaker due to the lack of the stimulus required for continued remodelling and increased resorption from osteoclasts. Conversely, if loading on a particular bone increases, the bone will remodel (increased osteoblast activity) itself over time to become stronger to resist that sort of loading. However, current evidence still lacks strong high quality to confirm the inverse relationship between back pain and bone health.

Verbunt, J.A., Seelen, H.A., Vlaeyen, J.W., Bousema, E.J., van der Heijden, G.J., Heuts, P.H. and Knottnerus, J.A., 2005. Pain-related factors contributing to muscle inhibition in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental investigation based on superimposed electrical stimulation. The Clinical journal of pain, 21(3), pp.232-240.

Kriska, A.M., Saremi, A., Hanson, R.L., Bennett, P.H., Kobes, S., Williams, D.E. and Knowler, W.C., 2003. Physical activity, obesity, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in a high-risk population. American Journal of Epidemiology, 158(7), pp.669-675.

Briggs, A.M., Straker, L.M. and Wark, J.D., 2009. Bone health and back pain: What do we know and where should we go?. Osteoporosis International, 20(2), pp.209-219.

Wolff, J., 2012. The law of bone remodelling. Springer Science & Business Media.

Briggs, A.M., Straker, L.M. and Wark, J.D., 2009. Bone health and back pain: What do we know and where should we go?. Osteoporosis International, 20(2), pp.209-219.

Factors that affect adults’ participation in physical activity[edit | edit source]

Occupation[edit | edit source]

Environment[edit | edit source]

Race/ethnicity, social class and etc.[edit | edit source]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Evidence for[edit | edit source]

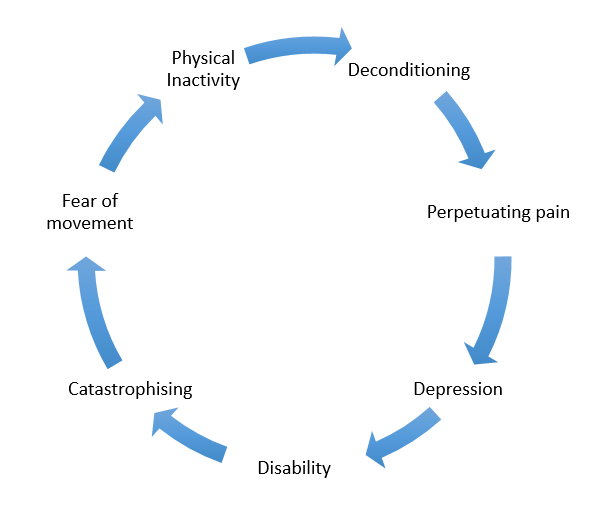

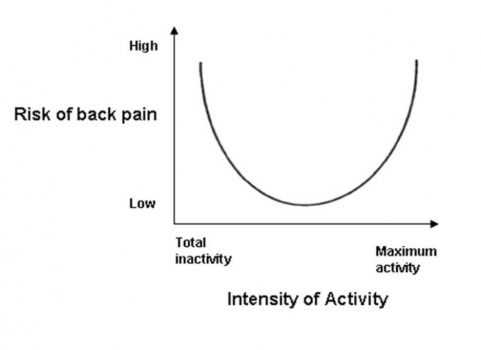

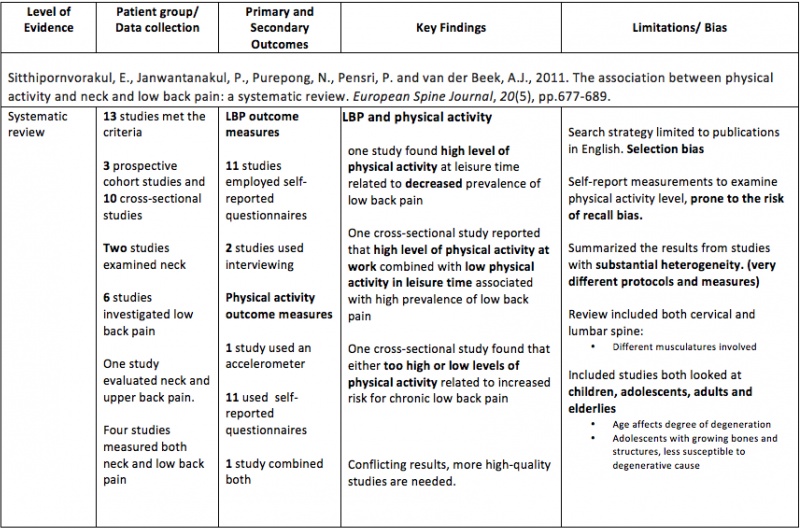

A Dutch cross-sectional study from 2009 investigated the U-shaped relationship between physical activity and low back pain. The study concluded that both extremes of physical activity- excess activity or insufficient activity associated with a high risk of LBP (fig x). An increased prevalence in LBP was also found in inactive participants with sedentary behavior. In addition to that, there is a potential gender-related risk for LBP in inactivity because the result is more significant in women compared to men.

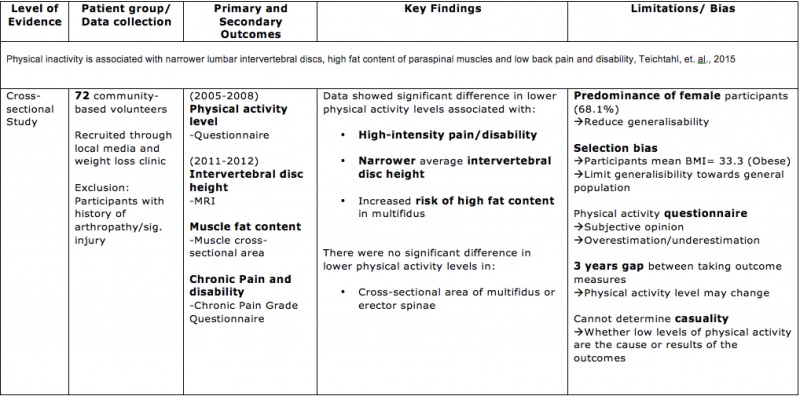

Another cross-sectional study from 2015 explored the associations between physical inactivity and intervertebral disc height, spinal muscles fat content and low back pain and disability. Results concluded that participants with lower activity levels had higher BMI, narrower intervertebral disc height, higher fat content of multifidus, increased risk of high-intensity pain/disability ratio after adjustment for age, gender and BMI.

Evidence against[edit | edit source]

A systematic review written in 2011 reviewed 7 studies to look at whether patients with chronic low back pain have an altered level and/or pattern of physical activity compared to healthy individuals. The gathered data revealed no significant difference in the overall activity level of adults (18-65 y/o) or adolescents (<18y/o) with chronic low back pain, however there is evidence that older adults (>65 y/o) with chronic low back pain are less active than controls. They concluded that there is no conclusive evidence that patients with chronic low back pain are less active than healthy individuals and there is a lack of number of studies in this area.

Limitations[edit | edit source]

cross-sectional studies

-physical activity is continuous and intensity could change.

--> longitudinal design would be more reliable

-difficult to identify casualty

-->whether physical inactivity is causing low back pain or vice versa

-other factors which could influence low back pain

--> such as BMI and age

pain is a complex outcome measure: use questionnaires, could lead to overestimation or underestimation.

Clinical Bottom Lines[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2009) Low back pain in adults: early management. [Online]. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88/resources/low-back-pain-in-adults-early-management-975695607493. [Accessed: 9 January 2016].

- Balagué, F., Mannion, A. F., Pellisé, F., & Cedraschi, C. (2012). Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet, 379(9814), 482-491.

- O’Sullivan, P. (2005). Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Manual therapy, 10(4), 242-255.

- Andersson, G. B. (1999). Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. The lancet, 354(9178), 581-585.

- Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health reports, 100(2), 126.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2013) Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. [Online]. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44/resources/physical-activity-brief-advice-for-adults-in-primary-care-1996357939909. [Accessed: 9 January 2016].

- World Health Organization. (2009). Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. World Health Organization.

- Biddle, S. J., Gorely, T., Marshall, S. J., Murdey, I., & Cameron, N. (2004). Physical activity and sedentary behaviours in youth: issues and controversies. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 124(1), 29-33.

- Pate, R. R., O'Neill, J. R., & Lobelo, F. (2008). The evolving definition of" sedentary". Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 36(4), 173-178.

- Airaksinen, O., Brox, J. I., Cedraschi, C. O., Hildebrandt, J., Klaber-Moffett, J., Kovacs, F., ... & Zanoli, G. (2006). Chapter 4 European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. European spine journal,15, s192-s300.

- Dumith, S. C., Hallal, P. C., Reis, R. S., & Kohl, H. W. (2011). Worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and its association with human development index in 76 countries. Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 24-28.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2012) Physical activity: Local government briefing. [Online]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/lgb3/resources/physical-activity-1681146084805. [Accessed: 9 January 2016].

- World Health Organisation. Physical Activity. [online]. Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/ [Accessed 9 January 2016].

- World Health Organisation. Physical Inactivity: A Global Public Health Problem. [online]. Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/ [Accessed 9 January 2016].

- Outcome measuress' references

- Cavill N, Roberts K, Rutter H. (2012) Standard Evaluation Framework for Physical Activity Interventions. London: National Obesity Observatory.

- Richardson D, Cavill N, Ells L, Roberts K. (2011) Measuring Diet and Physical Activity in Weight Management Interventions: a Briefing Paper. Oxford National Obesity Observatory

- Richardson D, Cavill N, Ells L, Roberts K. (2011) Supplement: Measuring Diet and Physical Activity in Weight Management Interventions. Oxford National Obesity Observatory.

- Hillsdon M (2009) Tools to measure physical activity in local weight management interventions: a rapid review. Oxford: National Obesity Observatory.

- Biddle SJH, Gorely T, Pearson N, Bull FC (2011) An assessment of self-reported physical activity instruments in young people for population surveillance: Project ALPHA. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2011, 8:1.

- Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M (2008) A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. Nov 6;5:56.

- Block G, Hartman AM.(1989) Issues in reproducibility and validity of dietary studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition 1989;50(5 Suppl):1133-8; discussion 231-5

- Gibson RS.(2005) Principles of nutritional assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dugdill L, Stratton G (2007) Evaluating Sport and Physical Activity Interventions. Salford: University of Salford/Sport England.

- Medical Research Council. Diet and physical activity measurement toolkit (http://toolkit.s24.net/index.html)

- Falck, R. S., McDonald, S. M., Beets, M. W., Brazendale, K., & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2015). Measurement of physical activity in older adult interventions: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2014.

- Elaine F. Maughan and Jeremy S. Lewis (2010) Outcome measures in chronic low back pain, Eur Spine J. 2010 Sep; 19(9): 1484–1494, Published online 2010 Apr 17. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1353-6