Inactivity and Low Back Pain

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The aim of this page is to investigate the relationship between inactivity and chronic non-specific Low back pain. Additionally we will review current literatures for and against the link of inactivity and low back pain. It also aims to provide evidence and an overview to health professionals and the public to help them to understand the link between them.

Definitions[edit | edit source]

Chronic non-specific low back pain[edit | edit source]

According to Nice guideline 2009, the lower back can be defined as the area between the 12th ribs and the buttock creases. “Non-specific low back pain is defined as low back pain not attributable to a recognisable, known specific pathology (eg, infection, tumour, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome).”[1] Low back pain is a very common condition, but when the symptoms do not resolve after normal expected tissue healing time the condition will become chronic. [2] Low back pain that lasts for longer than 7-12 weeks can be defined as chronic. Sometimes frequently recurring back pain is defined as chronic as the condition intermittently affects one for a prolonged period. [4]

Physical activity and Inactivity[edit | edit source]

“Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.” [8] Physical activity includes activity of daily living, for example, walking, housework, gardening, and work-related activity. [7] When an individual who does not meet the recommended level of physical activity will be classified as physically inactive.

The NICE guideline 2013 recommendations (UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity recommendations) for physical activity state that:

• All adults aged 19 years and over should aim to be active daily.

• Over a week, this should add up to at least 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate intensity1 physical activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more.

• Alternatively, comparable benefits can be achieved through 75 minutes of vigorous intensity2 activity spread across the week or combinations of moderate and vigorous intensity activity.

• All adults should also undertake physical activity to improve muscle strength on at least 2 days a week.

• They should minimise the amount of time spent being sedentary (sitting) for extended periods.

• Older adults (65 years and over) who are at risk of falls should incorporate physical activity to improve balance and coordination on at least 2 days a week.

• Individual physical and mental capabilities should be considered when interpreting the guidelines, but the key issue is that some activity is better than no activity. [7]

The World Health Organisation has classified physical inactivity into two levels. Level 1 exposure (inactive) means the individual does very little or no physical activity at home, work, for transport or in their private time. Level 2 exposure (insufficiently active) describe individual that does physical activity less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 60 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity in all activity of daily living. [6]

Sedentary behaviour[edit | edit source]

National guidelines classify people as sedentary when the individual does less than 30 minutes of moderate activity on all or most days of the week. [11] Sedentary behaviour describes activities that do not increase energy expenditure significantly above the resting level, it includes activities such as sleeping, lying, watching television and other types of screen-based entertainment. However, light physical activity is often being mistaken as sedentary behaviour, activities like slow walking, sitting, writing and cooking actually requires energy expenditure above the resting level. [10]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Low back pain [edit | edit source]

• One-third on the United Kingdom adult population is affected by low back pain each year.

• 20% (1 in 15 of the population) of people will consult a GP about their low back pain. [3]

• In Europe, the lifetime prevalence of low back pain can be as high as 84%.

• After the first experience of low back pain, 44-78% people suffer relapse of pain again.

• 26-37% people will have relapses of work absence after an initial episode of low back pain.

• Scientific evidence is limited on the prevalence of chronic non-specific low back pain. Best evidence showed that the prevalence is around 23%, and 11-12% of the population are disabled by the condition. [5]

• 85% of cases are classified as non-specific low back pain as a diagnosis cannot be made by radiological methods. [2]

Physical inactivity [edit | edit source]

• Around the world, a one in five adult is considered physically inactive. [9]

• In wealthier and urban countries, women and elderly people, physical inactivity was found to be more prevalent. [9]

• Female’s physical inactivity was higher (21.4%) than men’s (18.9%). [9]

• Approximately 60% of male adult, 72% of female adult, 68% of boys and 76% of girls aged 2-15 do not meet the UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity recommendations. (See above) [13]

• Physical inactivity has been reported as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality (6% of deaths worldwide).

• Around 3.2 million deaths each year are related to insufficient physical activity.

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

Occupational inactivity[edit | edit source]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Evidence for[edit | edit source]

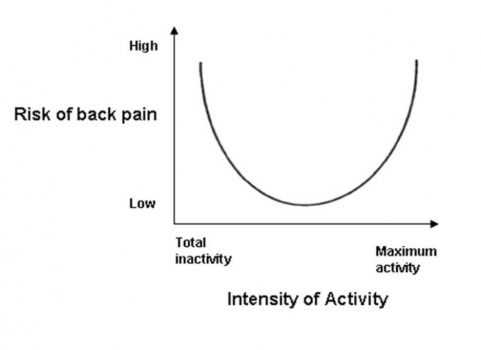

A Dutch cross-sectional study from 2009 investigated the U-shaped relationship between physical activity and low back pain. The study concluded that both extremes of physical activity- excess activity or insufficient activity associated with a high risk of LBP (fig x). An increased prevalence in LBP was also found in inactive participants with sedentary behavior. In addition to that, there is a potential gender-related risk for LBP in inactivity because the result is more significant in women compared to men.

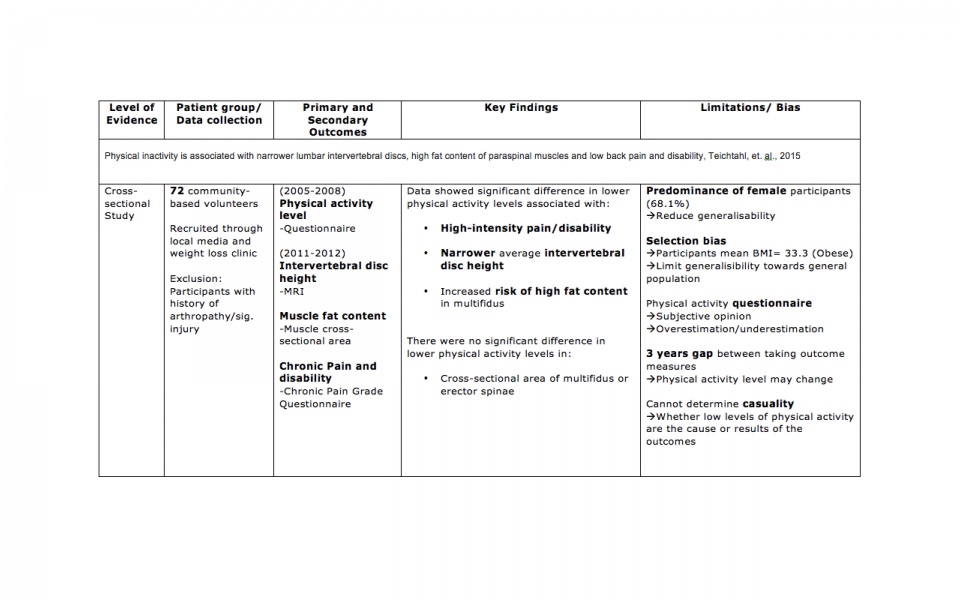

Another cross-sectional study from 2015 explored the associations between physical inactivity and intervertebral disc height, spinal muscles fat content and low back pain and disability. Results concluded that participants with lower activity levels had higher BMI, narrower intervertebral disc height, higher fat content of multifidus, increased risk of high-intensity pain/disability ratio after adjustment for age, gender and BMI.