Hip Labral Tears

Original Editor - Alisha Lopez

Lead Editors - Chris Slininger, Kristen Tsuei, Jenny Nordin, Thomas F Lawlor, Alisha Lopez

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases Searched: PTJ, Pubmed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library

Keywords Searched: hip labral tears, acetabular labrum, acetabular labral tears, hip labral lesions & examinations

Search Timeline: July 1 2011 - July 15 2011

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

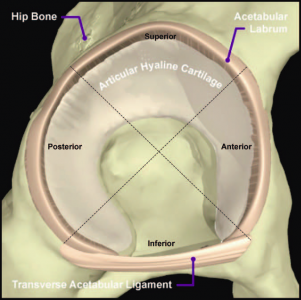

The hip labrum is a structure made of dense connective tissue and fibrocartilage that outlines the

acetabular socket. This continuous structure composed of Type 1 collagen attaches to the bony rim of the acetabulum. The labrum is wider and thinner in the anterior region of the acetabulum and thicker in the posterior region. [1][2]

As for the blood supply, it is thought that the majority of the labrum is avascular with only the

outer third being supplied by the obturator, superior gluteal, and inferior gluteal arteries. There is

controversy as to whether there is a potential for healing with the limited blood supply. The superior and inferior portions are believed to be innervated and contain free nerve endings and nerve sensory end organs (giving the senses of pain, pressure, and deep sensation). [1][2]

The labrum functions as a shock absorber, joint lubricator, and pressure distributor. It resists

lateral and vertical motion within the acetabulum along with aiding in stability by deepening the joint by 21%. The labrum also increases the surface area of the joint by 28%. This allows for a wider area of force distribution and is accomplished by creating a sealing mechanism to keep the synovial fluid within the articular cartilage. [1]

Labral tears can be classified by their location (anterior, posterior, or superior/lateral),

morphology (radial flap, radial fibrillated, longitudinal peripheral, and unstable), or etiology.[1] It is generally accepted that most labral tears occur in the anterior, anterior-superior, and superior regions of this acetabulum.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

With the advent of arthroscopic surgery as an accurate means of diagnosis (magnetic resonance arthrography), hip labral injuries have become of growing interest to the medical profession. Direct trauma, including motor vehicle accidents and slipping or falling with or without hip dislocation, are known causes of acetabular labral tears. [2] Additionally, childhood problems such as Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, congenital hip dysplasia, and slipped femoral capital epiphysis have been correlated to labral tears [3]. While most tears occur in the anteriosuperior quadrant, a higher than normal incidence of posterosuperior tears appear in the Asian population due to a higher tendency toward hyperflexion or squatting motions.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

According to a systematic review by Leiboid et al, hip labral tears can occur between 8 to 72 years of age and on average during the fourth decade of life. Labral tears may also occur more in women. 22-55% of patients that present with symptoms of hip or groin pain are found to have an acetabulular labral tear [1]. Up to 74.1% of hip labral tears cannot be attributed to a specific event or cause [1]. In patients who identified a specific mechanism of injury, hyperabduction, twisting, falling, or direct blow from a MVA were common mechanisms of injury [4]. Women, runners, professional athletes, participants in sports that require frequent external rotation and/or hyperextension, and those attending the gym 3 times a week all have an increased risk of developing a hip labral tear [4].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Given the etiology of this condition it is very important to obtain a good history, paying close attention to childhood problems such as Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, congenital hip dysplasia, slipped femoral capital epiphysis and trauma.

Schmerl and colleagues provide a thorough list for differential diagnosis of labral injury causing hip pain:

- Contusion (especially over bony prominences)

- Strains Athletic pubalgia

- Osteitis pubis

- Inflammatory arthridites

- Piriformis syndrome

- Snapping hip syndrome Bursitis (trochanteric, ischiogluteal, iliopsoas)

- Osteoarthritis of femoral head

- Avascular necrosis of femoral head

- Septic arthritis

- Fracture or dislocation

- Tumors (malignant and benign)

- Hernia (inguinal or femoral)

- Slipped femoral capital epiphysis

- Legg-Calve-Perthes disease

- Referred pain from lumbosacral structures and the sacroiliac joint

Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is the diagnostic of choice for hip labral tears. Magnetic resonance imaging (without arthrography) and computed tomography (CT) have been shown to be unreliable diagnostic tests. [1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Pain: VAS

Muscle strength: measured by MMT and dynamometer

Disability: Lequesne Hip Score

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Due to difficulties in identifying specific mechanisms of injury for hip labral tears, generalizing typical signs and symptoms proves to be a rather challenging task. Ninety percent of patients with a hip labral tear have complaints of anterior hip and/or groin pain. [1][2] Less common areas of pain include anterior thigh pain, lateral thigh pain, buttock pain, and radiating knee pain. [4][1] Pain patterns and additional symptoms reported in studies include insidious onset of pain, pain that worsens with activity, night pain, clicking, catching, or locking of the hip during movement [2][1]. Functional limitations may include prolonged sitting, walking, climbing stairs, running, and twisting/pivoting [2][4][1].

According to a 2008 study by Martin et al, symptoms of groin pain, catching, pinching pain with sitting, FABERs test, flexion-internal rotation, adduction impingement test, and trochanteric tenderness were found to have low sensitivities (.6-.78) and low specificities (.10-.56) in identifying patients with intra-articular pain.

Examination[edit | edit source]

After obtaining a thorough history, a routine hip exam should be performed, including:

- ROM

- strength and quality of contraction

- flexibility

- gait assessment

- lumbar spine and knee screen

The following are special tests for the acetabular labrum:

Impingement Test (Flexion-Adduction-Internal Rotation Test)[edit | edit source]

The hip impingement test is the most widely used and consistent physical exam procedure used to identify patients with a hip labral tear. The patient is placed in supine and the examiner passively flexes the hip to 90 degrees while performing adduction and internal rotation. According to Leiboid et al, the test is considered to have a positive finding if the patient experiences pain in the groin region. However, test positions and operational definitions of a positive test vary in literature. The Impingement test (Flexion-Adduction-Internal Rotation Test) has a sensitivity ranging from .95 to 1.00. [4][1]

Other modified versions of the Impingement test include the Impingement Provocation Test (Flexion-Adduction-Internal Rotation for antero-superior rim and Hyperextension-Abduction-External Rotation for the posterior-inferior rim) and the Flexion-Internal Rotation Test. Although these tests were found to have a sensitivity of 1.00, these studies did not specifically define a positive test or the location of pain upon testing. [4]

Fitzgerald Test[edit | edit source]

The Fitzgerald test utilizes 2 different test positions to determine if the patient has an anterior or posterior labral tear. To test for an anterior labral tears, the patient lies supine while the physical therapist (PT) performs flexion, external rotation, and full abduction of the hip, followed by extending the hip, internal rotation, and adduction. To test for posterior labral tear, the PT performs passively hip flexion, abduction, external rotation, followed by hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction while the patient is supine. Tests are considered to be positive with pain reproduction with or without an audible click. [4][2] The Fitzgerald test has a sensitivity of 1.00. [4]

Other tests[edit | edit source]

Other tests found to have high specificities but lacking high-quality study designs and supportive literature include the Flexion-Adduction-Axial Compression test and palpation to the greater trochanter. Flexion-Internal Rotation-Axial Compression test, Thomas test, Maximum Flexion-External Rotation Test, and Maximum Flexion-Internal Rotation Tests were found to have poor diagnostic measures. [4]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment for a diagnosis of an acetabular labral tear typically consists of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, limited weight-bearing, and physical therapy. During this time of limited activity, the patient’s pain may be reduced; however, the pain often reoccurs when the patient returns to normal activities. [2]

When conservative treatment does not resolve symptoms, surgical intervention isoften appropriate. The most common procedure is an excision or debridement of the torn tissue by joint arthroscopy. However, studies have demonstrated mixed post-surgical results. Fargo et al, found a significant correlation between outcomes and presence of arthritis on radiography. Only 21% of patients with detectable arthritis had good results from surgery, compared with 75% of patients without arthritis. Arthroscopic detection of chondromalacia was an even stronger indicator of poor long-term prognosis. [2]

Surgical treatment has been shown to have short-term improvements, however the long-term outcomes remain unknown. [2]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

The goal during PT management of an acetabular labral tear is to optimize the alignment of the hip joint and the precision of joint motion [2]. This can be done by

- Reducing anteriorly directed forces on the hip

- Addressing abnormal patterns of recruitment of muscles that control the hip [2].

- Instructing patients to avoid pivoting motions, especially under load, since the acetabulum rotates on a loaded femur, thus increasing force across the labrum [1].

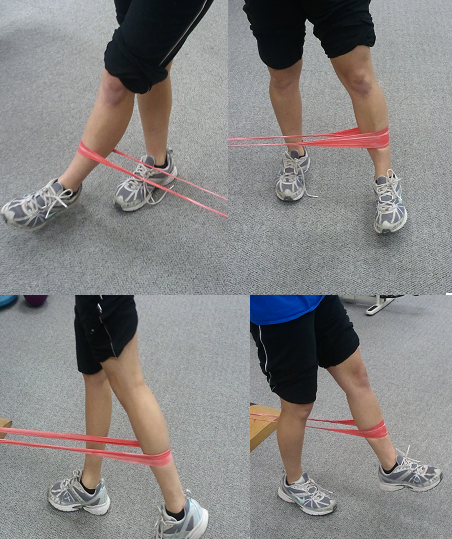

Because of abnormal recruitment patterns of the hip muscles in individuals with acetabular labral tears, PT treatment should optimize control of these muscles, specifically the hip adductors, deep external rotators, gluteus maximus, and iliopsoas muscles [2][5]. Additionally, if quadriceps femoris and hamstring muscles dominate, this should be corrected, as decreased force contribution from the iliopsoas during hip flexion and from the gluteal muscles during active hip extension results in greater anterior hip forces [6].

Through gait and foot motion analysis, the PT can discover any abnormalities, such as knee hyperextension causing hip hyperextension, walking with an externally rotated hip, or stiffness in the subtalar joint that need to be corrected through taping, orthotics, or strengthening [2].

Additionally, patients need to be educated regarding modification of functional activities to avoid any positions that cause pain, such as sitting with knees lower than hips or with legs crossed, getting up from a chair by rotating the pelvis on a loaded femur, hyperextending the hip while walking on a treadmill, etc.

After addressing abnormal movement patterns, focused muscle strengthening work and recovery of normal range of motion, patients eventually need to be progressed to advanced sensory-motor training and functional exercises, sport specific if applicable [5].

If surgery is performed, usually the first 6 weeks post-surgery are NWB or TTWB. Active and active assisted exercises are appropriate in gravity-minimized positions to maintain motion of the hip. Stationary bike, not recumbent bicycle, is appropriate; end range hip flexion should be done passively rather than actively. Rehabilitation protocols are currently based on surgeon and PT experience and can follow either labral debridement or repair guidelines, depending on the procedure performed, and move through 4 basic phases. The four basic phases follow the general progression of initial exercises, intermediate exercises, advanced exercises and sports specific training [7].

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Find a PT here.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Between a quarter and a half of all patients experiencing hip or groin pain are diagnosed with an acetabular labral tear; however this disorder is difficult to diagnose, and patients, on average, wait two years or longer before a diagnosis is made. [1] The options for treatment include both conservative (physical therapy) and non-conservative (surgery) approaches. PT can benefit patients by strengthening and re-educating neuromuscular control of the hip musculature, thus lending stability to the hip joint, while surgical excision or debridement of the torn labrum may be indicated for patients that do not reach desired outcomes conservatively.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed) [edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

<div class="researchbox"><rss>http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1XsgQGan4PZgSWV7lHuqOwoB3kVayOlxxIU5pMP5CwL_1jZck7%7Ccharset=UTF-8%7Cshort%7Cmax=10</rss></div>

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Groh MM, Herrera J. A comprehensive review of hip labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskeletal Med. 2009; 2:105 - 117.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Lewis C, Sahrmann S. Acetabular labral tears. Physical Therapy. 2006;86(1):110-121.

- ↑ Schmerl M, Pollard H, Hoskins W. Labral Injuries of the hip: a review of diagnosis and management. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(8):632

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Leiboid M, Huijbregts P, Jensen R. Concurrent Criterion-Related Validity of Physical Examination Tests for Hip Labral Lesions: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Manual &amp; Manipulative Therapy. [online]. 2008;16(2):E24-41.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Yazbek PM, Ovanessian V, Martin RL, Fukuda TY. Nonsurgical treatment of acetabular labrum tears: a case series. J of Ortho &amp;amp;amp;amp; Sports PT. 2011 May; 41(5): 346-353

- ↑ Lewis CL, Sahrmann SA, Moran DW. Effect of hip angle on anterior hip force during gait. Gait Posture. 2010 Oct; 32(4): 603-607

- ↑ Garrison JC, Osler MT, Singleton SB. Rehabilitation after arthroscopy of an acetabular labral tear. N Amer J of Sports PT. 2007 Nov; 2(4): 241-249