Glenoid Labrum

Original Editor - Priyanka Chugh

Top Contributors - Priyanka Chugh, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Wendy Snyders, Naomi O'Reilly, 127.0.0.1 and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

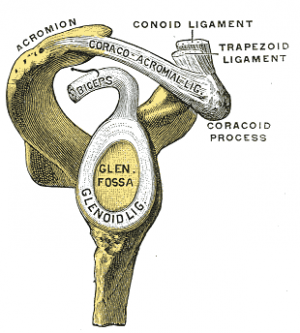

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous complex that attaches as a rim to the articular cartilage of the glenoid fossa. Its role is to deepen and increase the surface area of the glenoid (acting as a static stabiliser of the glenohumeral joint); resist anterior and posterior movement and assist with blocking shoulder dislocation and subluxation at the maximal ranges of motion.[1]

The labrum is frequently involved in shoulder pathology by acute trauma (e.g. shoulder dislocation) or more commonly by repeated microtrauma, e.g. shoulder subluxation.[2]

Structure[edit | edit source]

Glenoid labrum basics[1]:

- Made of fibrocartilage, 3 mm thick and 4 mm wide (highly variable).

- The labrum is most commonly triangular or round on cross-section.

- Inferior to the equatorial pole of the glenoid, the labrum gradually becomes rounder and smaller in contrast to superiorly , where it is more triangular in shape and larger.

Attachments[edit | edit source]

- Superiorly: tendon of the long head of biceps brachii[1]

- Anteriorly: superior glenohumeral ligament; middle glenohumeral ligament (variably)[1]

- Inferiorly: inferior glenohumeral ligament consisting of an anterior band, axillary pouch, and a posterior band[1]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with tears of the glenoid labrum present with an extensive range of non-specific symptoms including:

Anatomic Variants[edit | edit source]

- Inconsistent cross-sectional shape: blunted, cleaved, notched or flat.[1]

- Medialised posterior labrum[1]

- Anterior capsulolabral insertion variance[1]

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

The labrum's most important functions include[2]:

- Increasing the contact area between humeral head and scapula.

- Helping in the provision of the “viscoelastic piston” effect. This is particularly effective against traction traction stress.

- Providing insertion for stabilising structures, as a fibrous “crossroad”.

Accuracy of Assessment[edit | edit source]

The ability to predict the presence of a glenoid labral tear by physical examination was compared with that of magnetic resonance imaging (conventional and arthro gram) and confirmed with arthroscopy. The main points of study include[4]:

- 37 men and 17 women (average age, 34 years) in the study group, 64% were throwing athletes and 61% recalled specific traumatic events.

- Clinical assessment included history with specific attention to pain with overhead activities, clicking, and instances of shoulder instability.

- Physical examination included the apprehension, relocation, load and shift, inferior sulcus sign, and crank tests.

- Shoulder arthroscopy confirmed labral tears in 41 patients (76%).

- Magnetic resonance imaging produced a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 85%.

- Physical examination yielded a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 85%.

Conclusion: Physical examination is more accurate in predicting glenoid labral tears than magnetic resonance imaging. In this era of cost containment, completing the diagnostic workup in the clinic without expensive additional studies allows the patient's care to proceed in the most timely and economic fashion.

Location of Injuries[edit | edit source]

Labral injuries are named according to their location:

- Superior labrum: SLAP lesions are the most common and includes 8 types of SLAP tears. Less frequently, Andrew's lesion can occur[2].

- Anterior labral tear: This is very rare and is a pure anterior tear associated with a medial glenohumeral ligament tear[2].

- Posterior labrum: Less frequent when compared to anterior tears. It is caused by Walch’s internal impingement in the stable shoulder. There are various contributing factors including anterior capsule insufficiency, humeral retroversion or posteroinferior capsule contracture[2].

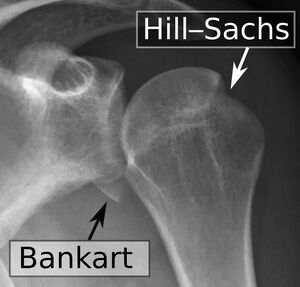

- Anteroinferior labrum: Typically found in shoulders with acute or chronic anterior instability. Injury types include: Bankart lesion; Perthes lesion; glenolabral articular disruption lesion (GLAD); anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion (ALPSA)[2].

- Posteroinferior labrum: These injuries are found in the rare cases of posterior instability. Injuries include reverse Bankart lesion; and Kim's lesion (superficial tears between the posterior glenoid labrum and glenoid articular cartilage without labral detachment)[2]. Other lesions include posterior GLAD and posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion (POLPSA).

- Circumferential labral lesion

Treatment and prognosis[edit | edit source]

No general rules exist for management of labral lesions are resected and others fixed. Labral repair or resection can be performed, possibly with capsuloplasty to address joint instability. The cause (which is usually shoulder instability), however, needs to be assessed and treated.[1] [2] See Shoulder Instability

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Radiopedia Glenoid Labrum Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/glenoid-labrum (accessed 10.1.2023)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Clavert P. Glenoid labrum pathology. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2015 Feb 1;101(1):S19-24.Available:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877056814003259 (accessed 10.1.2023)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sheikh, Y. (2021) Glenoid Labral tear: Radiology reference article, Radiopaedia Blog RSS. Available at: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/glenoid-labral-tear?lang=us (Accessed: 26 July 2023).

- ↑ Liu SH, Henry MH, Nuccion S, Shapiro MS, Dorey F. Diagnosis of glenoid labral tears: a comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examinations. The American journal of sports medicine. 1996 Mar;24(2):149-54